Chapter 76 Hypothermia

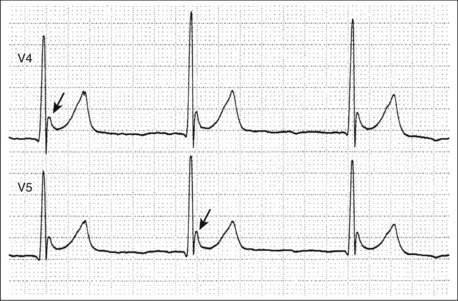

4 What is the J wave?

Also known as the Osborn wave, or hypothermic hump, the J wave is a hypothermia-related elevation of the J point at the junction of the QRS complex and ST segment (Fig. 76-1). J waves appear at temperatures at or below 32° C and are usually first seen in leads II and V6. As the temperature decreases further, they increase in size and may appear in the precordial leads. The J wave is neither specific, nor sensitive, nor prognostic in hypothermia. Automated electrocardiographic interpretation software may misinterpret the J wave as ischemic injury (ST elevation), and it is important not to fall into this trap.

7 You said mechanical agitation can cause arrhythmias. Is it acceptable to endotracheally intubate? What about central venous or pulmonary artery catheterization?

9 Aside from the life support measures described, what other initial management should be undertaken?

10 What are the methods for rewarming patients?

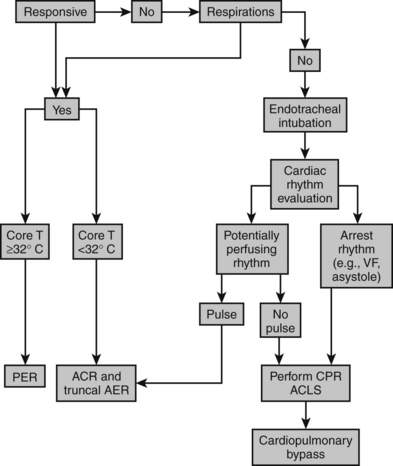

Because no controlled studies of various rewarming methods have been rigorously carried out, no rigid protocol can be justifiably instituted. Clinicians should be aware of their own institutional capacities. A recommended algorithm for rewarming is presented in Figure 76-2.

Figure 76-2 Algorithm for initial treatment and method of rewarming in accidental hypothermia. T, Temperature.

AER involves applying heat directly to the skin. There are a variety of methods for doing this, including forced air external rewarming, warm water immersion, heating pads, and radiant sources. AER is probably safe, though usually unnecessary in mild hypothermia. It has been associated with poor outcomes in moderate to severe hypothermia. Most of these problems have been attributed to peripheral vasodilation and resulting core temperature afterdrop with decreased overall rewarming rate. These effects may be mitigated by limiting AER to patients with brief hypothermic exposures (e.g., witnessed immersion), by restricting rewarming to the trunk, and by combining AER with ACR techniques listed next.

AER involves applying heat directly to the skin. There are a variety of methods for doing this, including forced air external rewarming, warm water immersion, heating pads, and radiant sources. AER is probably safe, though usually unnecessary in mild hypothermia. It has been associated with poor outcomes in moderate to severe hypothermia. Most of these problems have been attributed to peripheral vasodilation and resulting core temperature afterdrop with decreased overall rewarming rate. These effects may be mitigated by limiting AER to patients with brief hypothermic exposures (e.g., witnessed immersion), by restricting rewarming to the trunk, and by combining AER with ACR techniques listed next.

ACR includes airway rewarming by the administration of heated, humidified inhalant; administration of warmed intravenous fluids; and lavage of various body cavities (gastrointestinal tract, bladder, peritoneum, pleural cavities, mediastinum) with warm fluids. Airway rewarming and heated intravenous fluid administration are safe and simple. Temperatures from 40° to 45° C are appropriate for both. Irrigation techniques are less effective and invasive and have potentially serious technical complications. They should be avoided at centers where extracorporeal rewarming (ECR) techniques are available. Endovascular rewarming using systems designed for therapeutic hypothermia (see later) have recently been described for rewarming of accidental hypothermia victims. Diathermy is an ACR technique that can transmit heat to deep tissues via ultrasonic or microwave radiation, but clinical experience is limited.

ACR includes airway rewarming by the administration of heated, humidified inhalant; administration of warmed intravenous fluids; and lavage of various body cavities (gastrointestinal tract, bladder, peritoneum, pleural cavities, mediastinum) with warm fluids. Airway rewarming and heated intravenous fluid administration are safe and simple. Temperatures from 40° to 45° C are appropriate for both. Irrigation techniques are less effective and invasive and have potentially serious technical complications. They should be avoided at centers where extracorporeal rewarming (ECR) techniques are available. Endovascular rewarming using systems designed for therapeutic hypothermia (see later) have recently been described for rewarming of accidental hypothermia victims. Diathermy is an ACR technique that can transmit heat to deep tissues via ultrasonic or microwave radiation, but clinical experience is limited.

15 What should be done if a patient shivers during therapeutic hypothermia?

17 What are the important side effects of therapeutic hypothermia?

Key Points Hypothermia

1. Rigor mortis, dependent lividity, and fixed pupils do not reliably indicate death in severe hypothermia.

2. Endotracheal intubation is safe and has the same indications as in normothermia.

3. VF should be treated with standard ACLS in conjunction with rewarming, but multiple rounds of cardioversion and amiodarone should be avoided when the temperature is < 30° C.

4. CPR should be performed in patients with hypothermia without spontaneous circulation.

5. CPB should be initiated in patients with severe hypothermia without return of spontaneous circulation.

6. Therapeutic hypothermia (temperature = 30° C-34° C) is recommended for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest and is likely to be used for more conditions in the future.

1 Bernard S.A., Gray T.W., Buist M.D., et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:557–563.

2 Cohen J.A., Blackshear R.H., Gravenstein N., et al. Increased pulmonary artery perforating potential of pulmonary artery catheters during hypothermia. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1991;5:234–236.

3 Crawshaw L.I., Wallace H.L., Dasgupta S. Thermoregulation. In: Auerbach P.S., ed. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2007:110–124.

4 Danzl D.F. Accidental hypothermia. In: Auerbach P.S., ed. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2007:125–160.

5 Danzl D.F., Pozos R.S., Auerbach P.S., et al. Multicenter hypothermia survey. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:1042–1055.

6 Epstein E., Anna K. Accidental hypothermia. BMJ. 2006;332:706–709.

7 Gilbert M., Busund R., Skagseth A., et al. Resuscitation from accidental hypothermia of 13.7 degrees C with circulatory arrest. Lancet. 2000;355:375–376.

8 Goheen M.S.L., Ducharme M.B., Kenny G.P., et al. Efficacy of forced-air and inhalation rewarming using a human model for severe hypothermia. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1635–1640.

9 Graham C.A., McNaughton G.W., Wyatt J.P. The electrocardiogram in hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med. 2001;12:232–235.

10 Gregory J.S., Bergstein J.M., Aprahamian C., et al. Comparison of three methods of rewarming from hypothermia: advantages of extracorporeal blood warming. J Trauma. 1991;31:1247–1251.

11 Grissom C.K., Harmston C.H., McAlpine J.C., et al. Spontaneous endogenous core temperature rewarming after cooling due to snow burial. Wilderness Environ Med. 2010;21:229–235.

12 Holzer M. Targeted temperature management for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1256–1264.

13 Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest Study Group: Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:549–556.

14 Laniewicz M., Lyn-Kew K., Silbergleit R. Rapid endovascular warming for profound hypothermia. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:160–163.

15 Mattu A., Brady W.A., Perron A.D. Electrocardiographic manifestations of hypothermia. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:314–326.

16 Nunnally M.E., Jaeschke R., Bellingan G.J., et al. Targeted temperature management in critical care: a report and recommendations from five professional societies. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1113–1125.

17 Pitoni S., Sinclair H.L., Andrews P.J. Aspects of thermoregulation physiology. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:115–121.

18 Polderman K.H. Mechanisms of action, physiological effects, and complications of hypothermia. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(7 Suppl):S186–S202.

19 Polderman K.H., Herold I. Therapeutic hypothermia and controlled normothermia in the intensive care unit: practical considerations, side effects, and cooling methods. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1101–1120.

20 Tømte Ø., Drægni T., Mangschau A., et al. A comparison of intravascular and surface cooling techniques in comatose cardiac arrest survivors. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:443–449.

21 Vanden Hoek T.L., Morrison L.J., Shuster M., et al. Part 12: Cardiac arrest in special situations: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S829–S861.

22 Walpoth B.H., Walpoth-Aslan B.N., Mattle H.P., et al. Outcome of survivors of accidental deep hypothermia and circulatory arrest treated with extracorporeal blood warming. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1500–1505.