Hypospadias

Chordee, which is ventral curvature of the penis, has an inconsistent association with hypospadias. The degree of chordee is ultimately more significant in the surgical treatment of hypospadias than is the initial location of the meatus. A subcoronal hypospadias with little or no chordee is much less complicated to repair than is one with significant chordee and insufficient ventral skin. For this reason, when discussing the degrees of hypospadias, it is more appropriate to use the clinically relevant and common classification system that refers to the meatal location after the chordee has been released (Box 59-1).1

Embryology

Normal phallic development occurs in weeks 7 to 14 of gestation. By 6 weeks of gestation, the genital tubercle is formed anterior to the urogenital sinus. In the next week, two genital folds form caudad to the tubercle and a urethral plate develops between them. Under the influence of testosterone from the fetal testes, which begins to be produced at about 8 weeks of gestation, the inner genital folds fuse medially to create a tube that communicates with the urogenital sinus and runs distally to end at the base of the glans. The formation of the penile urethra is thus generally completed by the end of the first trimester.2

Classically, the glanular urethra is thought to form as an ectodermal ingrowth on the glans. This ingrowth deepens to meet the distal urethra that has formed from the closure of the endodermal genital folds. The capacious junction of these two structures is the fossa navicularis.3 Recently, this theory has been challenged by the endodermal ingrowth theory. It suggests that the entire urethra forms from the urogenital sinus, which is endoderm. This endoderm differentiates into stratified squamous epithelium.4 The formation of the glanular urethra is the last step in the formation of the completed urethra. This sequence probably accounts for the predominance of glanular and coronal hypospadias.

Historical Perspective

The first description of hypospadias and its operative correction was reported in the 1st and 2nd centuries by the Alexandrian surgeons Heliodorus and Antyllus. They described the defect of hypospadias and its relation to problems with urination and ineffective coitus. They further described a surgical treatment consisting of amputation of the glans distal to the hypospadiac meatus.5,6

Little progress was made in the surgical treatment of hypospadias until the 19th century, when two Americans, Mettauer and Bush, described using a trocar to establish a channel from the meatus to the glans. Dieffenbach also described a similar technique in the 1830s. None of these methods was very successful.5

In 1874, Theophile Anger reported the successful repair of a penoscrotal hypospadias using the technique described in 1869 by Thiersch for the repair of epispadias in which lateral skin flaps were tubularized to form the neourethra. Anger’s report initiated the modern era of hypospadias surgery characterized by the use of local skin flaps.7,8 Duplay soon described his two-stage technique.6 In the first stage, the chordee was released; in the second stage, a ventral midline strip of skin was covered by closure of the lateral penile skin flaps in the midline. Duplay did not believe that it was necessary to form the urethral tube completely because he thought that epithelialization would occur even if an incomplete tube was buried under the lateral skin flaps. Browne used this concept in his well-known ‘buried strip’ technique, which was widely used in the early 1950s.9

In the late 1800s, various surgeons reported on penile, scrotal, and preputial flap techniques for multistage procedures. Several of them used the technique of burying the penis in the scrotum to obtain skin coverage, similar to the technique described by Cecil and Cuip in the late 1950s.10 In 1913, Edmonds was the first to describe the transfer of preputial skin to the ventrum of the penis at the time of release of chordee. At a second stage, the Duplay tube was created to complete the urethral closure. Byars popularized this two-stage technique in the early 1950s.11 Smith further improved the outcomes by denuding the epithelium of one of the lateral skin flaps to give a ‘pants-over-vest’ closure to reduce the risk of fistula formation.12 Belt devised another preputial transfer, two-stage procedure that was popularized by Fuqua in the 1960s.13

Nove-Josserand, in 1897, was the first to report the use of a free, split-thickness skin graft in an attempt to repair hypospadias.14 Over the next 20 years, various other tissues were used as free grafts, including saphenous vein, ureter, and appendix, with varying success. McCormack used a free, full-thickness skin graft in a two-stage repair.15 In 1941, Humby described a one-stage approach using the full thickness of the foreskin.16 Devine and Horton later popularized this free preputial graft technique with very good results.17

In 1947, Memmelaar described the use of bladder mucosa as a free graft technique in a one-stage repair.18 In 1955, Marshall and Spellman used bladder mucosa in a two-stage technique.19 Urologists in China also experienced good success with a primary repair using bladder mucosa. This technique was developed independently during the period of scientific and cultural isolation in China.20 Buccal mucosa from the lip was employed for urethral reconstruction in 1941 by Humby16 and has recently gained renewed attention as a free graft technique.21

Improvement in preputial and meatal-based vascularized flaps over the last 30 to 40 years have greatly advanced hypospadias repair. Through contributions of surgeons such as Mathieu, Barcat,1 Mustardé,22 Broadbent,23 Hodgson,24 Horton and Devine,17 Standoli,25 and Duckett,26 the single-stage repair of even the most severe forms of hypospadias has become commonplace.

Clinical Aspects

Incidence

The incidence of hypospadias has been estimated between 0.8 and 8.2 per 1,000 live male births.27 The wide variation probably represents some geographic and racial differences, but of more significance is the exclusion of the more minor degrees of hypospadias in some reports. If all degrees of hypospadias, even the most minor, are included, then the incidence is probably 1 in 125 live male births.28 With the most quoted figure of 1 per 250 live male births, it can be assumed that more than 6,000 boys are born with hypospadias each year in the USA.29

Etiology

A defect in the androgen stimulation of the developing penis, which precludes complete formation of the urethra and its surrounding structures, is the ultimate cause of hypospadias. This defect can occur from deficient androgen production by the testes and placenta, from failure of testosterone to convert to dihydrotestosterone by the 5α-reductase enzyme, or from deficient androgen receptors in the penis. Various disorders of sexual differentiation (DSD) can cause deficiencies at any point along the androgen-stimulation axis. These are discussed in Chapter 62.

The origin of hypospadias not associated with DSD is unclear. An endocrine cause has been implicated in some reports that show a diminished response to human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in some patients with hypospadias, suggesting delayed maturation of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis.30,31 Other reports have described an increased incidence of hypospadias in monozygotic twins, suggesting an insufficient amount of hCG production by the single placenta to accommodate the two male fetuses.32

Environmental causes also have been implicated. A higher incidence of hypospadias has been noted in winter conceptions.32 A weak association between hypospadias and the maternal ingestion of progestin-like agents has also been noted.33,34 No association has been found between hypospadias and oral contraceptive use before or during early pregnancy.35

Genetic factors in the etiology of hypospadias are implicated by the higher incidence of this anomaly in first-degree relatives of hypospadiac patients.27,34,36 In one study that evaluated 307 families, the risk of hypospadias in a second male sibling was 12%. If the index child and his father were affected, the risk for a second sibling increased to 26%. If the index child and a second-degree relative (rather than the father) were affected, the risk of the sibling being affected was only 19%.36 This pattern suggests a multifactorial mode of inheritance, with these families having a higher than average number of influential genes for creation of hypospadias.36 A combination of the endocrine, environmental, and genetic factors likely determines the potential for developing the hypospadias complex in any one individual.31,32

Anatomy of the Defect

The clinical significance of hypospadias is related to several factors. The abnormal location of the meatus and the tendency toward meatal stenosis result in a ventrally deflected and splayed stream. This fact makes the stream difficult to control and often makes it difficult for the patient to void while standing. The ventral curvature associated with chordee can lead to painful erections, especially with severe chordee. Impaired copulation and thus inadequate insemination is a further consequence of significant chordee. In addition, the unusual cosmetic appearance associated with the hooded foreskin, flattened glans, and ventral skin deficiency frequently has an adverse effect on the psychosexual development of the adolescent with hypospadias.37–41 All of these factors are evidence that early surgical correction should be offered to all boys with hypospadias, regardless of the severity of the defect.

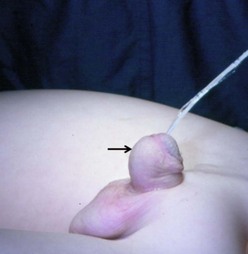

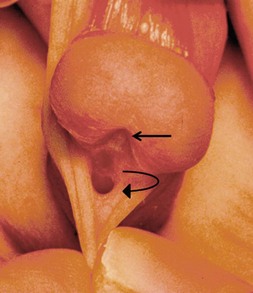

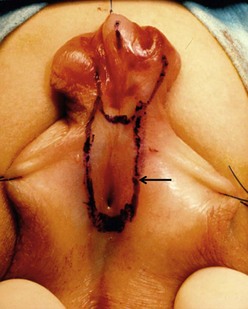

The distal form of hypospadias is the most common (see Box 59-1). Frequently, little or no associated chordee is present (Fig. 59-1). The size of the meatus and the quality of the surrounding supportive tissue as well as the configuration of the glans are variable, and ultimately determine the appropriate operative technique. Well-formed, mobile perimeatal skin and a deep ventral glans groove may allow development of perimeatal flaps to create the urethra (Fig. 59-2). In contrast, atrophic and immobile skin around the meatus may require tissue transfer from the preputium to form the neourethra.

FIGURE 59-1 Distal hypospadias with a stenotic meatus (arrow) located on the glans with no chordee. This patient is a good candidate for a meatal advancement and glanuloplasty (MAGPI) procedure or a tubularized incised urethral plate (TIP) operation.

FIGURE 59-2 Patulous, subcoronal meatus (curved arrow) with mobile perimeatal skin and deep ventral glans groove (straight arrow). This is a good variant for a meatal-based flap procedure, glans approximation (GAP), or tubularized incised urethral plate (TIP) repair.

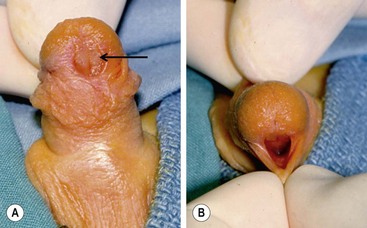

An unusual variant of the distal hypospadias is the large wide-mouthed meatus with a circumferential foreskin (the megameatus/intact prepuce variant) (Fig. 59-3).42 Owing to the intact prepuce, this variant is often not identified until a circumcision has been performed. If clinicians discover hypospadias during circumcision, they should stop and preserve the foreskin, even if the dorsal slit has been created.

FIGURE 59-3 (A) Previously circumcised penis with megameatus (arrow) and intact circumferential prepuce. (B) Large wide-mouthed meatus in the same penis as shown in (A).

At times, the distally located meatus may be associated with significant chordee, sometimes of a severe degree (Fig. 59-4). The release of the chordee places the meatus in a much more proximal location, requiring more complicated transfers of tissue to bridge the gap between the proximal meatus and the tip of the glans.

FIGURE 59-4 Scrotal hypospadias with severe chordee and marked penoscrotal transposition is seen in this infant.

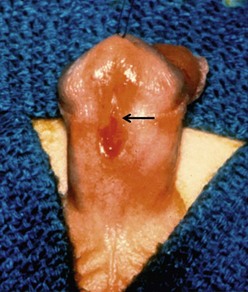

When the meatus is located on the penile shaft, the character of the urethral plate (midline ventral shaft skin distal to the meatus) is important in determining what type of repair is possible. A well-developed and elastic urethral plate suggests minimal, if any, distal ventral curvature (Fig. 59-5). However, a thin atrophic urethral plate heralds a significant chordee. The proximal supportive tissue of the urethra also is important. If there is a lack of spongiosum proximal to the hypospadiac meatus, this portion of the native urethra is not substantial enough to use in the repair (Fig. 59-6). Therefore, the neourethra must be constructed from the point of adequate spongiosum.

FIGURE 59-5 Midshaft hypospadias with elastic, well-developed urethral plate distal to the meatus (arrow). No significant chordee is present. This is a good variant for an onlay island flap procedure or possibly a tubularized incised urethral plate operation.

FIGURE 59-6 Midshaft hypospadias with a lack of spongiosum support proximal to the meatus. The urethra should be opened back to an area of good spongiosum support at the penoscrotal junction.

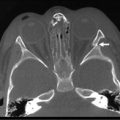

The position of the meatus at the penoscrotal, scrotal, or perineal location is usually associated with severe chordee, which requires chordee release and an extensive urethroplasty (Fig. 59-7). This type is usually more predictable in the preoperative period as to the choice of technique than are some of the more distal types previously discussed.

Associated Anomalies

Inguinal hernia and undescended testes are the most common anomalies associated with hypospadias. They occur in 7–13% of patients with a greater incidence when the meatus is more proximal.43–45 An enlarged prostatic utricle also is more common in posterior hypospadias, with an incidence of about 11%.44 Infection is the most common complication of a utricle, but surgical excision is rarely necessary.46 Several reports have emphasized significantly high numbers of upper urinary tract anomalies associated with hypospadias,47–50 suggesting that routine upper tract screening is necessary. However, when the association is studied selectively, it is evident that the types of hypospadias at risk for significant upper tract anomalies are the penoscrotal and perineal forms, and those associated with other organ system abnormalities.43,45 When one, two, or three other organ system abnormalities also occur, the incidence of significant upper tract anomalies is 7%, 13%, and 37%, respectively. Associated myelomeningocele and imperforate anus carry a 33% and 46% incidence, respectively, of upper urinary tract malformations. In isolated posterior hypospadias, the incidence of associated upper tract anomalies is 5%.45

In middle and distal hypospadias, when not associated with other organ system anomalies, the incidence is similar to that in the general population.43,45,51 Therefore, it is recommended that screening for upper urinary tract abnormalities by voiding cystourethrogram and renal ultrasonography be performed in patients with penoscrotal and perineal forms of hypospadias, and in those with anomalies associated with at least one additional organ system. Screening should also be done in patients with other known indications, such as a history of urinary tract infection, upper or lower tract obstructive symptoms, hematuria, and in those boys having a strong family history of urinary tract abnormalities.52

DSD are also potentially associated with hypospadias. This association is rare in the routine forms of hypospadias. Failure of testicular descent, micropenis, penoscrotal transposition (see Fig. 59-4), or bifid scrotum (see Fig. 59-7) when associated with hypospadias, are all signs of potential DSD and warrant evaluation with karyotype screening.27,53,54

Treatment

Age at Repair

The technical advances over the past few decades have made it possible to repair hypospadias in the first 6 months of life in most patients.55–57 Some surgeons have suggested delaying repair until after the child is age 2 years.52,58–60 However, most surgeons who deal routinely with hypospadias prefer to perform the repair when the patient is 6 to 12 months old.53,54,56,57,61,62 One study compared the emotional, psychosexual, cognitive, and operative risks for hypospadias. The ‘optimal window’ recommended for repair was age 6 to 15 months.63 There is also evidence that healing may be better with decreased inflammatory factors and less scarring in the less than 6 month age group.62 Unless other health or social problems require delay, we believe the ideal time to complete penile reconstruction in the pediatric patient is about age 5 to 6 months.64 The anesthetic risk is low and, at this age, postoperative care is much easier for the parents than it is when the child is a toddler.

Objectives of Repair

The objectives of hypospadias correction are divided into the following categories:

1. Complete straightening of the penis

2. Locating the meatus at the tip of the glans

3. Forming a symmetric, conically shaped glans

If these objectives can all be attained, the ultimate goal of forming a ‘normal’ penis for the child with hypospadias can be accomplished.

Straightening

Curvature of the penis is difficult to judge, at times, in the preoperative period. Artificial erection, by injecting physiologic saline in the corpora at the time of operation allows determination of the exact degree of curvature.65 This curvature may be caused only by ventral skin or subcutaneous tissue tethering, which is corrected with the release of the skin and dartos layer.66,67 Infrequently, the curvature may be secondary to true fibrous chordee, which requires division of the urethral plate and excision of the fibrous tissue down to the tunica albuginea.

Sometimes, even after extensive ventral dissection of chordee tissue, a repeated artificial erection still reveals the presence of significant ventral curvature. This finding is usually secondary to the uncommon problem of corporal body disproportion which is caused by a true deficiency of ventral corporal development. This problem can be corrected by making a releasing incision in the ventral tunica albuginea and inserting either a dermal or a tunica vaginalis patch to expand the deficient ventral surface.68,69 Others have suggested the use of small intestinal submucosa as an off-the-shelf substitute for the autologous grafts.70 Another technique is to excise wedges of tunica albuginea dorsally with transverse closure to shorten this dorsal surface and straighten the penis.71,72 Other surgeons have had success with dorsal plication without excision of tunica albuginea.73,74 Anatomic studies suggest that this plication should be done in the midline dorsally.75 Still others advocate corporal rotation dorsally with or without penile disassembly to correct severe chordee.76,77

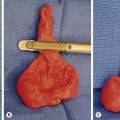

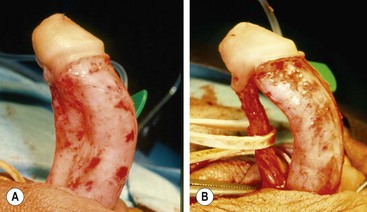

Axial rotation of the penis, or penile torsion, is another aspect of penis straightening that must be managed. This problem can generally be corrected by releasing the dartos layer as far proximal as possible on the penile shaft. This allows the ventral shaft to rotate back to the midline and corrects the torsion. Chordee or torsion can also occur without hypospadias (Fig. 59-8). The management of these boys encompasses the same spectrum of approaches as for hypospadias.78,79

FIGURE 59-8 (A) Chordee without hypospadias. The meatus is located at the tip of the glans with marked ventral curvature. (B) Fibrous ventral tissue is all released. The urethra is mobilized, but curvature persists, indicating corporeal body disproportion. This requires a ventral patch or dorsal plication (see text).

Locating the Meatus

In glanular and subcoronal variants, the configuration of the meatus is the factor that determines what technique is used to move the meatus distally on the glans. Meatoplasty with or without dorsal advancement, distal urethral mobilization and tubularization, or meatal-based flaps are the methods selected in most cases of distal hypospadias.80,81 In the more proximal forms, creating the neourethra with local vascularized skin flaps or free grafts allows positioning the urethra at the end of the penis. Alternatively, glans channeling or glans splitting allows creation of the meatus at the tip of the glans.1,17,22,26,82,83

Urethral Construction

Formation of the neourethra can be accomplished with local skin flaps, various types of free grafts, or vascularized pedicle flaps. Local skin flaps can be formed from in situ skin or dorsal skin transferred to the ventrum in a previous stage. In either case, it is important to avoid making these flaps too narrow or thin because their vascular supply can be compromised. The hypospadiac urethral plate has been shown in histologic studies to consist of epithelium covering well-vascularized connective tissue without fibrosis.84 This information supports the clinical findings that urethral plate preservation is helpful for successful urethroplasty. Free grafts depend on an adequately vascularized bed for survival. Therefore, they should not be placed in a scarred channel. Well-vascularized subcutaneous tissue and skin must cover them to allow adequate neovascularization and survival of the graft.17

Mobilized vascularized flaps of preputium have a more reliable blood supply than do free grafts. Therefore, if they are available, these flaps are the choice of most surgeons.24,26,83,85 They may be used as patches onto a strip of native urethral plate to complete the urethra, or they may be tubularized and used as bridges over the gap between a proximal native urethra and the end of the glans.26,86 A watertight closure of the well-vascularized neourethra is formed, with care being taken to make it uniform in caliber and of appropriate size for the age of the child. This closure helps avoid stricture and the formation of saccules, diverticula, and fistulas.

Cosmesis

Buttonholes of the dorsal skin allow the penis to come through this defect, draping the distal preputium over the ventral surface of the penis.19 This maneuver has the advantage of transferring well-vascularized skin over the repair, but it is not as appealing cosmetically.

A more satisfactory method of transferring skin to the ventrum is splitting the dorsal skin in the midline longitudinally and advancing the flaps around on either side to meet in the ventral midline. This technique allows a midline ventral closure, which simulates the median raphe. Moreover, it allows a subcoronal closure to the preputial skin circumferentially, which simulates the suture lines of a standard circumcision.87,88 Another adjunct is to advance lateral flaps of inner preputial skin from each side to the ventral midline of the penis at the time of glansplasty or closure of glans wings.89 Approximating these flaps in the midline gives the appearance of an intact circumferential preputial collar, further enhancing the potential for an anatomically normal skin closure (see Fig. 59-13).

Some patients, particularly those in European countries, prefer the appearance of a noncircumcised penis. In distal repairs, reconstruction of the preputium for a noncircumcised appearance can be accomplished in select cases.90 Correction of the more significant degrees of penoscrotal transposition is often necessary to avoid the feminizing appearance. In some cases, this step can be done at the time of the original repair. However, when using vascularized pedicle flaps for the repair, it is usually safer to correct significant penoscrotal transposition with rotational flaps at a later time.91–94

Operative Approaches

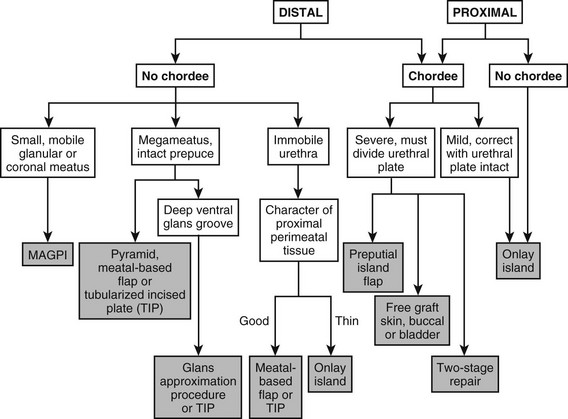

Due to the wide variation in the anatomic presentation of hypospadias, no single urethroplasty is applicable for every patient. At times, a final decision regarding the degree of curvature and the ultimate location of the meatus cannot be made until the operation has started and an artificial erection is performed. The surgeon who repairs hypospadias must be adaptable and experienced to deal with all variants of the defect. Versatility and experience with all options of surgical treatment are the keys to successful management. By recognizing the sometimes subtle nuances of meatal variation, glans configuration, and curvature character, the experienced surgeon can choose the optimal technique (Fig. 59-9).

FIGURE 59-9 Flow diagram for types of repair in variants of hypospadias. MAGPI, meatal advancement and glansplasty. TIP, tubularized incised plate urethroplasty.

Anterior Variants

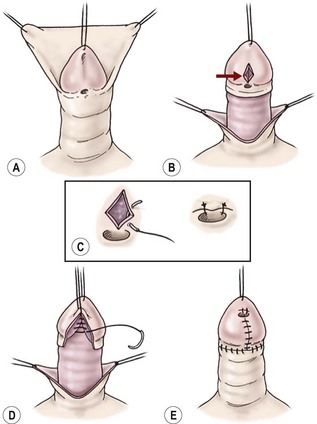

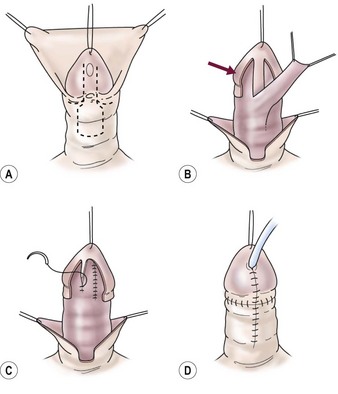

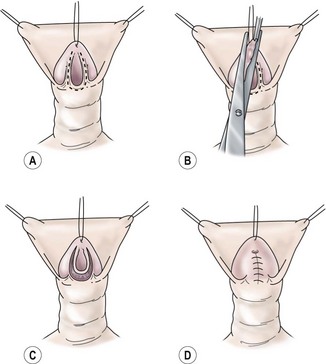

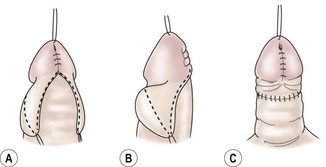

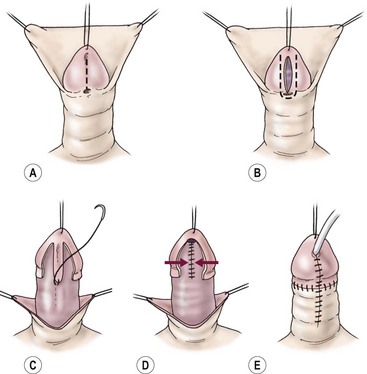

Some glanular variants are amenable to the meatal advancement and glansplasty (MAGPI) repair (Fig. 59-10).95 A stenotic meatus with good mobility of the urethra and a fairly shallow ventral glanular groove are the anatomic characteristics best suited for the MAGPI. A wide-mouthed meatus is not amenable to the MAGPI repair. The meatal-based flap repair may be used effectively in this situation, assuming no chordee is present and mobile, well-vascularized skin exists proximal to the meatus (Fig. 59-11).96,97 This repair works well when there is a moderately deep ventral groove, allowing the urethra to be placed deep in the glans and a conically shaped glans to be created after closure of the glans wings. The glans approximation procedure is useful when a wide-mouthed proximal glanular meatus exists with a very deep groove (Figs 59-12 and 59-13).98 The pyramid procedure is well suited for the fish-mouth type of meatus seen in the megameatus/intact prepuce variant.42 These repairs give a very good cosmetic result when performed in the proper situation.

FIGURE 59-10 Meatal advancement and glansplasty. (A) Circumferential subcoronal incision to deglove the penile shaft skin. (B) Longitudinal incision through the ventral groove of glans (arrow). (C) Transverse closure of glans groove incision to advance dorsal urethral plate and to open stenotic meatus. (D) Glans tissue approximated ventrally in the midline to restore conical configuration to glans. (E) Completion of the skin closure.

FIGURE 59-11 Meatal-based flap repair. (A) Parallel incisions along ventral groove distal to the meatus and formation of meatal-based flap proximal to meatus. (B) Glans wings developed on either side of the urethral plate (arrow) to close over the neourethra later. Meatal-based flap is mobilized distally maintaining good vascular and tissue support. (C) Flap is anastomosed to bilateral edges of the urethral plate to form neourethra. (D) Glans wings are closed over the neourethra in the midline, giving conical glans configuration. Penile shaft is covered with dorsal foreskin advanced ventrally.

FIGURE 59-12 Glans approximation procedure. (A) Deep ventral groove and patulous, coronal meatus with outline of proposed incision. (B) Skin is excised along previously marked U-shaped line. (C) De-epithelialized glans with the urethral plate intact. (D) Two-layer closure of the glanular urethra with glans skin still open. (From Zaontz MR. The GAP [glans approximation procedure] for glandular/coronal hypospadias. J Urol 1989;141:359–61.)

FIGURE 59-13 (A) Glanular skin approximated and lateral wings of inner preputial skin outlined. (B) Lateral view of outline for preputial collar. (C) Lateral preputial wings closed in midline to give circumferential preputial collar. (From Zaontz MR. The GAP [glans approximation procedure] for glanular/coronal hypospadias. J Urol 1989;141:359–61.)

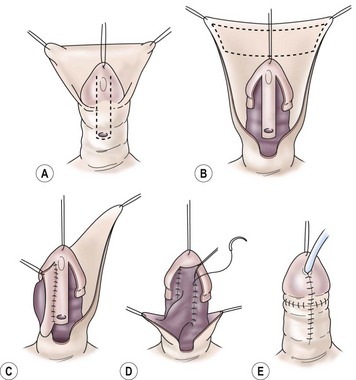

The tubularized incised plate urethroplasty (TIP) is a modification of the Thiersch–Duplay tubularization, which involves a deep longitudinal incision of the urethral plate in the midline (Fig. 59-14). This allows the lateral skin flaps to be mobilized and closed in the midline without tension. This procedure also allows repair of the wide-mouthed meatus variant with a flat, shallow ventral groove without the need for additional flaps.99 The TIP urethroplasty has gained wide acceptance in the last 20 years. Its durability and long-term success have been demonstrated even in the more proximal variants.100–102

FIGURE 59-14 Tubularized incised urethral plate (TIP) technique. (A) Urethral plate is incised longitudinally. (B) Glans incisions are made longitudinally, wide enough to leave two strips of epithelium for 10 French size neourethra. (C) Neourethra is tubularized in the midline with multiple layers and dartos flap to reinforce. (D) Glans wings are closed in the midline. (E) Skin closure is completed and the urethral stent is placed (optional).

Middle Variants

The amount of ventral curvature generally dictates the type of repair in middle- and distal-shaft hypospadias. When no significant chordee is present, the TIP repair can frequently be performed. Another approach is the onlay island flap technique (Fig. 59-15).86 This procedure involves mobilizing an inner preputial flap on its pedicle and rotating it ventrally to lay on the well-developed ventral urethral plate to complete the tubularization of the neourethra. This technique is applicable to many forms of penile shaft hypospadias.

FIGURE 59-15 Onlay island flap repair. (A) Outline of incisions along the well-developed urethral plate with no chordee. (B) Mobilization of glans wings and shaft skin with urethral plate intact distal to meatus. Outline of inner preputial island flap that will be transposed ventrally for onlay completion of neourethra. (C) Island flap transposed ventrally on pedicle. The first part of the anastomosis is completed. (D) Remainder of anastomosis to complete neourethra to tip of glans. (E) Glans wings are approximated over the neourethra in the ventral midline. The penile shaft is covered with the ventral advancement of dorsal foreskin.

In milder degrees of chordee, the curvature can be corrected without dividing the urethral plate by incising tethering bands lateral to the urethral plate or by dorsal plication techniques.74,75 This allows either the onlay island flap technique or TIP to be used instead of the tubularized pedicle flap or free graft, which have a higher incidence of complications.54 If significant chordee is present, division of the urethral plate may be necessary. This moves the meatus more proximal and requires treatment as described for proximal variants.

Proximal Variants

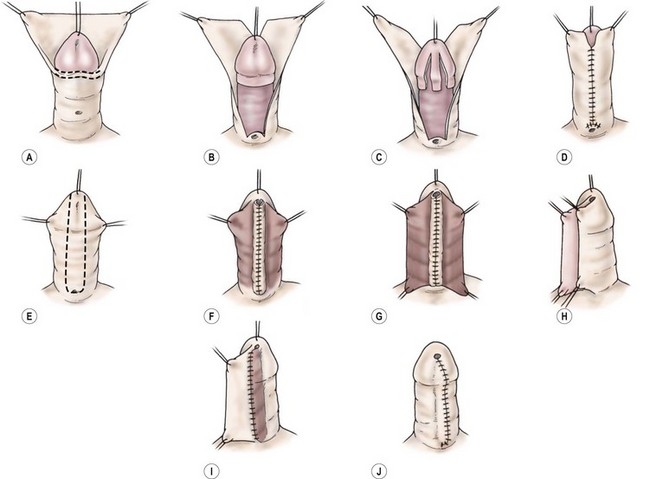

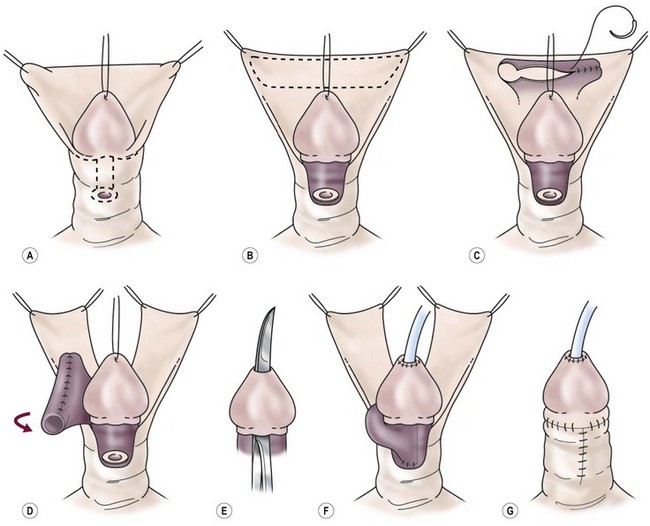

Many of the scrotal and perineal forms of hypospadias are associated with significant chordee, which requires division of the urethral plate, and results in a gap between the proximal native urethra and the tip of the glans. This gap can be corrected during staged procedures in which coverage of the ventral penile shaft is attained by rotation of dorsal flaps to the ventrum, with later tubularization to form the neourethra (Fig. 59-16).

FIGURE 59-16 Two-stage Durham Smith repair. (A) Release of chordee. (B) Splitting of dorsal preputium. (C) Denuded ventral glans before transposing preputial skin to ventrum. (D) Transposition of dorsal foreskin to ventrum completes the first stage. (E) U-shaped incision around the meatus and out onto glans. (F) Tubularization of Duplay-type tube to form the neourethra. (G) Second layer of soft tissue to reinforce suture line. (H–J) Overlapping skin closure with de-epithelialization of inner flap gives a ‘double-breasted’ closure of the skin. (Redrawn from Belman AB. Urethra. In: Kelalis PP, King LR, Belman AB, editors. Clinical Pediatric Urology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1985.)

Another method is the tubularized free graft anastomosed to the native urethra proximally and extended to the end of the glans by a tunneling or splitting technique. The most commonly used free grafts are full-thickness skin, bladder mucosa, or buccal mucosa. Preputial skin is much preferred to extragenital skin.17,103 If genital skin is not available, buccal mucosa may be the next best tissue.21,104,105 Vascularized flaps are a more physiologically sound alternative to free grafts. The transverse inner preputial island flap that is tubularized and transposed ventrally to form the neourethra is the preferred vascularized flap (Fig. 59-17).106 In contrast to free grafts, it provides good preputial skin with a reliable blood supply that does not rely on neovascularization for healing of the neourethra. Occasionally, the length of the prepuce alone may not be adequate to bridge the defect to a very proximal meatus. In this case, the shiny nonhair-bearing skin around the meatus can be tubularized (Fig. 59-18), moving the proximal urethra to the penoscrotal junction. The preputial vascularized tube graft can then be used to bridge the remaining distance to the end of the penis.53

FIGURE 59-17 Transverse preputial island flap tube repair. (A) Release of chordee and degloving of penile shaft skin. (B) Outline of inner preputial island flap. (C) Tubularization of inner preputial island flap. (D) Transposition of the tubularized island flap to the ventrum, maintaining pedicle blood supply. (E) Creation of a channel through glans tissue with sharp incisional and excisional technique. (F) Island tube anastomosed to proximal native urethra, brought through glans channel and anastomosed to epithelium at tip of glans. (G) Penile shaft covered with dorsal foreskin advanced ventrally. Skin closure is completed.

FIGURE 59-18 Outline of nonhair-bearing skin distal to scrotal meatus (arrow) that will be tubularized to move the meatus to the penoscrotal junction. Island flap tube will complete the repair to the end of the glans.

In some cases, the penile shaft may be deficient enough to cause concern about ventral coverage after formation of the neourethra. The double-face island flap can solve this problem.24 This technique leaves some of the outer preputial skin attached to the pedicle after tubularizing the inner preputial layer. This outer preputium is transferred to the ventrum with the pedicle and supplies skin coverage to the ventral shaft. However, the complications associated with the double-face island flap are numerous, and it has few advocates.55

The author prefers the transverse island flap in a one-stage procedure in most cases of proximal hypospadias with chordee.106 In the rare case in which the skin deficiency is so severe that a vascularized pedicle cannot be used or in which the chordee is so severe that a dermal or tunica vaginalis graft is required to correct disproportion, a two-stage repair may be better.107–109

Technical Perspectives

Optical Magnification

Most surgeons agree that optical magnification is indispensable in hypospadias surgery. Standard operating loupes, ranging from 2.5× power to 4.5×, are generally thought to be ideal for the magnification needed for this type of surgery. Some surgeons advocate the use of the operating microscope and suggest an improved outcome.110 However, most surgeons do not believe this degree of magnification is necessary. The microscope may be overly cumbersome for the small improvement in visualization it may provide.111

Sutures and Instruments

Fine absorbable suture is used by most surgeons to close the neourethra. Polyglycolic or polyglactin material is probably the most common suture choice. Some surgeons prefer the longer-lasting polydioxanone suture, but increased rates of stricture have been reported.110,112 Permanent sutures of nylon or polypropylene, in a continuous stitch that is pulled out 10 to 14 days after surgery, are favored by some surgeons.12,56

Urinary Diversion

The goal of the surgeon in any urinary diversion procedure in hypospadias repair is to protect the neourethra from the urinary stream during the initial healing phase. In theory, this diversion should decrease the complication rate, particularly fistula formation. The more traditional perineal urethrostomy and suprapubic cystostomy are uncomfortable and cumbersome to manage in the postoperative period. Small indwelling 6-8 French polymeric silicone (Silastic) tubes left through the repair and into the bladder allow drainage of the urine into the diaper in infants (Fig. 59-19).111 This technique greatly facilitates the outpatient care of these patients. These stents are well tolerated by the babies. Problems with the stents becoming plugged or dislodged are uncommon.

FIGURE 59-19 Occlusive dressing of transparent adhesive material in sandwich fashion on the abdominal wall, with a 6 French soft polymeric silicone (Silastic) indwelling tube inserted for bladder drainage.

Some surgeons favor a stent that traverses the repair but is not indwelling in the bladder.110 The patient is allowed to void, but the stent protects the repair. The author prefers the indwelling bladder stent, left for 5 to 14 days, depending on the complexity of the repair. In older children who will not tolerate wearing a diaper, a 6 to 8 French Foley catheter may be used in the simpler distal repairs and a suprapubic cystostomy can be performed in the more complex repairs. Suprapubic drainage should be used in complex reoperations or in any repairs requiring a free graft. Studies have suggested that diversion is not required for simpler distal procedures, such as MAGPI, meatal-based flap, or distal Duplay tubes. Straightforward repairs of small fistulas can also be accomplished without diversion.112–114

Dressings

Hypospadias dressings should apply enough gentle pressure on the penis to help with hemostasis and to decrease edema, without compromising the vascularity of the repair. Various dressings accomplish this purpose. Common dressings include transparent adhesive dressings wrapped around the penis or fixed to the abdominal wall in a sandwich-like fashion (see Fig. 59-19). A DuoDerm (ConvaTec, Skillman, NJ) dressing can be applied around the penis as an alternative to using a transparent adhesive dressing.110 Two prospective studies have shown that the type of dressing does not influence healing or complication rates.115,116 I have continued to use a transparent dressing against the abdominal wall for its hemostatic effect in the first 12-24 postoperative hours.

Analgesia

Postoperative pain is generally controlled with oral analgesics. Bladder spasms caused by indwelling catheters can be managed with propantheline bromide and opium suppositories or by oral oxybutynin. A dorsal penile nerve block performed intraoperatively with bupivacaine can help control postoperative pain.117

A caudal block is my preferred method for postoperative pain control. In most cases, the patients are comfortable for the entire day and evening of surgery, and are easily cared for at home with oral analgesia.118

Complications

Infection

Wound infection is a rare problem in hypospadias repair, especially in the prepubertal patient. As long as good viability of tissue is maintained, infection should be a minor problem. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is favored by some surgeons.119 This is probably a reasonable precaution in an extensive repair, especially in the postpubertal patient. Urinary suppression with oral antibiotics is recommended with indwelling catheters that are open to drainage in the diaper.68,120,121

Fistulas

A urethrocutaneous fistula is the most commonly reported complication of hypospadias surgery. It results from failure of healing at some point along the neourethral suture line and can range in size from pinpoint to large enough for all urine to exit at this site. Fistulas also may be associated with distal stenosis or stricture. Occasionally, small fistulas seen in the early postoperative period may close spontaneously. Operative closure should be postponed until complete tissue healing has occurred, which requires at least 6 months.122,123 A small fistula may be closed by local excision of the fistula tract followed by closure of the urethral epithelium with fine absorbable suture. Approximating several layers of well-vascularized subcutaneous tissue over this closure is important to prevent recurrence. Urinary diversion is usually not necessary in small fistula repairs. Larger fistulas may require more complicated closures, with mobilization of tissue flaps or advancement of skin flaps to ensure an adequate amount of well-vascularized tissue for a multilayered closure.122–124 Urinary diversion is often necessary with more complicated closures.

Strictures

Narrowing of the neourethra can occur anywhere along its course. However, the most common sites of stricture formation are at the meatus and at the proximal anastomosis. Most cases of meatal narrowing can be managed as an office procedure by gentle dilation in the first few postoperative weeks. Occasionally, meatotomy or meatoplasty is needed, especially when associated with a proximal fistula or neourethral diverticulum. More proximal strictures can generally be managed with dilation or an internal urethrotomy performed under vision.125 However, in recurrences or long strictures, open urethroplasty may be needed, with excision of the stricture and a primary urethral anastomosis or patch graft urethroplasty.122,123,125,126

Diverticulum

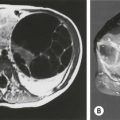

Saccular dilation of the neourethra may result from distal stenosis causing progressive dilation, contained urinary extravasation from the breakdown of the repair, or initial creation of an oversized segment of the neourethra. Classic bulging of the urethra ventrally with voiding is evident with the development of a significant diverticulum (Fig. 59-20). Urinary stasis with chronic inflammation is common. Obstruction can result from kinking of the urethra when the diverticulum distends with voiding. Repair requires excision of the redundant neourethra with primary closure to restore a uniform caliber to the urethra.127 Special attention should be paid to any narrowing of the distal neourethra as well.

Retrusive Meatus

Retraction of the meatus from its original position at the tip of the glans to a proximal glanular or subcoronal position can occur with any repair. A retrusive meatus is caused by the failure of the glansplasty closure or the breakdown of devascularized distal neourethra. Retraction is a common problem when the MAGPI procedure is used in patients whose meatus is too proximal or when too much tension is placed on the glansplasty closure.128 Correction can usually be accomplished by a repeat glansplasty, TIP, or a meatal-based flap procedure.122,128

Persistent Chordee

Residual ventral curvature after hypospadias repair can be a troublesome problem. It is usually related to inadequate release of chordee at the original procedure. Increased ventral curvature occurring as the penis grows is at least a theoretical possibility. The artificial erection has made this complication much less common. Treatment of the problem is similar to the treatment of chordee without hypospadias. Degloving of the penis and takedown of any ventral tethering tissue is accomplished by using the artificial erection technique to guide dissection. Dorsal plication, ventral excision with patching, and division of the urethra may all be necessary.123,129

Recurrent Multiple Complications

Patients with recurrent multiple complications generally have experienced multiple failed repairs that have resulted in a combination of severe complications. Extensive fibrosis of the urethra with fistulas, strictures, diverticula, and residual chordee may be present. The successful outcome of further repair depends on thorough evaluation of each complication and the use of all the techniques available to the surgeon experienced in hypospadias repair. If tissue is available, vascularized flaps or staging procedures are preferable to free grafts in a scarred phallus.130 If a free graft is necessary, it is important to obtain the most vascularized bed possible in which to place the graft. Buccal mucosa is probably the best tissue for a free graft in this type of situation.21,54,123 In patients with severe scarring and ventral skin loss, a split-thickness skin graft may be used for ventral coverage. This tissue may then be tubularized at a second stage.131

Sexual Function

Long-term results of hypospadias repair with regard to erectile function, ejaculation, and fertility are not available for the children who have undergone repairs at a younger age over the past decade. Historically, sexual difficulties after hypospadias repair have been reported. These were thought to be secondary to psychosexual factors related to surgery in childhood rather than to anatomic problems.39,41 Fertility has been assessed by semen analysis in patients after hypospadias repair.38 Higher rates of oligospermia are reported. These lower sperm counts generally occur in patients with associated anomalies such as cryptorchidism, chromosome abnormalities, varicoceles, or torsion. In a patient with an anatomically successful hypospadias repair and no associated anomalies that might affect fertility, a high potential for fertility and an adequate sexual function are expected.39,132 Only close observation of children as they enter adulthood will reveal the true incidence of sexual dysfunction and fertility problems.

Results

Complication rates in hypospadias repairs tend to be more frequent and more significant the more proximal the defect. Distal repairs with MAGPI, glans approximation procedure (GAP), TIP, and meatal-based flap have overall rates of about 1–5%.97,98,100,112,128,133–137 Fistulas are most common, with meatal stenosis being a little more likely to occur in TIP repairs.135

The proximal repairs have higher rates of fistulas, strictures, and urethral diverticuli. The formation of a diverticulum is directly related to distal narrowing. Therefore, it is important to avoid being too aggressive with the glansplasty in the proximal repairs to avoid narrowing the distal urethra. Overall, complication rates in proximal repairs are 10–50%.20,74,137–147

In postpubertal patients, the complication rates are significantly higher, which reinforces the concept of performing hypospadias repairs early in life.138

References

1. Barcat, J. Current concepts of treatment. In: Horton CE, ed. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Genital Area. Boston: Little, Brown; 1973:249–263.

2. Bellinger, MF. Embyrology of the male external genitalia. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:375–382.

3. Sommer, JJ, Stephens, FD. Dorsal urethral diverticulum of the fossa navicularis: Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. J Urol. 1980; 124:94–97.

4. Kurzrock, EA, Baskin, LS, Cunha, GR. Ontogeny of the male urethra: theory of endodermal differentiation. Differentiation. 1999; 64:115–122.

5. Rogers, DO. History of external genital surgery. In: Horton CE, ed. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Genital Area. Boston: Little, Brown; 1973:3–47.

6. Horton, CE, Devine, CJ, Baran, N. Pictorial history of hypospadias repair techniques. In: Horton CE, ed. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Genital Area. Boston: Little, Brown; 1973:237–243.

7. Bachus, LH, de Felice, CA. Hypospadias, then and now. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1960; 25:146–160.

8. Creevy, CD. The correction of hypospadias: A review. Urol Surv. 1958; 8:2–47.

9. Browne, D. An operation for hypospadias. Proc R Soc Med. 1949; 41:466–468.

10. Cuip, OS. Hypospadias with and without chordee. In: Horton CE, ed. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Genital Area. Boston: Little, Brown; 1973:315–320.

11. Byars, LT. A technique for consistently satisfactory repair of hypospadias. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1955; 100:184–190.

12. Smith, ED. Durham Smith repair of hypospadias. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:451–455.

13. Fuqua, F. Renaissance of urethroplasty: The Belt technique of hypospadias repair. J Urol. 1971; 106:782–785.

14. Coleman, JW, McGovern, JH, Marshall, VF. The bladder mucosal graft technique for hypospadias repair. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:457–462.

15. McCormack, RM. Simultaneous chordee repair and urethral reconstruction for hypospadias: Experimental and clinical studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1954; 13:257.

16. Humby, G. A one-stage operation for hypospadias. Br J Surg. 1941; 29:84–92.

17. Devine, CJ, Jr., Horton, DE. Hypospadias repair. J Urol. 1972; 85:166–172.

18. Memmelaar, J. Use of bladder mucosa in a one-stage repair of hypospadias. J Urol. 1947; 58:68–73.

19. Marshall, VF, Spellman, RM. Construction of a urethra in hypospadias using vesicle mucosal grafts. J Urol. 1955; 73:335–342.

20. Chu, LiZhong, Zheng, Yu-Hen, Sheh, Ya-Xiong, et al. One-stage urethroplasty for hypospadias using a tube constructed with bladder mucosa: A new procedure. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:463–470.

21. Duckett, JW, Coplen, D, Ewalt, D, et al. Buccal mucosal urethral replacement. J Urol. 1995; 153:1660–1663.

22. Mustardé, JC. One-stage correction of distal hypospadias and other people’s fistulae. Br J Plast Surg. 1965; 18:413–422.

23. Broadbent, TR, Woolf, RM, Tosku, E. Hypospadias: One-stage repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1961; 27:154–159.

24. Hodgson, NB. Use of vascularized flaps in hypospadias repair. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:471–481.

25. Standoli, L. One-stage repair of hypospadias: Preputial island flap technique. Ann Plast Surg. 1982; 9:81–88.

26. Duckett, JW. The island flap technique for hypospadias repair. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:513–519.

27. Sweet, RA, Schrott, HG, Kurland, R, et al. Study of the incidence of hypospadias in Rochester, Minnesota, 1940–1970, and a case control comparison of possible etiologic factors. Mayo Clin Proc. 1974; 49:52–58.

28. Duckett, JW. Hypospadias. Pediatr Rev. 1989; 11:37–42.

29. Paulozzi, LJ, Erickson, JD, Jackson, RJ. Hypospadias trends in two ultrasound surveillance systems. Pediatrics. 1997; 100:831–834.

30. Wang, MH, Baskin, LS. Endocrine disruptors, genital development, and hypospadias. J Androl. 2008; 19:499–505.

31. Kalfa, N, Philibert, P, Sultan, C. Is hypospadias a genetic, endocrine, or environmental disease, or still an unexplained malformation? Int J Androl. 2009; 32:187–197.

32. Vander Zander, LF, van Rooij, IA, Feitz, WF, et al. Aetiology of hypospadias: A systematic review of genes and environment. Human Reprod Update. 2012; 19:260–283.

33. Mau, G. Progestins during pregnancy and hypospadias. Teratology. 1981; 24:285–287.

34. Avellan, L. The incidence of hypospadias in Sweden. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975; 9:129–139.

35. Kallen, B, Mastroiacovo, P, Lancaster, PA, et al. Oral contraceptives in the etiology of isolated hypospadias. Contraception. 1991; 44:173–182.

36. Bauer, SB, Retik, AB, Colodny, AH. Genetic aspects of hypospadias. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:559–564.

37. Moriya, K, Kakizaki, H, Tanaka, H, et al. Long-term cosmetic and sexual outcome of hypospadias surgery: Norm related study in adolescence. J Urol. 2006; 176:1889–1892.

38. Moriya, K, Kakizaki, H, Tanaka, H, et al. Long-term patient reported outcome of urinary symptoms after hypospadias surgery: Norm related study in adolescents. J Urol. 2007; 178:1659–1662.

39. Rynja, SP, deJong, TP, Bosch, JL. Functional, cosmetic and psychosexual in adult men who underwent hypospadias correction in childhood. J Pediatr Urol. 2011; 7:504–515.

40. Svensson, J, Berg, R, Berg, G. Operated hypospadias: Late follow-up: Social, sexual and psychological adaptation. J Pediatr Surg. 1981; 16:134–135.

41. Berg, R, Berg, G. Penile malformation, gender identity and sexual orientation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983; 68:154–166.

42. Duckett, JW, Keating, MA. Technical challenge of the megameatus intact prepuce hypospadias variant: The pyramid procedure. J Urol. 1989; 141:1407–1409.

43. Cerasaro, TS, Brock, WA, Kaplan, GW. Upper urinary tract anomalies associated with congenital hypospadias: Is screening necessary? J Urol. 1986; 135:537–558.

44. Friedman, T, Shalom, A, Hoshen, G, et al. Detection and incidence of anomalies associated with hypospadias. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008; 23:1809–1816.

45. Khuri, FJ, Hardy, BE, Churchill, BM. Urologic anomalies associated with hypospadias. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:565–571.

46. Ritchey, ML, Benson, RC, Kramer, SA, et al. Management of müllerian duct remnants in the male patient. J Urol. 1988; 140:795–799.

47. Fallon, B, Devine, CJ, Jr., Horton, CE. Congenital anomalies associated with hypospadias. J Urol. 1976; 116:585–586.

48. Lutzker, LG, Kogan, SJ, Levitt, SB. Is routine IV urography indicated in patients with hypospadias? Pediatrics. 1977; 59:630–633.

49. Kennedy, PA. Hypospadias: A twenty-year review of 489 cases. J Urol. 1961; 85:814–817.

50. Neyman, MA, Schirmer, HKA. Urinary tract evaluation in hypospadias. J Urol. 1965; 94:439.

51. McArdle, R, Lebowitz, R. Uncomplicated hypospadias and anomalies of the upper urinary tract: Need for screening? Urology. 1975; 5:712–716.

52. Smith, DS. Hypospadias. In: Ashcraft KW, ed. Pediatric Urology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:353–395.

53. Sheldon, CA, Duckett, JW. Hypospadias. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1987; 34:1259–1272.

54. Keating, MA, Duckett, JW. Recent advances in the repair of hypospadias. Surg Ann. 1990; 22:405–425.

55. Wacksman, J. Results of early hypospadias surgery using optical magnification. J Urol. 1984; 13:516–517.

56. Belman, AB, Kass, EJ. Hypospadias repair in children less than 1 year old. J Urol. 1982; 128:1273–1274.

57. Perlmutter, AE, Morabito, R, Tarry, WF. Impact of patient age on distal hypospadias repair: A surgical perspective. Urology. 2006; 68:648–651.

58. Kelalis, PP, Bunge, R, Barkin, M, et al. The timing of elective surgery on the genitalia of male children with particular reference to undescended testes and hypospadias. Pediatrics. 1975; 56:479–483.

59. Smith, DS. Timing of surgery in hypospadias repair. Aust N Z J Surg. 1983; 53:396–397.

60. Winslow, BH, Horton, CE. Hypospadias. Semin Urol. 1987; 5:236–242.

61. Mackay, A. Hypospadias repair under the age of 1 year. Aust N Z J Surg. 1983; 53:449–452.

62. Bermudez, DM, Canning, DA, Liechty, KW. Age and proinflammatory cytokine production: Wound-healing implications for scar formation and the timing of genital surgery in boys. J Pediatric Urol. 2011; 7:324–331.

63. Schultz, JR, Klykylo, WM, Wacksman, J. Timing of elective hypospadias repair in children. Pediatrics. 1983; 71:342–351.

64. Kass, EJ, Jogan, SJ, Manley, CB, et al. Timing of elective surgery on the genitalia of male children with particular reference to the risks, benefits and psychological effects of surgery and anesthesia. Pediatrics. 1996; 97:590–594.

65. Gittes, RF, McClaughlin, AP. Injection technique to induce penile erection. Urology. 1974; 4:473–475.

66. Allen, TD, Spence, HM. The surgical treatment of coronal hypospadias and related problems. J Urol. 1968; 100:504–508.

67. Devine, CJ, Horton, CE. Chordee without hypospadias. J Urol. 1973; 110:264–271.

68. Leslie, JA, Cain, MP, Kaefer, M, et al. Corporeal grafting for severe hypospadias: A single institution experience with three techniques. J Urol. 2008; 180:1749–1752.

69. Braga, LH, Pippi Salle, JL, Dave, S, et al. Outcome analysis of severe chordee correction using tunica vaginalis as a flap in boys with proximal hypospadias. J Urol. 2007; 178:1693–1697.

70. Weiser, AC, Franco, I, Herz, DB, et al. Single layered small intestinal submucosa is the repair of severe chordee and complicated hypospadias. J Urol. 2003; 170:1593–1595.

71. Nesbit, RM. Congenital curvature of the phallus: Report of three cases with description of corrective operation. J Urol. 1965; 93:230–234.

72. Livne, PM, Gibbons, MD, Gonzales, EI. Correction of disproportion of corpora cavernosa as cause of chordee in hypospadias. Urology. 1983; 22:608–610.

73. Hollowell, JG, Keating, MA, Snyder, HM, et al. Preservation of the urethral plate in hypospadias repair: Extended applications and further experience with the onlay island flap urethroplasty. J Urol. 1990; 143:98–101.

74. Baskin, L, Duckett, JW. Dorsal tunica albuginea plication (TAP) for hypospadias curvature. J Urol. 1994; 151:1668–1671.

75. Baskins, LS, Erol, A, Li, YW. Anatomy of the neurovascular bundle: Is safe mobilization possible? J Urol. 2000; 164:977–980.

76. Decter, RM. Chordee correction by corporal rotation: The split and roll technique. J Urol. 1999; 162:1152–1155.

77. Perovic, SC, Djordjevic, ML. A new approach in hypospadias repair. World J Urol. 1998; 16:195–199.

78. Hurwitz, RS, Devine, CJ, Horton, CE, et al. Chordee without hypospadias. Dialog Pediatr Urol. 1986; 9:1–8.

79. Donnahoo, KK, Cain, MP, Pope, JC, et al. Etiology, management and surgical complications of congenital chordee without hypospadias. J Urol. 1998; 160:1120–1122.

80. Gibbons, MD, Gonzales, ET. The subcoronal meatus. J Urol. 1983; 130:739–742.

81. Gibbons, MD. Nuances of distal hypospadias. Urol Clin North Am. 1985; 12:169–174.

82. Hendren, WH. The Belt-Fuqua technique for repair of hypospadias. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:431–450.

83. Standoli, L. Vascularized urethroplasty flaps: The use of vascularized flaps of preputial and penopreputial skin for urethral reconstruction in hypospadias. Clin Plast Surg. 1980; 15:355–370.

84. Snodgrass, W, Patterson, K, Plaire, JC, et al. Histology of the urethral plate: Implications for hypospadias repair. J Urol. 2000; 164:988–990.

85. Shapiro, SR, Zaontz, MR, Scherz, HC. Hypospadias repair: Update and controversies, part 1. Dialog Pediatr Urol. 1990; 13:1–8.

86. Elder, JS, Duckett, JW, Snyder, HM. Onlay island flap in the repair of mid and distal penile hypospadias without chordee. J Urol. 1987; 138:376–379.

87. Sadove, RC, Horton, CE, McRoberts, JW. The new era of hypospadias surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1988; 15:341–354.

88. Snodgrass, W, Decter, RM, Roth, DR, et al. Management of the penile shaft skin in hypospadias repair: Alternative to Byar’s flaps. J Pediatr Surg. 1988; 23:181–182.

89. Firlit, CF. The mucosal collar in hypospadias surgery. J Urol. 1987; 137:80–82.

90. Snodgrass, WT, Koyle, MA, Baskin, LS, et al. Foreskin preservation in penile surgery. J Urol. 2006; 176:711–714.

91. Nonomura, K, Koyanagi, T, Imanaka, K, et al. One-stage total repair of severe hypospadias with scrotal transposition: Experience in 18 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1988; 23:177–180.

92. Glenn, JF, Anderson, EE. Surgical correction of incomplete penoscrotal transposition. J Urol. 1973; 110:603–605.

93. Ehrlich, RM, Scardino, PT. Simultaneous surgical correction of scrotal transposition and perineal hypospadias. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:531–537.

94. Ehrlich, RM, Scardino, PT. Surgical corrections of scrotal transposition and perineal hypospadias. J Pediatr Surg. 1982; 17:175–177.

95. Duckett, JW. MAGPI (meatoplasty and glanuloplasty). Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:513–519.

96. Mathieu, P. Traitement en un temps de l’hypospadias balanique et juxtabalanique. J Chir. 1932; 39:481.

97. Wacksman, J. Modification of the one-stage flip flap procedure to repair distal penile hypospadias. Urol Clin North Am. 1981; 8:527–530.

98. Zaontz, MR. The gap (glans approximation procedure) for glanular/coronal hypospadias. J Urol. 1989; 141:359–361.

99. Snodgrass, W. Tubularized incised plate urethroplasty for distal hypospadias. J Urol. 1994; 151:464–465.

100. Snodgrass, W, Koyle, M, Manzoni, G. Tubularized incised plate hypospadias repair: Results of a multicenter experience. J Urol. 1996; 156:839–841.

101. Snodgrass, W. Does tubularized incised plate hypospadias repair create neourethral strictures? J Urol. 1999; 162:1159–1161.

102. Cheng, EY, Vemulapalli, SN, Kropp, BP. Snodgrass hypospadias repair with vascularized dartos flap: The perfect repair for virgin cases of hypospadias? J Urol. 2002; 168:1723–1726.

103. Hendren, WH, Horton, CE, Jr. Experience with one-stage repair of hypospadias and chordee using free graft of prepuce. J Urol. 1988; 140:1250–1264.

104. Koyle, MA, Ehrlich, RM. The bladder mucosa graft for urethral reconstruction. J Urol. 1987; 138:1093–1095.

105. Dessanti, A, Iannuccelli, M, Ginesu, G, et al. Reconstruction of hypospadias and epispadias with buccal mucosa free graft as primary surgery: More than 10 years of experience. J Urol. 2003; 170:1600–1602.

106. Duckett, JW. Transverse preputial island flap technique for repair of severe hypospadias. Urol Clin North Am. 1980; 7:423.

107. Gershbaum, MD, Stock, JA, Hanna, MK. A case for 2-stage repair of perineoscrotal hypospadias with severe chordee. J Urol. 2002; 168:1727–1729.

108. Greenfield, SP, Sadler, BT, Wan, J. Two stage repair for severe hypospadias. J Urol. 1994; 152:498–501.

109. Retik, AB, Bauer, SB, Mandell, J, et al. Management of severe hypospadias with two-stage repair. J Urol. 1994; 152:749–751.

110. Shapiro, SR, Wacksman, J, Koyle, MA, et al. Hypospadias repair: Update and controversies, part 2. Dialog Pediatr Urol. 1990; 13:1–8.

111. Duckett, JW. Hypospadias. J Urol [discussion]. 1986; 136:272.

112. DiSandro, M, Palmer, JM. Stricture incidence related to suture material in hypospadias surgery. J Pediatr Surg. 1996; 31:881–884.

113. Hakim, S, Merguerian, PA, Rabonowitz, R. Outcome analysis of the modified Mathieu hypospadias repair: Comparison of stented and unstented repairs. J Urol. 1996; 156:836–838.

114. Steckler, RE, Zaontz, MR. Stent-free Thiersch-Duplay hypospadias repair with the Snodgrass modification. J Urol. 1997; 158:1178–1180.

115. McLorie, GA, Joyner, BD, Bagli, DJ, et al. A prospective randomized clinical trial to evaluate methods of postoperative care in hypospadias. Pediatrics. 1999; 104:813A.

116. VanSavage, JG, Palanca, LG, Slaughenhoupt, BL. A prospective randomized trial of dressing versus no dressing for hypospadias repair. J Urol. 2000; 164:981–983.

117. Goulding, FJ. Penile block for postoperative pain relief in penile surgery. J Urol. 1981; 126:337.

118. Thies, KC, Driessen, J, KHO, HG, et al. Longer than expected-duration of caudal analgesia with two different doses of levobupivicaine in children undergoing hypospadias repair. J Pediatr Urol. 2010; 6:585–588.

119. Duckett, JW, Kaplan, GW, Woodard, JR. Panel: Complications of hypospadias repair. Urol Clin North Am. 1980; 7:443–454.

120. Sugar, EC, Firlit, CF. Urinary prophylaxis and postoperative care of children at home with an indwelling catheter after hypospadias repair. Urology. 1988; 32:418–420.

121. Shohet, I, Alagam, M, Shafir, R, et al. Postoperative catheterization and prophylactic antimicrobials in children with hypospadias. Urology. 1983; 22:391–393.

122. Horton, CE, Jr., Horton, CE. Complications of hypospadias surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1988; 15:371–379.

123. Retik, AB, Keating, MA, Mandell, J. Complications of hypospadias surgery. Urol Clin North Am. 1988; 15:223–236.

124. Zagula, EM, Braren, V. Management of urethrocutaneous fistulas following hypospadias repair. J Urol. 1983; 130:743–745.

125. Gargolla, PC, Cai, AW, Borer, JG, et al. Management of recurrent urethral strictures after hypospadias repair: is there a role for repeat dilation or endoscopic incision? J Pediatr Urol. 2011; 7:34–38.

126. Scherz, HC, Kaplan, GW, Packer, MG, et al. Post-hypospadias repair urethral strictures: A review of 30 cases. J Urol. 1988; 140:1253–1255.

127. Zaontz, MR, Kaplan, WE, Maizels, M. Surgical correction of anterior urethral diverticula after hypospadias repair in children. Urology. 1989; 33:40–42.

128. Issa, MM, Gearhart, JP. The failed MAGPI: Management and prevention. Br J Urol. 1989; 64:169–171.

129. Vandersteen, DR, Hussman, DA. Late onset recurrent penile chordee after successful correction at hypospadias repair. J Urol. 1998; 160:1131–1133.

130. Sheldon, CA, Essig, KA. Surgical strategies in the reconstruction of the failed hypospadias: Advantages and versatility of vascular based graft/flap techniques [abstract 250]: American Urological Association Meeting. J Urol. 1990; 143:251A.

131. Ehrlich, RM, Alter, G. Split-thickness skin graft urethroplasty and tunica vaginalis flaps for failed hypospadias repairs. J Urol. 1996; 155:131–134.

132. Subanj, TB, Perovic, SV, Milcevic, RM, et al. Sexual behavior and sexual function of adults after hypospadias surgery: A comparative study. J Urol. 2004; 171:1876–1879.

133. Duckett, JW, Snyder, HM. Meatal advancement and glanuloplasty hypospadias repair after 1000 cases: Avoidance of meatal stenosis and regression. J Urol. 1992; 147:665–669.

134. Retik, AB, Mandell, J, Bauer, SB, et al. Meatal-based hypospadias repair with the use of a dorsal subcutaneous flap to prevent urethrocutaneous fistula. J Urol. 1994; 152:1229–1231.

135. Braga, LH, Lorenzo, AJ, Pippi Salle, JL. Tubularized incised plate urethroplasty for distal hypospadias: a literature review. Indian J Urol. 2008; 24:219–225.

136. Wilkinson, DJ, Farrelly, P, Kenny, SE. Outcomes in distal hypospadias: A systematic review of the Mathieu and tabularized incised pate repairs. J Pediatr Urol. 2012; 8:307–312.

137. Jayanthi, VR. The modified Snodgrass hypospadias repair: Techniques and results. Urology 2. 1983; 1:30–35.

138. Ching, CB, Wood, HM, Ross, JH, et al. The Cleveland Clinic experience with adult hypospadias patients undergoing repair: Their presentation and a new classification system. BJU Int. 2011; 107:1142–1146.

139. Hanna, MK. Single-stage hypospadias repair: Techniques and results. Urology. 1983; 21:30–35.

140. Hendren, WH, Horton, CE. Experience with one-stage repair of hypospadias and chordee using free graft of prepuce. J Urol. 1988; 140:1259–1264.

141. Robert, PE, Perlmutter, AD, Reitelman, C. Experience with 81, one-stage hypospadias/chordee repairs with free graft urethroplasties. J Urol. 1990; 144:526–529.

142. Stock, JA, Cortez, J, Scherz, HC, et al. The management of proximal hypospadias using a one-stage hypospadias repair with a preputial free graft for neourethral construction and a preputial pedicle flap for ventral skin coverage. J Urol. 1994; 152:2335–2337.

143. Fichtner, J, Fisch, M, Filipas, D, et al. Refinements in buccal mucosal graft urethroplasty for hypospadias repair. World J Urol. 1998; 16:192–194.

144. Carr, MC. Buccal mucosa grafts: Long-term follow up. Dialog Pediatr Urol. 2002; 25:5–6.

145. Hensle, TW, Kearney, MC, Bingham, JB. Buccal mucosa grafts for hypospadias surgery: Long-term results. J Urol. 2002; 168:1734–1737.

146. Braga, LH, Pippi Salle, JL, Lorenzo, AJ, et al. Comparative analysis of tubularized incised plate versus onlay island flap urethroplasty for penoscrotal hypospadias. J Urol. 2007; 178:1451–1456.

147. Snodgrass, W, Yucei, S. Tubularized incised plate for mid shaft and proximal hypospadias repair. J Urol. 2007; 177:698–702.