Hypocalcemia

Hypocalcemia is the state in which the serum ionized calcium level drops below the normal range of 1.0 to 1.3 mmol/L. This corresponds, under normal conditions, to a total serum calcium level of 2.1 to 2.5 mmol/L (8.5-10.5 mg/dL).

2. How are serum calcium and serum albumin levels related?

Approximately 50% of serum calcium is bound to albumin, other plasma proteins, and related anions, such as citrate, lactate, and sulfate. Of this, 40% is bound to protein, predominantly albumin, and 10% to 13% is attached to anions. The remaining 50% is unbound or ionized calcium. The total serum calcium level reflects both the bound and the unbound portions with a normal range of 2.1 to 2.5 mmol/L (8.5-10.5 mg/dL).

3. How is the total serum calcium corrected for a low serum albumin level?

Total serum calcium levels are corrected for hypoalbuminemia by the addition of 0.8 mg/dL to the serum calcium level for every 1.0 g/dL that the albumin level is below 4.0 g/dL. The adjusted level of total serum calcium correlates with the level of ionized calcium, which is the physiologically active form of serum calcium.

4. What is the most common cause of low total serum calcium?

Hypoalbuminemia. The ionized calcium concentration is normal. Low serum albumin is common in chronic illness and malnutrition.

5. What factors other than albumin influence the levels of serum ionized calcium?

Serum pH influences the level of ionized calcium by causing decreased binding of calcium to albumin in acidosis and increased binding in alkalosis. As an example, respiratory alkalosis, seen in hyperventilation, causes a drop in the serum ionized calcium level. A shift of 0.1 pH unit is associated with an ionized calcium change of 0.04 to 0.05 mmol/L (0.16-0.20 mg/dL). Increased levels of chelators, such as citrate, which may occur during large-volume transfusions of citrate-containing blood products, also may lower the levels of ionized calcium. Heparin may act similarly.

6. How is serum calcium regulated?

Three hormones maintain calcium homeostasis: parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D, and calcitonin. PTH acts in three ways to raise serum calcium levels: (1) stimulates osteoclastic bone resorption, (2) increases conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, increasing intestinal calcium absorption, and (3) increases renal reabsorption of calcium. Calcitonin decreases the level of serum calcium by suppressing osteoclast activity in bone. The interplay of these hormones maintains calcium levels within a narrow range in a normal individual. Calcium levels are also influenced by the presence or absence of hyperphosphatemia.

7. What steps in vitamin D metabolism may influence serum calcium levels?

Vitamin D is obtained through the diet or is formed in the skin in the presence of ultraviolet light. Vitamin D is converted to 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the liver and finally to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, the most active form of vitamin D, in the kidney. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D acts directly on intestinal cells to increase calcium absorption. Deficiency in any of these steps may cause hypocalcemia.

8. What are the major causes of hypocalcemia?

The multiple organ and hormonal regulatory systems involved in calcium homeostasis create the potential for multiple causes of hypocalcemia. The etiology of hypocalcemia must be considered in relation to the level of serum albumin, the secretion of PTH, and the presence or absence of hyperphosphatemia. Initially, hypocalcemia may be approached by a search for failure in one or more of these systems. The systems primarily involved are the parathyroid glands, bone, kidney, and liver; the following list shows the clinical entities followed by their mechanisms:

Hypoparathyroidism: decreased PTH production

Hypoparathyroidism: decreased PTH production

Hypomagnesemia: decreased PTH release, responsiveness, and action

Hypomagnesemia: decreased PTH release, responsiveness, and action

Citrate toxicity from massive blood transfusion: complexing of calcium with citrate

Citrate toxicity from massive blood transfusion: complexing of calcium with citrate

Pseudohypoparathyroidism: PTH ineffective at target organ

Pseudohypoparathyroidism: PTH ineffective at target organ

Liver disease: decreased albumin production, decreased 25-hydroxyvitamin D production, drugs that stimulate 25-hydroxyvitamin D metabolism

Liver disease: decreased albumin production, decreased 25-hydroxyvitamin D production, drugs that stimulate 25-hydroxyvitamin D metabolism

Renal disease: renal calcium leak, decreased 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production, elevated serum phosphate (Po4) from decreased Po4 clearance; drugs that increase renal clearance of calcium

Renal disease: renal calcium leak, decreased 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production, elevated serum phosphate (Po4) from decreased Po4 clearance; drugs that increase renal clearance of calcium

Bone disease: drugs suppressing bone resorption; “hungry bone syndrome”—recovery from hyperparathyroidism or hyperthyroidism

Bone disease: drugs suppressing bone resorption; “hungry bone syndrome”—recovery from hyperparathyroidism or hyperthyroidism

Phosphate load: endogenous—tumor lysis syndrome, hemolysis, and rhabdomyolysis; exogenous—phosphate-containing enemas, laxatives, and phosphorus burns

Phosphate load: endogenous—tumor lysis syndrome, hemolysis, and rhabdomyolysis; exogenous—phosphate-containing enemas, laxatives, and phosphorus burns

Pancreatitis: sequestration of calcium in the pancreas; other

Pancreatitis: sequestration of calcium in the pancreas; other

Toxic shock syndrome, other critical illness: decreased PTH production or PTH resistance

Toxic shock syndrome, other critical illness: decreased PTH production or PTH resistance

9. What physical signs suggest hypocalcemia?

The hallmark sign of acute hypocalcemia is tetany. This is characterized by neuromuscular irritability, which is usually seen when the serum ionized calcium concentration is less than 4.3 mg/dL (total serum calcium < 7-7.5 mg/dL).

Mild tetany: perioral numbness, acral paresthesias, and muscle cramps

Mild tetany: perioral numbness, acral paresthesias, and muscle cramps

Severe tetany: carpopedal spasms, laryngospasm, and focal or generalized seizures

Severe tetany: carpopedal spasms, laryngospasm, and focal or generalized seizures

Testing for Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs is useful in detecting hypocalcemia. Chvostek’s sign is an ipsilateral facial twitch elicited by percussing the facial nerve below the zygomatic arch at the angle of the jaw. Trousseau’s sign is a forearm spasm induced by inflation of an upper arm blood pressure cuff to a pressure greater than systolic blood pressure for up to 3 minutes. The spasm causes flexion of the wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints, extension of the fingers, and adduction of the thumb. It is important to note that 4% to 25% of individuals with normal calcium levels have positive responses to these tests.

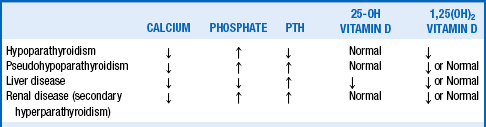

10. What laboratory tests are clinically useful in distinguishing among the causes of hypocalcemia?

Table 16-1 summarizes the laboratory findings in the conditions listed.

11. Describe the symptoms of hypocalcemia.

Early symptoms: numbness and tingling involving fingers, toes, and circumoral region

Early symptoms: numbness and tingling involving fingers, toes, and circumoral region

Neuromuscular symptoms: cramps, fasciculations, laryngospasm, and tetany

Neuromuscular symptoms: cramps, fasciculations, laryngospasm, and tetany

Cardiovascular symptoms: arrhythmias, bradycardia, and hypotension

Cardiovascular symptoms: arrhythmias, bradycardia, and hypotension

Central nervous system symptoms: irritability, paranoia, depression, psychosis, organic brain syndrome, and seizures; “cerebral tetany,” which is not a true seizure (see question 13), may also be seen in hypocalcemia; subnormal intelligence has also been reported

Central nervous system symptoms: irritability, paranoia, depression, psychosis, organic brain syndrome, and seizures; “cerebral tetany,” which is not a true seizure (see question 13), may also be seen in hypocalcemia; subnormal intelligence has also been reported

Chronic symptoms: papilledema, basal ganglia calcifications, cataracts, dry skin, coarse hair, and brittle nails

Chronic symptoms: papilledema, basal ganglia calcifications, cataracts, dry skin, coarse hair, and brittle nails

Symptoms reflect the absolute calcium concentration and the rate of fall in calcium concentration. Individuals may be unaware of symptoms because of gradual onset and may realize they have experienced an abnormality only when their sense of well-being improves with treatment.

12. What radiographic findings may be present with hypocalcemia?

Calcifications of basal ganglia may occur in the small blood vessels of that region. These occasionally may cause extrapyramidal signs but usually are asymptomatic. Of note, 0.7% of routine computed tomography (CT) scans of the brain show calcification of the basal ganglia.

13. What is cerebral tetany, and how does it differ from a true seizure?

Cerebral tetany manifests as generalized tetany without loss of consciousness, tongue biting, incontinence, or postictal confusion. Anticonvulsants may relieve the symptoms, but because they enhance 25-hydroxyvitamin D catabolism, they also may worsen the hypocalcemia.

14. How does hypocalcemia affect cardiac function?

Calcium is involved in cardiac automaticity and is required for muscle contraction. Hypocalcemia can therefore result in arrhythmias and reduced myocardial contractility. This decrease in the force of contraction may be refractory to pressor agents, especially those that involve calcium in their mechanism of action. Through this process, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers can exacerbate cardiac failure. With low serum calcium, the QT interval is prolonged, and ST changes may mimic those seen in ischemia. Although the relationship is variable, the calcium level inversely correlates moderately well with the interval from the Q-wave onset to the peak of the T wave.

15. What are the potential ophthalmologic findings in hypocalcemia?

Papilledema may occur with subacute and chronic hypocalcemia. Patients are most often asymptomatic, and the papilledema usually resolves with normalization of the serum calcium level. If symptoms develop or if papilledema does not resolve when the patient is normocalcemic, a cerebral tumor and benign intracranial hypertension must be excluded. Optic neuritis with unilateral loss of vision occasionally develops in hypocalcemic patients. Lenticular cataracts also may occur with long-standing hypocalcemia but usually do not change in size after hypocalcemia is corrected.

16. With which autoimmune disorders is hypocalcemia sometimes associated?

Hypoparathyroidism may result from autoimmune destruction of the parathyroid glands. This disorder has been associated with adrenal, gonadal, and thyroid failure as well as with alopecia areata, vitiligo, and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. This combination of conditions, each associated with organ-specific autoantibodies, has been termed the autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome, type 1 (see Chapter 52).

17. Hypocalcemia is frequently encountered in intensive care settings. What are the potential causes?

Low total serum calcium levels, which are found in 70% to 90% of patients receiving intensive care, result from multiple causes, including:

Administration of anionic loads causing chelation (i.e., citrate, lactate, oxalate, bicarbonate, phosphate, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and radiographic contrast media)

Administration of anionic loads causing chelation (i.e., citrate, lactate, oxalate, bicarbonate, phosphate, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and radiographic contrast media)

Rapid blood transfusion with citrate ion as a preservative and anticoagulant therapy

Rapid blood transfusion with citrate ion as a preservative and anticoagulant therapy

Parathyroid failure and decreased vitamin D synthesis in severe illness

Parathyroid failure and decreased vitamin D synthesis in severe illness

Sepsis inducing some degree of resistance to the biologic effects of PTH

Sepsis inducing some degree of resistance to the biologic effects of PTH

Because of all the preceding factors, it is recommended that ionized serum calcium rather than total serum calcium be measured in patients with severe illness.

18. Hypercalcemia is not unusual in patients with cancer. What conditions may lead to hypocalcemia in this patient group?

Tumor lysis syndrome, which causes hyperphosphatemia and associated formation of intravascular and tissue calcium-phosphate complexes.

Tumor lysis syndrome, which causes hyperphosphatemia and associated formation of intravascular and tissue calcium-phosphate complexes.

Multiple chemotherapeutic agents and antibiotics (amphotericin B and aminoglycosides) induce hypomagnesemia, which in turn impairs secretion of PTH and causes resistance to PTH in skeletal tissue.

Multiple chemotherapeutic agents and antibiotics (amphotericin B and aminoglycosides) induce hypomagnesemia, which in turn impairs secretion of PTH and causes resistance to PTH in skeletal tissue.

Thyroid surgery and neck irradiation with transient or permanent hypoparathyroidism.

Thyroid surgery and neck irradiation with transient or permanent hypoparathyroidism.

Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid and pheochromocytoma may secrete calcitonin and on rare occasions cause hypocalcemia.

Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid and pheochromocytoma may secrete calcitonin and on rare occasions cause hypocalcemia.

19. What drugs may cause hypocalcemia?

Phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone, rifampin, and glutethimide increase hepatic metabolism of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and may thereby cause hypocalcemia. Aminoglycosides, diuretics (furosemide), and chemotherapeutic agents that induce renal magnesium wasting, and laxatives or enemas that create a large phosphate load, also may be associated with hypocalcemia. Bisphosphonates, heparin, ketoconazole, isoniazid, fluoride, foscarnet, and glucagon may also induce hypocalcemia by a variety of mechanisms.

20. Which vitamin D metabolite is best for assessing total body vitamin D stores, 25-hydroxyvitamin D or 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D?

The serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level best reflects total body vitamin D stores. The conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D is tightly controlled, and the level of serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D is usually maintained despite significant vitamin D depletion. Increases in PTH (secondary hyperparathyroidism) stimulate increased conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in this situation.

21. How is hypocalcemia treated?

Asymptomatic hypocalcemia requires supplementation with oral calcium and vitamin D derivatives to maintain the serum calcium level at least in the 7.5 to 8.5 mg/dL range. When the serum calcium falls acutely to a level at which the patient is symptomatic, intravenous administration is recommended. The dosage of calcium depends on the amount of elemental calcium present in a given preparation (Table 16-2). For a hypocalcemic emergency, 90 mg of elemental calcium may be given as an intravenous bolus, or alternatively 100 to 300 mg of elemental calcium may be given intravenously over 10 minutes, followed by an infusion of 0.5 to 2.0 mg/kg/h.

TABLE 16-2.

ELEMENTAL CALCIUM CONTENT OF COMMONLY USED PREPARATIONS

| Preparation | Oral Dose | Elemental Calcium (mg) |

| Calcium citrate: | ||

| Citracal | 950 mg | 200 |

| Calcium acetate: | ||

| PhosLo | 667 mg | 169 |

| Calcium carbonate: | ||

| Tums | 500 mg | 200 |

| Tums Ex | 750 mg | 300 |

| Oscal | 625 mg | 250 |

| Oscal 500 | 1250 mg | 500 |

| Calcium 600 | 1500 mg | 600 |

| Titralac (suspension) | 1000 mg/5 mL | 400 |

| Intravenous Agent | Volume | Elemental Calcium (mg) |

| Calcium chloride | 2.5 mL of 10% solution | 90 |

| Calcium gluconate | 10 mL of 10% solution | 90 |

| Calcium gluceptate | 5 mL of 22% solution | 90 |

22. When is treatment with 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol) indicated?

Under normal conditions, 25-hydroxyvitamin D is converted to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol) in the kidney through the stimulatory influence of PTH. Two conditions can therefore make the body unable to produce adequate amounts of calcitriol: hypoparathyroidism and renal failure. Because calcitriol is essential for normal intestinal calcium absorption, oral calcitriol (Rocaltrol) supplementation is indicated in patients who have either hypoparathyroidism or chronic renal failure. Of note, because vitamin D has weak biologic activity, these patients may be given large dosages of vitamin D (50,000-100,000 U/day) if calcitriol is unavailable.

23. Can recombinant human PTH (rhPTH) be used in the treatment of hypocalcemia?

Ariyan, CE, Sosa, JA. Assessment and management of patients with abnormal calcium. Crit Care Medicine. 2004;32:S146–S154.

Dickerson, RN. Treatment of hypocalcemia in critical illness. Nutrition. 2007;23:358–361.

Kastrup EK, ed. Drug Facts and Comparisons. St. Louis: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2003.

Kronenberg, HM, Melmed, S, Polonsky, KS, et al, Hypocalcemic disorders. In William Textbook of Endocrinology, ed 11Philadelphia: Saunders;2008;1241–1249.

Lind, L. Hypocalcemia and parathyroid hormone secretion in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:93–98.

McEvoy, GK, Calcium salts. In AHFS Drug Information. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists: 2007;2655–2661.

Moe, SM. Disorders involving calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium. Primary Care. 2008;35(2):215–237.

Potts, JT, Hypocalcemia. Kasper DL, ed. Principles of Internal Medicine, ed 16 New York: McGraw-Hill;2005;2263–2268.

Sarko, J. Bone and mineral metabolism. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:703–721.

Shane, E, Hypocalcemia. pathogenesis, differential diagnosis and management. Favus MJ, ed. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism, ed 4 Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;1999;223–226.

Winer, KK, Ko, CW, Reynolds, JC, et al, Long-term treatment of hypoparathyroidism. a randomized controlled study comparing parathyroid hormone-(1–34) versus calcitriol and calcium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:4214–4220.