Chapter 52

Hypertensive Crisis

Anish K. Agarwal, MD, MPH, Christopher J. Rees, MD and Charles V. Pollack, MA, MD, FACEP, FAAEM, FAHA

1. What is a hypertensive crisis?

2. How commonly do these situations occur?

3. What are the causes of hypertensive crisis?

4. What are the common clinical presentations of hypertensive crisis?

5. What historical information should be obtained?

A thorough medication history is also essential. The patient’s current medications need to be reviewed and updated to include timing, dosages, recent changes in therapy, last doses taken, and compliance. Patients should also be questioned about over-the-counter medication usage and recreational drug use because these agents may also affect blood pressure.

6. How should the physical examination be focused?

7. What laboratory and ancillary data should be obtained?

8. What are the cardiac manifestations of hypertensive emergencies?

9. What are the central nervous system manifestations of hypertensive emergency?

10. What are the renal manifestations of hypertensive emergencies?

11. What are the pregnancy-related issues with hypertensive emergency?

Preeclampsia is a syndrome that includes hypertension, peripheral edema, and proteinuria in women after the twentieth week of gestation. Eclampsia is the more severe form of the syndrome, with severe hypertension, edema, proteinuria, and seizures.

12. What are general issues in the treatment of hypertensive urgency?

13. What are general issues in treating hypertensive emergencies?

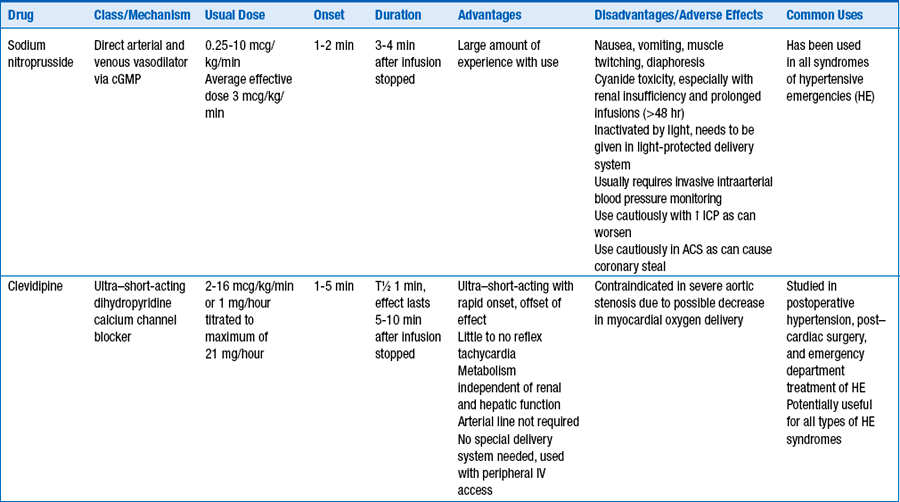

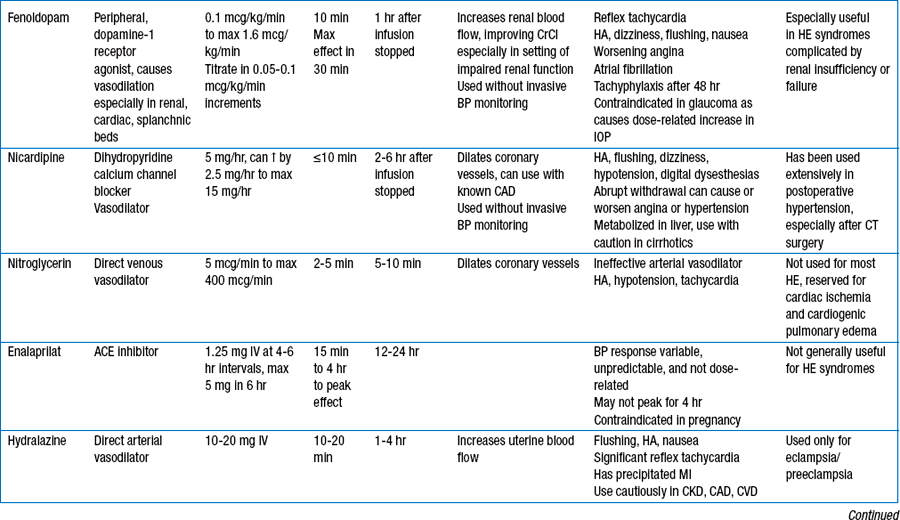

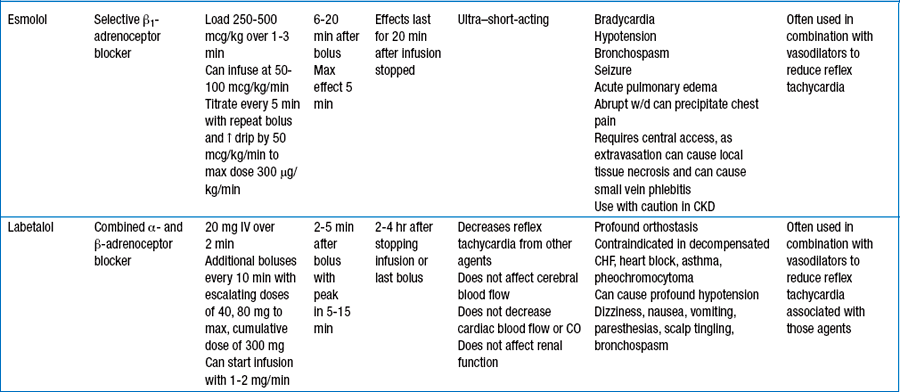

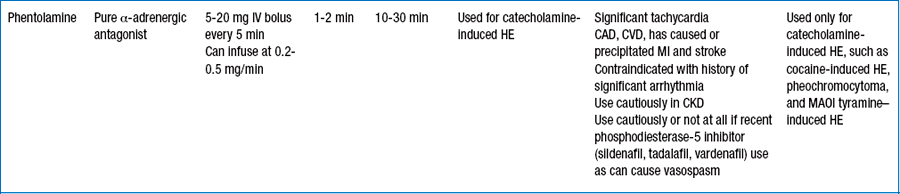

14. What specific agents are used for treating patients with hypertensive emergencies?

Table 52-1 reviews specific agents available for use.

15. Are different agents more helpful for different clinical situations?

Table 52-2 reviews specific agents recommended for specific situations.

TABLE 52-2

SPECIFIC ANTIHYPERTENSIVE AGENTS SUGGESTED FOR SPECIFIC HYPERTENSIVE EMERGENCY SYNDROMES

| Syndrome | Suggested Anti hypertensive Agents |

| Aortic dissection | Nitroprusside, often in combination with esmolol, labetalol Nicardipine with β-blocker β-Blocker alone |

| Acute pulmonary edema | Nitroglycerin preferred Fenoldopam Nicardipine Clevidipine |

| Acute coronary syndrome | β-Blocker Nitroglycerin Clevidipine |

| HE with acute or chronic renal failure | Labetalol Nicardipine Fenoldopam Clevidipine |

| Eclampsia | Labetalol Nicardipine Hydralazine (all in conjunction with magnesium sulfate) |

| Acute ischemic stroke or ICH (If expert guidance deems BP control necessary) |

Nicardipine Labetalol Clevidipine |

| Hypertensive encephalopathy | Clevidipine Labetalol Esmolol Nicardipine Fenoldopam Nitroprusside |

| Adrenergic crisis with HE | Phentolamine Nitroprusside β-Blocker |

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Website

1. Adams, H.P., Jr., DelZoppo, G., Alberts, M.J., et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cerebrovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups. Stroke. 2007;38:1655–1711.

2. Amin, A. Parenteral medication for hypertension with symptoms. Ann Em Med. 2008;51:S1–S15.

3. Elliott, W.J. Clinical features in the management of selected hypertensive emergencies. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;48:316–325.

4. Flanigan, J.S., Vitberg, D. Hypertensive emergencies and severe hypertension: what to treat, who to treat, and how to treat. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90:439–451.

5. Gray, R.O. Hypertension. In Marx J.A., Hockberger R.S., Walls R.M., eds.: Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice, ed 6, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2006.

6. Haas, A.R., Marik, P.E. Current diagnosis and management of hypertensive emergency. Semin Dial. 2006;19:502–512.

7. Hebert, C.J., Vitdt, D.G. Hypertensive crises. Prim Care. 2008;35:475–487.

8. Marik, P.E., Varon, J. Hypertensive crisis: challenges and management. Chest. 2007;131:1949–1962.

9. National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC-7). Publication no. NIH 03-5233. Bethesda, Md: NHLBI; 2003. pp. 54–55

10. Qureshi, A.I., Bliwise, D.L., Bliwise, N.G., et al. Rate of 24-hour blood pressure decline and mortality after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a retrospective analysis with a random effects regression model. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:480–485.

11. Stewart, D.L., Feinstein, S.E., Colgan, R. Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies. Prim Care. 2006;33:613–623.

12. Strandgaard, S., Olesen, J., Skinhoj, E., et al. Autoregulation of brain circulation in severe arterial hypertension. Br Med J. 1973;1:507–510.

13. Zampaglione, B., Pascale, C., Marchisio, M., et al. Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies: prevalence and clinical presentation. Hypertension. 1996;27:144–147.