16.3 Hypertension

Introduction

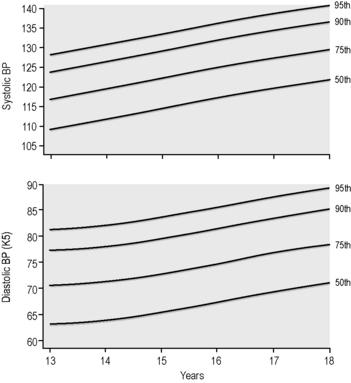

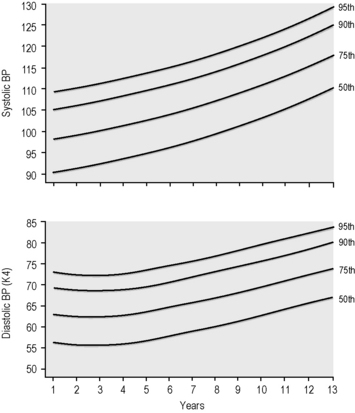

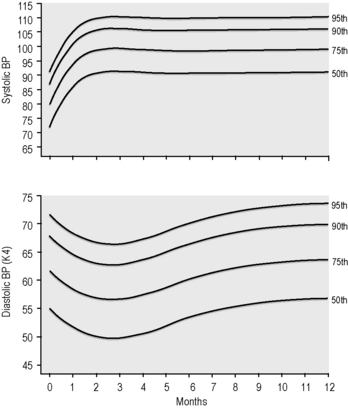

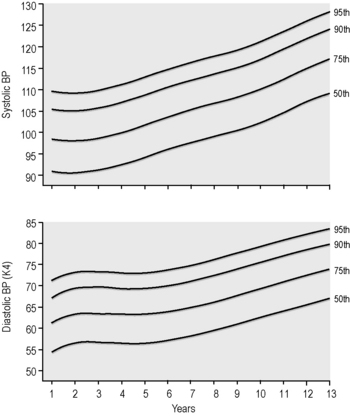

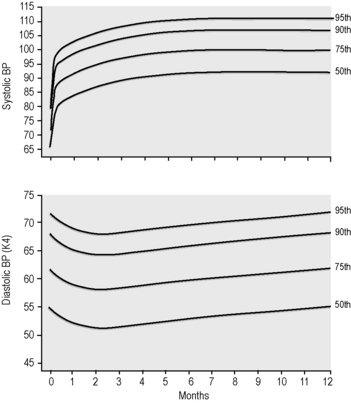

Hypertension is defined as BP that is consistently above the 95th percentile for age, gender and height (nomograms are available with these data and should be present in both the emergency department (ED) and paediatric wards) (Table 16.3.1).

Data obtained with permission from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the United States National Institutes of Health.

Ideally, all children presenting to ED should have a BP measurement.

Investigations

Investigations to be considered in ED include:

Treatment

Hypertensive encephalopathy

Aim initially for 25% reduction towards target BP (upper limit of normal systolic – see Table 16.3.1) in the first 12–24 hours, then the reduction should be slow, over 24–48 hours. Neglecting to lower the blood pressure can lead to permanent disability or death. Acutely lowering the blood pressure to normal is also contraindicated, because a rapid drop in blood pressure to normal can produce tissue ischaemia. This may manifest as shock (despite normal to slightly elevated blood pressure values), encephalopathy leading to cerebral injury, retinopathy or optic nerve infarction leading to blindness, hypoventilation and apnoea.

Peripheral vasodilators

Avoid diazoxide because it has a too-rapid, large and sustained effect.

Beta-blockers

Less severe hypertension and oral management after control of malignant hypertension

Vasodilators

Flynn J.T. What’s new in pediatric hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2001;3:503-510.

Julius S. Clinical and physiological significance of borderline hypertension in youth. Paediatr Clin N Am. 1978;25:35-45.

Mouin G.S., Arant B.S. Hypertension. In: Barakat A.Y., editor. Renal disease in children – clinical evaluation and diagnosis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1990:307-328.

Report of the second task force on blood pressure control in children. Paediatrics. 1987;79:1-25.

Report of the task force on blood pressure control in children. Paediatrics. 1977;59:797-820.

Rocchini A.P. Pediatric hypertension 2001. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2002;17:385-389. [review]

Sorof J.M., Portman R.J. White coat hypertension in children with elevated casual blood pressure. J Paediatr. 2000;137:493-497.

Vogt B.A. Hypertension in children and adolescents. Curr Thera Res Clin Exp. 2001;62:283-297.

Wells T.G. Trials of antihypertensive therapies in children. Blood Pressure Monitor. 1999;4:189-192.