47 Hypertension

Etiology And Pathogenesis

Definitions

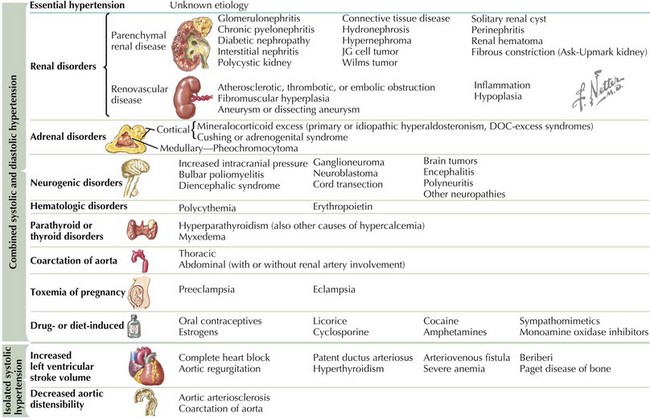

There are many causes of hypertension (Figure 47-1). Whereas BP for which a clear cause can be determined is described as secondary hypertension, hypertension without a clear correctable cause is referred to as primary or essential hypertension. This is necessarily a diagnosis of exclusion.

Clinical Presentation

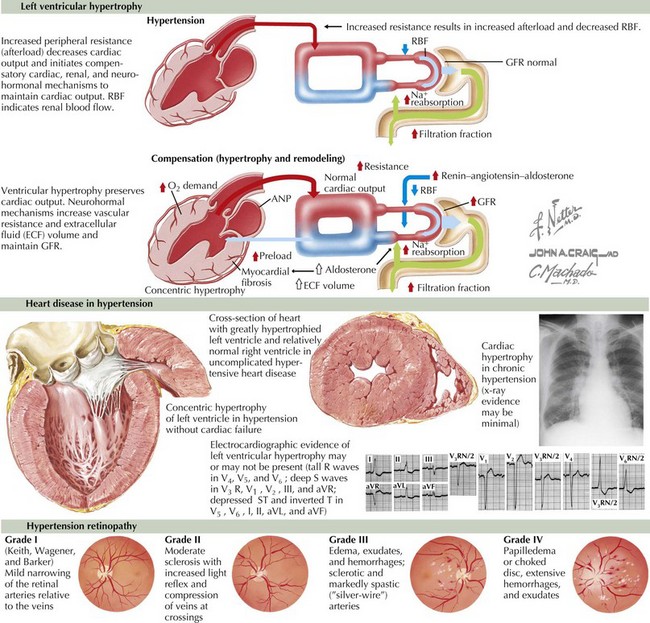

Most children with hypertension have not had years of exposure to elevated BPs. Therefore, unlike their adult counterparts, the clinical signs and symptoms in children and adolescents are generally more indicative of the cause of their disease rather than stigmata of end-organ damage from chronic hypertension. Although hypertensive nephropathy, left ventricular hypertrophy, congestive heart failure, hypertensive retinopathy, and stroke can be seen in children with long-standing, severe hypertension, they are much less common than in adults with chronic hypertension (Figure 47-2).

Evaluation

Diagnostic Approach

Before making a diagnosis of hypertension, it is important to rule out immediate causes of transient BP elevations such as acute pain, anxiety, or medication exposure. After such causes have been ruled out, the diagnostic approach in a patient with hypertension can be organized as follows: (1) define the degree of hypertension, (2) investigate end-organ damage, and (3) evaluate for possible causes of secondary hypertension (see Figure 47-1).

Secondary, as opposed to primary, hypertension is more common in children than adults, in whom primary or essential hypertension is overwhelmingly the most common cause. Generally, secondary hypertension is more likely in patients who (1) have stage 2 hypertension, (2) are young (i.e., not adolescents), and (3) have signs or symptoms of systemic disease or have a personal or family medical history of those conditions. As summarized in Figure 47-1, there are numerous causes of secondary hypertension. The history and physical examination should screen for signs and symptoms of causes of secondary hypertension. The physical should include a measurement of height and weight to calculate body mass index. Upper and lower extremity BPs must always be measured. Additional studies should be tailored to the individual patient based on their presentation. Studies should be divided between those seeking the cause of secondary hypertension and those that identify the stigmata of hypertensive end-organ damage.

Management

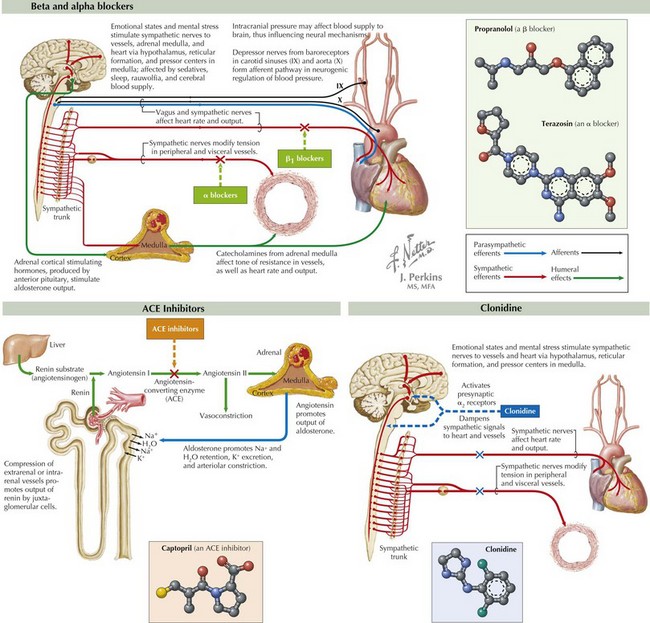

Indications for pharmacologic intervention include insufficient response to therapeutic lifestyle modifications and identification of secondary hypertension, which cannot be corrected otherwise. There is no consensus regarding the choice of antihypertensive medications, although dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers such as amlodipine are frequently first-line medications in many groups. Treatment choice is empiric and generally guided by the cause of the hypertension, especially in secondary hypertension. Medication classes include calcium channel blockers, β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and diuretics (Figure 47-3). Other agents such as clonidine, prazosin, and minoxidil are primarily used by subspecialists (see Figure 47-3). Data regarding pediatric dosing of most antihypertensive medications are expanding.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC7 Report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560-2572.

National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555-576.

Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999-2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1728-1732.

Sorof J, Daniels S. Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions. Hypertension. 2002;40:441-447.