124 Hyperpigmented Skin Disorders

Etiology And Pathogenesis

Hyperpigmented skin lesions can be described as being either circumscribed or diffuse in nature. Focal areas of hyperpigmentation reflect local influences ranging from the degree of ultraviolet radiation to biochemical signaling from neighboring keratinocytes to inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Disorders with diffuse hyperpigmentation may in part be caused by increased production of melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) as exemplified in conditions such as Addison’s disease. MSH is a byproduct of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), secretion from the pituitary and stimulates the melanocytes’ melanin production. Disruption of the production, maturation, or transportation of melanosomes results in many of the conditions discussed within this chapter. A discussion of nevi and disorders of melanocyte overgrowth is provided in Chapter 126.

Circumscribed Hyperpigmented Skin Lesions

Lentigines

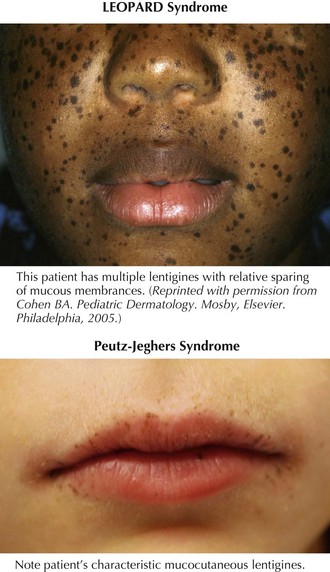

Lentigines are round, brown to black macules, 4 to 10 mm in diameter that increase in number during adolescence and, at times, can be almost indistinguishable from ephelides. Clinically, lentigines occur anywhere on the body, not just in sun-exposed areas, and do not fade in the winter. Lentigines are quite common and benign when few in number. However, when multiple, lentigines constitute the primary clinical feature of a number of syndromes. The most important syndromes with lentigines as a defining feature are LEOPARD (lentigines, electrocardiogram abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormal genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness) syndrome, also known as multiple lentiginous syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and Carney’s complex (Figure 124-1 and Table 124-1). The clinician evaluating a patient with innumerable lentigines on examination should keep the above diagnoses in mind, especially if lentigines are noted on mucosal surfaces or cross the vermillion border because these are not features of benign lentiginosis.

| Lentigines Distribution | Defining Features | |

|---|---|---|

| LEOPARD syndrome | Neck and upper trunk (less often face, arms, palms, soles, and genitalia) |

CALS, café-au-lait spots; GI, gastrointestinal.

Café-au-Lait Spots

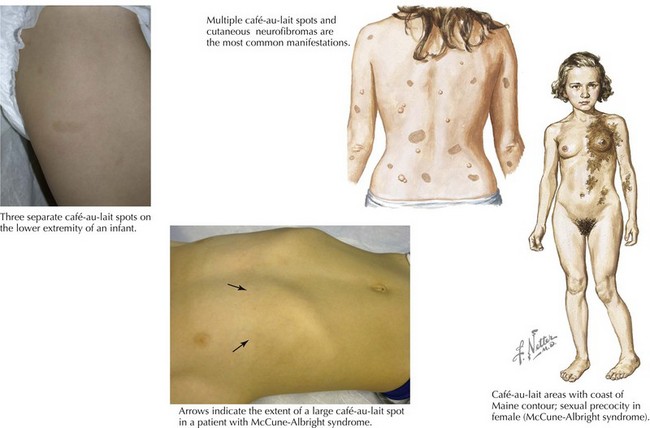

The two most common disorders in which CALS are the principal cutaneous feature and may be the primary clinical finding at the time of diagnosis are neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) and McCune-Albright syndrome. The CALS seen in NF1 are multiple and have a smooth circumference often compared to the “coast of California” (Figure 124-2). The number or distribution of CALS is not associated with the severity of disease in NF1. Other principal cutaneous findings in NF1 are described in Table 124-2. Although one or two CALS are quite common, fewer than 1% of children younger than 5 years of age have more than five CALS without having NF1 or the newly described Legius’ syndrome. Recent literature suggests that many patients previously labeled as having mild NF-1 in fact have an “NF-like syndrome” termed Legius’ syndrome, resulting from the autosomal dominant inheritance of a mutation in the SPRED-1 gene. Legius’ syndrome is characterized by multiple CALS, skin fold freckling, and an increased risk of macrocephaly and learning disabilities but without the other distinguishing features of NF-1 (see Chapter 76 for diagnostic criteria for NF-1). The CAL of McCune-Albright syndrome tends to be unilateral and large, stops abruptly at the midline, creating a segmental appearance, and has a jagged border likened to the “coast of Maine” (see Figure 124-2). Other associated features of McCune-Albright syndrome include precocious puberty and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, although many children with large segmental café-au-lait macules have no associated syndrome. The clinician should consider the number and size of CALS along with other salient features by examination and history to guide their workup.

| Age of Onset | Clinical Findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Freckling | 3-5 years old | Located in the skin folds of the axilla and inguinal area |

| Neurofibromas | Develop after puberty | Fleshy subcutaneous nodules with a violaceous hue occurring anywhere on the body |

| Plexiform neurofibromas | Present at birth or shortly thereafter | Soft tissue swelling often underlying a large, irregular CALS with overlying hypertrichosis; can grow rapidly, resembling a “bag of worms” |

CALS, café-au-lait spots.

Mastocytosis

The term mastocytoma is used if only a few isolated lesions are present, but urticaria pigmentosa is defined by the presence of multiple smaller lesions. Mastocytomas typically develop in infancy manifesting as isolated flesh-colored to yellow-orange papules or plaques with a classic “peau d’orange” (orange peel) surface (Figure 124-3). Urticaria pigmentosa presents as multiple, tens to hundreds, of papules and plaques found throughout the skin, typically sparing the palms and soles. Urticaria pigmentosa is the most common form of mastocytosis and clinically can be mistaken for other hyperpigmented lesions ranging from CALS to purpura. Last, diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis is not as common as the two previous forms and reflects diffuse infiltration of the skin with mast cells, giving the skin a thickened and doughy texture with a yellow discoloration.

Symptoms from cutaneous mastocytosis result from mast cell release of proinflammatory mediators such as histamine and prostaglandins. Local release produces edema, surrounding erythema, and even the formation of vesicles or bullae that may mimic cutaneous herpes or a bullous disorder of childhood. Systemic release can manifest as a range of symptoms, including flushing, colicky abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, hypotension, and rarely wheezing and respiratory distress. Beyond recognizing its typical appearance, the diagnosis of mastocytosis can be made by eliciting a positive Darier’s sign. The Darier’s sign involves stroking a solitary lesion to trigger mast cell degranulation, leading to the appearance of edema, erythema, and occasionally vesiculation at the site (see Figure 124-3). The mainstay of management of children with mastocytosis involves avoidance of the triggers of mast cell degranulation, including physical triggers (friction, pressure, or extremes in temperature), certain medications (aspirin, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAID], opiates, amphotericin, topical polymyxin B), systemic anesthetics (pancuronium, decamethonium), alcohol, and iodine contrast media. Symptoms can be controlled with nonsedating histamine type 1 antagonists such as loratadine or cetirizine, and only rarely is an epinephrine pen needed for a history of severe reactions.

Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation

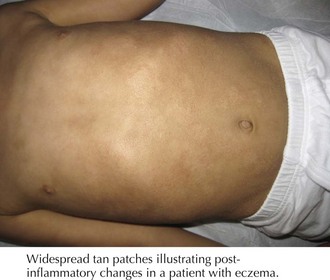

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is commonly seen throughout childhood. Local inflammatory mediators stimulate melanin production by melanocytes, leaving areas of hyperpigmentation in a distribution pattern consistent with the prior inflammatory insult (Figure 124-4). Common causes in childhood include eczematous eruptions, acne, mechanical trauma, and skin infections. Individuals with darker complexions are most often affected. Management involves treating any ongoing inflammation, particularly important in cases of atopic dermatitis and acne vulgaris, and appropriate sunscreen to avoid further hyperpigmentation, and the pigmentation will fade over months to years.

Linear Circumscribed Hyperpigmented Lesions

Incontinentia Pigmenti

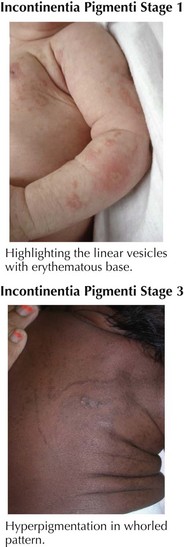

The most important diagnosis to consider in cases of hyperpigmentation following the lines of Blaschko is incontinentia pigmenti (IP; Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome). IP is an X-linked dominant disorder affecting largely girls because boys typically die in utero, and has been attributed to a mutation in nuclear factor-κB essential modulator (NEMO). The cutaneous component of the syndrome has four distinct phases: vesicular, verrucous, hyperpigmented, and hypopigmented. The vesicular phase is noted in the first 2 weeks of life with vesicles on an inflammatory base following a linear pattern on the trunk and extremities (Figure 124-5). With any blistering in the neonatal period, herpetic or bacterial infections should always be considered. In the vesicular stage, leukocytosis and peripheral eosinophilia are typically present. The vesicular phase typically fades by 4 months and is followed by the eruption of verrucous papules and plaques in a linear distribution on the extremities that fade by 6 months of age. The third stage, noted between 12 and 26 weeks and lasting up until young adulthood, is characterized by whorls of hyperpigmentation on the torso and extremities following the lines of Blaschko, which do not occur in the same areas affected in stages 1 and 2 (see Figure 124-5). Stage IV develops in adulthood and involves streaks of hypopigmentation and alopecia most commonly affecting the extremities. The importance of making of a diagnosis of IP is that this syndrome is associated with multiple noncutaneous findings involving the following: teeth (absence of teeth, conical or peg-shaped teeth), nails (nail dystrophy, subungual tumors), hair (alopecia), eyes (strabismus, optic atrophy, retinal neovascularization, placing infants at risk for retinal detachment), and the central nervous system (infantile spasms and seizures, spastic paralysis, and mental retardation). Children with IP should be followed by a pediatric ophthalmologist or retinal specialist, especially during the first year of life, and be monitored for seizures.

Bauer AJ, Statakis CA. The lentiginoses: cutaneous markers of systemic disease and a window to new aspects of tumourigenesis. J Med Genet. 2005;42:801-810.

Berlin AL, Paller AS, Chan LS. Incontinentia pigmenti: a review and update on the molecular basis of pathophysiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:169-187.

Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

Briley LD, Phillips CM. Cutaneous mastocytosis: a review focusing on the pediatric population. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:757-761.

Lacz NL, Vafaie J, Kihiczak NI, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a common but troubling condition. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:362-365.

Sinha S, Shwartz RA. Juvenile acanthosis nigricans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:502-508.

Spurlock G, Bennett E, Chuzhanova N, et al. SPRED1 mutations (Legius syndrome): another clinically useful genotype for dissecting the neurofibromatosis type 1 phenotype. J Med Genet. 2009;46:431-437.