100 Hyperbilirubinemia

Etiology and Pathogenesis

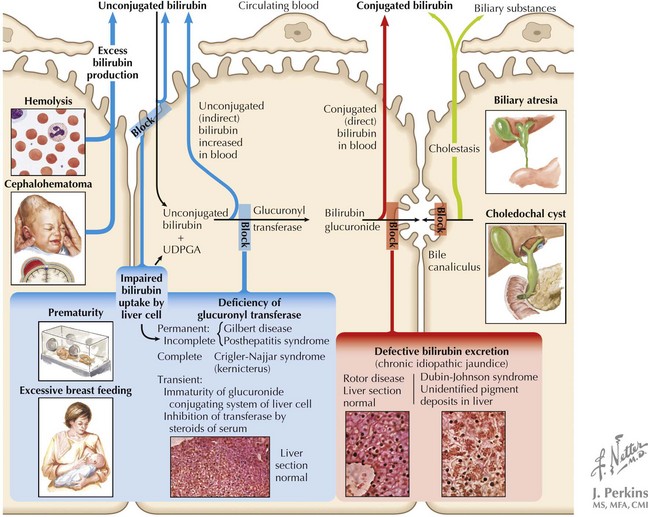

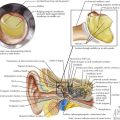

Because of multiple different etiologies, some infants develop more severe hyperbilirubinemia. Increased bilirubin production can occur in infants with increased RBC breakdown (G6PD [glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase] deficiency, ABO incompatibility, cephalohematoma) or elevated total body RBC stores (polycythemia, infants of diabetic mothers). Decreased bilirubin conjugation also contributes to hyperbilirubinemia in some infants because of decreased activity of UDPGT in Crigler-Najjar and Gilbert’s syndromes. Additionally, breastfeeding jaundice can occur early in the neonatal period in the setting of poor breast milk supply and associated dehydration and decreased stool output in an exclusively breastfed infant. In contrast, breast milk jaundice usually peaks during the second week of life and may take several more weeks to resolve completely. The mechanism of this process is not entirely understood but may involve components of breast milk inhibiting hepatic conjugating enzymes or increasing enterohepatic circulation. All of the aforementioned processes, because of their position in the bilirubin pathway, cause unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia (Box 100-1 and Figure 100-1).

Box 100-1 Selected Differential Diagnosis of Unconjugated and Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

| Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia | Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia |

|---|---|

G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; IDM, infant of a diabetic mother; TORCH, toxoplasmosis or Toxoplasma gondii, other infections, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus; UTI, urinary tract infection.

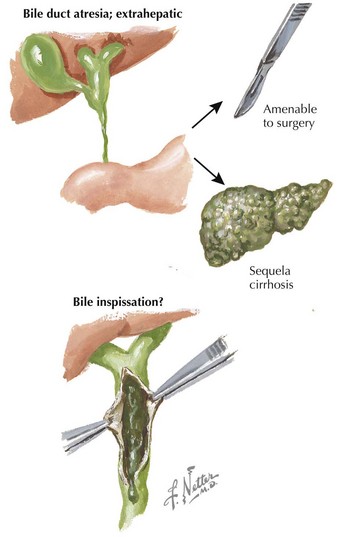

Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia occurs when the defective step exists after the conjugation of bilirubin, specifically involving defects in bile flow resulting in neonatal cholestasis (see Figure 100-1). The differential diagnosis of neonatal cholestasis is vast, including structural anomalies such as biliary atresia, choledochal cysts, and Alagille syndrome, metabolic disorders, including α-1 antitrypsin deficiency, galactosemia, and tyrosinemia, and endocrinopathies such as hypothyroidism (Figure 100-2). Additionally, infectious causes include viral (cytomegalovirus, HIV, herpes simplex virus), and bacterial (sepsis, urinary tract infections), and parasitic infections have been associated with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Other causes of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia include inherited deficiencies in excretion (Dubin-Johnson and Rotor’s syndromes), chromosomal disorders, parenteral nutrition, vascular and neoplastic processes, and idiopathic neonatal hepatitis (see Box 100-1).

Clinical Presentation

Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

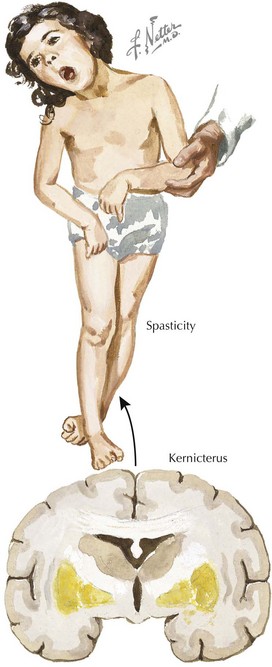

At severe levels of hyperbilirubinemia, infants may have signs of acute bilirubin encephalopathy, with early signs that include lethargy, hypotonia, decreased activity, and poor suck. Untreated, this can progress over the course of days as infants become irritable, stuporous, and eventually comatose, with decreased or no feeding, hypertonia, retrocollis, opisthotonus, fever, apnea, and a shrill cry. Prolonged severe hyperbilirubinemia results in kernicterus, which is permanent neurologic damage caused by unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, most notably in the basal ganglia and cranial nerve nuclei. Kernicterus is characterized by athetoid cerebral palsy, auditory disturbances, impaired upward gaze, and dysplasia of the primary teeth (Figure 100-3). Cognitive damage may also occur. Although the risk of kernicterus increases with increased levels of bilirubin, other clinical features appear to modify the risk, including prematurity, albumin binding capacity, duration of hyperbilirubinemia, and the presence of comorbid conditions. Although kernicterus decreased in frequency over the course of the 20th century, new cases continue to be reported, with shortened hospital stays and a resurgence of breastfeeding now requiring a high level of vigilance and the implementation of universal systematic monitoring protocols to avoid further cases of this devastating but preventable disease.

Evaluation and Management

Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

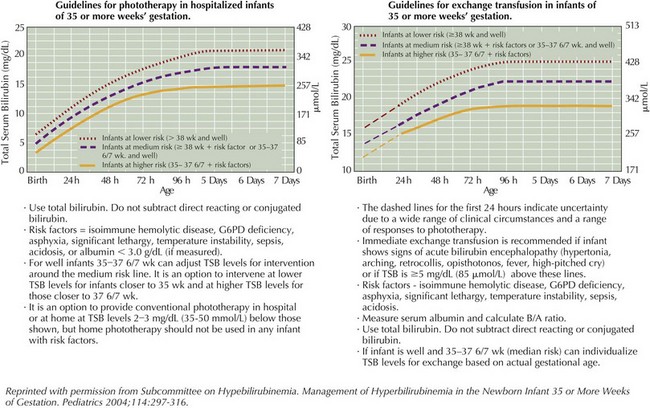

For unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, the infant’s total bilirubin level should be plotted according to hour of life on the nomogram developed by Bhutani et al. in 1999 and available in the AAP 2004 guidelines (Figure 100-4). This nomogram determines the age-specific bilirubin level at which phototherapy or exchange transfusion should be initiated in infants who are 35 weeks gestational age or greater. The treatment threshold is based on hour of life, total serum bilirubin level, and presence of additional risk factors, including gestational age, isoimmune hemolytic disease, G6PD deficiency, asphyxia, significant lethargy, unstable temperatures, acidosis, sepsis, or hypoalbuminemia. The conjugated bilirubin level should not be subtracted from the total bilirubin level when using the nomogram. However, providers should be aware of the risk of bronze baby syndrome, a usually benign discoloration of the skin that occurs in infants with cholestasis receiving phototherapy, and if conjugated bilirubin exceeds 50% of the total bilirubin in an infant requiring phototherapy, expert consultation is advised.

Based on this nomogram, phototherapy should be initiated at moderate levels of hyperbilirubinemia to aid in clearance by photoisomerizing unconjugated bilirubin into a water-soluble form that can be excreted in the bile and urine without further conjugation. Phototherapy is most effective with appropriate wavelengths of light (ideally 460–490 nm), appropriate distance and irradiance, and maximal skin exposure. Phototherapy can be toxic to the immature retina, requiring protective eye shields during treatment (Figure 100-5).

Exchange transfusion is initiated at severe levels of hyperbilirubinemia also based on the infant’s hour of life (see Figure 100-4) and in any infant exhibiting signs of acute bilirubin encephalopathy. Severe hyperbilirubinemia requiring exchange transfusion should be treated as a medical emergency and requires immediate admission to a neonatal intensive care unit for further care (see Figure 100-5). Intravenous γ-globulin may be considered in infants with isoimmune hemolytic disease who are approaching the exchange transfusion threshold.

Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

Therapy for neonatal cholestasis varies depending on the underlying cause. Sepsis requires antibiotic therapy (see Chapter 105), and inborn errors of metabolism require dietary modification or enzyme supplementation. Biliary atresia requires urgent surgical treatment because prognoses are markedly better when the Kasai procedure is performed within the first 60 days of life. In contrast, treatment of patients with many other causes focuses more on supportive care such as nutritional support with caloric and fat-soluble vitamin supplementation along with use of ursodeoxycholic acid, which aims to enhance bilirubin excretion and may reduce associated pruritus. Further management should be conducted in consultation with the appropriate specialist and is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Bhutani VK, Johnson LH, Shapiro SM. Kernicterus in sick and preterm infants (1999–2002): a need for an effective preventive approach. Semin Perinatol. 2004;28(5):319-325.

Bhutani VK, Johnson L, Sivieri EM. Predictive ability of a predischarge hour-specific serum bilirubin for subsequent significant hyperbilirubinemia in healthy term and near-term newborns. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):6-14.

Bhutani VK, Maisels MJ, Stark AR, Buonocore G, Expert Committee for Severe Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia; European Society for Pediatric Research; American Academy of Pediatrics. Management of jaundice and prevention of severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in infants >or=35 weeks gestation. Neonatology. 2008;94(1):63-67.

Ip S, Chung M, Kulig J, et al. An evidence based review of important issues concerning neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):e130-e153.

Maisels MJ, McDonagh AF. Phototherapy for neonatal jaundice. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(9):920-928.

Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):297-316.

Venigalla S, Gourley GR. Neonatal cholestasis. Semin Perinatol. 2004;28(5):348-355.