CHAPTER 186 Hydrocephalus in Children

Approach to the Patient

Recently, however, some evidence suggests that the incidence of pediatric hydrocephalus is decreasing. The number of first shunt insertions for children younger than 17 years decreased substantially in Canada between 1991 and 2000.1 The decrease may be partially related to a decline in the number of children with spina bifida. Case control studies of the effects of folic acid have shown a significant reduction in the incidence of neural tube defects, which have a high association with hydrocephalus.2 Furthermore, after a significant increase in the incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage between the 1970s and 1980s, there has been a marked decrease as experience with managing very preterm infants has grown. This too likely contributes to a decreased incidence of hydrocephalus in children.3 Societal decisions about how to treat very premature infants or those with significant malformations diagnosed in utero4 may also influence the incidence of hydrocephalus in live births.

Despite these trends, the burden of this illness remains large. Using the Healthcare Cost Utilization Project Kids’ Inpatient Database, a cross-sectional survey was performed in 1997, 2000, and 2003. Each year there were almost 40,000 admissions, approximately 400,000 hospital days, and between $1.4 billion and $2 billion in hospital charges for pediatric hydrocephalus. This accounted for 3.1% of all pediatric hospital charges. In addition, the children identified in this cross-sectional study had an increasing frequency of comorbidities.5 Clearly, pediatric hydrocephalus represents a huge burden of illness for children and is part of the daily lives of neurosurgeons in general and those treating children in particular. As a further testament to the frequency of hydrocephalus, the Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network, a newly formed cooperative clinical trial group consisting of four pediatric neurosurgical centers, accumulated almost 1000 shunt procedures in the first 8 months of data acquisition.

Presentation

The decision to treat a child with ventriculomegaly can be very difficult. Once a shunt has been implanted, it is very difficult to determine whether it can be removed. The use of adjunctive measures, such as intracranial pressure monitoring,6 magnetic resonance spectroscopy,7 and the magnetic resonance measurement of cerebral blood flow,8 has been reported in difficult cases, but the decision to treat is usually based on observation over time. Progressively increasing head size, enlarging ventricles, or progressive symptoms are the most common measures and form the most solid basis for making the decision to treat.

Disease-Specific Considerations

Congenital Hydrocephalus

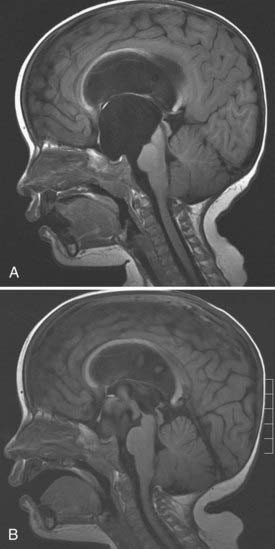

The majority of children with hydrocephalus present at or soon after birth. Many of them have aqueduct stenosis, Dandy-Walker malformation, holoprosencephaly, or other more generalized malformations of brain development. Aqueduct stenosis in males may be X-linked.9 In these children, the hydrocephalus is usually quite severe, and they have the clinical finding of adducted thumbs (Fig. 186-1). There may be other affected males in the family or a maternal history of spontaneous abortion.

Hydrocephalus Associated with Myelomeningocele

A newborn with myelomeningocele undergoes closure of the spinal defect and then observation for the development of hydrocephalus. In the past, 80% of children were thought to require ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement, but reduced rates of shunt placement have recently been reported.10 The most common manifestations of hydrocephalus in these children are increasing head circumference, splitting sutures, and full fontanelle, but some children may develop a large pseudomeningocele at the myelomeningocele repair site or a cerebrospinal fluid leak. These manifestations are often thought to be related to hydrocephalus and require the placement of a shunt. The importance of hydrocephalus in this population is emphasized by a multicenter trial funded by the National Institutes of Health that aims to randomize 200 fetuses to in utero or postnatal myelomeningocele closure. Based on suggestive preliminary data,11 the trial is testing the hypothesis that in utero closure can reduce the need for shunt placement by reducing the incidence of Chiari II malformation, the major cause of progressive hydrocephalus in this patient population.

Arachnoid Cyst

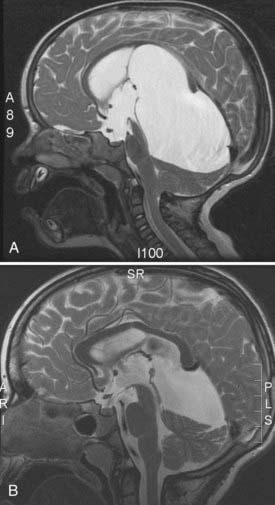

Midline and posterior fossa arachnoid cysts in newborns commonly cause obstructive hydrocephalus. These may occur in the suprasellar area (Fig. 186-2), quadrigeminal cistern (Fig. 186-3), or cerebellopontine angle. Endoscopic fenestration of the cyst rather than treating the ventricular system may relieve obstruction and reestablish normal flow.

Posthemorrhagic Hydrocephalus

Intraventricular hemorrhage in premature newborns is common and is related to the degree of prematurity and the birth weight.12 The probability of developing posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus depends on the grade of intraventricular hemorrhage. An overall 40% incidence of ventriculomegaly has been reported,13 but the incidence can be as high as 70% in patients with grade IV intraventricular hemorrhage.14 In managing these children, it should be recognized that a significant rate of arrest or resolution of this type of hydrocephalus has been reported.15 In these tiny infants, ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion can be difficult and has a high rate of complications. A number of options for delaying shunt insertion have been used, including serial lumbar punctures or treatment with furosemide (Lasix) and acetazolamide (Diamox). None of these measures has been shown to reduce the incidence of long-term hydrocephalus in randomized trials.16,17 Temporizing with either a subgaleal shunt or a ventricular reservoir until the child reaches a weight of 1500 to 2000 g is a common practice. The proportion of children who receive such a temporizing measure and go on to permanent ventriculoperitoneal shunting is approximately 70% to 90%.18 An aggressive approach to reduce hydrocephalus after premature intraventricular hemorrhage was recently attempted using drainage, irrigation, and fibrinolytic therapy. Although a promising pilot study showed a reduced requirement for shunt surgery,19 a prospective randomized trial was stopped early because of an increased rebleed rate in the treatment group.20 Despite that, the 2-year follow-up showed a reduction in death or severe disability.21

Hydrocephalus Associated with Brain Tumors

The tendency for children’s brain tumors to occur in the posterior fossa and midline leads to a high incidence of associated hydrocephalus. Management with preoperative shunt placement is no longer common practice, and most surgeons opt to remove the tumor and monitor for the development of hydrocephalus. Recently, third ventriculostomy performed before tumor removal was reported to reduce the risk of hydrocephalus significantly.22 The criticism of this approach is that some of these third ventriculostomies may be unnecessary because a proportion of children will not develop progressive hydrocephalus after tumor removal. A validated patient score for predicting the development of hydrocephalus in these children before tumor resection has been reported (Table 186-1).23 Based on age, papilledema, severity of hydrocephalus, metastatic disease, and estimated preoperative tumor type, the chance of developing hydrocephalus can now be predicted before resection of the tumor (Table 186-2). Evaluating these factors allows a more informed discussion with patients and families and possibly the selective use of endoscopic third ventriculostomy before tumor surgery. External ventricular drain insertion at the time of tumor removal is common for tumors within the fourth ventricle but may be avoided in cerebellar hemispheric tumors. Following surgery for tumors in the lateral ventricle that are associated with hydrocephalus, the surgical tract may lead to postoperative decompression of the hydrocephalus into the subdural space. When this collection persists as a subdural hygroma, it may require treatment with a subdural shunt.

TABLE 186-1 Canadian Preoperative Prediction Rule for Hydrocephalus in Children with Posterior Fossa Neoplasms

| PREDICTOR | SCORE |

|---|---|

| Age <2 yr | 3 |

| Papilledema | 1 |

| Moderate to severe hydrocephalus | 2 |

| Cerebral metastases | 3 |

| Preoperatively estimated tumor diagnosis | |

| Medulloblastoma | 1 |

| Ependymoma | 1 |

| Dorsally exophytic brainstem glioma | 1 |

| Total possible score | 10 |

From Riva-Cambrin J, Lamberti-Pasculli M, Armstrong D, et al. The validation of a preoperative prediction score for chronic hydrocephalus in pediatric patients with posterior fossa tumours. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:A798.

TABLE 186-2 Predicted Probability of Hydrocephalus Based on Canadian Preoperative Prediction Rule for Hydrocephalus Score

| PATIENT SCORE | HYDROCEPHALUS AT 6 MONTHS |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.071 |

| 1 | 0.118 |

| 2 | 0.191 |

| 3 | 0.293 |

| 4 | 0.422 |

| 5 | 0.562 |

| 6 | 0.693 |

| 7 | 0.799 |

| 8 | 0.875 |

| 9 | 0.925 |

| 10 | 0.956 |

From Riva-Cambrin J, Lamberti-Pasculli M, Armstrong D, et al. The validation of a preoperative prediction score for chronic hydrocephalus in pediatric patients with posterior fossa tumours. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:A798.

Posttraumatic Hydrocephalus

Compared with other types of hydrocephalus, posttraumatic hydrocephalus is less common in children. Affected children usually have fairly severe head injuries, and they present with a plateau or regression in their recovery. This is often identified by the rehabilitation team. The patients’ scans show ventriculomegaly, and the differential diagnosis includes hydrocephalus and ventricular enlargement ex vacuo from atrophy secondary to extensive brain injury. The use of decompressive craniectomy to treat raised intracranial pressure after head injury has been associated with a significant incidence of hydrocephalus requiring shunt placement.24

Approach to the Patient

Patients Presenting in Utero

Ventriculomegaly can be readily diagnosed in utero, and fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows the visualization of associated brain anomalies.25,26 The neurosurgeon may be asked to meet with the parents before delivery, which provides an opportunity to discuss the usual course of events after the baby is born, the indications for shunt insertion, the procedure, and potential complications. Parents naturally want to know the prognosis for their child, but unfortunately, this can be difficult to provide. In a study of patients referred to neurosurgery based on fetal ultrasound examinations, 25 of 44 patients with prenatal hydrocephalus had other anomalies, but only 3 of them were diagnosed before birth.26 Fetal MRI and ultrasonography were found to be equivalent in term of detecting fetal anomalies, with MRI usually confirming the earlier ultrasound findings.4

Patients Presenting in Infancy

Several conditions that occur in children have excess extra-axial fluid in common. These have been labeled external hydrocephalus, communicating hydrocephalus, benign extracerebral fluid collections, benign extra-axial fluid of infancy, and subdural effusion. Many of these terms were based on computed tomography findings, so it was difficult to tell whether the fluid was in the subdural or subarachnoid space, but this has been clarified using MRI.27,28 If the excess fluid is in the subarachnoid space, cortical veins can be seen stretching across the fluid signal. If the excess fluid is in the subdural space, the veins are compressed against the brain. In addition, on MRI, the subarachnoid space can be seen extending into sulci, and the subdural space can be seen as a distinct, separate layer.

Patients with excess fluid in the subarachnoid space who present as infants (commonly referred to as benign extra-axial fluid of infancy) usually have a larger than average head and normal development, except perhaps for a slight motor delay because of the large head. They do not exhibit signs of raised intracranial pressure, and as time progresses, the additional fluid usually resolves on imaging, and their future development is normal. The presence of excess fluid in the subdural space may be confused with bloody fluid occurring after trauma; to complicate matters further, it has been proposed that preexisting external hydrocephalus (with excess subarachnoid fluid) might predispose children to bleeding into the subdural space.29 This discussion often arises in the assessment of chronic subdural hematoma in infancy and whether there is a possibility of child abuse.

Older Children

Beyond infancy, both the cause of hydrocephalus and its potential management change. Congenital causes are less common in these patients, and acquired disorders are more frequent. It is in this group of children that third ventriculostomy is a more appropriate treatment option. A recent multicenter review of the Canadian experience with third ventriculostomy found that age at the time of surgery is the most important factor predicting success.30 In that study, 368 children averaging 6.5 years of age underwent third ventriculostomy. The 1- and 5-year success rates were 65% and 52%, respectively, and age was identified as the primary determinant of outcome. In patients initially treated when they were younger than 1 month, the 5-year success rate was 28%; the success rate progressively improved to 68% in patients older than 10 years.

Children with Suspected Shunt Malfunction

The likelihood of shunt failure is 40% in the first year after shunt implantation.31,32 Shunt failure can have a wide variety of presentations, but the most common mirrors a typical hydrocephalic presentation, with raised intracranial pressure, increasing head circumference, irritability, full fontanelle in a baby, and headache, nausea, and vomiting in older children. In addition, there may be fluid tracking along the shunt or fever, redness, or wound drainage in the setting of shunt infection. In evaluating a patient with possible shunt malfunction, it is helpful to remember that an individual child’s pattern of shunt failure is often similar from one occasion to another. This pattern is usually well known by the family, and their opinion about whether this represents shunt malfunction can be extremely helpful and should be sought. In the setting of multiple, recurrent shunt “malfunctions,” undiagnosed shunt infection should be considered, and cerebrospinal fluid should be sent for culture, even in the absence of fever or other signs of infection.

Children with Shunts and Chronic Headaches

A small proportion of children with hydrocephalus have recurrent headaches but lack imaging evidence of shunt malfunction. Shunt failure can certainly occur without obvious ventricular enlargement on imaging, but the physician should not jump to this conclusion, which can lead to operating on the shunt unnecessarily. Children with shunts also have all the usual reasons for headache, and tension headache and migraine should be considered in the differential diagnosis. A small number of patients do have true slit ventricle syndrome, and their management can be quite complex. Although the syndrome is not common, it results in a large number of visits and, in some cases, procedures. It may be difficult to determine whether these children have a shunt malfunction or raised intracranial pressure based on clinical assessment and imaging. In such situations, intracranial pressure monitoring may be helpful. This is preferably done without any intervention on the shunt, via a separate fiberoptic pressure monitor. Detailed discussions of the management of slit ventricle syndrome are beyond the scope of this chapter, but excellent reviews are available in the literature.33–35

Children with Shunts and Fever

The significance of fever in a child with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt depends on the timing of presentation. The vast majority of shunt infections occur within the first 3 to 6 months after an intervention (surgery or shunt tap).32 Beyond that time, shunt infection is rare unless abdominal complications have developed. Bowel perforation or abdominal pseudocysts can present years after any shunt intervention. In the absence of obvious abdominal pathology, the yield of a shunt tap more than 6 months after a procedure is very low and probably not worth the risk of introducing a new infection. Even within the first 6 months after an intervention, other sources of fever should be sought first, with a complete clinical examination and simpler cultures such as urine, sputum, and throat swabs, depending on the physical findings. If these test results are negative and the fever is persistent, a shunt tap is a reasonable option.

Long-Term Monitoring

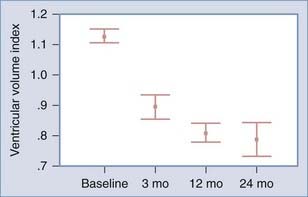

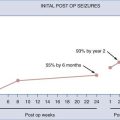

Children with shunted hydrocephalus frequently undergo regular evaluations by a neurosurgeon on an annual or biannual basis. An initial follow-up appointment after shunt surgery usually occurs within 2 or 3 months. Ventricular size may decrease over the course of the first year (Fig. 186-4), so a scan obtained at a 1-year follow-up appointment is a good basis for future comparison. Because of the high failure rate in the first year, an earlier scan at 2 or 3 months postoperatively may be worthwhile. If the child has an open fontanelle, follow-up by ultrasonography may be useful until the fontanelle closes.

Computed tomography as a method of diagnosis and follow-up has received recent attention because of concerns about radiation exposure in children.36 The use of MRI in the monitoring of shunted patients has been proposed.37 This has not been universally accepted, however, because of the demands on scanner time and the increasing use of adjustable shunt valves; these valves are susceptible to change in a magnetic field and may require readjustment after the scan. Evaluation of the valves often involves plain radiographs with radiation exposure, negating the radiation-avoiding benefits of MRI.

An argument for regular long-term imaging was based on an analysis of unexpected deaths in children with shunts.38 In that study, the death rate of children with shunts fell once regular imaging was instituted, and this was attributed to the identification of asymptomatic shunt failure.

Acakpo-Satchivi L, Shannon C, Tubbs R, et al. Death in shunted hydrocephalic children: a follow-up study. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24:197-201.

Brenner D, Hall E. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2277-2284.

Chakraborty A, Crimmins D, Hayward R, et al. Toward reducing shunt placement rates in patients with myelomeningocele. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:361-365.

Cochrane D, Kestle J. Ventricular shunting for hydrocephalus in children: patients, procedures, surgeons and institutions in English Canada, 1989-2001. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2002;12:S6-S11.

Drake J, Canadian Pediatric Neurosurgery Study Group. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy in pediatric patients: the Canadian experience. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:881-886.

Gluf W, Kestle J. “Cortical thumb sign” in X-linked hydrocephalus. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002;37:107-108.

Hill A. Ventricular dilation following intraventricular hemorrhage in the premature infant. Can J Neurol Sci. 1983;10:81-85.

Iskandar B, Sansone J, Medow J, et al. The use of quick-brain magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of shunt-treated hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:147-151.

Johnson M, Gerdes M, Rintoul N, et al. Maternal-fetal surgery for myelomeningocele: neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years of age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1145-1150.

Kan P, Amini A, Hansen K, et al. Outcomes after decompressive craniectomy for severe traumatic brain injury in children. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:337-342.

Kennedy C, Ayers S, Campbell M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of acetazolamide and furosemide in post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in infancy: follow-up at 1 year. Pediatrics. 2001;108:597-607.

Kestle JR, Drake JM, Cochrane DD, et al. Lack of benefit of endoscopic ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion: a multicenter randomized trial. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:284-290.

Kestle J, Drake J, Milner R, et al. Long-term follow-up data from the Shunt Design Trial. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2000;33:230-236.

Leliefeld P, Gooskens R, Vincken K, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for quantitative flow measurement in infants with hydrocephalus: a prospective study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;2:163-170.

Obana WG, Raskin NH, Cogen PH, et al. Antimigraine treatment for slit ventricle syndrome. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:760-763.

Riva-Cambrin J, Lamberti-Pasculli M, Armstrong D, et al. The validation of a preoperative prediction score for chronic hydrocephalus in pediatric patients with posterior fossa tumours. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:A798.

Sainte-Rose C, Cinalli G, Roux F, et al. Management of hydrocephalus in pediatric patients with posterior fossa tumors: the role of endoscopic third ventriculostomy. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:791-797.

Simon T, Riva-Cambrin J, Srivastava R, et al. Hospital care for children with hydrocephalus in the United States: utilization, charges, comorbidities, and deaths. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:131-137.

Wellons J, Shannon C, Oakes W, et al. Comparison of conversion rates from temporary CSF management to permanent shunting in premature IVH infants. In American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons Section on Pediatric Neurological Surgery. Miami Beach, FL, 2007.

Whitelaw A, Evans D, Carter M, et al. Randomized clinical trial of prevention of hydrocephalus after intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants: brain-washing versus tapping fluid. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1071-e1078.

1 Cochrane D, Kestle J. Ventricular shunting for hydrocephalus in children: patients, procedures, surgeons and institutions in English Canada, 1989-2001. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2002;12:S6-S11.

2 Pitkin R. Folate and neural tube defects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(suppl):285S-288S.

3 Fernell E, Hagberg G. Infantile hydrocephalus: declining prevalence in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:392-396.

4 Malinger G, Ben-Sira L, Lev D, et al. Fetal brain imaging: a comparison between magnetic resonance imaging and dedicated neurosonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:333-340.

5 Simon T, Riva-Cambrin J, Srivastava R, et al. Hospital care for children with hydrocephalus in the United States: utilization, charges, comorbidities, and deaths. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:131-137.

6 Fouyas I, Casey A, Thompson D, et al. Use of intracranial pressure monitoring in the management of childhood hydrocephalus and shunt-related problems. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:726-731.

7 Bluml S, McComb J, Ross B. Differentiation between cortical atrophy and hydrocephalus using 1H MRS. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37:395-403.

8 Leliefeld P, Gooskens R, Vincken K, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for quantitative flow measurement in infants with hydrocephalus: a prospective study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;2:163-170.

9 Gluf W, Kestle J. “Cortical thumb sign” in X-linked hydrocephalus. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002;37:107-108.

10 Chakraborty A, Crimmins D, Hayward R, et al. Toward reducing shunt placement rates in patients with myelomeningocele. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:361-365.

11 Johnson M, Gerdes M, Rintoul N, et al. Maternal-fetal surgery for myelomeningocele: neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years of age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1145-1150.

12 Van de Bor M, Verloove-Vanhorick S, Brand R, et al. Incidence and prediction of periventricular-intraventricular hemorrhage in very preterm infants. J Perinat Med. 1987;15:333-339.

13 Anwar M, Doyle A, Kadam S, et al. Management of posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus in the preterm infant. J Pediatr Surg. 1986;21:334-337.

14 Ahmann P, Lazzara A, Dykes F, et al. Intraventricular hemorrhage in the high-risk preterm infant. Ann Neurol. 1980;7:118-124.

15 Hill A. Ventricular dilation following intraventricular hemorrhage in the premature infant. Can J Neurol Sci. 1983;10:81-85.

16 Ventriculomegaly Trial Group. Randomised trial of early tapping in neonatal posthaemorrhagic ventricular dilatation. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65(1 Spec No):3-10.

17 Kennedy C, Ayers S, Campbell M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of acetazolamide and furosemide in post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in infancy: follow-up at 1 year. Pediatrics. 2001;108:597-607.

18 Wellons JC, Shannon CN, Kulkarni AV, et al. A multicenter retrospective comparison of conversion from temporary to permanent cerebrospinal fluid diversion in very low birth weight infants with posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4:50-55.

19 Whitelaw A, Pople I, Cherian S, et al. Phase 1 trial of prevention of hydrocephalus after intraventricular hemorrhage in newborn infants by drainage, irrigation, and fibrinolytic therapy. Pediatrics. 2003;111:759-765.

20 Whitelaw A, Evans D, Carter M, et al. Randomized clinical trial of prevention of hydrocephalus after intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants: brain-washing versus tapping fluid. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1071-e1078.

21 Whitelaw A, Jary S, Kmita G, et al. Randomized trial of drainage, irrigation and fibrinolytic therapy for premature infants with posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation: developmental outcome at 2 years. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e852-e858.

22 Sainte-Rose C, Cinalli G, Roux F, et al. Management of hydrocephalus in pediatric patients with posterior fossa tumors: the role of endoscopic third ventriculostomy. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:791-797.

23 Riva-Cambrin J, Lamberti-Pasculli M, Armstrong D, et al. The validation of a preoperative prediction score for chronic hydrocephalus in pediatric patients with posterior fossa tumours. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:A798.

24 Kan P, Amini A, Hansen K, et al. Outcomes after decompressive craniectomy for severe traumatic brain injury in children. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:337-342.

25 Limperopoulos C, Robertson R, Khwaja O, et al. How accurately does current fetal imaging identify posterior fossa anomalies? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1637-1643.

26 Schlatter D, Sanseverino M, Schmitt J, et al. Severe fetal hydrocephalus with and without neural tube defect: a comparative study. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2008;23:23-29.

27 Aoki N. Lumboperitoneal shunt: clinical applications, complications, and comparison with ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:998-1004.

28 Kuzma B, Goodman J. Differentiating external hydrocephalus from chronic subdural hematoma. Surg Neurol. 1998;50:86-88.

29 Piatt J. A pitfall in the diagnosis of child abuse: external hydrocephalus, subdural hematoma, and retinal hemorrhages. Neurosurg Focus. 1999;7:e4.

30 Drake J, Canadian Pediatric Neurosurgery Study Group. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy in pediatric patients: the Canadian experience. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:881-886.

31 Kestle JR, Drake JM, Cochrane DD, et al. Lack of benefit of endoscopic ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion: a multicenter randomized trial. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:284-290.

32 Kestle J, Drake J, Milner R, et al. Long-term follow-up data from the Shunt Design Trial. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2000;33:230-236.

33 Walker M, Fried A, Petronio J. Diagnosis and treatment of the slit ventricle syndrome. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1993;4:707-714.

34 Nowak TP, James HE. Migraine headaches in hydrocephalic children: a diagnostic dilemma. Childs Nerv Syst. 1989;5:310-314.

35 Obana WG, Raskin NH, Cogen PH, et al. Antimigraine treatment for slit ventricle syndrome. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:760-763.

36 Brenner D, Hall E. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2277-2284.

37 Iskandar B, Sansone J, Medow J, et al. The use of quick-brain magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of shunt-treated hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:147-151.

38 Acakpo-Satchivi L, Shannon C, Tubbs R, et al. Death in shunted hydrocephalic children: a follow-up study. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24:197-201.