CHAPTER 74 Hyaluronic acid injectable filler

History

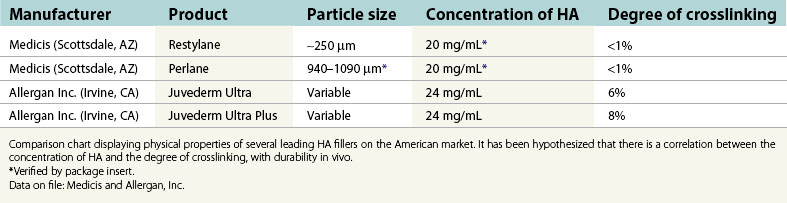

In 1996, non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) was placed on the European market under the trade name Restylane and was well received due to its increased longevity over collagen fillers. In a randomized study reported in 2003, Restylane was compared to Zyplast (bovine collagen; Inamed Aesthetics, Inc. Santa Barbara, CA.). The study indicated “superiority” of Restylane over Zyplast employing the Wrinkle Severity Rating Scale (WSRS) “at all time points and at 6 months” (Narins et al., 2003). This research also demonstrated a comparable safety profile and was instrumental for FDA approval within the United States later that year. According to a statistical analysis by the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, there were 1,593,554 HA injection procedures performed in the United States during 2006, making it the second most popular cosmetic procedure within our specialty. Currently, both NASHA as well as animal-derived HA are marketed by multiple sources throughout the world. Individual products vary in regard to particle size, concentration of HA as well as the degree of cross-linking. These attributes correlate with the product’s corrective abilities, flow characteristics, and, presumably, duration (Table 74.1).

Physical evaluation

• Possible contraindication to treatment such as uncontrolled bleeding disorders, history of keloids, relevant allergies, etc.

• The use of NSAIDs and certain herbal products may create increased bruising, and should be avoided if at all feasible.

• What are the patient’s goals and expectations?

• What are the patient’s limitations in terms of “down time”

• Can this be achieved by means of a hyaluronic acid (HA) based filler?

• Type and depth of defect (determines product placement).

• Size of defect (determines volume of product).

• Anesthesia requirements – topical, infiltration, and/or nerve block.

Anatomy

Facial aging is commonly characterized by the loss of cutaneous and subcutaneous volume. This is attributable to resorption of the facial skeleton and atrophy of subcutaneous fat. In addition, there is thinning of the dermis with pronounced elastosis and a progressive reduction of HA. These factors combine to produce the aesthetically recognizable stigmata of the aged face, such as sagging and wrinkling of the skin, as well as increased prominence of the bony landmarks and vascular structures (Fig. 74.1).

Traditionally, these anatomical changes were most commonly corrected via exclusively surgical modalities (e.g. rhytidectomy), and we truly believe the surgical facelift remains the gold standard for addressing lax and aged skin of the face. More recently, however, a “synergistic” approach addressing skin laxity and excess, as well as the loss of volume is becoming favorable. It is within this philosophy of volumetric restoration that HA fillers have found a well-defined niche. In addition, injectable therapies offer a treatment option for patients who are not candidates for, or are unwilling to undergo elective aesthetic surgery.

Technical steps

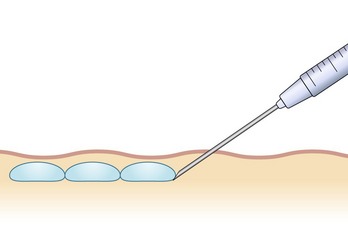

There are numerous techniques that can be used for injection of HA products. These methods vary depending upon the area being addressed, as well as the preferences of the injector. Most commonly, “serial puncture” or a “linear threading” technique are employed, especially when treating the nasolabial folds, specific rhytides or the lip border. By fully inserting the needle and injecting while it is being withdrawn, as in threading, we have the added benefit of fewer puncture sites. We often combine both methods in a “serial threading” approach, which also requires less injection points, yet allows precise placement of the filler product (Figs 74.2, 74.3). By always keeping the needle moving during injection, a smooth and predictable deposition of product is achieved.

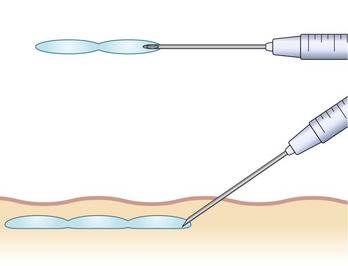

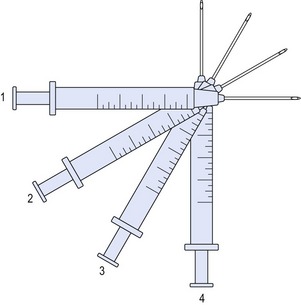

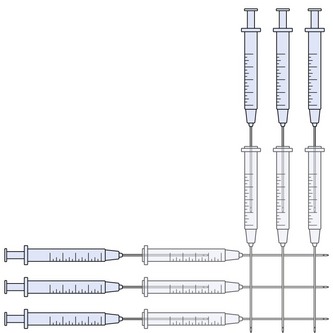

For larger flat areas such as the malar prominence or cheek, a “fanning” pattern of injection is often beneficial. As in threading, the needle is inserted fully, and the filler is extruded upon withdrawal. Prior to removal from the injection site, the trajectory is redirected in a radial pattern and repeated, not unlike the cannula movements in a suction lipectomy procedure. This configuration may be overlaid at 90 degrees, in a variation of the “cross-hatch” technique, providing volumization in a uniform manner (Figs 74.4, 74.5).

The most commonly treated areas for soft tissue augmentation with HA are the nasolabial folds, which is currently the only site specifically approved and labeled for injection by the FDA. This is also a reasonable area for the novice injector to gain experience in the use of HA fillers, as it is fairly forgiving. Correction is typically achieved with 1–3 mL injected bilaterally, depending upon severity. Often, there is a asymmetry in these folds, which must be addressed in the treatment plan in order to optimize results. Overcorrection, however, is discouraged, as it may produce an unnatural appearance which is accentuated with muscular contraction. It is of key importance that the product be placed in the deep dermis to avoid being visible and is injected slightly inferomedial to the folds themselves to prevent exacerbation of the deformity. An overlaid fanning technique works well in the superior aspects for this application, where the most volume is generally required (Figs 74.6–74.9).

Figs 74.6 & 74.7 Plan for injection of tear troughs, bilateral inframalar hollows and nasolabial folds in a 38-year-old woman who complains of volume deficiency of her face.

It is common for patients to request correction of the labiomental folds or “marionette lines” in conjunction with the nasolabial regions. Generally, 1–2 mL is sufficient volume to correct both sides. Just as with the prior techniques mentioned, the key points are to stay deep within the dermis and inferomedial to the folds. When correction is directed at the base of the folds, along the mandible the restoration of volume to the prejowl sulcus often results in a quite rejuvenating effect. It is consequently very helpful in ameliorating the appearance of a “witch’s chin”, and in certain patients may even aid in the modest redraping of submental skin.

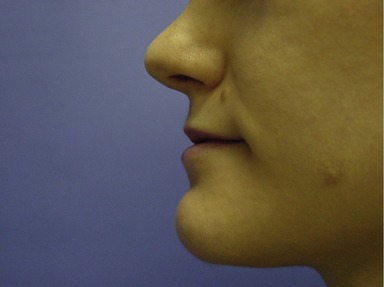

Augmentation of the lip is well achieved by injecting along the mucosal border, while volumizing the vermilion not only aids in defining the lips but also is also efficacious in minimizing the vertical rhytides commonly referred to as “smoker’s lines”. This approach is usually preferable to individual treatment of each vertical rhytid, and the lip border is an ideal area to apply one of the threading techniques discussed previously. Soft tissue augmentation of the upper lip as well as the immediately superior structures is additionally useful in reducing the aesthetic deformity of maxillary hypoplasia (Figs 74.10, 74.11). The Cupid’s bow, philtral columns and commissures are very commonly addressed, and can be modified as desired, again keeping in mind that the aesthetic ideal of the lips may have numerous interpretations (Figs 74.12–74.20).

Figs 74.14, 74.15 & 74.16 Preprocedural photos of a woman requesting lip augmentation, with a history of previous injections.

Figs 74.14, 74.15 & 74.16 Preprocedural photos of a woman requesting lip augmentation, with a history of previous injections.

Figs 74.14, 74.15 & 74.16 Preprocedural photos of a woman requesting lip augmentation, with a history of previous injections.

Figs 74.18, 74.19 & 74.20 Four weeks following procedure of lip injection. One week after injection of 1.0 mL Radiesse to bilateral nasolabial folds.

Figs 74.18, 74.19 & 74.20 Four weeks following procedure of lip injection. One week after injection of 1.0 mL Radiesse to bilateral nasolabial folds.

Figs 74.18, 74.19 & 74.20 Four weeks following procedure of lip injection. One week after injection of 1.0 mL Radiesse to bilateral nasolabial folds.

Similarly, the rhytides of the brow, glabella and “crow’s feet” are primarily associated with muscular contraction and therefore respond well to chemodenervation. Once the dynamic aspect of muscular activity has been appropriately addressed, any residual creasing of the skin may be attended to with filler materials. Again, it is important to remember that without reducing muscular contraction with Botox, the aesthetic effect may be diminished with only filler injection to the glabellar wrinkles.

The main concept to remember when treating this area is that a deeper injection is strongly recommended. This being said, several experienced practitioners have reported success injecting more superficially in multiple passes, using a 32 Ga needle to mechanically decrease particle size. Superficial placement of HA fillers, especially in areas of thin transparent skin, however, may produce irregularities as well as a Tyndall effect, which is a bluish discoloration brought about by the optical properties of HA gels. To minimize the risk of these issues the product may be placed in small parcels along the orbital rim, at the supraperiosteal level, or at least deep to the orbicularis muscle. An anterograde injection technique works well to displace vascular structures and avoid their disturbance (Figs 74.21–74.24). As most patients are unable to tolerate this procedure with only a topical anesthetic, an infraorbital nerve block incorporating epinephrine works well to provide comfort and reduce ecchymosis, which can be prolonged in the periocular region.

Figs 74.23 & 74.24 Immediately following injection of 1.2 mL of total Restylane (0.6 mL per trough).

Figs 74.23 & 74.24 Immediately following injection of 1.2 mL of total Restylane (0.6 mL per trough).

HAs work exceptionally well for “sculpting” fine detail. Discrete segments may be built up producing a very natural appearance in areas such as nasal tips, and irregularities following rhinoplasty. HA products have additionally found a successful application in the improvement of depressed scars, and subincision may be performed with the injection needle to undermine minimally adherent tissues. For more cicatricial depressions, the tip of a 22 Ga needle may be bent at 90 degrees with a sterile needle driver and inserted into the defect. By employing a reciprocal “twirling” motion the scar may be released from the underlying tissues in a rounded pattern. The treatment area may then be injected with filler material to full correction.

Postoperative care

Postprocedurally, the physician gently massages the treatment site to assess for irregularities and simultaneously corrects them by means of digital pressure. This manipulation does not denature or eliminate the material, but rather modifies the contours of the correction. Following this, a cold pack is used to minimize both swelling and the potential for bruising. Patients are instructed to apply intermittent cold compresses as often as possible, and avoid manipulation of the treatment site for the next six hours. Also, they are discouraged from engaging in any strenuous activity or consuming alcoholic beverages during this time frame to minimize vasodilatation. Typically, edema and erythema resolve in less than seven days, during which period, exposure to heat or sunlight should be deferred. A follow-up is generally scheduled for two weeks to evaluate the results and perform any “touch-ups” if required. As always, the patient is advised to contact the office prior to the next scheduled appointment if they have any questions or concerns.

Complications

The most common reactions to implantation of HAs are erythema, edema, and discomfort, which usually resolve on their own within several days. HA gels, unlike traditional collagen-based fillers, provide minimal hemostasis and are therefore more likely to result in bruising (Fig. 74.25). Liberal icing following the procedure may be of benefit in this regard. As with other procedures in aesthetic surgery, patient satisfaction is closely associated with proper patient selection, and management of expectations. It is crucial that prospective patients understand the risks, benefits and alternatives of injection with HA products, and are willing to accept the requisite down-time as well as potential complications. Preprocedural photographs should be taken for medical-legal purposes as well as to evaluate the correction upon follow-up.

HA fillers may occasionally provide suboptimal aesthetic results due to improper placement. Over correction or lumps may respond to massage, but in some cases requires extraction using an 18 Ga needle or #11 blade. Some physicians inject hyaluronidase preparations such as Vitrase (ISTA Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, CA) to dissolve excess HA material, and report variable doses of 10 to 30 U as efficacious (Matarasso et al., 2006). Please keep in mind that this is an off label use of the product and that it is ovine derived, so skin testing is advised. In general, the short-term duration of these fillers often makes patience the best intervention by far.

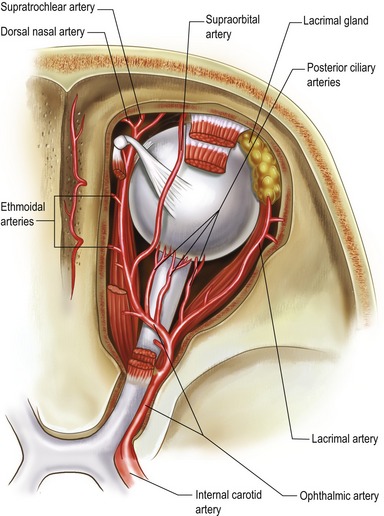

Finally, a rare but potentially devastating complication associated with dermal fillers is vascular embolization. When injecting these products with a sharp needle, it is possible to deposit material into an artery and obstruct blood flow. In severe cases, this has resulted in full thickness necrosis and loss of skin. Additionally, there have been reports of stroke and permanent loss of vision as a consequence of arterial occlusion (Coleman, 2006) (Fig. 74.26). Unfortunately, it is impossible to completely eliminate these risks when performing facial injections without forgoing treatment altogether, but keeping the needle moving during injection reduces the risk of depositing a clinically significant bolus if a vessel is entered. Also, syringe aspiration prior to injection is always advisable, especially in the periorbital area. If planning to inject in the subcutaneous tissues, a blunt cannula may be of additional benefit to avoid perforation of vessels within the subdermal plexus.

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Employ a “threading” technique to treat the inferior nasolabial folds, augment the lips or and define discrete structures such as the vermilion border and philtral columns.

• Employ a “fanning” or “cross-hatching” technique when injecting large flat areas such as the labiomental folds, superior nasolabial folds or cheeks.

• When injecting the nasolabial folds, be certain to place the material into the deep dermis, directly into the crease and slightly inferomedial to the folds themselves, to avoid accentuating the deformity.

• When injecting the superior aspect of the labiomental folds, directing the “fanning” pattern toward the vermillion border bolsters and aids in elevating the oral commissures.

• Remember to fully correct the treatment area, and lightly massage any areas of density. Overcorrection is not recommended.

Pitfalls

• Avoid overcorrection. Patients are often quite concerned about this potential, and you can always inject more product at a later session, if required.

• Avoid treating dynamic lines associated with muscular movement primarily using HA products. These are best managed via chemo-denervation (e.g. Botox), with adjuvant filler therapy as required.

• Take care not to deposit HA product as the injection needle is being withdrawn from the skin. Doing this will place the filler superficially and may lead to nodules or produce a Tyndall effect.

• Do not inject HA products too superficially in the tear trough area, in patients with thin skin, as this may produce irregularities.

• Avoid the temptation of treating patients with active cold sores or any other infections in the region. Lesions should be fully healed before any injectable therapies. The physician may wish to implement antiviral prophylaxis for patients with a history of cold sores prior to treatment.

Summary of steps

1. Patient history and physical examination is performed to rule out contraindications to treatment.

2. Risks, benefits and alternatives are discussed. All questions are answered and an informed consent is obtained.

3. Preprocedural photographs are taken.

4. A treatment plan is developed and the patient is marked in an upright position using a surgical pen if necessary.

5. Anesthesia is administered. Nerve blocks using 1% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 buffered with sodium bicarbonate 10:1 are preferable. This is injected using a 30 Ga 1-inch needle. When employing a transoral approach, topical benzocaine gel is quite helpful for numbing the mucosa.

6. The HA filler is injected using the techniques discussed to full correction.

7. The treatment area is gently pressed by the physician to assess for symmetry and smooth any areas of density.

8. A cold pack is applied to the treatment area.

9. Instructions are reviewed, including intermittent cold compresses for the following six hours. During this time, there should be no strenuous activity or manipulation of the treatment area.

10. Final assessments are made, and the patient is advised to call the office if they have any questions or concerns.

11. The patient is discharged with a follow up appointment in approximately two weeks.

American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics. www.surgery.org, 2006.

Coleman SR, the Plastic Surgery Educational Foundation DATA Committee. Hyaluronic acid fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(2):661–665.

2005 Facial Contouring with Restylane (Brochure). Medicis Aesthetics. 2005:3–55.

Matarasso SL, Carruthers JD, Jewell ML, the Restylane Consensus Group. Consensus Recommendations for soft-tissue augmentation with nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (Restylane). Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117((3) Suppl):3–34.

Narins RS, Brandt F, Leyden J, et al. A randomized, double blind, multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of Restylane versus Zyplast for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:588.

Netter FH. Atlas of human anatomy. Basel: Ciba-Geigy Corporation; 1989.

Rohrich RJ, Rios JL, Fagien S. Role of new fillers in facial rejuvenation: A cautious outlook. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(7):1899–1902.

Spinelli HM. Atlas of aesthetic eyelid and periocular surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.