CHAPTER 67 HUNTINGTON’S DISEASE

Huntington’s disease is an autosomal dominant, progressive neurodegenerative disease that typically manifests in adulthood. The prevalence is estimated at 5 to 10 per 100,000 individuals in the United States, 8 per 100,000 people in the United Kingdom, and 1 per 100,000 individuals in Japan. There is a high prevalence of Huntington’s disease, as a result of the founder effect, in several isolated populations of western European descent; these include the Lake Maracaibo region (700 per 100,000), Tasmania (17 per 100,000), and the island of Mauritius (46 per 100,000).1 The classic clinical triad of signs consists of chorea, dementia, and personality changes. Since its first description in 1872, Huntington’s disease has been identified as a trinucleotide repeat disorder and multiple treatment strategies have been attempted, but a successful cure has yet to be identified.

HISTORY

Chorea was first described in the 1600s by Paracelsus, a notable alchemist, who described a peculiar disease characterized by writhing and sporadic movements and called “St. Vitus’s Dance.” At that time it was believed to be most likely caused by mass hysteria and religious superstition. It is now thought that this “dancing mania” of epidemic proportions throughout Europe may have been caused by Huntington’s disease, epileptic seizures, or ergot poisoning. In the 1840s, for the first time, Huntington’s disease was described in the medical literature as “chronic hereditary chorea.” It was not until 1872 that George Huntington (Fig. 67-1), an American physician who was only 22 years old, submitted his famous paper “On Chorea” to The Medical and Surgical Reporter.2 His research drew from the written observations of his father and grandfather. Huntington was able to explicitly point to genetic inheritance as the mode of transmission, and he noticed that the first symptoms usually appeared at an adult age and that they were usually accompanied by mental decline as well. Because of these significant observations and conclusions, the disease bears George Huntington’s name.3 In the early 1900s, researchers first noted that the brains of Huntington’s disease patients are destroyed as the disease progresses. They identified the caudate nucleus as the central target of brain cell death. In 1955, Americo Negrette, a Venezuelan physician, published a book describing communities in Lake Maracaibo (Fig. 67-2) with unusually high numbers of individuals with chorea and reclassified their “dancing mania” as Huntington’s disease.4 More attention was brought to the disease when the famous songwriter and poet Woody Guthrie died of Huntington’s disease in 1967. Through extensive and prolonged research led by Nancy Wexler and others and the help of Lake Maracaibo residents through donation of blood samples, the gene for Huntington’s disease was finally identified in 1983 and localized in 1993.

GENETICS AND MOLECULAR PATHOGENESIS

Huntington’s disease is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by an unstable cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) repeat expansion on chromosome 4 (4p16.3) (Fig. 67-3). Affected individuals have 37 to 86 repeats, whereas normal individuals have 11 to 34 repeats. The normal protein product is termed huntingtin and serves a role in intracellular trafficking and membrane recycling.5 This CAG repeat is unstable in gametes, and the number of trinucleotide repeats can therefore change with subsequent generations. Affected fathers are more likely to transmit a higher number of repeats because of the instability of the repeat in sperm DNA. This results in a higher number of cases of juvenile Huntington’s disease in the offspring of affected fathers. This is caused by the inverse relationship between number of repeats and age at onset.6 Spontaneous mutations were once considered rare, but with DNA analysis, more cases have been revealed. About one third of individuals share a common haplotype, but the other two thirds show evidence of a spontaneous mutation in the past.7 For asymptomatic individuals with a borderline number of repeats (opinions vary, but about 34 to 37), the consequence of the genetic test results remains inconclusive.

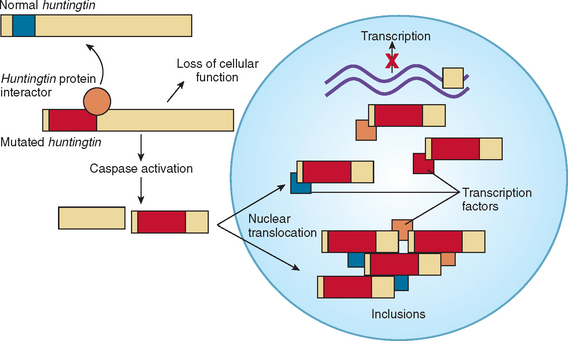

The trinucleotide CAG codes for glutamine, and the increase in the polyglutamine tract prevents normal protein turnover, thereby resulting in protein aggregation (Fig. 67-4). The aberrant protein product is ubiquitinated but fails to be efficiently degraded, which leads to the formation of intranuclear inclusions that may disrupt mitochondrial processes and other functions.8,9 The mutant huntingtin is cleaved into fragments, and these fragments may have a primary role in huntingtin toxicity, including transcriptional dysregulation.10 Mutant huntingtin associates with a rapidly growing list of proteins. These “huntingtin-interacting proteins” are involved with numerous important cell functions, including transcription, trafficking, signaling, and metabolism.11 These findings, made within 10 years after the gene for Huntington’s disease was identified, have produced much excitement. Of more importance, researchers of Huntington’s disease are identifying agents that can interfere with the pathological effect of these mechanisms. This “drug pipeline” is forming rapidly, and new clinical trials are imminent.10

CLINICAL FEATURES

The average age at onset for Huntington’s disease averages 35 to 42 years. Juvenile-onset begins before 20 years of age, and late-onset Huntington’s disease begins after the age of 50. Initial manifestations of Huntington’s disease include incoordination, occasional involuntary jerks, and difficulty with complex facial movements such as whistling or frowning. This is described as buccofacial apraxia and typically manifests before the chorea.12 Personality changes and difficulty with focusing may also manifest initially. Some affected individuals, particularly those with juvenile Huntington’s disease, never develop chorea but instead have an akinetic-rigid syndrome. Variants of Huntington’s disease are discussed later. Most cases are diagnosed on the basis of neurological symptoms, but 50% of patients develop behavioral changes or psychiatric symptoms first or concomitantly with the neurological changes.

MOTOR FEATURES

The classic neurological symptom seen in Huntington’s disease is chorea, and approximately 90% of patients are affected with it. In the beginning, the chorea may manifest only in the face or distal limbs and, over time, evolve into a more generalized form that may become dystonic. Although strength is preserved, sustained contraction may be interrupted by sudden relaxations also known as motor impersistence (“milkmaid’s grips”). Myoclonus and intention tremor occur in rare cases. The myoclonus seen is consistent with cortical reflex myoclonus.13 The classic gait of Huntington’s disease is characterized by incoordination with interrupting choreic movements. The severity of these movements can lead to the complete inability to walk and frequent falls. In early stages, affected individuals may have normal muscle tone, but over time they typically develop hypertonia of either extrapyramidal or pyramidal origins. Later in the course of the disease, individuals may develop bradykinesia and/or dystonia with or without rigidity.

Patients develop dysarthria early in the disease and dysphagia later.12 Their speech may seem slow and irregular and eventually becomes disorganized and may even deteriorate to mutism. Eye movement dysfunction is almost uniform as Huntington’s disease progresses. Typically seen is a slowing down of saccades with some dysmetria and errors with tracking and convergence.14 Swallowing usually becomes impaired, and choking is often severe enough to incur risk of death.

COGNITIVE FEATURES

The dementia of Huntington’s disease may appear before, during, or after the onset of motor symptoms. The pattern of dementia is consistent with frontal-subcortical dysfunction, with evidence of impairment in problem solving, judgment, attention, and concentration, but preservation of memory until late in the disease. All patients with Huntington’s disease eventually develop cognitive decline with an overall lowering of intelligence quotient. Through the development of standardized neuropsychometric testing, the dementia of Huntington’s disease has been further classified, and distinct patterns have been identified. Different testing batteries are applied at different centers, although typical testing includes the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised and the Halstead-Reitan Battery.12 Performances on the Controlled Word Association Test (COWAT), digit symbol test, and Stroop test commonly contain abnormalities. The pattern of dementia seen in Huntington’s disease is similar to that of the subcortical dementia of Parkinson’s disease and different from the pattern seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

PSYCHIATRIC FEATURES

Personality changes of aggressiveness, impulsiveness, emotional lability, apathy, and irritability are the most common psychiatric features in this disease and can occur in as many as 59% of patients.12 Symptoms, such as being quick to anger and depression, can be characteristic early signs. Depression is the second most common psychiatric disorder in these patients and can affect as many as 30%; the suicide rate is as high as four to six times (8 to 20 times in patients older than 50 years) that of the general population.12,15 Psychosis occurs in 6% to 25% of patients.12 This psychosis has a pattern consistent with paranoid schizophrenia and is more common in juvenile-onset Huntington’s disease.

OTHER FEATURES

Patients with Huntington’s disease may also suffer from autonomic dysfunction, including blood pressure alterations, hyperhidrosis, and bowel and bladder incontinence. Affected individuals may also have seizures, although this is more common in juvenile-onset Huntington’s disease.12 Weight loss is also common, even in patients without dysphagia, and can border on cachexia. The etiology of this is unknown, but in these patients, weight loss may be related to higher sedentary energy expenditure secondary to chorea or other involuntary muscle activity.16

VARIANTS

There are two main variants of Huntington’s disease—Westphal’s variant and juvenile-onset Huntington’s disease—and they may overlap. Westphal’s variant was first described in 1883 and is characteristically an akinetic-rigid syndrome. This variant exists in two forms; a primary form with akinetic-rigidity from onset and a secondary form with chorea preceding the akinetic-rigid state. This variant is rarely seen in the adult-onset Huntington’s disease, but it occurs in 50% of juvenile-onset cases.12

Juvenile-onset Huntington’s disease is the diagnosis given to patients with symptom onset before age 20, and it can be further subdivided into childhood onset (onset before age 10) or adolescent onset. It is estimated that 5% to 10% of individuals with Huntington’s disease have symptoms before age 20 and only 3% before age 15.12 Studies have shown that 80% of juvenile-onset Huntington’s disease cases have an affected father.17 The majority of affected individuals have rigidity and associated pyramidal features, bradykinesia, or dystonic postures. Patients with the rigid juvenile-onset Huntington’s disease have a more rapid course of disease progress than do patients with juvenile-onset Huntington’s disease or the rigid adult-onset Huntington’s disease. Juvenile-onset Huntington’s disease patients may present with the classic chorea pattern seen in adult onset. They may also evince intellectual deterioration, behavioral changes, speech and ocular dysfunction, and cerebellar signs. Interestingly, seizures can occur in up to one half of these patients, typically later in the disease course, and may be refractory to medications. The myoclonus of Huntington’s disease is more common in juvenile-onset cases and has been documented to have a cortical origin.13

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

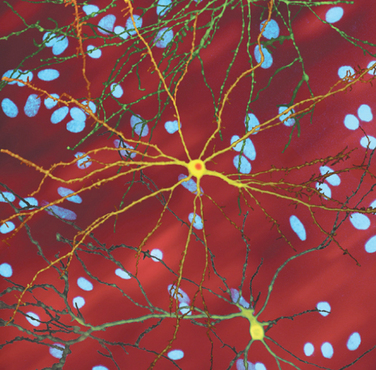

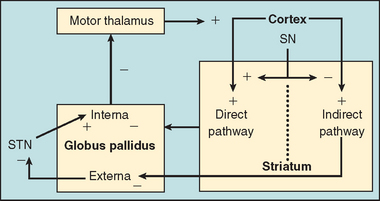

The basal ganglia, through a series of feedback loops, are important for adjusting the velocity and amplitude of movements (Fig. 67-5). In Huntington’s disease, there is selective degeneration of the neurons of the indirect pathway in the striatum, leading to an imbalance between the inhibitory and excitatory pathways.18 This imbalance in turn leads to a decrease in the cortical motor pathways’ inhibitory influences, and an exaggerated facilitation of movement (chorea) occurs. This situation seems to be the opposite of what occurs in Parkinson’s disease; therefore, medications used to treat Parkinson’s disease, such as dopaminergic and anticholinergic drugs, will worsen the chorea of Huntington’s disease.18

The pathophysiology of the cognitive changes in Huntington’s disease is still being elucidated. Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown subcortical atrophy, more so than cortical atrophy, to be correlated with cognitive dysfunction in patients with Huntington’s disease.19

Depression in Huntington’s disease can be primary or secondary. Primary depression results directly from neuronal degeneration in the caudate nucleus and its projections and can be observed early in the course of the disease.20 Secondary depression results from a disordered family environment, parental guilt for carrying the gene, or the fear of the impending devastating disease.20 One half the suicides that occur are committed by individuals with very early signs of disease who have not yet received a genetic diagnosis.15

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of Huntington’s disease may be easy if the patient has a documented family history of the disease; however, many patients who are referred for chorea lack genetic documentation. In preparing a differential diagnosis, it is important to ascertain a good medical history about childhood development, drug use or abuse, exposures, and associated neurological symptoms, as well as timing of their onset. This information can be used to help muddle through the long differential diagnosis of chorea (Table 67-1).

EVALUATION AND GENETIC TESTING

With the advent of genetic testing, the certainty of the diagnosis of Huntington’s disease was made relatively simple. The cost of the test still remains high and may be an issue for patients without insurance or those in economic hardship. Ethical issues may also arise. Therefore, it is important to consider the following question before ordering gene testing. Does the patient to be tested have symptoms of Huntington’s disease? If so, and if there is a family history, then testing is considered confirmatory; if not, but there is a family history, then this is called asymptomatic testing. In asymptomatic testing, individuals need a full neurological evaluation and genetic counseling by a trained genetic counselor before making a decision to be tested.18 If the individual is disabled by signs and symptoms of Huntington’s disease, then genetic counseling is still needed but may be performed differently because of the clinical gravity of the situation.

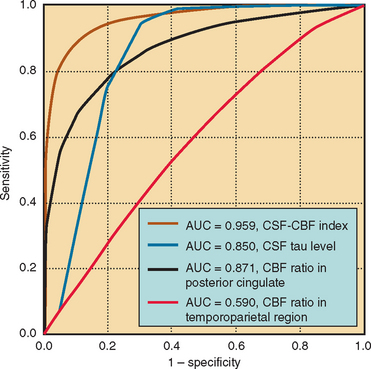

Other supplemental tests may include electroencephalography, which may show low-voltage waves, or magnetic resonance imaging, which typically reveals cortical and subcortical atrophy and significant caudate loss (butterfly ventricles) (Fig. 67-6). However, particularly early in the clinical manifestations of the disease, no computed tomographic or magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities may be detected.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

There is currently no cure for Huntington’s disease or a treatment that has slowed the neurodegenerative process. In discussing treatment options with the patient, it is important to consider possible neuroprotective agents and current treatment trials, symptom management, and physical and social supportive care (Table 67-2).

SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

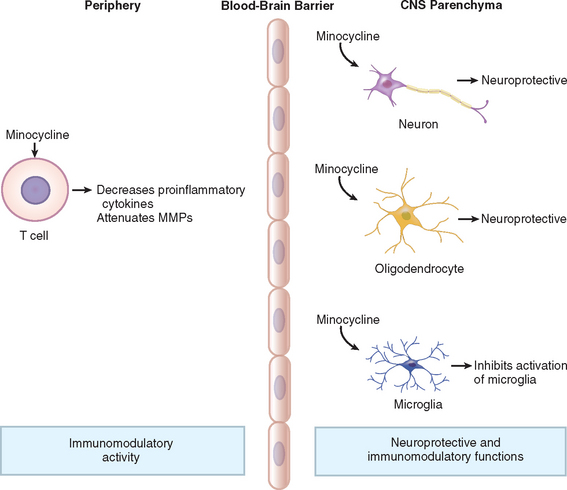

Although there have been significant advances in the elucidation of the genetics and molecular pathophysiology of Huntington’s disease, medical treatments are lagging behind. The search for a neuroprotective agent for Huntington’s disease, along with other neurodegenerative diseases, has been so far unsuccessful. Creatine, coenzyme Q10, vitamin E, and remacemide have all been tolerated by patients with Huntington’s disease but have not slowed functional decline.21–23 Higher dosages of coenzyme Q10, similar to what has yielded some preliminary success in Parkinson’s disease, await further testing. The tetracycline antibiotic minocycline, a caspase inhibitor with antiapoptotic properties, was first discovered to have neuroprotective effects in 1998 in an animal model for ischemia (Fig. 67-7).24 Since then, this medication has been studied in other diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, with some promising effects, although evidence of its benefit in the Huntington’s disease animal model has been conflicting.25 The Huntington Study Group demonstrated that minocycline is well-tolerated and safe in patients with Huntington’s disease.26 A promising 2-year pilot study showed that minocycline stabilized motor and cognitive changes while improving psychiatric symptoms.27 This study will help to motivate investigators in larger double-blind, placebo-controlled trials to evaluate the use of minocycline in Huntington’s disease further. The drug study pipeline for Huntington’s disease is providing potential new agents to be evaluated as treatment for Huntington’s disease.

The disabling chorea of Huntington’s disease is best treated with dopamine antagonists, dopamine-depleting agents, or clonazepam. However, the threshold for treating the chorea in Huntington’s disease should be higher than for other symptoms, because possible side effects include worse balance, more difficulty swallowing, and exacerbation of depression. Because dopamine antagonists can cause severe side effects, they are usually initiated after a trial of clonazepam. The dopamine antagonists most frequently used are risperidone (Risperdal), 2 to 6 mg/day; fluphenazine (Prolixin), 0.5 to 5.0 mg/day; and haloperidol (Haldol), 0.5 to 5.0 mg/day, although their use may be limited by their extrapyramidal side effects.18 Medications such as quetiapine (Seroquel), olanzapine (Zyprexa), and clozapine (Clozaril) may have less severe extrapyramidal side effects, although clozapine necessitates weekly blood evaluations and should be considered a more risky alternative than the other similar agents. Dopamine-depleting agents such as reserpine (Serapasil), 0.2 to 0.6 mg/day, and tetrabenazine (Nitoman), 50 to 200 mg/day, may also be used, although they are hard to obtain.18 No drug is currently approved in the United States for the treatment of Huntington’s disease, symptomatic or otherwise. Thus, all treatment is “off-label,” and patients and families should be informed of this. In addition, potential side effects are very real and dose limiting. For example, dopamine antagonists may cause disabling balance problems; exacerbation of depression, including suicide attempts; sedation; and tardive dyskinesia. Therefore, the indication for the treatment of involuntary movements should be strong, and follow-up is required on an ongoing basis to ensure that the benefits outweigh the side effects of these and other agents used in the treatment of Huntington’s disease.

Depression may be treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or some of the newer antidepressants, such as bupropion (Wellbutrin), venlafaxine (Effexor), or mirtazapine (Remeron).18 Mood stabilization is best treated with valproic acid (Depakote) or carbamazepine (Tegretol).18 However, stronger agents and/or neuroleptic medication may be needed. It is important to enlist the help of a psychiatrist early on in the treatment plan to better manage the psychiatric symptoms.18 At every opportunity, the risk of suicide should be openly assessed with the patient and family. If such a risk is found, then a mental health referral should be sought.

The future of treatment for Huntington’s disease may involve nondrug treatment in addition to agents that act on neurotransmitter receptors. Fetal cell transplantation, after 20 years of research, has been shown to be safe in humans, and one pilot study has indicated a possible benefit, although follow-up studies are needed.28 A promising treatment option for the disabling chorea of Huntington’s disease is deep-brain stimulation surgery, although further studies are needed.29 Laboratory studies have indicated that there may be neuroprotective effects with adenosine A1 agonists or A2A antagonists, and additional studies are under way.30

PROGNOSIS

Bonelli RM, Hofmann P. A review of the treatment options for Huntington’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:767-776.

Caviness JN. Huntington’s disease and other choreas. In: Adler CH, Ahlskog JE, editors. Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines for the Practicing Physician. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000:321-330.

Hersch SM. Huntington’s disease: prospects for neuroprotective therapy 10 years after the discovery of the causative genetic mutation. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:501-506.

Li S-H, Li X-J. Huntingtin-protein interactions and the pathogenesis of Huntington’s disease. Trends Genet. 2004;20:146-154.

1 A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Huntington’s Disease Collaboration Research Group. Cell. 1993;72:971-983.

2 Huntington G. On chorea. George Huntington, M.D. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15:109-112.

3 Okun MS. Huntington’s disease: what we learned from the original essay. Neurologist. 2003;9:175-179.

4 Okun MS. Americo Negrette (1924 to 2003): diagnosing Huntington disease in Venezuela. Neurology. 2004;63:340-343.

5 Cattaneo E, Rigamonti D, Goffredo D, et al. Loss of normal huntingtin function: new developments in Huntington’s disease research. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:182-188.

6 Fahn S. Huntington’s disease. In: Rowland LP, editor. Merritt’s Neurology. 10th ed. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:659-662.

7 Myers RH, MacDonald ME, Koroshetz WJ, et al. De novo expansion of a (CAG)(n) repeat in sporadic Huntington’s disease. Nat Genet. 1993;5:168-173.

8 DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, et al. Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science. 1997;277:1990-1993.

9 Bates G. Huntingtin aggregation and toxicity in Huntington’s disease. Lancet. 2003;361:1642-1644.

10 Hersch SM. Huntington’s disease: prospects for neuroprotective therapy 10 years after the discovery of the causative genetic mutation. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:501-506.

11 Li S-H, Li X-J. Huntingtin-protein interactions and the pathogenesis of Huntington’s disease. Trends Genet. 2004;20:146-154.

12 Haddad MS, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatry of the basal ganglia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1997;20:791-807.

13 Caviness JN, Kurth M. Cortical myoclonus in Huntington’s disease associated with an enlarged somatosensory evoked potential. Mov Disord. 1997;12:1046-1051.

14 Lasker AG, Zee DS. Ocular motor abnormalities in Huntington’s disease. Vision Res. 1997;37:3639-3645.

15 Schoenfeld M, Myers RH, Cupples LA, et al. Increased rate of suicide among patients with Huntington’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47:1283-1287.

16 Pratley RE, Salbe AD, Ravussin E, et al. Higher sedentary energy expenditure in patients with Huntington’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:64-70.

17 Martin JB, Gusella JF. Huntington’s disease: pathogenesis and management. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1267-1276.

18 Caviness JN. Huntington’s disease and other choreas. In: Adler CH, Ahlskog JE, editors. Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines for the Practicing Physician. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000:321-330.

19 Starkstein SE, Brandt J, Bylsma F, et al. Neuropsychological correlates of brain atrophy in Huntington’s disease: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:487-489.

20 Folstein SE. The psychopathology of Huntington’s disease. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;69:181-191.

21 Verbessem P, Lemiere J, Eijnde BO, et al. Creatine supplementation in Huntington’s disease: a placebo-controlled pilot trial. Neurology. 2003;61:925-930.

22 Huntington Study Group. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of coenzyme Q10 and remacemide in Huntington’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57:397-404.

23 Peyser CE, Folstein M, Chase GA, et al. Trial of D-alphatocopherol in Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1771-1775.

24 Yrjanheikki J, Keinanen R, Pellikka M, et al. Tetracyclines inhibit microglial activation and are neuroprotective in global barin ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15769-15775.

25 Smith DL, Woodman B, Mahal A, et al. Minocycline and doxycycline are not beneficial in a model of Huntington’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:186-196.

26 Huntington Study Group. Minocycline safety and tolerability in Huntington disease. Neurology. 2004;63:547-549.

27 Bonelli RM, Hodl AK, Hofmann P, et al. Neuroprotection in Huntington’s disease: a 2-year study on minocycline. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:337-342.

28 Peschanski M, Dunnett SB. Cell therapy for Huntington’s disease, the next step forward. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:81.

29 Moro E, Lang AE, Strafella AP, et al. Bilateral globus pallidus stimulation for Huntington’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:290-294.

30 Blum D, Hourez R, Galas MC, et al. Adenosine receptors and Huntington’s disease: implications for pathogenesis and therapeutics. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:366-374.