Home Care Patient Assessment

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

1. Describe the evolution and advantages of respiratory home care.

2. Explain the several major legislative and policy guidelines affecting home respiratory care.

3. Identify the type of patients who receive home respiratory care.

4. Describe the role of the respiratory therapist in home care.

5. List major tools and resources used in respiratory home care assessment.

6. Identify the key elements involved in assessing the respiratory home care patient.

7. Identify the components of the initial evaluation of the patient and home environment.

8. Describe respiratory equipment commonly used to assess and treat patients at home.

9. Review the guidelines for qualifying a patient for home oxygen therapy reimbursement.

10. Explain the purpose and the procedure for developing a plan of care.

11. Describe strategies for educating patients in the home setting.

Legislation that established Medicare in the 1960s also introduced a reimbursement structure for health care services provided in the home and at other alternative settings. More recently, the implementation of governmental policies and formal legislation has provided incentives to help successfully provide care for patients with chronic disease outside of the acute care setting. More specifically, the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey process has been adopted and implemented by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Under HCAHPS, health care providers receive financial rewards for positive outcomes, including appropriately providing care for patients at home and preventing hospital readmissions. Provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 further strengthen the implications for adherence to HCAHPS and optimizing outcomes. It is because of these provisions and other trends, including the aging population, that the number of patients receiving care at home increased to more than 10 million in 2010, this trend is likely to continue in the future.1

Many patients needing home care suffer from respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is ranked as the third most common cause of death in the United States.2,3 Patients with acute exacerbations of diseases, such as COPD, asthma, and cystic fibrosis, are initially treated in a hospital or a similar facility. However, a common goal of the care plan for such patients and the purpose of incentives under HCAHPS is to successfully treat their acute illness and discharge them to the home setting or other alternate site, and to help prevent readmission to the hospital. Not surprisingly, home care is not only cost-effective but also enhances patients’ quality of life, can have a positive influence on their psychosocial well-being, and minimizes their exposure to nosocomial infections and in-hospital hazards.

The American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC) defines respiratory home care as “prescribed respiratory services provided in a patient’s personal residence.” It should be noted that the term home care is not limited to care provided in a patient’s house, condo, or apartment and may also include other forms of personal residences, such as group homes and assisted living facilities. In addition, many of the concepts in this chapter can be applied to other alternative settings such as skilled nursing facilities. The AARC also states in regard to home care that “prescribed respiratory care services include, but are not limited to, patient assessment and monitoring, diagnostic and therapeutic modalities and services, disease management and patient and caregiver education.”4 On the surface, these services may appear to be similar to those provided in traditional acute care facilities. However, the way in which such services are performed and the resources immediately available require adjustments when applied by the respiratory therapist (RT) in a home care environment. In fact, there are many career opportunities for RTs in home care, primarily with home medical equipment (HME) companies. However, success as a home care RT not only depends on clinical competency in patient assessment and treatment but also requires strong skills related to patient education, communication, time management, ability to work independently, and resourcefulness. These and other qualifications of the RT working in home care are discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

The Evolution and Importance of Respiratory Home Care

In addition to offering the advantage of decreased medical costs, home care tends to enhance a patient’s quality of life by enabling a patient to participate in his or her own care, spend more time with loved ones and friends, and potentially avoid the need to be placed in a long-term care or similar facility. All of these advantages are particularly noteworthy in light of the projection that the number of people receiving home care services will rise to more than 12 million by 2016.5 When coupled with the fact that respiratory diseases account for the fifth largest reimbursement category under Medicare, it is expected that home care will also provide RTs with many new opportunities for the future.6 However, to successfully pursue such opportunities, RTs need to excel in many areas, including those related to assessing the patient and the environment of care, as discussed in the next sections.

The Home Care Patient

From the standpoint of such diseases, the home care RT most often sees patients with some form of a chronic lung condition. Emphysema, asthma, and chronic bronchitis are health problems the RT is likely to encounter daily. Sleep-disordered breathing, infant apnea, neuromuscular diseases, and other debilitating illnesses also are seen. Box 20-1 lists some of the most common respiratory disorders seen in home care.

Oxygen is the most common respiratory therapy modality seen in home care. A patient with an acute exacerbation of COPD may need short-term home care services designed to instruct and evaluate the patient on the use of home oxygen equipment, compressor nebulizer therapy, or a new medication schedule. Assessments should be performed to determine need, response to therapy, and compliance and to identify emergent problems that could lead to a rebound hospitalization. Goals might relate to assisting the patient in becoming independent with his or her care: to self-administer nebulizer treatments as prescribed, to use and maintain the oxygen equipment as instructed, and to know when to call the oxygen provider and how to respond to emergency situations. Once these goals are accomplished, the patient will generally be discharged from services.7

Conversely, a patient needing mechanical ventilation for life support requires home care services for as long as he or she remains at home. The technical nature of home ventilators and ancillary equipment necessitates that evaluation and maintenance be done often to ensure that they function properly. Home ventilator users also require frequent physical assessment to determine compliance with treatment and response to therapy and to identify emergent problems.8

Home Care Assessment Tools and Resources

The home care RT uses many of the methods of assessment used in the acute care setting. Several of the techniques of physical examination described earlier in this book are used in home care (see Chapters 4 and 5). Likewise, the equipment used in assessing the home care patient is also similar to that employed in the bedside evaluation of many hospitalized patients. However, the home care RT needs to become especially proficient in the use of basic equipment (e.g., stethoscope) and techniques because of the limited availability of high-tech assessment resources such as radiographic images (x-rays or computed tomography scans), bronchoscopy, serial arterial blood gases (ABGs), and complete pulmonary function testing (PFTs). In essence, the absence of such advanced resources in home care means that each assessment tool and technique available needs to be used correctly and all the results properly considered by the RT.

The tools themselves have limitations. Blood pressure measurements usually are done using a sphygmomanometer and cuff. Blood pressure measurements can be inaccurate if performed improperly. Using a cuff that is too narrow or applying the cuff too tightly results in erroneously high readings. Some automated blood pressure monitoring devices are prone to error. The RT should also take care not to press on the brachial artery too forcefully with the head of the stethoscope because this could result in erroneously high diastolic pressure readings. Some patients use self-administered blood pressure units to monitor their blood pressure. Used correctly, these units are generally accurate. However, it is fairly easy to use them incorrectly, which can give the patient inaccurate results.9 The RT should review the patient’s technique and review the manufacturer’s instructions to ensure that the equipment is being used properly. It is also useful to periodically compare an automated unit’s readings with those obtained using the RT’s blood pressure cuff. It is important for the patient to take his or her blood pressure readings at the same time each day, using the same arm, after a short rest period, and sitting in the same position each time.

Peak flowmeters are commonly used for generally stable patients at home. In fact, daily peak flow measurements are often included in asthma management programs, particularly for children.10 Reductions in peak flow readings may be a good indicator of changes in airway reactivity and patency associated with asthma. Proper technique is essential to obtain accurate readings, and the patient should be instructed to use the peak flowmeter on waking in the morning before using a bronchodilator. Each patient should have his or her own peak flowmeter; however, there is variability between models and brands, which may lead to inconsistent results.11

Pulse oximetry is also used in home care as an indicator of the adequacy of hemoglobin oxygen saturation (Spo2). It is generally considered medically unnecessary for most home care patients to have ongoing or continuous pulse oximetry monitoring, and most insurance companies will not pay for oximeters for home use. Consequently, the home care RT or nurse may simply bring a pulse oximeter unit to monitor Spo2 during periodic visits. However, a few home care patients on more sophisticated modalities, including mechanical ventilation, may have a pulse oximeter at home. In such instances, the patient or caregiver will need to be instructed on how to obtain an accurate reading and how to avoid inaccurate readings. For example, if the patient’s hands are cold, the oximetry readings could be erroneously low, or a reading may be altogether unobtainable. If the patient smokes, the readings could be erroneously high. Excessive movement, high levels of ambient light, or a low battery in the oximeter can also result in inaccurate readings. The user must understand these issues and be instructed to interpret the oximetry readings as part of a whole assessment; recommended changes should not be based on oximetry readings alone.12

Other equipment used in respiratory home care includes etco2 monitors, which can be particularly useful in patients with COPD and neuromuscular disorders. In rare instances, arterial blood sampling and analysis is performed in the home by mobile blood gas laboratories or by using point-of-service analyzers. Sputum and venous blood samples can be collected, and even electrocardiograms are occasionally obtained in the home. Once again, all of the devices used in assessing the home care respiratory patient have limitations and should be used with these issues in mind. On the other hand, the ability to properly use these tools may eliminate the need to transport the patient to a health care facility for a diagnostic procedure. More important, the ability to collect an array of clinical information often helps form a clinical picture and may warrant that the RT recommend a change to the patient’s care plan that may avoid hospitalization of the patient.13

Role and Qualifications of the Home Care Respiratory Therapist

The role of the home care RT depends in part on whether the HME company provides only HME services or also handles clinical respiratory services under The Joint Commission accreditation guidelines. The Joint Commission, formerly known as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, or JCAHO, is a private organization recognized by the federal government that surveys and evaluates more than 90% of all HME companies in the United States for accreditation. If a home care company is accredited to provide only HME services, then the RT’s role is mainly educating and ensuring safe use of home respiratory equipment such as oxygen concentrators (discussed later in this chapter). However, if the HME company also furnishes clinical respiratory services, then the RT’s function typically includes performing clinical patient assessment, testing, and administering treatment to patients at home.14 Most HME firms provide both types of services; thus, home care RTs must be qualified in both areas.

The primary role of the home care RT is to help set up respiratory equipment and train the patient and caregiver on the equipment’s safe and effective use and maintenance. The RT also monitors the patient’s overall clinical status and changes in condition as well as the patient’s response to home therapy. Several skills and qualifications are needed to fulfill this role. Foremost, a home care RT must have outstanding clinical abilities to properly assess and treat the home care patient, as well as being well versed in all respiratory therapy modalities. In applying their clinical skills, RTs must be extremely resourceful and versatile and possess good critical thinking skills because home care RTs generally perform most of their daily work functions without the presence of other clinicians. Being “on the road,” the home care RT mainly has access to the medical equipment and devices that he or she brought or that were previously delivered to the patient’s home. It is not uncommon for the job to require creative adjustments or adaptations within the realm of appropriate clinical care. Despite often operating by oneself, the home care RT must also be a team player, acting as just one important member of the patient care team and representing just one of several health disciplines responsible for devising and executing the patient care plan. Other members of the patient care team often include home health nurses; speech, physical, and occupational therapists; social workers; dietitians; home health aides; lay caregivers; and most important, the patient. Cooperation and collaboration among team members is vital to optimizing outcomes; the home care RT must also excel in communication and interpersonal skills. Communication skills, coupled with an organized approach, attention to detail, and sensitivity to cultural and age-specific considerations, are quite helpful in teaching a patient to use, maintain, and troubleshoot a complex piece of medical equipment. These same skills will also help the RT uncover changes in clinical status and promptly recommend appropriate modifications in the plan of care.15 It may be the quick recognition of, and response to, changes in a patient clinical status that can help prevent a hospital readmission, thus improving both the patient’s quality of life and the outcomes included as part of HCAHPS. In extreme situations, such as a patient whose condition has severely worsened, the RT may need to use several skills simultaneously, within the context of his or her limitations. The RT should quickly recognize the seriousness of the situation and promptly activate emergency medical services (calling 9-1-1), administer cardiopulmonary resuscitation if appropriate, and later notify other team members, including the physician.

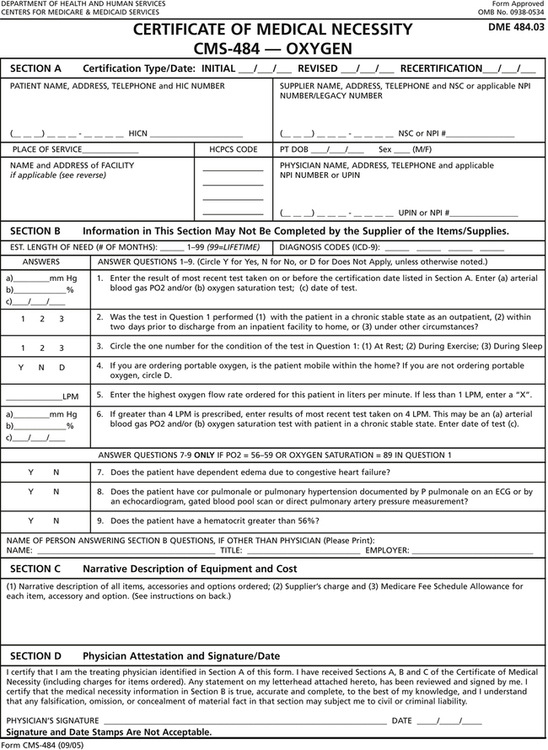

In addition, the RT should have a basic working knowledge of major guidelines, rules, and regulations pertaining to patient assessment and therapy in the home setting. Among these, the RT should have a solid understanding the AARC Clinical Practice Guidelines, especially those that pertain to patient assessment, as well as home care therapy and equipment. In addition, the RT should be familiar with certain rules and regulations set forth by the CMS. One such rule pertains to qualifying patients for home oxygen reimbursement by CMS. Under these rules, the home care patient must meet certain thresholds regarding arterial oxygen desaturation, either by pulse oximetry or ABG results, in order to be eligible for such reimbursement. Figure 20-1 is an example of a Certificate of Medical Necessity for home oxygen, whereby the physician verifies that the patient has met such threshold by completing and signing the form. It is important to note that the RT representing the home care company providing the home oxygen should not be directly involved in assessing or qualifying the patient for home oxygen reimbursement to avoid any appearance of a conflict of interest. Instead, such assessment should be performed by the prescribing physician or an RT with no affiliation with the company providing the oxygen equipment.