History taking

Introduction

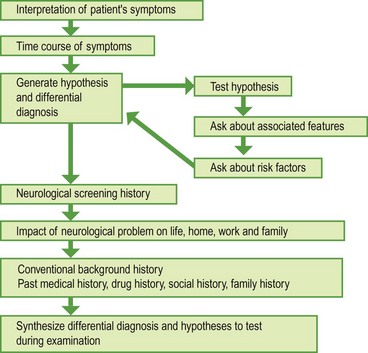

Taking a patient’s history (Fig. 1) is the most important part of the clinical assessment. The history is used to find out the nature of the neurological problem, and how it is affecting the patient. It also puts this in the context of previous medical problems, medical problems in the family, occupation and social circumstances, and other aspects of the patient’s life. The elements of a neurological history are the same as for any other subject, but because many neurological diagnoses are based solely on the history it carries greater emphasis (Box 1).

The history is usually presented in a conventional way (Box 2) so that doctors being told, or reading, the history know what they are going to be told about next. Doctors often adapt their method depending on the clinical problem with which they are faced. This section is organized in the usual way in which a history is presented, recognizing that sometimes the history can be obtained in a different order.

Presenting complaint

Frequently patients have trouble describing the feelings or sensations that they have experienced. This will require you to help interpret what they tell you – from everyday language into medical English. Patients find some sensations particularly difficult: for example, dizziness can mean light-headedness, a sensation of rotational vertigo or a feeling of being distant, among others (p. 46); the term numbness can be used by patients to mean weakness, loss of sensation or stiffness. Your knowledge of the range of symptoms that people feel will help to sort out what the patient means.

If it was of sudden onset (‘like a shutter coming down’) and resolved over 5 min, she has had amaurosis fugax (a retinal transient ischaemic attack).

If it was of sudden onset (‘like a shutter coming down’) and resolved over 5 min, she has had amaurosis fugax (a retinal transient ischaemic attack). If it developed progressively from the centre of the vision over 15 min with bright lights at the edges, resolving after 15 min followed by a headache, it was a migraine aura.

If it developed progressively from the centre of the vision over 15 min with bright lights at the edges, resolving after 15 min followed by a headache, it was a migraine aura. If there was a gradual loss of vision over 24 h with pain on eye movement and gradual recovery over 6 weeks, it was optic neuritis.

If there was a gradual loss of vision over 24 h with pain on eye movement and gradual recovery over 6 weeks, it was optic neuritis.A 60-year-old man has developed a right-sided weakness affecting his face, arm and leg:

Hypothesis testing

Asking about other symptoms that might further help to localize the cause of the symptoms. For example, a 45-year-old man has a slowly progressive weakness and stiffness in both legs and tends to trip on small steps. His symptoms suggest a bilateral upper motor neurone lesion so you should ask about (i) other symptoms of spinal cord lesions – sensory symptoms in the legs and bladder and bowel function; (ii) the upper level of the symptoms – if the arms are affected this suggests cervical cord disease, if there are brain stem symptoms then the lesion must be higher, or there is more than one lesion; (iii) other clues that might suggest the level such as back or neck pain.

Asking about other symptoms that might further help to localize the cause of the symptoms. For example, a 45-year-old man has a slowly progressive weakness and stiffness in both legs and tends to trip on small steps. His symptoms suggest a bilateral upper motor neurone lesion so you should ask about (i) other symptoms of spinal cord lesions – sensory symptoms in the legs and bladder and bowel function; (ii) the upper level of the symptoms – if the arms are affected this suggests cervical cord disease, if there are brain stem symptoms then the lesion must be higher, or there is more than one lesion; (iii) other clues that might suggest the level such as back or neck pain. Asking about other recognized symptoms of a particular clinical syndrome. For example, in a patient with suspected Parkinson’s disease, asking whether there has been any change in the writing; in suspected multiple sclerosis, asking if symptoms are worse after a bath or in hot weather.

Asking about other recognized symptoms of a particular clinical syndrome. For example, in a patient with suspected Parkinson’s disease, asking whether there has been any change in the writing; in suspected multiple sclerosis, asking if symptoms are worse after a bath or in hot weather.Common difficulties in taking a history

Too much incidental detail: ‘Do you know Gloucester at all? Well, just behind the bus station there’s a chemist …’ Gently redirect the patient to give more relevant history.

Too much incidental detail: ‘Do you know Gloucester at all? Well, just behind the bus station there’s a chemist …’ Gently redirect the patient to give more relevant history. Lists of medical contacts: ‘So I went to see my doctor, and he said … And then the specialist in Oxford thought …’ If you need to know what another doctor did or thought, contact them directly.

Lists of medical contacts: ‘So I went to see my doctor, and he said … And then the specialist in Oxford thought …’ If you need to know what another doctor did or thought, contact them directly. Forgetting everyday events: most young women taking the oral contraceptive pill do not consider this to be tablets or medicines so you have to ask directly about them.

Forgetting everyday events: most young women taking the oral contraceptive pill do not consider this to be tablets or medicines so you have to ask directly about them.Neurological screening questions

After the investigative phase of history taking, usually one asks further standard screening questions for other aspects of neurological disease (Box 3). If the hypothesis is correct this usually does not throw up any surprises.