CHAPTER 2 History of Herbal Medicines for Women

WOMEN, HERBS, AND HEALTH REFORM: A HISTORICAL SUMMARY

Such “fathers of herbal medicine” as Dioscorides did not simply pull their therapeutic theories out of the air. His herbal was the human, largely female heritage finally recorded by a man interested enough in the subject and literate enough to be able to write it down. Ironically, the early records of women’s knowledge could be read by very few women.2

—Jennifer Bennett, Lilies of the Hearth: The Historical Relationship between Women and Plants

Women’s history has always been woven with plants and the healing arts, particularly botanical medicine and midwifery. 1 2 3 4 In virtually every culture, without exception, women maintained knowledge of herbal healing for the prevention and treatment of common maladies that afflicted their communities, including herbal treatments for women’s complaints. A textbook on botanical medicine for women would not be complete without recognition of the historical role of women healers.

Few records exist to tell us the stories of ancient women healers: their training, their successes, the clinical challenges they faced, or their experiences as women with medical careers.1 The limited historical records that do exist, however, give us a glimpse of some of the remarkable women healers in ancient times. Given the pharmacy of their day, it is clear that many of these women were highly skilled herbalists.3,5 Modern history leaves no doubt as to the important role women have played in the resurgence of herbal medicine and traditional healing practices in present-day medicine.

WOMEN HEALERS THROUGHOUT HISTORY

There is a remarkable absence of women healers in the archives of medicine. Information on the practices of women healers must be “carefully teased out of a few surviving works written by women healers, from relics and artifacts, from myth and song, and from what was written about women.”1 Although women have long handed herbal knowledge down to their daughters, both orally and in the form of “stillroom” books—the herbal equivalent of family recipe books—only a minority of women from the most privileged, educated backgrounds managed to keep comprehensive records or documentation of herbal “recipes.” Negligibly few women published serious medical works. On the rare occasion one did, it was frequently under a male pseudonym. Jeanne Achterberg states:

The experience of women healers, like the experience of women in general, is a shadow throughout the record of the world that must be sought at the interface of many disciplines: history, anthropology, botany, archaeology, and the behavioral sciences. … The available information on woman as healer in the western tradition spans several thousand years, stretching far back into prehistory when conditions were likely to support women as independent and honored healers. During and following those very early years, the role of women healers has been inexorably married to shifts in the ecology, the economy, and the politics in the area in which they lived.1

Women Healers of Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece

The oldest report of a woman physician dates to circa 3000 bce. Records from this time indicate that a well-known practicing female physician lived in the city of Sais, where later there was a medical school. One of the earliest known medical documents, the Kahun papyrus (circa 1900 bce) from Egypt, addresses the diseases of women and children. It has been suggested that this papyrus was written for women practitioners, as in ancient Egypt only women treated women’s diseases.3 Egyptian queens, including Queen Hatshepsut (who reigned from 1503–1482 bce), encouraged women to become physicians. Hatshepsut herself set up three medical schools as well as botanical gardens. Women healers were responsible for planting medicinal herb gardens and maintaining pharmacies.

Egyptian belief in the afterlife led to the practice of burying with the dead those things that were important to them in life and that would be needed in their next existence. At least one Egyptian Queen, Mentuhetep, is purported to have been found buried with alabaster ointment jars, vessels for tinctured herbs, dried herbs, and spoons for measurement. Polydamna, also a queen and physician of Egypt, was reputed to have given knowledge of the healing properties of the opium poppy, one of the possible ingredients in the famous sedative nepenthe. She was also alleged to have trained Helen of Troy (circa 2000 bce), who is thought to have brought herbal knowledge from ancient Egypt to ancient Greece.3

By the time of Hippocrates (400 bce), women’s role in society had been minimized to that of servants; their role in the healing arts was likewise marginalized. Nonetheless, the contributions of several women healers were recorded. Aristotle’s wife Pythias was known to “assist” Aristotle in his work; together they wrote a text of their observations of the flora and fauna of one of the Greek islands. She was also involved in the study of anatomy and left detailed illustrations of chick and human embryologic studies. Queen Artemisia of Caria (350 bce) has been praised by Pliny the Elder and Theophrastus for her healing abilities, and is credited by them for introducing wormwood (Artemisia spp.) as a cure for numerous ailments, although there is some debate over the attribution of the botanical name for the Artemisia species to Queen Artemisia as opposed to the goddess Artemis. Pliny (c. 50 ce) wrote of several women who authored medical books, including Elephantis and Lais.3

Women Healers in Ancient Rome

Prior to Greek influence in Rome, physicians were disparaged. Families were expected to tend to their own health needs. The spiritual attributions of health and disease received more recognition than the physical, with goddesses such as Diana, Minerva, and Mater Matuta presiding over women’s reproductive concerns. Women had better social status in ancient Rome than in ancient Greece, and Roman women met the arrival of female physicians from Greece with great receptivity. It may be that Roman male rulers were less pleased. Pliny the Elder is quoted as having said that women healers should practice inconspicuously “so that after they were dead, no one would know that they have lived.”1 Nonetheless, women healers, mostly from aristocratic families, were busily practicing by the first century ce, being greatly sought after and handsomely paid for their work.

Two successful practitioners were Leoporda and Victoria, both of whom are mentioned in medical writings of the day, with Victoria receiving the dedication to a medical book. In the preface of the book, Rerum Medicarum, she is recognized as being a knowledgeable and experienced physician. Inscriptions of tombstones of women physicians from Rome include such accolades as “mistress of medical sciences” and “excellent physician.”3 Several celebrated women physicians include Olympias, Octavia, Origenia, Margareta (an army surgeon), and Fabiola. The former two wrote books of prescriptions, and the latter was considered to possess remarkable intellectual ability as well as unusual charity. Fabiola opened a hospital for the poor in Rome—the first civil hospital ever founded and thought to be one of the best in Europe at the time. It is said that when she died thousands attended her funeral procession.

Western Europe: The Middle Ages

The Middle Ages were an ambivalent time for women healers. Emerging from the early Middle Ages, during which women healers were considered to be diabolic, little respect was left for ancient traditions deifying women, their bodies, and their connection to nature. St. Jerome, ironically a dear friend and supporter of the healer Fabiola, is quoted as having said that “woman is the gate of the devil, the path of wickedness, the sting of the serpent, in a word, a perilous object.”1

By the Middle Ages, women healers appeared to take two divergent paths: Although midwives were well respected as skilled practitioners within their communities, many so-called cunning women, who were often poor and illiterate, were accused of and tried for witchcraft. Cunning women were thought to be dabbling in sorcery and bewitchment; midwives were often called as witnesses to testify against them at witchcraft trials.6 Midwives were seen as protectors of the expectant mother; a midwife was “the key figure in preventing harm…who guaranteed and subtended the order threatened by the witch.”7

Midwives were not impervious to accusations of witchcraft. There are notable cases, such as Walpurga Haussman of Dillenge, who was tried as a witch and executed.6 However, they are mainly notable because they are anomalous cases; some prosecutions were a result of political positioning, whereas others were of previously respectable midwives who slipped into “irregular healing methods.”6

Jacoba Felicie is an example of one tried for the practicing medicine without a license. Brought to trial in 1322 by the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Paris, she was a literate woman from an affluent family. Jacoba, with unspecified medical training, had successfully treated numerous patients who testified at her trial. Yet, the testimonies were used against her as proof that she had committed the cardinal crime, not of healing, but of attempting to cure. In fourteenth-century England, educated women practitioners were likewise the target of campaigns by English physicians seeking to rid themselves of “worthless and presumptuous women who usurped the profession” seeking fines and long imprisonment for women who attempted the “practyse of Fisyk.”4 Women practitioners who spared their lives had enough fear instilled in them to practice their crafts extremely covertly, if at all.

Although volumes of women’s herbal healing traditions were lost during this time, Europeans still depended on plants for medicine, so common household cures persisted. Numerous lay books on herbal medicinal cures were sold for the “gentlewoman” to use for keeping her family well, and ironically these books offered much of the same materia medica in use by physicians during that time. However, the revered place of women healers in their communities had been dramatically altered. Attitudes about nature, women, and their bodies also changed considerably, with the Baconian belief that all three were conquerable by medicine and technology.8

Trotula of Salerno is a legendary female healer of the Middle Ages. It is alleged that Trotula was considered the most distinguished teacher at the medical college in Salerno, Italy, a gathering place for men and women of Greek, Arab, Latin, and Jewish backgrounds studying medicine. She is said to have been the first female professional of medicine at Salerno, in the eleventh or twelfth century, and was called to medicine because she saw women suffering from obstetric and gynecologic complaints that they were too embarrassed to discuss with male doctors. Trotula was an early advocate of healthy diet, regular exercise, hygiene, and reduced stress. Although her history is not known with certainty, one of the most significant historical discourses on obstetrics and gynecology, referred to as The Trotula, actually a compendium of three texts, was either written in part by her, named after her, or is based on her teachings.9 The Trotula remained an authoritative text for several centuries. It is predicated on religious and philosophical notions of the period (i.e., the curse of Eve and women’s fall from grace), but the author(s) do not pathologize the normal processes of a woman’s body and assert that women have particular needs that should only be evaluated and treated by other women. The clinical portions of the book refer to the menses as “flowers,” describing menstruation as a process necessary for fertility, much as trees need flowers to produce fruits. Diagnoses are based on keen observation and include assessment of physical findings from pulse and urine, as well as the patient’s features and speech patterns. The text advanced theories and procedures, and was the first to define the diagnosis of syphilis based on its dermatologic manifestations. Trotula appears to have treated all manner of conditions with a variety of practices ranging from medicated oils to cesarean section, if necessary, with awareness of the need for antisepsis in surgery, prescribing topical and internal herbal treatments that may have been efficacious, based on what is known today about their actions. Sensitivity to the intimate needs of women is expressed, for example, by publishing the prescription of a procedure that will allow a woman who has previously lost her virginity to appear a virgin upon first intercourse after marriage, lest she face difficult political, legal, and social consequences. Jeanne Achterberg in Woman as Healer describes Trotula of Salerno:

She personified the balance that is so critical to the advancement of woman as a health care professional; a knowledge of science, attention to the magic that is embedded in the mind, a mission of service, awareness of suffering and the gift of compassion. She also had the courage to speak, write, and teach with conviction.1

The place of women healers continued to decline dramatically, but another woman healer of the Middle Ages, Hildegard of Bingen, achieved such significant fame that her story bears telling. Hildegard, like many of the other famed women healers, was born of a noble family. She lived between 1098 and 1179 ce in Germany. At 3 years of age, she began receiving visions* and she began religious education at age 8. Her gift of prophecy gave her the uncanny ability to understand religious scriptures immediately, and from an early age she drew the attention of nobles and religious leaders. She also received visions of how life at her abbey was to be lived, ranging from ornate clothing to the development of a language used in the convent—of which nearly a thousand words survive today. Hildegard was known as a gifted intellectual, skilled in both academia and the arts—the latter as a musician and composer. One of her many books, Cause et Curae, a collection of five tomes, is a comprehensive medical work in which she describes diagnosis based on four humoral types (sanguine, phlegmatic, melancholic, and choleric), reminiscent of ancient Greek medical descriptions; appropriate behaviors for lifestyle, including recommendations for diet, stress reduction, and moral behaviors; and astrological predictions, for example, for conception. She provides an extensive discourse on gynecology, with recipes for external and internal preparations, as well as applications for over 200 medicinal plants. Her recommendations also included the use of gemstones, incantations, as well as hydrotherapy.3

Women Herbalists in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

“In the year 1775 my opinion was asked concerning a family recipe for the cure of dropsy. I was told that it had long been kept a secret by an old woman in Shropshire who had sometimes made cures after the more regular practitioners had failed.”10 This statement was made by the illustrious Dr. William Withering, discussing his discovery of the use of foxglove. He is purported to have paid the woman, a Mrs. Hutton, an undisclosed sum of gold coins for sharing the family “recipe,” consisting of 20 herbs for the treatment of what was then considered a virtually incurable condition. Little mention of Mrs. Hutton or her herbal practice, if indeed that is what it was, is otherwise made, but the story of the development of the still-used drug digitalis for the treatment of congestive heart failure is medical legend.

Samuel Thomson, the founder of Thomsonian Herbalism, which for a time was rival to the “regular” doctors, wrote in 1834, “We cannot deny that women possess superior capacities for the science of medicine.”4 Thomson, like Withering, learned herbal medicine from a countrywoman well versed in the subject, although Thomson studied botanical medicines extensively, whereas Withering learned the secret of only one formula. Yet, in the Victorian era, women interested in the healing arts and plants were relegated to the study of botany, which was considered to provide good gentle exercise for the mind and body. Women were discouraged and prevented from the practice of medicine, and eventually even midwifery, the latter of which was taken over, initially by an untrained class of physicians referred to as barber surgeons, which was an accurate name as they were literally both barbers and surgeons.

Until the early 1900s, medical schools for women, blacks, and Native Americans coexisted with medical schools that allowed only males. In 1912, the Flexner report commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation, effectively led to the closure of the former schools, and only those schools sanctioned by the report remained operational.* Although many of the criticisms made in the Flexner report may have accurately portrayed the dismal state of numerous medical programs, there appears to have been no effort made after the report to ensure access to medical education for those whom these schools served.

WOMEN’s HEALTH MOVEMENTS

The Popular Health Movement

The Popular Health Movement is one of the under-acknowledged examples of a major women’s health reform movement in the United States.11 Taking place between the 1830s and 1840s, it was a broad-based social movement focused on educating individuals about their bodies, their health, and disease prevention. It was a strategic reaction against the status of the elitist, formally trained physicians who promoted heroic, dangerous treatments that were frequently as incapacitating or deadly as they might have been life saving.11 Popular health movement educators instead emphasized healthy lifestyles, proper diet, exercise, eliminating corsets, and advocated the use of birth control as well as abstinence in marriage to limit family size.

An emphasis was placed on lay practitioners, including midwives, as it was perceived that gentler treatments were to be found in the hands of women and domestic healers.11 Alternative health establishments, such as water cure centers, were popularly frequented and physiologic societies were founded that provided women opportunities to learn about and discuss their health concerns. Women were strongly encouraged to go to medical school and liberate information for others. It was firmly believed that medical information should be accessible to all and that the specialized language of doctors, medical journals, and textbooks prevented nonmedical practitioners from understanding what should rightfully be common knowledge.11

Although this movement eventually ceded to the times, the post–Civil War period marked the beginning of widening opportunities for women to access greater education. There was a significant increase in the number of women attending medical schools, with women comprising up to 6% of all physicians in the United States. This is a remarkable statistic, since as recently as 1973 in the United States, only 9% of all physicians were female.*

The Women’s Medical Movement

Women physicians, continuing the philosophic tradition of the popular health movement, established the women’s medical movement as a way to publicly challenge the popular medical philosophies regarding women’s health championed by conventional physicians. These theories included the belief that women were fragile and that education damaged the female reproductive organs. Limited by constraints that prevented them from working in male-run hospitals, they founded exemplary and successful women’s hospitals, employing doctors and nurses of both genders. Boston Women’s Medical College became the first contemporary medical school established for the training of female physicians. Eventually merging with Boston University because of financial troubles, the school still exists as the prestigious Boston University College of Medicine.

The Progressive Era

In the early 1900s, referred to as the progressive era, the women’s health movement largely wrestled with the issues of legalization of contraception, led by activist Margaret Sanger, which eventually led to the legalization of birth control and the maternal and child health movement, which was trying to increase the safety of motherhood through the establishment of prenatal care and maternal health clinics.12 New York City was the center of activity for both efforts.

ANCIENT TO MODERN HERBAL PRESCRIBING

Detailed records of the herbs used as medicines for women’s complaints have survived the centuries primarily through ancient treatises and the works of leading herbalists and physicians of their day, Soranus, Galen, Dioscorides, Rhazes, Avicenna, Trotula, Hildegard, and Gerard, among many others who published on gynecologic and obstetric herbal medicine. By the seventeenth century in England, primary health care was most commonly provided by lay people including family members, “housewyfs,” local wise women, midwives, and clergy. This led to a flood of publication of “self-help” medical books, which included information on diagnosis and treatment, the latter often largely based on herbal prescriptions, and the practice of what has been called “empirical medicine.”13 The herbal prescriptions in these books drew from the works of earlier authorities, for example, Gerard and Dioscorides, and were consistent with the standard conventional medical practices of the day, in contrast with today’s self-help or alternative health movement, whose practices often differ vastly from conventional therapies.13

Although Western herbal medicine has not enjoyed the unbroken lineage of other traditional medicine systems, for example, traditional Chinese medicine or Ayurveda, it is remarkable to observe that many of the herbs used today for gynecologic and obstetric complaints are the same as those used hundreds or thousands of years ago. There are also many obscure, even bizarre, treatments that fortunately are no longer implemented. The materia medica of Western herbal medicine has been augmented and improved by the addition of herbs that were used by the indigenous inhabitants of North America, and that have been learned by European immigrants in the 400 years since their arrival in North America.

COMMON WOMEN’s COMPLAINTS DISCUSSED IN ANCIENT TEXTS, TREATISES, AND TABLETS

The problems that have arisen in gynecologic and obstetric care historically are not entirely different from those women face today, and some conditions, such as ano-vaginal fistula, which were devastating for women 5000 years ago, remain so today for women in developing nations who lack access to proper preventative and reparative care. Box 2-1 gives a partial list representative of the types of topics that were discussed in herbals for women, although the names of conditions may have differed (e.g., amenorrhea was typically referred to as retention of menses).

COMMON HERBAL PRESCRIPTIONS FOR SELECTED WOMEN’s COMPLAINTS

This chapter is not meant to be an exhaustive accounting of all of the herbal remedies used for women’s health since time immemorial. It is meant to illustrate some of the more important remedies that were used historically, occasionally highlighting the unique or strange, and to provide a demonstration of the long historical use of herbs for women’s health. The ways in which these herbs may have been used medicinally is highly variable, and included oral administration, topical applications usually to the affected area, fumigation, douching, or as amulets and charms, or with incantations or prayers, in ancient times to one of the many goddesses or gods who presided over the health of women. Although the information presented in the following is strictly botanical, the materia medica of ancient peoples included a variety of nonherbal medicaments, for example, castoreum (musk from the perianal sacs of beavers), which was used by ancient Egyptian midwives to expedite labor, or stones such as malachite and copper salts. The primary resource for this information is The History of Medications for Women by Michael J. O’Dowd, a gem of a book for those interested in the history of medicines for women from ancient to modern times.5

Aphrodisiacs

The use of aphrodisiacs to increase libido is documented in most cultures throughout history, even as far back as ancient Assyria (Table 2-1).5 Herbal sexual stimulants remain popular products and are commonly available over the counter. Women today are most likely to seek aphrodisiac herbs for the treatment of sexual debility, such as in the perimenopausal years, rather than simply to increase an otherwise healthy sex drive.

| LOCATION | HERBS |

|---|---|

| Ancient Assyria |

Breast Abscesses/Breast Disease

Breast disease is commonly mentioned in ancient texts and treatises (Table 2-2). Although the type of breast disease is often not differentiated, it is believed that breast abscesses and breast cancer are usually the subjects. Many herbs, often in the form of poultices and washes, were used topically to treat breast disease.

| LOCATION | HERBS |

|---|---|

| Ancient Assyria |

• Chaste berry (Vitex agnus castus) extract was applied, either alone or in rose water, as a poultice for breast disorders.

|

Labor

A safe, expedient, and minimally painful labor was no less a goal of women living in ancient times than it is today. Herbs were used for all manner of problems that might have arisen during the childbearing process, from the need for pain relief to the need to augment a delayed or stopped labor. Categorically, herbs for childbearing can neatly be split into analgesics and oxytocics (Table 2-3).

| LOCATION | HERBS |

|---|---|

| Analgesics | |

| Ancient Assyria | |

| Ancient Greece and Rome | • Apples, bread, ground grain, liquid barley, melon, olive oil |

| Oxytocics | |

| Many oxytocic herbs were strong purgatives, and did not exert a direct action on the uterus, whereas others may have had a true oxytocic effect. These are mostly out of use in favor of gentler herbs or controlled pharmaceuticals. | |

| Ancient Assyria | |

| Ancient Egypt | |

Lactation

Concerns about insufficient breast milk have long plagued lactating mothers, and a number of herbs have been described for improving the quantity and quality of milk (Table 2-4). Wild lettuce (Lactuca virosa), for example, known to have grown wild in ancient Egypt, was given to women after childbirth to promote the increased flow of breast milk. It was described in 1652 by Culpepper in his herbal and in 1735 by John K’Eogh in Botanologia Universalis Hibernica as such.5 It is not used today for this purpose; it is used instead mostly as an anodyne and sedative, for which it also has been used traditionally.

| LOCATION | HERBS |

|---|---|

| Europe: Late Middle Ages | • Vervain (Verbera spp.) in lukewarm white wine |

| Ancient Egypt | • Wild lettuce (Lactuca virosa) |

Menstruation

Amenorrhea

The treatment for amenorrhea (Box 2-2), for which there were many different attributed causes, was generally in the form of emmenagogues administered orally and topically (Table 2-5). Many emmenagogues are also abortifacients, and may have been used as such. A number of these herbs may have also been used to induce uterine contractions in order to dispel a dead fetus (i.e., from miscarriage or intrauterine fetal death).

| LOCATION | HERBS |

|---|---|

| Ancient Assyria |

Dysmenorrhea

Painful menstruation commonly mentioned in ancient texts remains a common problem addressed in modern herbals for women today (Table 2-6).

| LOCATION | HERBS |

|---|---|

| Ancient Assyria |

Excessive Menstrual Bleeding

Box 2-3 includes an excerpted, translated section from an extensive protocol on uterine prolapse taken from The Trotula. Table 2-7 lists some herbs used for excessive menstrual bleeding.

| LOCATION | HERBS |

|---|---|

| Ancient Assyria |

History of American Botanical Medicine: From Thomson to the Eclectics

In the early part of the nineteenth century, medical practice in the United States was in a dismal state. General lack of medical knowledge, poor hygiene, and allopathic medicine’s adherence to dangerous treatments made going to a physician both a frightening and hazardous experience. The overuse of bleeding, mercury, arsenic, opium, emetics, and purgatives weakened patients almost as much as did the diseases.16 In response to the common practice of excessive bleeding and purging, physician William Cobbet said, “It was one of those great discoveries which are made from time to time for the depopulation of the earth.”17

Due to the “regular” doctors’ grim results with his own family and their costly fees, Samuel Thomson (1769–1843), a poorly educated New Hampshire farmer, was driven to create an herbal alternative—Thomsonian Medicine. This system borrowed heavily from Native-American herbal traditions, native sweat baths, and New England folk remedies. It was quite heroic, but substantially less toxic than the orthodox medicines commonly used.18 Thomson was a product of his times; he was strongly influenced by the individualism associated with Jacksonian Democracy.19 Upon purchasing a patent, any man or woman could become a botanic physician and practice his simple system. No further training or knowledge was needed. This simplicity is evidenced by Thomson’s primary theory “heat is life, cold is death.” Anything that increased vital heat was beneficial and anything that impeded circulation and vital force was dangerous (e.g., opium, arsenic, mercury, bleeding). The materia medica of these botanic practitioners utilized a limited number of medicines, including stimulant diaphoretics (Capsicum, Achillea millefolium, Hedeoma, Zanthoxylum americana, Zingiber officinalis), astringents (Myrica cerifera, Quercus spp., Commiphora molmol), emetics (Lobelia inflata, Eupatorium perfoliatum), sedatives (Scutellaria lateriflora, Cypripedium pubescens, Symplocarpus), and bitters (Chelone glabra, Populus tremuloides, Berberis vulgaris). Thomson’s system usually included several “courses” of steaming, purging, and sweating followed by tonification of the stomach, lungs, and bowels. Although unpleasant in its pronounced activity, this protocol was actually very successful in treating many common scourges of that time.

One of the many failings in this system was Thomson’s total aversion to further medical education; he had a profound anti-intellectual bias against a “professional class” of medical physicians. In response to Thomson’s rigidity and dictatorial nature, one of his agents and the editor of his journal, Alva Curtis (1797–1881), created his own botanic sect, which became known as the Physio-Medicalists. They founded their own sectarian medical schools and focused on the use of a large materia medica of nontoxic herbs. In addition, they developed a very complex (some would say obtuse) theoretic basis for their practice.20 Part of the Physio-Medicalist theory included an energetic diagnostic system somewhat similar to the Chinese concept of yin and yang. Patients’ constitutions and organ systems were seen as either Asthenic (hypoactive, deficient) or Sthenic (hyperactive, excess). Herbs were prescribed according to information ascertained by pulse, tongue, and other physical diagnostic procedures.

This system never developed strong support in the United States; at their height of popularity in the 1880s, they only numbered 1000 practitioners.21 Interestingly enough, this system was transplanted to England, where it flourished and was taught at the British School of Phytotherapy until the 1980s.22

By the late 1850s, the Eclectics were flourishing; Eclecticism and Homeopathy were the two primary alternatives to medical orthodoxy. This initial success of Eclectic practice was marred by constant internecine fighting, “the Eclectic resinoid craze,” and declining enrollment in the Eclectic Medical schools during the Civil War. These problems left the Eclectic Movement in serious decline by 1865.23 Resinoids—which consisted of the use of constituent resins discovered by John King, MD (1813–1893), and which included Podophyllin, Irisin, Macrotin, and Leptandrin—were stable and active resins precipitated out of liquid extracts. Unfortunately, the drug companies at that time used the same idea to produce “resinoids” from the entire materia medica only to belatedly discover these products were mostly inert. The podophyllin discovered by King is the same resin still used today in dermatology practice for the treatment of human papillomavirus (HPV).

From the depths of economic and organizational collapse, John Milton Scudder, MD (1829–1894) almost single-handedly resurrected Eclectic Medicine. In his books, Specific Medication & Specific Medicines and Specific Diagnosis, Scudder proposed a new model for practice. In this system, small doses of high-quality medicines (mostly herbal) replaced large quantities of often nauseating polyherbal or chemical preparations. Each medicine was carefully studied to find its “specific indications” in clinical practice.24 No longer were practitioners treating a disease; they now treated individual people. Each remedy was specific to the unique symptom picture the patient displayed. To further clarify the appropriate treatment, a system of differential diagnosis was developed to give the practitioner clear insights to effective prescribing. Pulse, tongue, urine, and other forms of physical diagnosis became essential tools for selecting the appropriate medicines. The major tenents of Specific Medication are:25

Specific Indications for Botanicals for Women: Eclectic Medical Tradition

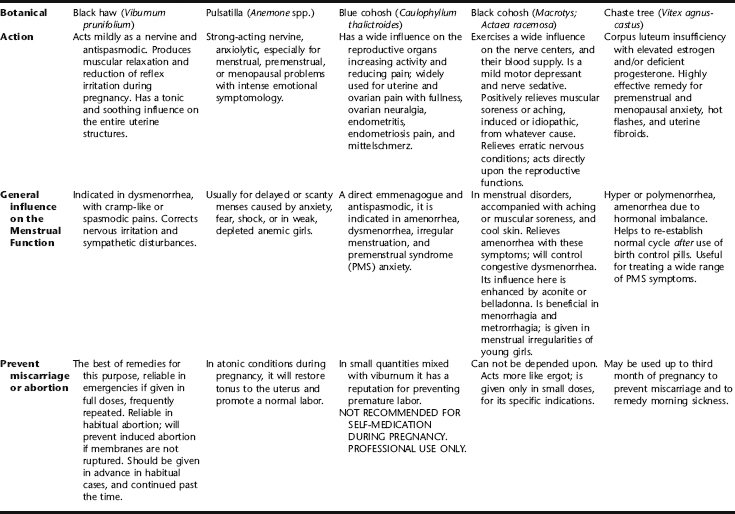

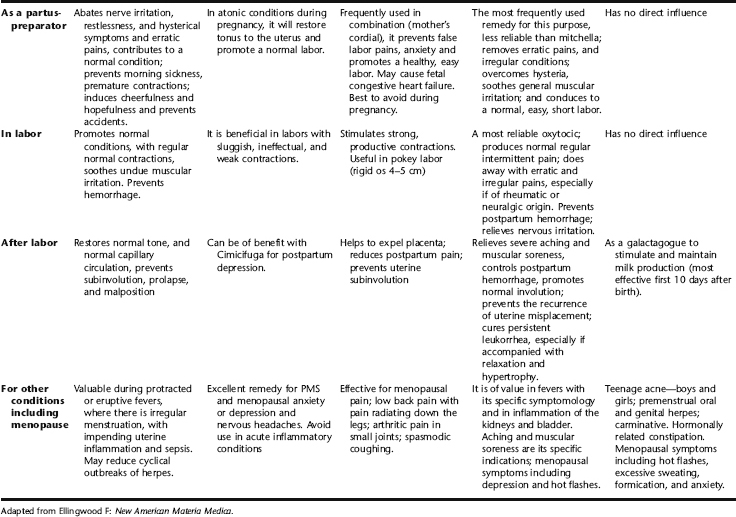

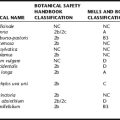

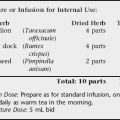

Tables 2-8 and 2-9 contain a summary and comparison of remedies acting on the reproductive organs of women that were popular among the selected medical physicians.

TABLE 2-9 Additional Female Reproductive Remedies Used by the Eclectics

| American mistletoe herb (Phoradendron serotinum) | Uterine hemorrhage, including postpartum bleeding. Used as an oxytocic to stimulate labor; considered more effective than ergot. |

| Canada fleabane herb (Conyza canadiense) | Profuse vaginal discharge or menorrhagia. |

| Cottonroot bark (Gossypium herbacium) | Clotty, scanty menses with lower backache, a feeling of fullness and weight in the pelvis and bladder. |

| Cramp bark (Viburnum opulus) | Spasmodic uterine pain–dysmenorrhea, perineal pain. |

| Helonias (Chamaelirium luteum) | Female reproductive system amphoteric, increases fertility, regulates hormonal levels. Useful for pelvic congestion. |

| Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) | Contains isoflavones (phytoestrogens)—use with white peony and saw palmetto for PCOS. |

| Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca) | Anxiolytic, antispasmodic, PMS, and menopausal anxiety. |

| Partridge berry (Mitchella repens) | Uterine astringent, menorrhagia, uterine prolapse, feeling of heaviness in abdomen, tender with pressure. |

| Peach tree bark (Prunus persica) | Irritation of the stomach and upper gastrointestinal tract—severe morning sickness. |

| Raspberry leaf (Rubus spp.) | Uterine tonic—useful throughout pregnancy and postpartum, uterine prolapse, menorrhagia. |

| Saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) | Uterine tonic—useful for PCOS, infertility, and pelvic fullness syndrome. |

| Shepherd’s purse—herb (Capsella bursa-pastoris) | Heavy bleeding caused by fibroids. |

| Thuja (Thuja occidentalis) | Used topically and orally for venereal warts resulting from human papillomavirus. Also indicated for leukorrhea and urinary dribbling. |

| Tiger lily (Lilium lancifolium) | Used for pelvic congestion and stagnation, ovarian neuralgia. |

| True unicorn rt. (Aletris farinosa) | Polymenorrhagia with labor-like pain and a sense of debility in the pelvis. |

| Water eryngo (Eryngium aquafolium) | Urinary irritation experienced as a constant sexual urge. |

| White ash bark (Fraxinus americana) | Fibroids, especially with heavy bleeding. Uterine hypertrophy with profuse leukorrhea and menstrual bleeding. |

| White baneberry root (Actea alba) | Ovarian cysts with pronounced tenderness upon palpation. |

| Yarrow herb and flower (Achillea millefolium) | Atonic menorrhagia, vaginal leukorrhea, postpartum bleeding, and heavy bleeding from fibroids. |

* The description of the physical symptoms by which Hidlegarde’s visions were accompanied is remarkably consistent with the characteristics of migraine headaches, including the prodromal or “aural” phase, through to the blinding lights and pain, and finally with the euphoric postmigraine phase. Thus, she may have been a lifelong sufferer of migraine headaches.

* Many of the medical programs, for example, Johns Hopkins University and Harvard Medical College, are among those medical colleges that continue to thrive today.

* Currently, the number of female and male medical students is approximately equal, with there often being slightly more women students than male in entering medical school classes; however, specialties such as surgery are more common to men than women.