Chapter 416 History and Physical Examination

History

Chest pain is an unusual manifestation of cardiac disease in pediatric patients, although it is a frequent cause for referral to a pediatric cardiologist, especially in adolescents. Nonetheless, a careful history, physical examination, and, if indicated, laboratory or imaging tests will assist in identifying the cause of chest pain (Table 416-1). For patients with some forms of repaired congenital heart disease or those with a history of Kawasaki disease (Chapter 438.1); however, chest pain should be evaluated carefully for a coronary etiology.

Table 416-1 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF CHEST PAIN IN PEDIATRIC PATIENTS

MUSCULOSKELETAL (COMMON)

PULMONARY (COMMON)

GASTROINTESTINAL (LESS COMMON)

CARDIAC (LESS COMMON)

IDIOPATHIC (COMMON)

OTHER (LESS COMMON)

Cardiac disease may be a manifestation of a known congenital malformation syndrome with typical physical findings (Table 416-2) or a manifestation of a generalized disorder affecting the heart and other organ systems (Table 416-3). Extracardiac malformations may be noted in 20-45% of infants with congenital heart disease. Between 5 and 10% of patients have a known chromosomal abnormality; the importance of genetic evaluation will increase as our knowledge of specific gene defects linked to congenital heart disease increases.

Table 416-2 CONGENITAL MALFORMATION SYNDROMES ASSOCIATED WITH CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

| SYNDROME | FEATURES |

|---|---|

| CHROMOSOMAL DISORDERS | |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | Endocardial cushion defect, VSD, ASD |

| Trisomy 21p (cat eye syndrome) | Miscellaneous, total anomalous pulmonary venous return |

| Trisomy 18 | VSD, ASD, PDA, coarctation of aorta, bicuspid aortic or pulmonary valve |

| Trisomy 13 | VSD, ASD, PDA, coarctation of aorta, bicuspid aortic or pulmonary valve |

| Trisomy 9 | Miscellaneous |

| XXXXY | PDA, ASD |

| Penta X | PDA, VSD |

| Triploidy | VSD, ASD, PDA |

| XO (Turner syndrome) | Bicuspid aortic valve, coarctation of aorta |

| Fragile X | Mitral valve prolapse, aortic root dilatation |

| Duplication 3q2 | Miscellaneous |

| Deletion 4p | VSD, PDA, aortic stenosis |

| Deletion 9p | Miscellaneous |

| Deletion 5p (cri du chat syndrome) | VSD, PDA, ASD |

| Deletion 10q | VSD, TOF, conotruncal lesions* |

| Deletion 13q | VSD |

| Deletion 18q | VSD |

| SYNDROME COMPLEXES | |

| CHARGE association (coloboma, heart, atresia choanae, retardation, genital, and ear anomalies) | VSD, ASD, PDA, TOF, endocardial cushion defect |

| DiGeorge sequence, CATCH 22 (cardiac defects, abnormal facies, thymic aplasia, cleft palate, and hypocalcemia) | Aortic arch anomalies, conotruncal anomalies |

| Alagille syndrome (arteriohepatic dysplasia) | Peripheral pulmonic stenosis, PS, TOF |

| VATER association (vertebral, anal, tracheo esophageal, radial, and renal anomalies) | VSD, TOF, ASD, PDA |

| FAVS (facio-auriculo-vertebral spectrum) | TOF, VSD |

| CHILD (congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma, limb defects) | Miscellaneous |

| Mulibrey nanism (muscle, liver, brain, eye) | Pericardial thickening, constrictive pericarditis |

| Asplenia syndrome | Complex cyanotic heart lesions with decreased pulmonary blood flow, transposition of great arteries, anomalous pulmonary venous return, dextrocardia, single ventricle, single atrioventricular valve |

| Polysplenia syndrome | Acyanotic lesions with increased pulmonary blood flow, azygos continuation of inferior vena cava, partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, dextrocardia, single ventricle, common atrioventricular valve |

| PHACE syndrome (posterior brain fossa anomalies, facial hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies and aortic coarctation, eye anomalies) | VSD, PDA, coarctation of aorta, arterial aneurysms |

| TERATOGENIC AGENTS | |

| Congenital rubella | PDA, peripheral pulmonic stenosis |

| Fetal hydantoin syndrome | VSD, ASD, coarctation of aorta, PDA |

| Fetal alcohol syndrome | ASD, VSD |

| Fetal valproate effects | Coarctation of aorta, hypoplastic left side of heart, aortic stenosis, pulmonary atresia, VSD |

| Maternal phenylketonuria | VSD, ASD, PDA, coarctation of aorta |

| Retinoic acid embryopathy | Conotruncal anomalies |

| OTHERS | |

| Apert syndrome | VSD |

| Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | Mitral valve prolapse |

| Carpenter syndrome | PDA |

| Conradi syndrome | VSD, PDA |

| Crouzon disease | PDA, coarctation of aorta |

| Cutis laxa | Pulmonary hypertension, pulmonic stenosis |

| de Lange syndrome | VSD |

| Ellis–van Creveld syndrome | Single atrium, VSD |

| Holt-Oram syndrome | ASD, VSD, 1st-degree heart block |

| Infant of diabetic mother | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, VSD, conotruncal anomalies |

| Kartagener syndrome | Dextrocardia |

| Meckel-Gruber syndrome | ASD, VSD |

| Noonan syndrome | Pulmonic stenosis, ASD, cardiomyopathy |

| Pallister-Hall syndrome | Endocardial cushion defect |

| Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome | VSD |

| Scimitar syndrome | Hypoplasia of right lung, anomalous pulmonary venous return to inferior vena cava |

| Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome | VSD, PDA |

| TAR syndrome (thrombocytopenia and absent radius) | ASD, TOF |

| Treacher Collins syndrome | VSD, ASD, PDA |

| Williams syndrome | Supravalvular aortic stenosis, peripheral pulmonic stenosis |

ASD, atrial septal defect; AV, aortic valve; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PS, pulmonary stenosis; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

* Conotruncal includes TOF, pulmonary atresia, truncus arteriosus, and transposition of great arteries.

Table 416-3 CARDIAC MANIFESTATIONS OF SYSTEMIC DISEASES

| SYSTEMIC DISEASE | CARDIAC COMPLICATIONS |

|---|---|

| INFLAMMATORY DISORDERS | |

| Sepsis | Hypotension, myocardial dysfunction, pericardial effusion, pulmonary hypertension |

| Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis | Pericarditis, rarely myocarditis |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Pericarditis, Libman-Sacks endocarditis, coronary arteritis, coronary atherosclerosis (with steroids), congenital heart block |

| Scleroderma | Pulmonary hypertension, myocardial fibrosis, cardiomyopathy |

| Dermatomyositis | Cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, heart block |

| Kawasaki disease | Coronary artery aneurysm and thrombosis, myocardial infarction, myocarditis, valvular insufficiency |

| Sarcoidosis | Granuloma, fibrosis, amyloidosis, biventricular hypertrophy, arrhythmias |

| Lyme disease | Arrhythmias, myocarditis |

| Löffler hypereosinophilic syndrome | Endomyocardial disease |

| INBORN ERRORS OF METABOLISM | |

| Refsum disease | Arrhythmia, sudden death |

| Hunter or Hurler syndrome | Valvular insufficiency, heart failure, hypertension |

| Fabry disease | Mitral insufficiency, coronary artery disease with myocardial infarction |

| Glycogen storage disease IIa (Pompe disease) | Short P-R interval, cardiomegaly, heart failure, arrhythmias |

| Carnitine deficiency | Heart failure, cardiomyopathy |

| Gaucher disease | Pericarditis |

| Homocystinuria | Coronary thrombosis |

| Alkaptonuria | Atherosclerosis, valvular disease |

| Morquio-Ullrich syndrome | Aortic incompetence |

| Scheie syndrome | Aortic incompetence |

| CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISORDERS | |

| Arterial calcification of infancy | Calcinosis of coronary arteries, aorta |

| Marfan syndrome | Aortic and mitral insufficiency, dissecting aortic aneurysm, mitral valve prolapse |

| Congenital contractural arachnodactyly | Mitral insufficiency or prolapse |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | Mitral valve prolapse, dilatated aortic root |

| Osteogenesis imperfecta | Aortic incompetence |

| Pseudoxanthoma elasticum | Peripheral arterial disease |

| NEUROMUSCULAR DISORDERS | |

| Friedreich ataxia | Cardiomyopathy |

| Duchenne dystrophy | Cardiomyopathy, heart failure |

| Tuberous sclerosis | Cardiac rhabdomyoma |

| Familial deafness | Occasionally arrhythmia, sudden death |

| Neurofibromatosis | Pulmonic stenosis, pheochromocytoma, coarctation of aorta |

| Riley-Day syndrome | Episodic hypertension, postural hypotension |

| Von Hippel–Lindau disease | Hemangiomas, pheochromocytomas |

| ENDOCRINE-METABOLIC DISORDERS | |

| Graves disease | Tachycardia, arrhythmias, heart failure |

| Hypothyroidism | Bradycardia, pericardial effusion, cardiomyopathy, low-voltage electrocardiogram |

| Pheochromocytoma | Hypertension, myocardial ischemia, myocardial fibrosis, cardiomyopathy |

| Carcinoid | Right-sided endocardial fibrosis |

| HEMATOLOGIC DISORDERS | |

| Sickle cell anemia | High-output heart failure, cardiomyopathy, pulmonary hypertension |

| Thalassemia major | High-output heart failure, hemochromatosis |

| Hemochromatosis (1° or 2°) | Cardiomyopathy |

| OTHERS | |

| Appetite suppressants (fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine) | Cardiac valvulopathy, pulmonary hypertension |

| Cockayne syndrome | Atherosclerosis |

| Familial dwarfism and nevi | Cardiomyopathy |

| Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome | Prolonged QT interval, sudden death |

| Kearns-Sayre syndrome | Heart block |

| LEOPARD syndrome (lentiginosis) | Pulmonic stenosis, prolonged Q-T interval |

| Progeria | Accelerated atherosclerosis |

| Osler-Weber-Rendu disease | Arteriovenous fistula (lung, liver, mucous membrane) |

| Romano-Ward syndrome | Prolonged Q-T interval, sudden death |

| Weill-Marchesani syndrome | Patent ductus arteriosus |

| Werner syndrome | Vascular sclerosis, cardiomyopathy |

LEOPARD, multiple lentigines, electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormal genitals, retardation of growth, sensorineural deafness.

General Physical Examination

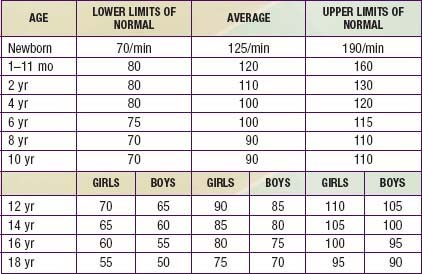

The heart rate of newborn infants is rapid and subject to wide fluctuations (Table 416-4). The average rate ranges from 120 to 140 beats/min and may increase to 170+ beats/min during crying and activity or drop to 70-90 beats/min during sleep. As the child grows older, the average pulse rate decreases and may be as low as 40 beats/min at rest in athletic adolescents. Persistent tachycardia (>200 beats/min in neonates, 150 beats/min in infants, or 120 beats/min in older children), bradycardia, or an irregular heartbeat other than sinus arrhythmia requires investigation to exclude pathologic arrhythmias (Chapter 429). Sinus arrhythmia can usually be distinguished by the rhythmic nature of the heart rate variations, occurring in concert with the respiratory cycle, and with a P wave before every QRS complex.

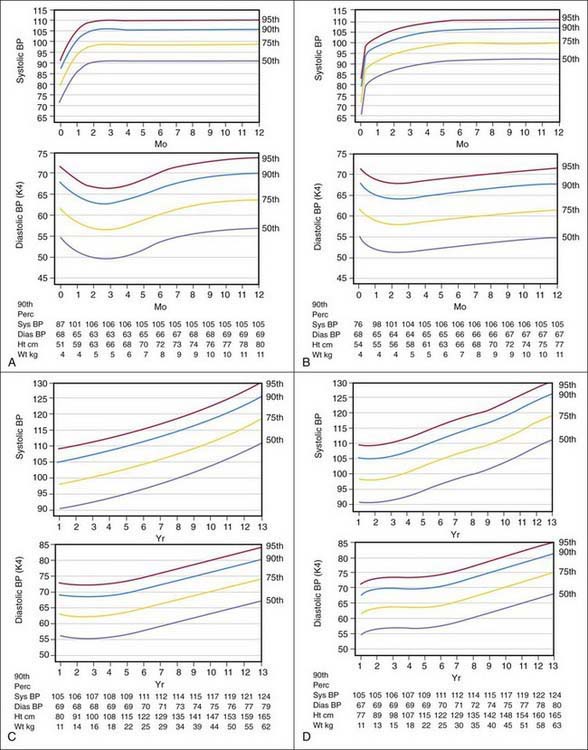

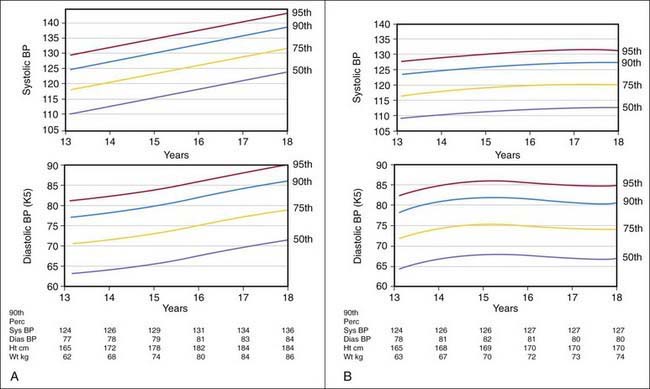

Blood pressure varies with the age of the child and is closely related to height and weight. Significant increases occur during adolescence, and many temporary variations take place before the more stable levels of adult life are attained. Exercise, excitement, coughing, crying, and struggling may raise the systolic pressure of infants and children as much as 40-50 mm Hg greater than their usual levels. Variability in blood pressure in children of approximately the same age and body build should be expected, and serial measurements should always be obtained when evaluating a patient with hypertension (Figs. 416-1 and 416-2).

Cardiac Examination

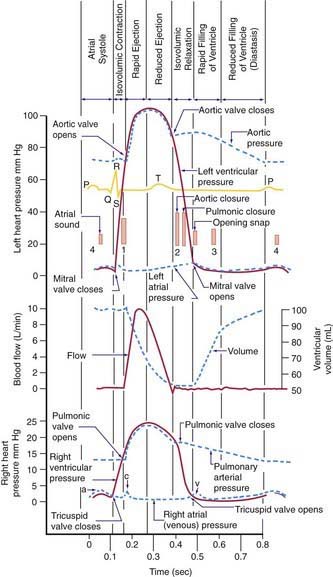

Auscultation is an art that improves with practice. The diaphragm of the stethoscope is placed firmly on the chest for high-pitched sounds; a lightly placed bell is optimal for low-pitched sounds. The physician should initially concentrate on the characteristics of the individual heart sounds and their variation with respirations and later concentrate on murmurs. The patient should be supine, lying quietly, and breathing normally. The 1st heart sound is best heard at the apex, whereas the 2nd heart sound should be evaluated at the upper left and right sternal borders. The 1st heart sound is caused by closure of the atrioventricular valves (mitral and tricuspid); the 2nd sound is caused by closure of the semilunar valves (aortic and pulmonary) (Fig. 416-3). During inspiration, the decrease in intrathoracic pressure results in increased filling of the right side of the heart, which leads to an increased right ventricular ejection time and thus delayed closure of the pulmonary valve; consequently, splitting of the 2nd heart sound increases during inspiration and decreases during expiration.

Systolic ejection murmurs start a short time after a well-heard 1st heart sound, increase in intensity, peak, and then decrease in intensity; they usually end before the 2nd sound. In patients with severe pulmonary stenosis, however, the murmur may extend beyond the 1st component of the 2nd sound, thus obscuring it. Pansystolic or holosystolic murmurs begin almost simultaneously with the 1st heart sound and continue throughout systole, on occasion becoming gradually decrescendo. It is helpful to remember that after closure of the atrioventricular valves (the 1st heart sound), a brief period occurs during which ventricular pressure increases but the semilunar valves remain closed (isovolumic contraction; see Fig. 416-3). Thus, pansystolic murmurs (heard during both isovolumic contraction and the ejection phases of systole) cannot be caused by flow across the semilunar valves because these valves are closed during isovolumic contraction. Pansystolic murmurs must therefore be related to blood exiting the contracting ventricle via either an abnormal opening (a ventricular septal defect) or atrioventricular (mitral or tricuspid) valve insufficiency. Systolic ejection murmurs usually imply increased flow or stenosis across one of the ventricular outflow tracts (aortic or pulmonic). In infants with rapid heart rates, it is often difficult to distinguish between ejection and pansystolic murmurs. If a clear and distinct 1st heart sound can be appreciated, the murmur is most likely ejection in nature.

Biancaniello T. Innocent murmurs. Circulation. 2005;111:e20-e22.

Chang RKR, Gurvitz M, Rodriguez S. Missed diagnosis of critical congenital heart disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:969-974.

Chizner MA. Cardiac auscultation: rediscovering the lost art. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2008;33:326-408.

Danduran MJ, Sheridan DC, Frommelt PC. Chest pain: characteristics of children/adolescents. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:775-781.

Kavey RE, Allada V, Daniels SR, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2006;114:2710-2738.

Mackie AS, Jutras LC, Dancea AB, et al. Can cardiologists distinguish innocent from pathologic murmurs in neoates? J Pediatr. 2009;154:50-54.

Michelfelder EC, Cnota JF. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease in an era of near-universal ultrasound screening: room for improvement. J Pediatr. 2009;155:9-10.

Pelech AN. The physiology of cardiac auscultation. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:1515-1535.

Pelech AN. The cardiac murmur. When to refer? Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45:107-122.

Rosner B, Prineas RJ, Loggie MH, et al. Blood pressure nomograms for children and adolescents, by height, sex, and age, in the United States. J Pediatr. 1993;123:871-886.

Steinberger J, Moller JH, Berry JM, et al. Echocardiographic diagnosis of heart disease in apparently healthy adolescents. Pediatrics. 2000;105:815-818.

Sun SS, Grave GD, Siervogel RM, et al. Systolic blood pressure in childhood predicts hypertension and metabolic syndrome later in life. Pediatrics. 2007;119:237-246.

Swenson JM, Fischer DR, Miller SA, et al. Are chest radiographs and electrocardiograms still valuable in evaluating new pediatric patients with heart murmurs or chest pain? Pediatrics. 1997;99:1-3.

Talner NS, Carboni MP. Chest pain in the adolescent and young adult. Cardiol Rev. 2000;8:49-56.