1.1. The history of manipulative therapy

To begin with a chapter giving a brief outline of the history of manipulative therapy is helpful for several reasons; not least because it is hard to appreciate its unique place in medicine without such an introduction. It is also important for the avoidance of mistakes and a correct appraisal of its further development.

Manipulative therapy is probably as old as the history of humankind. Throughout that history there have been healers who knew how to reposition or ‘set’ joints, including the spine. Among some peoples it was the custom for children to run barefoot over the backs of their weary parents following heavy work.

Importantly in this history, in the fifth century bc, Hippocrates, founder of European medicine, listed rachiotherapy as a further fundamental element of medicine alongside surgery and medicinal therapy. In his treatise on joints, he speaks of parathremata, a concept which corresponded to what chiropractors would recognize as slight dislocation or subluxation. Waerland expresses it in these words: ‘the vertebrae are not displaced by very much; only to a very small extent.’ Hippocrates goes on to say that ‘it is necessary to have a good knowledge of the spine, because many disorders are associated with the spine, and a knowledge of it is therefore necessary for healing a number of disorders.’ He also describes how to treat the spine: ‘This is an ancient art. I have the greatest respect for those who first discovered it, and also for their successors, whose discoveries will contribute to the further development of the art of healing in a natural way. Nothing should escape the eye and hands of the skillful physician, so that he can reposition the displaced vertebrae on the treatment table without harm to the patient. No damage can occur as long as the treatment is undertaken in the correct way.’ According to Hippocrates, the list of disorders caused by displacement of vertebrae includes pharyngitis, laryngitis, bronchial asthma, tuberculosis of the lungs, nephritis and cystitis, inadequate gonadal development, constipation, enuresis, etc.

Manipulation therapy in

ancient classical times can be seen on many reliefs. Patients would lie prone on a bed specially constructed for the purpose, while longitudinal traction to the head and legs was carried out. The physician performed manipulation of a particular vertebra. This type of therapy was evidently practiced throughout antiquity; Galen knew that the peripheral nerves emerged from the spinal cord and that they were susceptible to damage at this point, as is clear from

his account of the treatment of the Greek Sophist Pausanias.Over the course of time – particularly in the last two centuries – development took place in the primitive medicinal (herbal) therapy and the surgery of the Ancients, giving rise to modern pharmacotherapy and surgery; however, manipulation therapy continued in the same state as when the ancient classical civilizations had received it from the peoples of earlier antiquity. Consequently the successes of modern medicine completely eclipsed primitive manipulation therapy, causing it to slip to a great extent into oblivion. The medical press, which enjoys generous support from the pharmaceutical industry, contributed to this process. What we now see, therefore, is unequal development in the field of medicine, leading to a situation in which one discipline, failing to keep pace with the progress in the other specialisms, became almost forgotten. All that persisted, as far as we can tell, was a group of lay persons – to some degree established – called ‘bone setters’ who practiced manipulation therapy. This remained the situation until into the second half of the nineteenth century.

It was Andrew Taylor Still (born 1828), who practiced as a doctor in the American Civil War, who rediscovered the importance of manipulation of the spine. In 1874 he founded a school on a professional basis in Kirksville, USA, with 17 students. From the outset he also provided training to lay persons. At first the courses lasted two years; later they were extended to four years. At the present day, the length of training for a doctor of osteopathy (DO) in the United States is the same as that for medical students and permits them both to exercise their profession in general practice and to progress to specialization.

Around the year 1895, DD Palmer founded the chiropractic school in Davenport. Until then he had worked as a grocer and in magnetic healing. According to his own account, he witnessed manipulation being practiced by a physician by the name of Atkinson. Other sources say that he himself received treatment from Still. At first, the courses he provided lasted only around two weeks, and cost 500 dollars. By 1911 the courses lasted a year. At present, the training consists of four years of university-level study in the United States. Graduates obtain the title DC (doctor of chiropractic), which enables them to practice as primary care physicians.

Differences between osteopathy and chiropractic persist to this day. The training given to osteopaths in the United States endeavors to provide a complete body of medical knowledge, whereas schools of chiropractic will not teach pharmacotherapy and surgery. Among chiropractors, there is a substantial difference between those of the older and the younger generation. The older generation adheres dogmatically to the outdated theoretical and technical tradition; the younger rejects the traditional dogmas – it strives for a rational, scientific method and strongly desires to cooperate at the professional level with medical practitioners.

From the technical point of view, chiropractors confine their approach for the most part to high-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) treatment using short-lever techniques, taking very little interest in soft-tissue techniques. They are increasingly interested in rehabilitation and lifestyle (dietetics).

Osteopaths, in contrast, place emphasis on soft mobilization and soft-tissue techniques as well as HVLA treatments; however, they show a preference for long-lever techniques, using indirect (unlatching) techniques to be able to work in a targeted way. Neuromuscular techniques – muscle-energy techniques (MET) – derive from the school of Fred Mitchell, sen, Greenman and Mitchell, jun.

Although physicians in Europe initially knew little of manipulative therapy, even completely rejecting the concept, here too they gradually began to take an interest in spinal manipulation. The discovery of a mechanical disorder, the herniated intervertebral disk, was partly responsible for this interest. Attempts were made to provide relief by means of traction, and even to perform manipulation under anesthetic.

While, on the one hand, osteopaths and chiropractors were regarded as charlatans, on the other, attempts at manipulation by physicians of traditional (allopathic) medicine were rough and ready. Nevertheless, physicians in Europe were beginning to concern themselves with maneuvers applied to the spinal column. As long ago as 1903, the Swiss physician O Naegeli published his book on neurological complaints, Nervenleiden und Nervenschmerzen. Ihre Behandlung und Heilung durch Handgriffe.

Another individual deserving of mention is A Stoddard. He was originally an osteopath, and later studied medicine. His Manual of Osteopathic Techniques can be regarded as a classical textbook of manipulative techniques for the spine. The London College of Osteopathic Medicine was the first institution to provide instruction in osteopathic techniques to physicians trained in traditional medicine, and these individuals played a role in the further development that took place in Europe. The French physician, R Maigne, is one example; he also studied under the neurologist and rheumatologist, de Sèze, who was long the most influential proponent and teacher of manual medicine in France. He systematically held courses for physicians at the medical faculty in Paris and wrote textbooks. Despite the leading role played by Maigne, there are many splinter groups in France. In Britain, on the other hand, the British Institute of Musculoskeletal Medicine (BIMM, and its predecessor the BAMM) is organized in a unified way, holds courses and, under Dr Richard Ellis, publishes probably the most important medical journal in the field, International Musculoskeletal Medicine (formerly entitled the Journal of Orthopaedic Medicine).

The development that has occurred in the German-speaking countries is also of particular interest. After the end of the war, a number of German physicians began, out of necessity, to take an interest in manipulation therapy. Soon they began to found specialist scientific associations concerned both with the critical study of the issue and with courses of instruction. In Germany there were two groups involved at this time, the Forschungsgemeinschaft für Arthrologie und Chirotherapie (FAC), initially based in Hamm but later in Boppard, whose leading figures were G Gutmann, F Biedermann, A Cramer, and HD Wolff, and the Gesellschaft für manuelle Wirbelsäulen-und Extremitätengelenkstherapie (MWE) under K Sell, which was based in Neutrauchburg.

Physicians from the former German Democratic Republic of East Germany also took part in these courses up until the beginning of the 1960s. After 1961 this was no longer possible. Students of the FAC were therefore commissioned to organize courses in East Germany, which were to be on the same lines as the FAC, and at the Charité in Berlin, under Professor H Krauss and K Lewit from Prague. This task was more than could be done by just one person, so it was necessary to train instructors who would later take over the leadership of the Association. The most important of these were E Kubis, J Sachse, K Schildt-Rutlow, and H Tlustek. After the reunification of Germany this group became established as the Ärzteseminar Berlin (ÄMM).

Today the FAC, MWE and ÄMM together make up the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Manuelle Medizin (DGMM).

The development in former Czechoslovakia is also of great interest, as a result of the profoundly different political situation and especially in view of the fundamental role it served as a model for other then-communist countries (including East Germany). At the end of 1951 the Ministry of Health commissioned the university hospitals to undertake a review of the methods used by lay practitioners and practitioners of complementary medicine. To this end a chiropractor with a practice in Prague was reviewed at the neurological clinic (under Professor Henner). It was an ideal moment, when interest was focused on the intervertebral disk problem, and also on exploring the feasibility of reflex therapy. An additional factor there was the position of neurology in Czechoslovakia in Professor Henner’s time: there was an interest in problems of pain and the locomotor system, and neurology also had a leading role in the development of rehabilitation.

This made it possible for the technique of manipulation therapy to be reviewed in a clinical domain. Later there came the provision of instruction too, emanating from a prominent university hospital and later also provided by the Institute of Postgraduate Medical Training (under Professor Z Macek). Instruction was given in the form of a series of three two-week courses. Later, physiotherapists began increasingly to be trained in neuromuscular mobilization techniques. This is done in association with their university training.

This model was then taken up in East Germany, Poland, the former Soviet Union, and to some extent in Hungary and Bulgaria.

A professional body whose name refers merely to a method is not entirely satisfactory to physicians, however, given that the object concerned is the locomotor system and especially its dysfunctions. A number of bodies therefore decided to reinterpret the initials FIMM to represent the name Fédération Internationale de Médecine Musculosquelettale (International Federation for Musculoskeletal Medicine).

Despite considerable activity in scientific work, manipulation has continued to be regarded by a great number of traditional physicians as an outsider’s method; dysfunctions are little understood and, in matters at the practical level, physicians find it difficult to keep pace with physiotherapists, osteopaths, and chiropractors.

1.2. Fundamental principles of reflex therapy

Pain – both in general and in disorders of the locomotor system – is a curse that humanity has always suffered. The constant search for relief has led to a great range of treatments of all kinds. The traditional approach has regarded bed rest and – to an extent and with some reserve – pharmacotherapy as the only reliable answer. From another standpoint there are many other methods that belong mainly, although not exclusively, to the realm of physical therapy, and these all have their eager proponents. These include massage, various kinds of electrotherapy, laser and magnet therapies, acupuncture, neural therapy, manipulation, local cold or hot applications, cupping, wheal therapy, remedial exercise, and movement therapy. The common feature of all these methods is their reflex effect.

We may ask why, when treating essentially the same disorders, preference is given sometimes to one method and sometimes to another. This sometimes gives the impression that the choice of method depends on which treatment the practitioner is best able to perform, irrespective of actual suitability.

The pathomechanism underlying most of these methods is the reflex effect; they act on sensory receptors to produce a reflex response in the region where the pain originates. They can therefore be termed methods of reflex therapy. We must next ask which receptors are activated and which structures they supply.

The route by which the control by the nervous system operates is primarily that of reflex reaction; it would be helpful to proceed from this to an understanding of where, how, and why we should apply one or the other method. The better we comprehend the various methods, the more effective the treatment we can deliver. Since these methods are most frequently applied in painful conditions, there follows a description of nociceptive (pain) stimulation.

1.2.1. Nociceptive stimulation

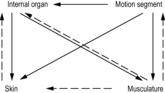

Any localized

pain stimulation begins by provoking a

reflex in the segment to which the stimulated structure belongs. In this segment we usually find a hyperalgesic zone (HAZ) in the skin, muscle hardening, trigger points (TrPs), painful periosteal points, movement restriction of the corresponding segment of the spinal column, and (perhaps) some dysfunction of a visceral organ (see

Figure 1.1). This enables us to diagnose the changes present and use whichever method is appropriate to exert an effect on the skin, soft tissues, muscles, periosteum, motion segment of the spinal column, or visceral organ involved. Working in this way and on a case by case basis, we can decide in each case which structure is the location of the most intense changes, and which is the probable source of the pain.

These reflex changes are not confined to a single motion segment. For example, visceral disturbances are accompanied by viscerovisceral reflexes: pain in the region of the gall bladder produces nausea; pain in the region of the heart produces a sense of oppression, etc.

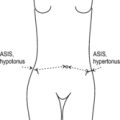

This kind of effect is still more strikingly seen in the locomotor system: an acute disturbance in one segment of the spinal column produces muscle spasm in substantial sections of the erector spinae; any local movement restriction produces effects in distant segments of the spinal column, after the manner of a chain reaction. Any serious lesion at the periphery also brings about a central response: the motor pattern, or stereotype, will change in order to spare the affected structure. In this way altered patterns of movement are formed, and can sometimes persist after the peripheral lesion has disappeared (see

Figure 1.2).

Reflex relations between the periphery and the central nervous system

Pain stimuli produce both somatic and autonomic responses at all levels. The somatic response to the stimulus consists mainly of muscle hardening or the opposite response of hypotension (inhibition of the muscle). The expression of pain is found in the form of trigger points both in hypertonic muscles and in (otherwise) hypotonic ones.

The autonomic response takes the form of reactions in HAZs and soft tissues, and of a vasomotor reaction (mainly vasoconstriction) within the segment. At the level of the central nervous system, these reactions may occur as stress affecting respiration, the cardiovascular or the digestive system. At this level there can also be changes in motor patterns, the stereotypes of muscle action.

Once we know the source of nociceptive stimulation, for example movement restriction of a spinal segment, and can assess its severity, then the intensity of these reflex changes can provide information about the reaction of the patient and of the particular segment. We can use the subjective assessment of the pain to evaluate the nociceptive stimulus, the reflex reaction, and the central (psychological) susceptibility of the patient to pain.

These somewhat schematic guidelines indicate some possible lines of action to take in painful disorders, using essentially the same approach as a neurologist would employ in disturbances of mobility. This approach is essential if we are to act in a targeted way, that is if we are to know why, when, and where we should use one or other of the methods of reflex therapy. First, therefore, we need to distinguish the source of pain and the reflex effects in the segment, at the suprasegmental level and at the level of the central nervous system.

As a rule a nociceptive stimulus produces somatic and autonomic changes. It is necessary to understand these changes in order to arrive at a rational, targeted course of treatment.

The key to this difficult task lies in the functions, or the dysfunctions, of the locomotor system. Since this subject is the main theme of the present book, no more need be said at this stage than to point out that the locomotor system is by far the most frequent source of pain in the body. This is readily understandable, because not only does the locomotor system constitute about three-quarters of our body weight, but it is under the control of our will – consequently even at the mercy of our whims – and has no other way of protecting itself against misuse than by causing pain. First and foremost, then, pain warns us of harmful function or malfunction. Conversely dysfunction is the most common cause of pain originating in the locomotor system.

1.3. Reflex therapy

1.3.1. Indications and methods

Clearly the chosen therapy and method must depend on the structure upon which we wish to act. In our approach to the skin, for example, a great variety of methods are available, as the receptors in the skin are easy to access (e.g. by massage, electrotherapy, wheal therapy, or simple skin stretching).

Muscle hardness (myogelosis; TrP) can be treated by massage, and more effectively by post-isometric relaxation (PIR), reciprocal inhibition (RI), pressure and needling.

Manipulation and mobilization are mainly used to treat functional, reversible movement restrictions of joints or segments of the spinal column.

Painful periosteal points can be treated by massage, soft tissue techniques, needling, or, if they are the insertion points of muscles, by PIR and RI of the muscles concerned.

The most appropriate treatment for disturbed motor patterns is remedial exercise.

1.3.2. Choice of method

The next step is to decide which of the affected structures is most important and which less so; which change is probably primary and which secondary. The severity of the disturbance is also significant. Even at the segmental level, there is a kind of hierarchy: in general, visceral disorders and abnormal motor patterns tend to be primary. The significance of disturbances in muscles, joints, and soft tissues can only be decided based on an analysis of the pathogenesis. The particular importance of the fasciae and active scars should be emphasized in this connection.

In the locomotor system and in the spinal column, there are regions of greater and of lesser importance. There are some sections in which primary lesions occur more frequently than in others. It is vital to recognize those faulty motor patterns which are regularly found to cause relapses if left untreated.

In this connection psychological factors play a major part, because motor patterns are in part expressions of the state of mind: anxiety, depression, and an inability to relax exert a considerable influence on motor function; no less important is the subject’s psychological attitude to pain, since pain is the most frequent symptom in our patients.

In addition to issues of pathogenesis, there are certain practical aspects of technique to be considered, since not all methods are equally effective or ‘economical.’ For example, needling or soft-tissue techniques are usually more economical for the treatment of periosteal pain points than periosteal massage, but wherever possible (i.e. if the periosteal point is a point of muscle insertion) we prefer to use PIR with RI of the muscle, because these techniques are painless and usually suitable for self-treatment. The attractiveness of manipulation techniques lies mainly in the fact that they are effective and quick to perform.

We can see from this that there is a wide range of possible treatments from which to select the most suitable. The decision as to which to use is reached by making as accurate a diagnosis as possible of the individual changes, and from this make what is known as the ‘

present relevance’

diagnosis – what

Gutmann (1975) calls the

pathogenetische Aktualitätsdiagnose. This aims to identify the change that is the most important link in the chain of pathology at a given moment.

All too frequently methods are applied which, for example, stimulate the skin when no signs of a HAZ have been found, or relax a muscle when no tension has been diagnosed (no TrPs found); we even find manipulations being performed when no restriction was present. Clearly, too, it is a waste of time to prescribe remedial exercise when there is no diagnosis of faulty muscle control.

Naturally, in order to produce an accurate ‘present relevance’ diagnosis of pathogenesis as explained above, we need to have identified the

individual links in the chain of pathology and analyzed their significance. We must proceed in a systematic fashion, starting at the peripheral level and working up to the central, applying treatment according to our findings.

The ‘present relevance’ diagnosis according to Gutmann enables us to identify the most significant link in the chain of pathogenesis.

Nevertheless, at times the results of treatment fail to meet expectations. One of the reasons for this is the presence of a lesion which causes intense nociceptive stimulation and dominates the clinical picture without the patient being aware of it. This may be referred to as a field of disturbance. Most commonly the source of this is an ‘active scar,’ the expression of which is a HAZ, increased resistance to shifting, and, in the abdominal cavity, a resistance that is tender on examination. If the usual methods of therapy are unsuccessful, it is essential to treat the scar. Another cause of repeated failure is masked depression. This should always be considered in patients presenting with chronic pain, and needs to be treated.

The dysfunctions of the locomotor system that are described here, together with the reflex changes they produce, may aptly be called the ‘functional pathology of the locomotor system.’

1.3.3. Structural and functional changes

In this connection the unfortunate but frequent use of the term ‘functional’ as a euphemism for ‘psychological’ is most regrettable – it implies a grave underestimation of the importance of function and its role in pathogenesis. In rehabilitation we are primarily concerned with function, and seek at the very least to improve it when dealing with conditions where there is underlying pathomorphological, structural change. This is readily understandable; dysfunction is the form in which any relevant structural lesion is clinically expressed. It is fundamentally important to distinguish structural disturbances from functional ones.

Where the disturbance is functional, it would be a mistake to think of the dysfunction as being exclusively a matter of reflex changes and reflex control. What we are dealing with here is more than just ‘reflexes’; these are rather ‘programs,’ having memory and capable of being elicited. They affect the entire locomotor system and its disturbances.

The most common disturbances, which are also the object of manipulation therapy, concern the spinal column. The term ‘vertebrogenic’ is often used for these, although it is not entirely applicable, since vertebrogenic disorders often include diseases with a pathomorphological definition, such as ankylosing spondylitis, osteoporosis, neoplasms, etc. Those which interest us, on the other hand, are mainly dysfunctions. They are not confined to the spinal column but also affect the limbs, soft tissues and, most of all, the musculature, which is controlled by the nervous system. In view of this it is more appropriate to speak of dysfunctions of the locomotor system, rather than vertebrogenic disturbances.

1.3.4. The place of reflex therapy

The question as to the place of reflex therapy is as difficult to answer as that of the importance of pharmacotherapy. Whereas pharmacotherapy has developed into a significant science, methods of reflex therapy for some time remained empirical, and the indications for their use are ill-defined.

The indication for a given treatment is not governed by the particular disease (diagnosis), but rather is based on the findings that are significant in terms of the pathogenesis. If, for example, headache is due to muscular tension, then muscle relaxation is most important. If this muscular tension is associated with joint restriction, then manipulation (mobilization) is indicated; if faulty posture is the cause, it is this that has to be corrected.

The advantages of this type of therapy over pharmacotherapy are that the methods used are entirely physiological and (usually) incur no side effects; further – because of their reflex nature – their effectiveness can generally be checked at once.

To sum up, neither the diagnosis nor individual clinical findings in themselves suffice as the basis for deciding the most appropriate therapy. An analysis of pathogenesis is the only means of identifying the disturbance that is the most important at a given moment.

After treatment the patient must be re-examined to assess the effect, and from this we can make further judgments about the appropriateness of the approach taken. If treatment has been effective, the follow-up examination will show a change in the patient’s condition (short term evidence). The task then begins again to decide which disturbance is now the most important.

Therapy is therefore never a monotonous routine; at the same time the success of treatment is always verifiable, and this aids the practitioner in applying a reasoned, scientific approach.