History and examination

• An acute illness, e.g. respiratory tract infection, meningitis, appendicitis

• A chronic problem, e.g. failure to thrive, chronic cough

• A newborn infant with a congenital malformation or abnormality, e.g. developmental dysplasia of the hip, Down syndrome

• Suspected delay in development, e.g. slow to walk, talk or acquire skills

• Behaviour problems, e.g. temper tantrums, hyperactivity, eating disorders.

The aims and objectives are to:

• establish the relevant facts of the history; this is always the most fruitful source of diagnostic information

• elicit all relevant clinical findings

• collate the findings from the history and examination

• formulate a working diagnosis or differential diagnosis on the basis of logical deduction

The above can be summarised by the acronym HELP:

Key points in paediatric history and examination are:

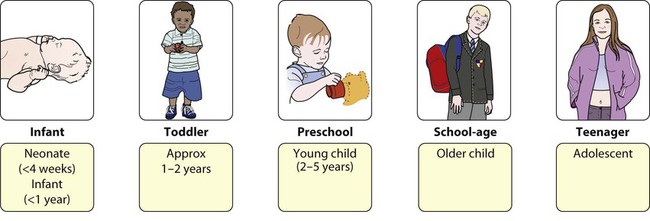

• the child’s age – a key feature in the history and examination (Fig. 2.1) as it determines:

– the nature and presentation of illnesses, developmental or behaviour problems

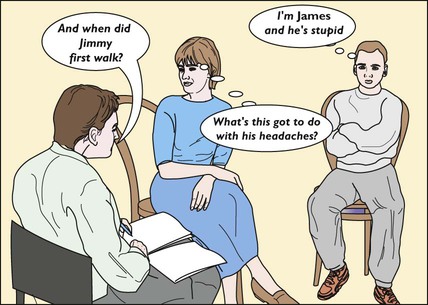

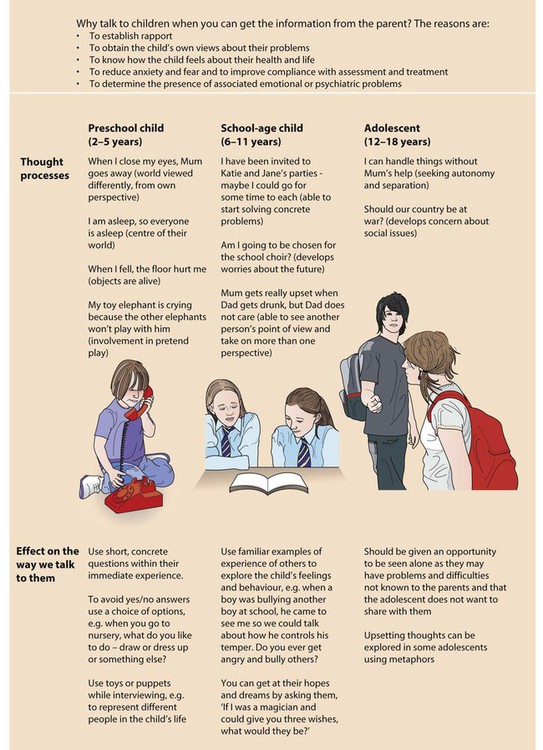

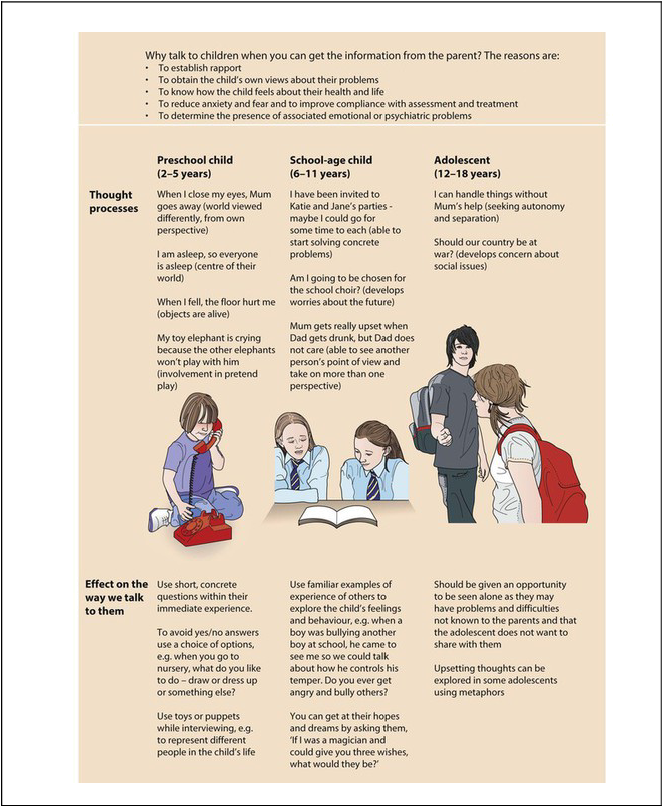

– the way in which the history-taking (Fig. 2.2) and examination are conducted

• the parents, who are astute observers of their children. Never ignore or dismiss what they say.

Taking a history

Introduction

• Make sure you have read any referral letter and scanned the notes before the start of the interview.

• Observe the child at play in the waiting area and observe their appearance, behaviour and gait as they come into the clinic room. The continued observation of the child during the whole interview may provide important clues to the diagnosis and management.

• When you welcome the child, parents and siblings, check that you know the child’s first name and gender. Ask how the child prefers to be addressed.

• Determine the relationship of the adults to the child.

• Establish eye contact and rapport with the family. Infants and some toddlers are most secure in parents’ arms or laps. Young children may need some time to get to know you.

• Ensure that the interview environment is as welcoming and unthreatening as possible. Avoid having desks or beds between you and the family, but keep a comfortable distance.

• Have toys available. Observe how the child separates, plays and interacts with any siblings present.

• Do not forget to address questions to the child, when appropriate.

• There will be occasions when the parents will not want the child present or when the child should be seen alone. This is usually to avoid embarrassing older children or teenagers or to impart sensitive information. This must be handled tactfully, often by negotiating to talk separately to each in turn.

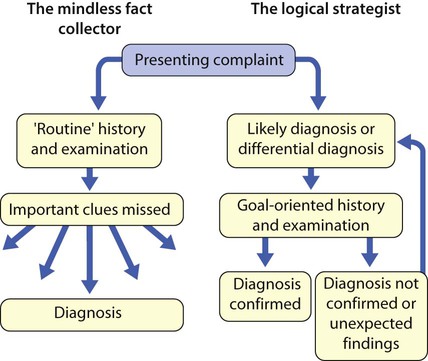

Presenting symptoms

The scope and detail of further history-taking are determined by the nature and severity of the presenting complaint and the child’s age. While the comprehensive assessment listed here is sometimes required, usually a selective approach is more appropriate (Fig. 2.3). This is not an excuse for a short, slipshod history, but instead allows one to focus on the areas where a thorough, detailed history is required.

Systems review

• General rashes, fever (if measured)

• Respiratory – cough, wheeze, breathing problems

• ENT – throat infections, snoring, noisy breathing (stridor)

• Cardiovascular – heart murmur, cyanosis, exercise tolerance

• Gastrointestinal – vomiting, diarrhoea/constipation, abdominal pain

• Genitourinary – dysuria, frequency, wetting, toilet-trained

• Neurological – seizures, headaches, abnormal movements

• Musculoskeletal – disturbance of gait, limb pain or swelling, other functional abnormalities.

Make sure that you and the parent or child mean the same thing when describing a problem.

Past medical history

• Maternal obstetric problems, delivery, prolonged rupture of membranes, group B streptococcus status, maternal pyrexia (pertinent if neonate)

• Perinatal problems, whether admitted to special care baby unit, jaundice, etc.

• Immunisations (ideally from the personal child health record)

• Past illnesses, hospital admissions and operations, accidents and injuries.

Social history

Development

• Parental worries about vision, hearing, development

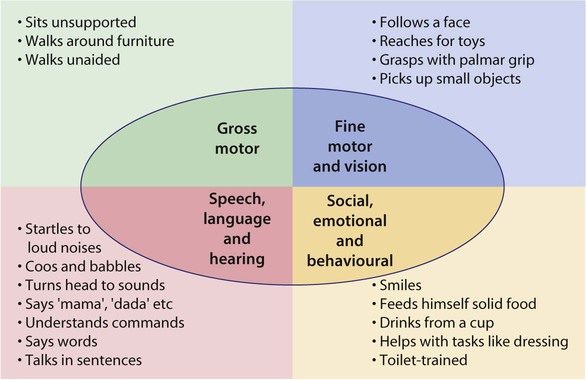

• Key developmental milestones (Fig. 2.4)

• Previous child health surveillance developmental checks

An approach to examining children

Obtaining the child’s cooperation

• Make friends with the child.

• Short mock examinations, e.g. auscultating a teddy or the mother’s hand, may allay a young child’s fears.

• When first examining a young child, start at a non-threatening area, such as a hand or knee.

• Explain what you are about to do and what you want the child to do, in language he can understand. As the examination is essential, not optional, it is best not to ask his permission, as it may well be refused!

• A smiling, talking doctor appears less threatening, but this should not be overdone as it can interfere with one’s relationship with the parents.

Adapting to the child’s age

• Babies in the first few months are best examined on an examination couch with a parent next to them.

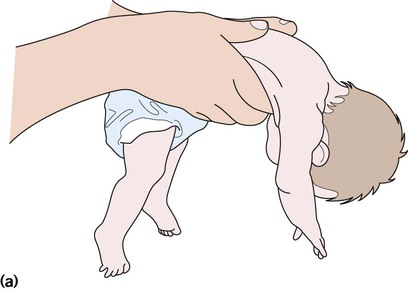

• A toddler is best initially examined on his mother’s lap or occasionally over a parent’s shoulder.

• Parents are reassuring for the child and helpful in facilitating the examination if guided as to what to do (Fig. 2.5).

• Preschool children may initially be examined while they are playing.

• Older children and teenagers are often concerned about privacy. Teenage girls should normally be examined in the presence of their mother, or a nurse or suitable chaperone. Be aware of cultural sensitivities in different ethnic groups.

Developmental skills

A good overview of developmental skills can be obtained by watching the child play. A few simple toys, such as some bricks, a car, doll, ball, pencil and paper, pegboard, miniature toys and a picture book, are all that is required, as they can be adapted for any age. If developmental assessment (see Ch. 3) is the focus of the examination, it is advisable to assess this before the physical examination, as cooperation may then be lost.

Examination

Initial observations

Respiratory system

Cyanosis

Central cyanosis is best observed on the tongue.

Auscultation (ears and stethoscope)

• Note quality and symmetry of breath sounds and any added sounds

• Harsh breath sounds from the upper airways are readily transmitted to the upper chest in infants

• Hoarse voice – abnormality of the vocal cords

• Stridor – harsh, low-pitched, mainly inspiratory sound from upper airways obstruction

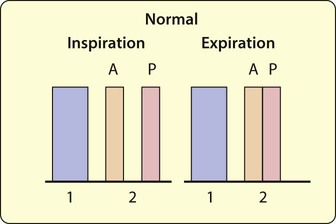

• Breath sounds – normal are vesicular; bronchial breathing is higher-pitched and the length of inspiration and expiration equal

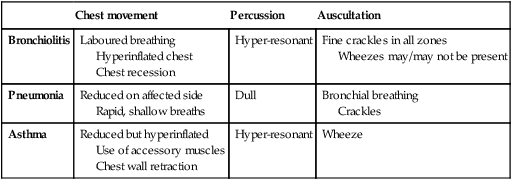

• Wheeze – high-pitched, expiratory sound from distal airway obstruction (Table 2.2)

• Crackles – discontinuous ‘moist’ sounds from the opening of bronchioles (Table 2.2).

Cardiovascular system

Cyanosis

Observe the tongue for central cyanosis.

Abdomen

Abdominal examination is performed in three major clinical settings:

Inspection

Generalised abdominal distension is most often explained by the five ‘F’s:

• Fluid (ascites – uncommon in children, most often from nephrotic syndrome)

Occasionally, it is caused by a grossly enlarged liver and/or spleen or muscle hypotonia.

Palpation

• Use warm hands, explain, relax the child and keep the parent close at hand. First ask if it hurts.

• Palpate in a systematic fashion – liver, spleen, kidneys, bladder, through four abdominal quadrants.

• Ask about tenderness. Watch the child’s face for grimacing as you palpate. A young child may become more cooperative if you palpate first with their hand or by putting your hand on top of theirs.

Tenderness

• Location – localised in appendicitis, hepatitis, pyelonephritis; generalised in mesenteric adenitis, peritonitis

• Guarding – often unimpressive on direct palpation in children. Pain on coughing, on moving about/walking/bumps during car journey suggests peritoneal irritation. Back bent on walking may be from psoas inflammation in appendicitis. By incorporating play into examination, more subtle guarding can be elicited. For example, a child will not be able to jump on the spot if they have localised guarding.

Hepatomegaly (Table 2.4, Fig. 2.8)

• Palpate from right iliac fossa

• Locate edge with tips or side of finger

• Measure (in cm) extension below costal margin in mid-clavicular line.

Percuss downwards from the right lung to exclude pseudohepatomegaly due to lung hyperinflation.

Liver tenderness is likely to be due to inflammation from hepatitis.

Abnormal masses

• Wilms’ tumour – renal mass, sometimes visible, does not cross midline

• Neuroblastoma – irregular firm mass, may cross midline; the child is usually very unwell

• Faecal masses – mobile, non-tender, indentable

• Intussusception – acutely unwell, mass may be palpable, most often in right upper quadrant.

Rectal examination

• This should not be performed routinely, and only for specific reasons

• Unpleasant and disliked by children

• Its usefulness in the ‘acute abdomen’ (e.g. appendicitis) is debatable in children, as they have a thin abdominal wall and so tenderness and masses can be identified on palpation of the abdomen. Some surgeons advocate it to identify a retrocaecal appendix, but interpretation is problematic as most children will complain of pain from the procedure.

• If intussusception is suspected, the mass may be palpable and stools looking like redcurrant jelly may be revealed on rectal examination.

Urinalysis

• Clean catch urine specimen preferred and the use of urine bags in the diagnosis of urine tract infection is not advisable

• Dipstick testing for proteinuria, haematuria, glycosuria, leukocyturia

• Examination of the microscopic appearance of urine is helpful for determining the origin of haematuria (crenated red cells, red cell casts).

Neurology/neurodevelopment

Brief neurological screen

• Use common sense to avoid unnecessary examination

• Take into consideration the parent’s account of developmental milestones.

In infants, assess primarily by observation:

• Observe posture and movements of the limbs.

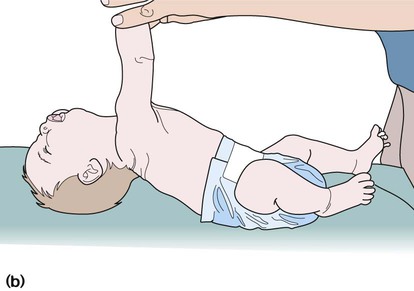

• When picking the infant up, note their tone. The limbs and body may feel normal, floppy or stiff. Head control may be poor, with abnormal head lag on pulling to sitting.

More detailed neurological examination

Patterns of movement

A broad-based gait may be due to an immature gait (normal in a toddler) or secondary to a cerebellar disorder. Proximal muscle weakness around the hip girdle can cause a waddling gait. Corticospinal tract lesions give a dynamic pattern of movement involving shoulder adduction, forearm pronation, elbow and wrist flexion with burying of the thumb, whereas internal hip rotation and flexion at the hip and knee and plantar flexion at the ankle give a characteristic circumduction pattern of lower limb movement. If subtle, these are more evident with asking the child to adopt an unusual pattern of walking, e.g. to walk on his heels or toes or with feet inverted. Extrapyramidal lesions give fluctuating tone, with difficulty in initiating or involuntary movements. Look for asymmetry (see Fig. 4.4).

Observe standing from lying down supine. Children up to 3 years of age will turn prone in order to stand because of poor pelvic muscle fixation; beyond this age, it suggests neuromuscular weakness (e.g. Duchenne muscular dystrophy) or low tone, which could be due to a central (brain) cause. The need to turn prone to rise or, later, as weakness progresses, to push off the ground with straightened arms and then climb up the legs is known as Gowers sign (see Fig. 27.6).

Coordination

• asking the child to build one brick upon another or using a peg-board, and do up and undo buttons, draw, copy patterns, write

• asking the child to hold his arms out straight and close his eyes, and then observing for drift or tremor (this is really looking for asymmetry, position sense, and neglect of one side with visual cues removed)

• finger–nose testing (use teddy’s nose to reach out and touch if necessary)

• rapid alternating movements of hands and fingers

Muscle tone

Tone, in limbs

• Best assessed by taking the weight of the whole limb and then bending and extending it around a single joint. Testing is easiest at the knee and ankle joints. Assess the resistance to passive movement as well as the range of movement.

• Increased tone (spasticity) in adductors and internal rotators of the hips, clonus at the ankles or increased tone on pronation of the forearms at rest is usually the result of pyramidal dysfunction. This can be differentiated from the lead-pipe rigidity seen in extrapyramidal conditions, which, if accompanied by a tremor may be termed ‘cog-wheel’ rigidity.

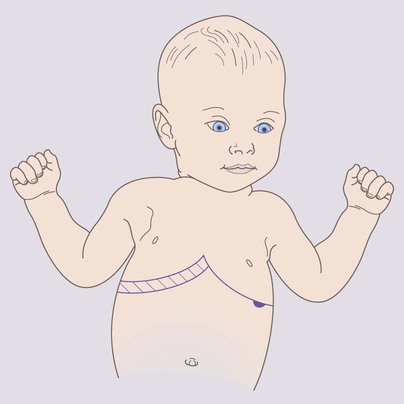

• The posture of the limbs may give a clue as to the underlying tone, e.g. scissoring of the legs, pronated forearms, fisting, extended legs suggests increased tone (see Figs 4.3 and 4.4). Sitting in a frog-like posture of the legs suggests hypotonia (see Fig. 8.2a), while abnormal posturing and extension suggests fluctuating tone (dystonia).

Cranial nerves

| I | Need not be tested in routine practice. Can be done by recognising the smell of a hidden mint sweet. |

| II | Visual acuity – determined according to age. Direct and consensual pupillary response tested to light and accommodation. Visual fields can be tested if the child is old enough to cooperate. |

| III, IV, VI | Full eye movement through horizontal and vertical planes. Is there a squint? Nystagmus – avoid extreme lateral gaze, as it can induce nystagmus in normal children. |

| V | Clench teeth and waggle jaw from side to side against resistance. |

| VII | Close eyes tight, smile and show teeth. |

| VIII | Hearing – ask parents, although unilateral deafness could be missed this way. If in doubt, needs formal assessment in a suitable environment. |

| IX | Levator palati – saying ‘aagh’. Look for deviation of uvula. |

| X | Recurrent laryngeal nerve – listen for hoarseness or stridor. |

| XI | Trapezius and sternomastoid power – shrug shoulders and turn head against resistance. |

| XII | Put out tongue and look for any atrophy or deviation. |

Bones and joints

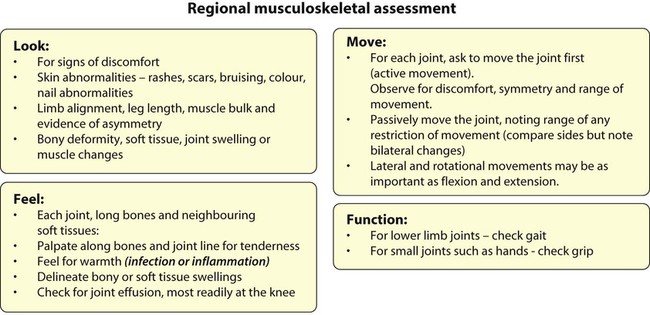

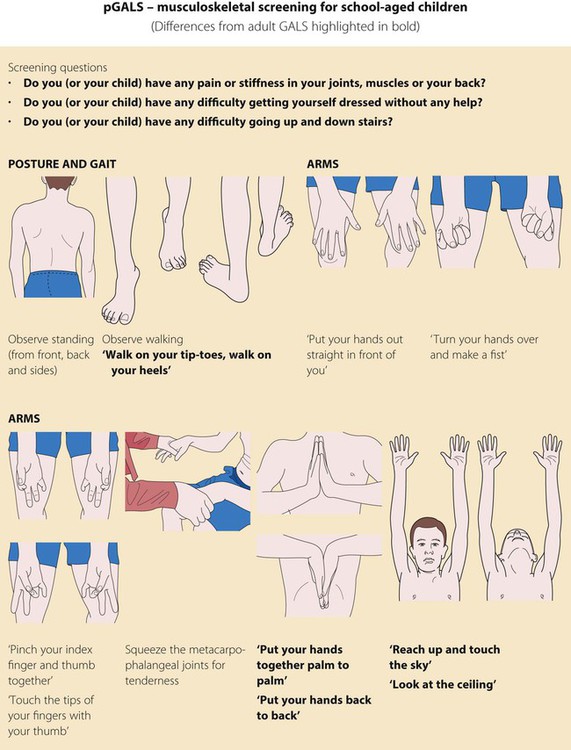

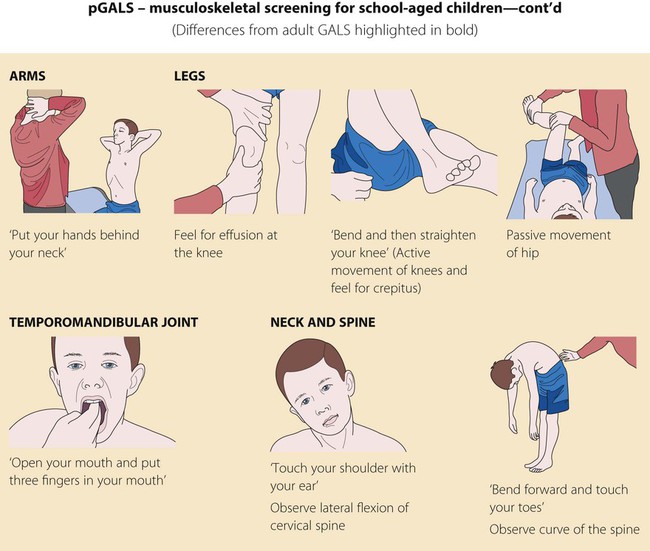

A rapid screen to identify disorders of the musculoskeletal is pGALS (paediatric Gait, Arms, Legs, Spine; Fig. 2.10). If an abnormality is found, a more detailed regional examination of the affected joint as well as the joint above and below should be performed (Fig. 2.11).

Neck

Thyroid

• Inspect – swelling uncommon in childhood; occasionally at puberty

• Palpate from behind and front for swelling, nodule, thrill

Lymph nodes

• Small, discrete, pea-sized, mobile nodes in the neck, groin and axilla – common in normal children, especially if thin

• Small, multiple nodes in the neck – common after upper respiratory tract infections (viral/bacterial)

• Multiple lymph nodes of variable size in children with extensive atopic eczema – frequent finding, no action required

• Large, hot, tender, sometimes fluctuant node, usually in neck – infected/abscess

Blood pressure

Indications

Must be closely monitored if critically ill, if there is renal or cardiac disease or diabetes mellitus, or if receiving drug therapy which may cause hypertension, e.g. corticosteroids (Box 2.1). Not measured often enough in children.

Technique

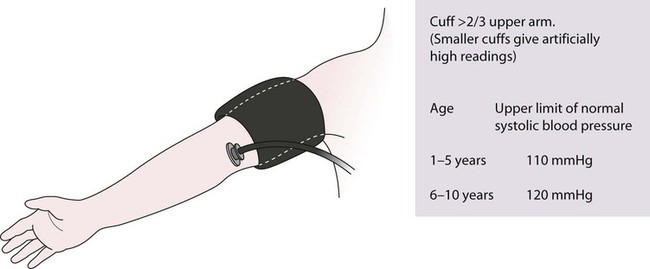

When measured with a sphygmomanometer:

• Show the child that there is a balloon in the cuff and demonstrate how it is blown up.

• Use largest cuff which fits comfortably, covering at least two-thirds of the upper arm.

• The child must be relaxed and not crying.

• Systolic pressure is the easiest to determine in young children and clinically the most useful.

• Diastolic pressure is when the sounds disappear. May not be possible to discern in young children. Systolic pressure used in clinical practice.

Measurement

Must be interpreted according to a centile chart (see Fig. A.3, in the Appendix). Blood pressure is increased by tall stature and obesity. Charts relating blood pressure to height are available and preferable; however, for convenience, charts relating blood pressure to age are often used. An abnormally high reading must be repeated, with the child relaxed, on at least three separate occasions.

Eyes

Examination

Inspect eyes, pupils, iris and sclerae. Are eye movements full and symmetrical? Is nystagmus detectable? If so, may have ocular or cerebellar cause, or testing may be too lateral to the child. Are the pupils round (absence of posterior synechiae), equal, central and reactive to light? Is there a squint? (see Ch. 4).

Epicanthic folds are common in Asian ethnic groups.

Ophthalmoscopy

• In infants, the red reflex is seen from a distance of 20–30 cm. Absence of red reflex occurs in corneal clouding, cataract, retinoblastoma.

• Fundoscopy – difficult. Requires experience and cooperation. In infants, mydriatics are needed and an ophthalmological opinion may be required. Retinopathy of prematurity and retinopathy of congenital infections and choroido-retinal degeneration show characteristic findings. Retinal haemorrhages may be seen in head trauma or in ‘shaken baby syndrome’ (non-accidental injury).

• In older children with headaches, diabetes mellitus or hypertension, optic fundi should be examined. Mydriatics are not usually needed.

Summary and management plan

At the end of the history and examination:

• Summarise the key problems (in physical, emotional, social and family terms, if relevant).

• List the diagnoses or differential diagnoses. Draw up a management plan to address the problems, both short and long term. This could be reassurance, a period of observation, performing investigations or therapeutic intervention.

• Provide explanation to the parents and to the child, if old enough. Consider providing further information, either written or on the internet.

• If relevant, discuss what to tell other members of the family.

• Consider which other professionals should be informed.

• Write a brief summary in the child’s personal child health record.