3

History and examination

Introduction

In general, history and examination cannot be divided neatly into different specialties, and questions relating to obstetrics and gynaecology should form part of the assessment of any woman presenting to any specialty. There may be embarrassment and recrimination, for example, when a suspected appendicitis turns out to be a pelvic infection secondary to an unsuspected intrauterine contraceptive device. Similarly, not all problems presenting to obstetricians and gynaecologists are obstetrical or gynaecological in nature. It is therefore important to take a full history and perform an appropriate examination in all cases. The key points of gynaecological and obstetrical history and examination are emphasized below.

Gynaecological history

A gynaecological history should follow the usual model for history-taking, with questions about the presenting complaint, its history and associated problems. It should include a past medical history and information about prescription and non-prescription drugs used, and any known allergies. After questions about social circumstances and activities, and family history, the history is completed with a general systemic enquiry. However, during a gynaecological history, there are specific key areas to be expanded upon. These include menstrual, fertility, pelvic pain, urogynaecological and obstetrical histories.

Menstrual history

The pattern of bleeding

The simple phrase ‘tell me about your periods’ often elicits all the information required. The bleeding pattern of the menstrual cycle is expressed as a fraction, such that a cycle of 4/28 means the woman bleeds for 4 days every 28 days. A cycle of 4–10/21–42 means the woman bleeds for between 4 and 10 days every 21–42 days. Asking the shortest time between the start of successive periods, the longest time between periods, and the average time between periods helps determine the cycle characteristics.

Bleeding too little

Amenorrhoea is the absence of periods. Primary amenorrhoea is when someone has not started menstruating by the age of 16. Secondary amenorrhoea means that periods have been absent for longer than 6 months. Oligomenorrhoea means the periods are infrequent, with a cycle of 42 days or more.

The climacteric is the perimenopausal time when periods become less regular and are accompanied by increasing menopausal symptoms. The menopause is the time after the last ever period, and can only therefore be assessed retrospectively.

Irregular periods, oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea, suggest anovulation or irregular ovulation. Specific questions about weight, weight change, acne, greasy skin, hirsutism, flushes or galactorrhoea may help identify the nature of the ovarian dysfunction.

Bleeding too much

It is very difficult to find out how heavy someone’s periods are. If menstrual blood loss is accurately measured, an average of 35 ml of blood is lost each month. Heavy menstrual bleeding (previously known as menorrhagia) is defined as loss of more than 80 ml during regular menstruation. Some women will complain of very heavy periods with a normal blood loss, while others will not complain in the presence of heavy menstrual bleeding. Asking how often pads or tampons have to be changed and using pictorial charts can provide more objective information. Whether menstrual loss is excessive, however, is a largely subjective assessment.

Specific symptoms can indicate abnormally heavy menstruation. Although small pieces of tissue are normal, blood clots are not. ‘Flooding’ is when menstrual blood soaks through all protection. It is both abnormal and distressing. Symptoms of anaemia may also be present. A history of the menstrual cycle since menarche (the first period) can reveal changes in the bleeding pattern. However, an emphasis on the effect on lifestyle and treatments tried previously is particularly important.

Bleeding at the wrong time

It is important to ask specifically about bleeding, brown or bloody discharge between periods (intermenstrual bleeding, IMB), or after intercourse (post-coital bleeding, PCB). These symptoms can point to abnormalities of the cervix or uterine cavity. Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is defined as bleeding more than 1 year after the last period. Undiagnosed abnormal bleeding requires further investigation.

Fertility history

Last menstrual period (LMP)

This question is vital and should be followed with whether that period came at the expected time and was of normal character. As well as alerting to the possibility of pregnancy, the information is important because some investigations need to be performed at specific times of the menstrual cycle.

Contraception

It is useful to establish whether the woman is sexually active, perhaps with something like, ‘Are you currently in a physical sexual relationship?’ and then, ‘Are you using any contraception at present?’ A further discussion about fertility issues, unprotected intercourse and risk factors for certain diseases may be appropriate. A contraceptive history should include any problems with chosen contraceptives and why they were stopped. Questions may be followed-up with ‘Are you hoping for a pregnancy?’ if the situation is not clear.

If there are any infertility issues, their duration and the results of any investigation or treatment may be of relevance. If the woman is postmenopausal, enquiry should be made about past or current use of hormone replacement therapy and whether she has any symptoms attributable to the menopause.

Cervical smears

Cervical screening programmes vary in different countries but generally, women between the ages of 20–25 and 60–64 are invited to participate every 3–5 years. The date of the woman’s last smear should be noted, and when it was recommended that she have her next smear. Any previous abnormalities or vaccination should also be noted, and whether she has had any colposcopic investigation or treatment. If she is over 50, it may be relevant to discuss breast screening.

Pelvic pain history

Painful periods

Dysmenorrhoea is a common problem and its effects on lifestyle are important. The cramping pain of primary dysmenorrhoea is at its most intense just before and during the early stages of a period. Young women are particularly affected and the pain has usually been present from the time of the first period. It is not usually associated with structural abnormalities and may improve with age or after a pregnancy. Secondary dysmenorrhoea is when menstruation has not tended to be painful in the past, and is more likely to indicate pelvic pathology. In particular, progressive dysmenorrhoea, where the intensity of the pain increases throughout menstruation, may suggest endometriosis.

Pelvic pain

The relationship of pelvic pain to the menstrual cycle is important. Pain immediately prior to or during periods is more likely to be of gynaecological origin. ‘Mittelschmerz’ is a cramping pelvic pain that can be midline or unilateral. It occurs 2 weeks before a period and is caused by ovulation. Intermittent discomfort may suggest some scarring or ovarian pathology but it is more commonly non-gynaecological. It is vital to take a urinary and lower gastrointestinal history as urinary tract infection or irritable bowel syndrome may present with pelvic pain. Any pain is likely to be worse if the person is anxious, stressed or depressed. Chronic pelvic pain is particularly affected by psychosomatic factors, and recognizing this during history-taking is important.

Pain on intercourse

There are two main types of dyspareunia: superficial and deep. They can be differentiated by asking, ‘Is it painful just as he begins to enter or when he is deep inside?’ Deep dyspareunia is associated with pelvic pathology, such as scarring, adhesions, endometriosis or masses that restrict uterine mobility. Superficial dyspareunia can arise from local abnormalities at the introitus or from inadequate lubrication. It can also be due to a voluntary or involuntary contraction of the muscles of the pelvic floor referred to as ‘vaginismus’ (see Chapter 25).

Vaginal discharge

Discharge can be normal or be associated with cervical ectopy and, particularly if offensive or irritant, can indicate infection. It can also suggest neoplasia of the cervix or endometrium. Enquire about the duration, amount, colour, smell and relationship to cycle.

Urogynaecological history

Urinary incontinence

A good initial question to ask is, ‘Do you ever leak urine when you don’t intend to?’ If so, find out what provokes it, how it affects her lifestyle and what steps she takes to avoid it. ‘Do you ever not make it to the toilet in time?’ can help identify urge incontinence, as can a history of frequency and small volumes passed after desperation. Incontinence after exercise, coughing, laughing or straining can suggest stress incontinence. It can be difficult to differentiate stress incontinence and urge incontinence, however, as there is often a mixed picture.

Other urinary symptoms

Enquiry should be made about frequency and nocturia. If present, small volumes and an inability to interrupt the flow may suggest detrusor instability. If large volumes are passed, ask about thirst and fluid intake. A history of dysuria or haematuria may suggest bladder infection or pathology. ‘Strangury’ is the constant desire to pass urine and suggests urinary tract inflammation.

Prolapse

Prolapse may be associated with vaginal discomfort, a dragging sensation, the feeling of something ‘coming down’ and possibly backache. Although the uterus, anterior vaginal wall and posterior vaginal wall can prolapse, it is difficult to separate these by history. Bladder and bowel function should be explored, including a question about the need to digitally manipulate the vagina in order to be able to void.

Gynaecological examination

Signs of gynaecological disease are not limited to the pelvis. A full examination may reveal anaemia, pleural effusions, visual field defects or lymphadenopathy in gynaecological conditions. However, passing a speculum, taking a cervical smear and performing a bimanual pelvic examination are the key skills to acquire. A great deal of sensitivity is required in their use.

Passing a speculum

Preparation

The patient should empty her bladder and remove sanitary protection. The examination room should be quiet and have a private area for the patient to undress. It should contain an examination couch with a modesty sheet and good adjustable lighting. A female chaperone should always be present. The examination requires full explanation and verbal consent.

Stand on the right of the patient with gloves, speculum and lubricating gel immediately to hand. The patient should lie back, bend her knees, put her heels together and let her knees fall apart. The light should be adjusted to give a good view of the vulva and perineum and the modesty sheet should cover the patient’s abdomen and thighs.

Inspection

Inspect the hair distribution and vulval skin. Hair extending towards the umbilicus and onto the inner thighs can be associated with disorders of androgen excess, as can clitoromegaly. The vulva can be a site of chronic skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis, specific conditions such as lichen sclerosis and warts, cysts of the Bartholin’s glands (see History box), and cancers. Ulceration may imply herpes, syphilis, trauma or malignancy.

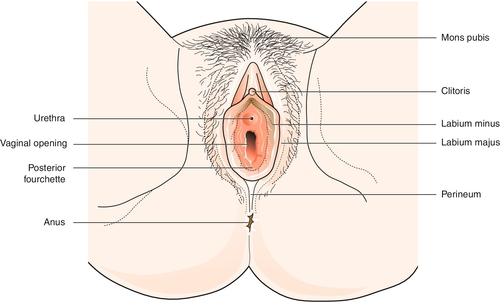

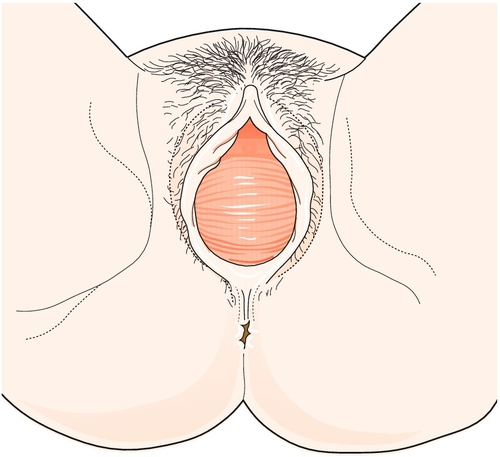

Look at the perineum (Fig. 3.1) and gently part the labia to inspect the introitus. Perineal scars are usually secondary to tears or episiotomy during childbirth. A red papule around the urethral opening is usually a prolapsed area of urethral mucosa. A white, plaque-like discharge may suggest thrush, and pale skin with punctate red areas implies atrophic vaginitis. Asking the woman to cough may reveal demonstrable stress incontinence or the bulge of a prolapse.

Speculum examination

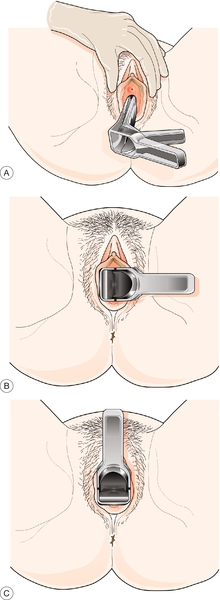

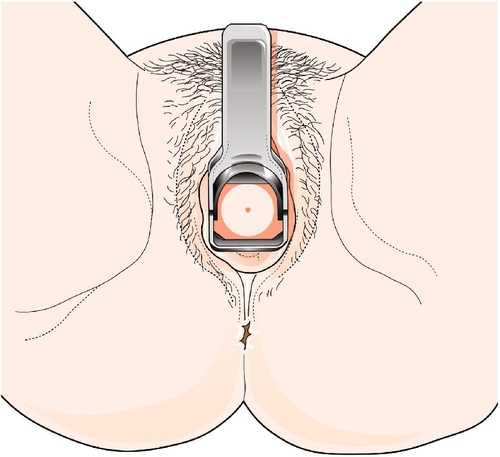

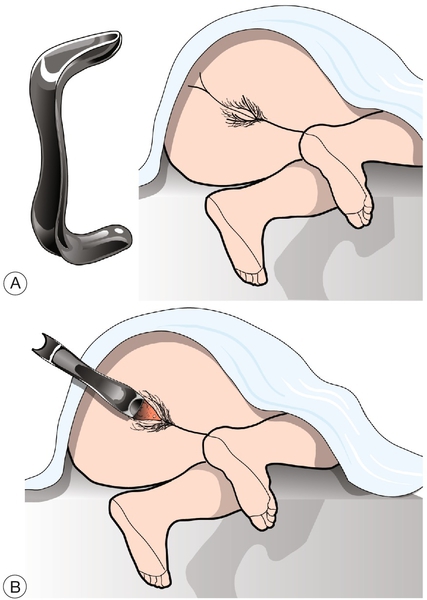

Disposable speculums tend to be all one size, but smaller and larger speculums are available if required. Ensure the speculum is warmed, working normally and lubricated with gel. Hold the speculum so that its blades are oriented in the same direction as the vaginal opening. Part the labia and slowly insert the speculum, rotating it gently until the blades are horizontal (Fig. 3.2).

If the patient is in the lithotomy position at the edge of the couch, the speculum can be turned downwards to avoid pressure on the clitoris. If the patient is lying on the couch itself, it is usually easier to rotate the speculum upwards. It should be inserted fully in a slightly posterior direction, before firmly, but gently, opening to visualize the cervix (Fig. 3.3). The speculum can be closed a little when the cervix pops into view.

If the cervix is not visible, it is often because the speculum has not been inserted far enough before opening. If this is not the case, the cervix is either above or below the blades. As most uteri are anteverted, it is usually below the blades, and the speculum should be angled more posteriorly before reopening. Otherwise, gently insert a finger to determine its position.

Inspect the vagina for atrophic vaginitis and discharge. A creamy or mucousy discharge is normal. A yellow-greenish frothy discharge is seen with Trichomonas vaginalis and a grey-green fishy discharge suggests bacterial vaginosis. There may be a purulent cervical discharge with gonorrhoea, and an increased mucousy discharge may occur with chlamydial cervicitis. Swabs, if required, should be taken from the vaginal fornices (high vaginal) or the cervical canal (endocervical).

The cervical os is small and round in the nulliparous and bigger and more slit-like in parous women. Threads from an IUCD may be present. Translucent lumps or cysts around the os are Nabothian follicles (see History box), but warts and tumours can sometimes be seen. An ectopy is red, as the epithelium of the cervical canal extends onto the surface of the paler outer cervical epithelium. It varies across the cycle and should be looked on as normal, although it may be associated with contact bleeding or increased discharge.

The speculum should be opened further and withdrawn beyond the cervix before rotation back again, closure and removal.

Taking a cervical smear

Smears should ideally be performed in the mid- to late follicular phase and not during menstruation. Confirm the woman’s details and ensure you have ascertained all the information required for the request form. Run the speculum under warm water to provide appropriate lubrication and visualize the cervix.

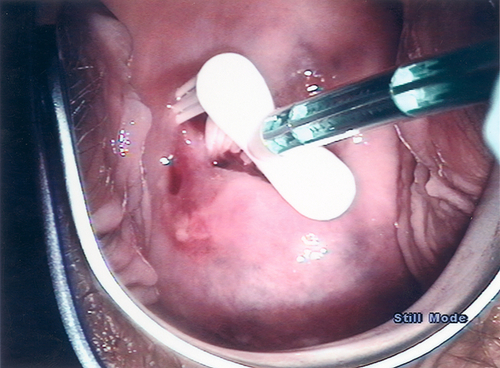

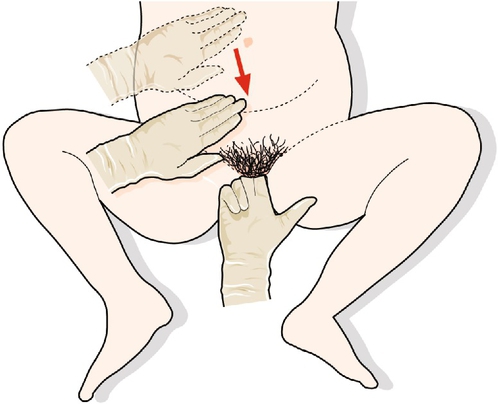

The most commonly used technique involves using liquid-based cytology and a broom-type sampling device. Insert the central bristles of the broom-like device into the endocervical canal, deep enough to allow the shorter bristles to fully contact the ectocervix. Push gently and rotate the broom in a clockwise direction five times (Fig. 3.4).

Immediately put the broom into the container of preserving solution and rinse as quickly as possible, by rotating 10 times, while pushing against the side of the container. Discard the broom, tighten the lid, and label the container with the patient’s details. Complete and check the cytology request form, ensuring that all the information required is provided, and marry this, or the computer-generated barcode if the form is completed electronically, to the container for transport to the laboratory. Inform the woman how long the result will take and how it will be delivered.

A bivalve speculum holds open the vaginal walls and obscures any cystocele or rectocele. A univalve speculum can demonstrate these. The patient lies in the left-lateral position with her knees drawn up. The lubricated blade of the speculum is used to hold back the anterior vaginal wall. Coughing will show a bulge of the posterior wall if a rectocele is present. When the posterior wall is held back, coughing will demonstrate the bulge of a cystocele and/or uterine descent (Figs 3.5 and 3.6).

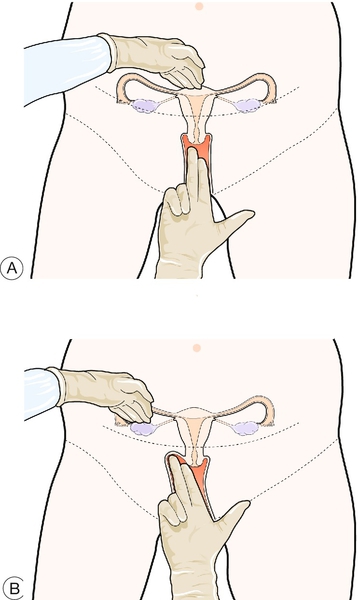

Pelvic examination

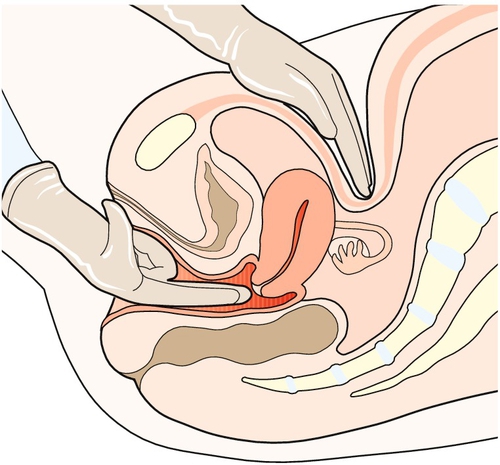

Apply lubricating gel to the gloved fingers of the right hand. Part the labia with the index and middle fingers of the left hand. Gently slip the right index finger into the vagina. If comfortable, slip the middle finger in below the index finger, making room posteriorly to avoid the sensitive urethra. The cervix feels like the tip of a nose and protrudes into the top of the vagina (Fig. 3.7).

Feel the cervix and record irregularities or discomfort. ‘Cervical excitation’ is when touching the cervix causes intense pain and it implies active pelvic inflammation. The dimple of the os can be felt and the firmness of the uterine body lies above or below the cervix. A vaginal cyst may be an embryological duct remnant, and vaginal nodules may represent endometriosis.

Assess the position of the uterus. It is usually anteverted with the cervix posterior and the uterine body anterior. If the uterus is retroverted, the cervix is anterior and the uterine body lies posteriorly. The fingers should be manipulated behind the cervix to lift the uterus. With the left hand above the umbilicus, feel through the abdomen for the moving uterus (Fig. 3.8). If the uterus cannot be palpated, the hand should be moved gradually down until the uterus is between the fingers (Fig. 3.9A).

Assess the mobility, regularity and size of the uterus. The adhesions of endometriosis, infection, surgery or malignancy fix the uterus and make bimanual examination more uncomfortable. Asymmetry of the uterus may imply fibroids. Uterine size is often related to stage of pregnancy. A normally sized uterus feels like a plum. At 6 weeks, a pregnant uterus feels like a tangerine, at 8 weeks an apple, at 10 weeks an orange and at 12 weeks a grapefruit. At 14 weeks, the uterus can be felt on abdominal palpation alone.

Feel for adnexal masses in the vaginal fornices lateral to the cervix on each side. Push up the tissues in the adnexa and, starting with a hand above the umbilicus, bring it down to the appropriate iliac fossa, trying to feel a mass bimanually (Fig. 3.9B). In thin women, the ovaries can just be felt, but a definite adnexal mass is abnormal and should be investigated further. As large adnexal masses tend to move to the midline, it can be difficult to differentiate a large ovarian cyst from a large uterus.

Obstetrical history

An obstetrical history follows the usual model for history-taking. However, as with gynaecological histories, there are several unique things to be covered. A history from a pregnant woman starts with calculating the gestation and putting this pregnancy in the context of previous pregnancies. The presenting complaint is next and this encompasses a record of what is happening now, risk factors and symptom progression. It is followed by a complete history of this pregnancy and previous pregnancies. After this, medical, gynaecological, drug, social and family histories are expanded. However, these are often straightforward, as pregnant women are usually young and healthy.

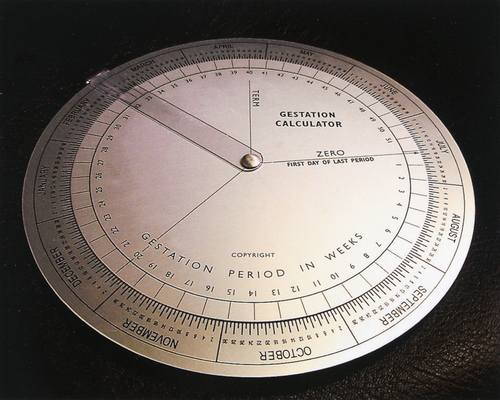

Establishment of the estimated day of delivery (EDD)

Term is between 37 and 42 weeks’ gestation, but the actual EDD is 40 weeks after day 1 of the last menstrual period (LMP). This can cause confusion, as gestation is calculated from the LMP, not conception. When someone is 12 weeks’ pregnant, she conceived 10 weeks ago. Phone-based apps or gestational wheel calculators allow the easy calculation of EDD and current gestation from the LMP (Fig. 3.10). In their absence, Naegele’s rule (see History box) can be used. To calculate the EDD, subtract 3 months from the LMP and add 10 days.

These methods assume a regular 4-week cycle. If this is not the case, the EDD may require adjustment. With a regular 5-week cycle, the true EDD will be 1 week later than calculated. An ultrasound scan (USS) is used to confirm the final EDD. However, scans have an associated error that increases with gestation, and in the early second trimester, this is approximately plus or minus 1 week. In general, the EDD from the LMP is used, unless the USS date differs by more than a week.

Obstetrical summary

Parity is a summary of a woman’s obstetrical history and two numbers are used to document this. Added together, the numbers give the number of previous pregnancies. Someone who is para 0 + 0 has not been pregnant before. The first number is the total number of live births, plus the number of stillbirths after 24 weeks’ gestation. The second number is the number of pregnancies before 24 weeks, in which the baby was not born alive.

A woman who is para 3 + 3 has been pregnant six times. The first ‘3’ might represent a normal term delivery, a live birth at 23 weeks after which the baby died and a stillbirth at 25 weeks’ gestation. The other three pregnancies may have been a spontaneous miscarriage at 23 weeks, an early ectopic pregnancy and a first trimester termination. The numbers relate to pregnancies rather than babies, so that the mother of twins would be para 1 + 0. A woman who is primiparous is ‘pregnant and para 0’. A parous woman is ‘pregnant and para 1’ (or more).

What is happening now?

The next stage is the presenting complaint and its history. Assuming there is a specific problem, the history should include when it was first noticed, its progress, management and associated symptoms. It may also be useful to ask about important risk factors, for example a past history of placental abruption, chronic hypertension, smoking or pre-eclampsia.

Remember that there are two patients. The fetus should be assessed by asking about movements, and any recent tests of fetal well-being. Fetal movements are first felt around 20 weeks, a time referred to as the ‘quickening’ but can be as early as 16 weeks. Normally, there are several movements each hour but they are more frequently noticed when concentrated on. Kick charts usually involve noting the time when 10 movements have occurred.

History of this pregnancy

This pregnancy should now be covered in detail. The first thing to ask about is pre-conceptual folic acid, followed by the diagnosis of pregnancy and problems such as bleeding and vomiting or pain in the first trimester. The next thing to ask about is the booking appointment, results of investigations, including dating and anomaly USS and additional prenatal screening tests. Then cover subsequent antenatal care, including clinics, parentcraft and any day unit assessment. The reason for and outcome of any additional USS should be reported. Any concerns, problems identified or emergency attendance at hospital should be documented, along with plans for the rest of the pregnancy and delivery.

Past obstetric history

Each of the woman’s previous pregnancies should be discussed chronologically. Information required includes the date, the gestation and outcome. If the pregnancy ended in the first or second trimester, the diagnosis and management, including any operative procedures, should be recorded. For other pregnancies, information about the method of delivery, the reason for an operative delivery, the sex, weight, health and method of feeding of the baby should be obtained. In particular, any pregnancy and postnatal complication should be highlighted.

Medical history

The medical history should include previous operations, hospitalizations and medical problems. Continuing medical problems are of great importance because they may have an effect on the pregnancy and make complications more likely or complex. In addition, pregnancy may have an effect on medical problems, resulting in their deterioration, improvement or an alteration in management.

Gynaecological history

All or some of the gynaecological topics may be important in the history. Infertility treatment, particularly the use of assisted reproductive technologies, such as egg donation, pre-gestational diagnosis or screening (ICSI), may suggest the need to modify counselling and tests. The date of the last cervical smear is relevant.

Drug history

It is important to record drugs taken, both over-the-counter and prescribed, and the reasons for their use. The need to continue the drug, or change its dose, as well as any possible teratogenic effects, should be considered.

Family history

In a pregnant woman, it is a family history of fetal abnormalities, genetic conditions or consanguinity that is particularly important. In addition, some obstetrical conditions such as twins, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes and obstetric cholestasis may have a familial element.

Social history

It is important to assess the facilities for the forthcoming baby and determine whether further support is required. The woman’s occupation and her plans for working during the pregnancy should be noted. It is also important to ask about smoking, drinking and other drugs of misuse.

Systemic enquiry

Often, the systemic enquiry will be covered in the history of the presenting complaint. Remember, however, that many symptoms are more common in pregnancy, including urinary frequency, shortness of breath, tiredness, headache, nausea and breast tenderness.

Low-risk versus high-risk pregnancy

The key to good antenatal care is to recognize which women are more likely to develop problems in pregnancy before they happen. Clearly, all women can develop problems, but women at extremes of age and weight, those with pre-existing medical conditions like diabetes, hypertension and epilepsy, those with significant past or family histories of obstetric problems, and those who smoke heavily, misuse drugs or have poor social circumstances are all more likely to develop problems. In these ‘high-risk’ pregnancies, antenatal care should be tailored to meet the increased needs of the woman and fetus.

Obstetrical examination

In an obstetrical examination, the areas to focus on should be guided by the clinical history. It is only by becoming familiar with examination findings in normal pregnancy that deviations from normal can be fully appreciated. In the hyperdynamic circulation of pregnancy, for example, cardiac murmurs are common. The vast majority of these are flow murmurs, but previously unrecognized pathological murmurs occasionally become apparent. Likewise, in normal pregnancy, skin changes and increasing oedema are common.

A systematic approach is preferable. Starting with the hands and working up to the head and down to the abdomen and legs, will avoid missing important signs. Examination of the skin, sclera, conjunctiva, retina, thyroid, liver and tendon reflexes may reveal important abnormalities that may otherwise be missed. There are three elements of obstetrical examination, however, that are particularly important: blood pressure assessment, abdominal palpation and vaginal examination.

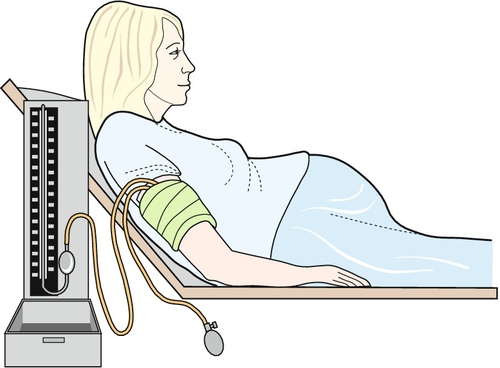

Blood pressure assessment

The pregnant woman should lie in a semirecumbent position at an approximately 30° angle and time should be taken to ensure that she is relaxed. The room should be quiet, and any tight clothing on her arm removed. The blood pressure should be taken from her right arm, supported at the level of the heart (Fig. 3.11).

An appropriately sized cuff should be used, as too small a cuff will overestimate the blood pressure. The best cuffs have an indication of acceptable arm circumference on them. Ideally, the cuff bladder should cover 80% of the arm circumference and the width of the bladder should be 40% of the arm circumference. Problems occur if the bladder length is < 67% (this usually means the arm circumference is > 34 cm). In such cases, a large or thigh cuff should be used.

Place the centre of the cuff bladder directly over the brachial artery on the inner side of the right upper arm, at the same level as the sternum at the fourth intercostal space. Apply the cuff all round, evenly and firmly but not tightly, with the connecting tubes pointing upwards and the antecubital fossa free. Palpate the brachial artery in the antecubital fossa and place the bell end of the stethoscope over it without undue pressure.

Rapidly pump the pressure in the sphygmomanometer cuff to 20–30 mmHg above the point where brachial artery pulsation ceases. Let the air out at 2–3 mmHg per second. The systolic blood pressure (SBP) is the point where the first clear tapping sound is heard. Read the top of the meniscus or needle to the nearest 2 mmHg. The diastolic blood pressure (DBP) is the point where the Korotkoff (romanized, see History box) sounds first become muffled (phase IV), rather than where they disappear (Korotkoff V). Ideally, the record should detail which phase was used, and if there is uncertainty, the measurement can be repeated.

Abdominal palpation

Ensure the patient has privacy, is comfortable and relaxed. Although pregnant women should avoid lying flat on their back for any period of time as this can compress major vessels, the woman should be examined in the recumbent position.

Initially, the abdomen is inspected. During inspection, look for the distended abdomen of pregnancy and note asymmetry, fetal movements and tense stretching. The skin may reveal old or fresh striae gravidarum, a midline pigmented linea nigra and any scars from previous surgery. The most common scars to note, are the Pfannenstiel (see History box) scars of previous pelvic surgery, the small subumbilical and suprapubic scars of laparoscopy and the gridiron incision of a previous appendicectomy.

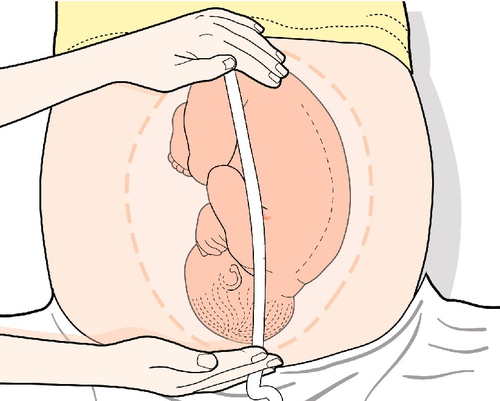

The next stage is palpation. This begins with the symphysiofundal height (SFH) (Fig. 3.12). The uterus is palpated with the palm of the left hand, moving it upwards and pressing with the lateral border. There is a ‘give’ at the fundus. Hold the end of a tape measure, measuring-side (i.e. centimetre-side) down, at the fundus and mark the tape at the upper border of the pubic symphysis.

At 20 weeks’ gestation, the uterus comes up to around the umbilicus and the SFH is ~ 20 cm. Each week, the uterus grows 1 cm, so that at 28 weeks, it is ~ 28 ± 2 cm and at 32 weeks, it is ~ 32 ± 2 cm. Metric measurement is therefore a reasonable guide to the size for gestation, and is useful in identifying those that are large- or small-for-dates.

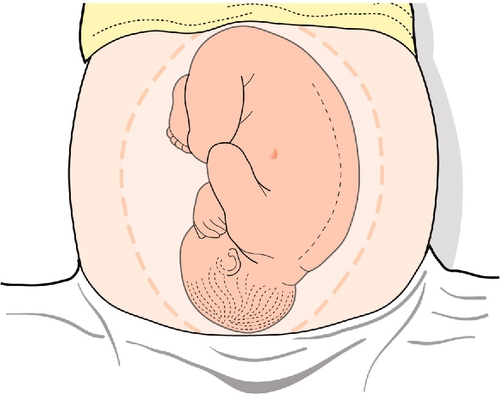

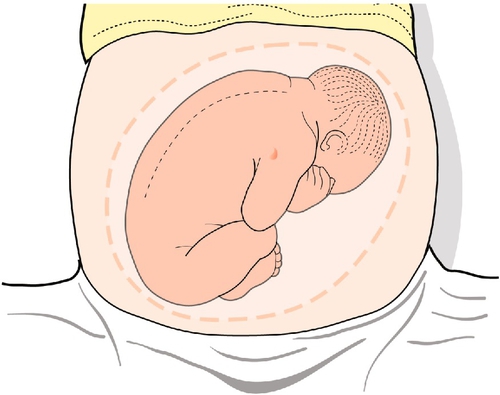

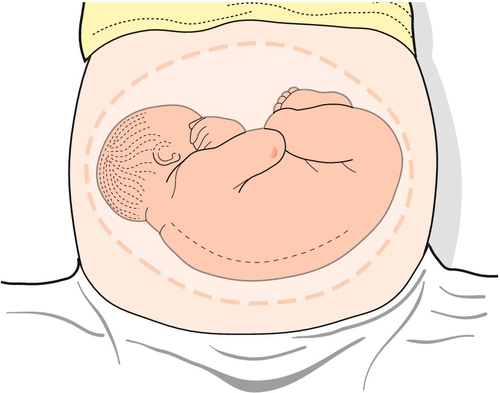

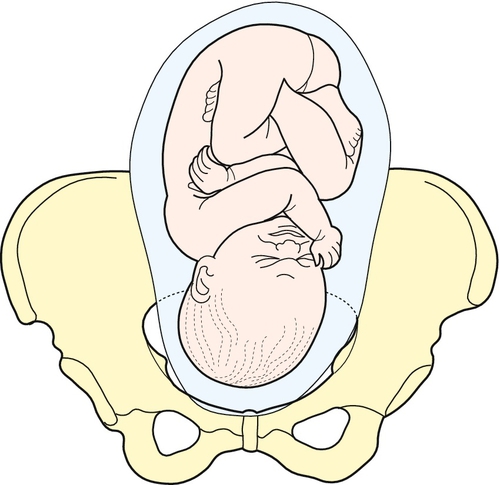

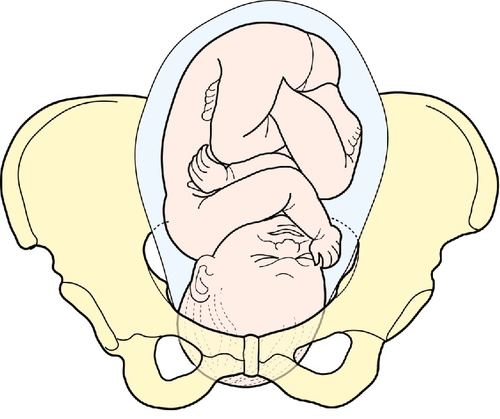

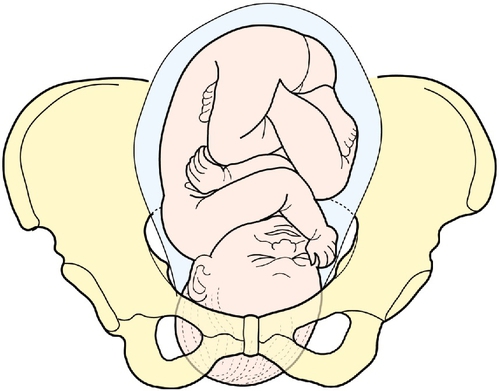

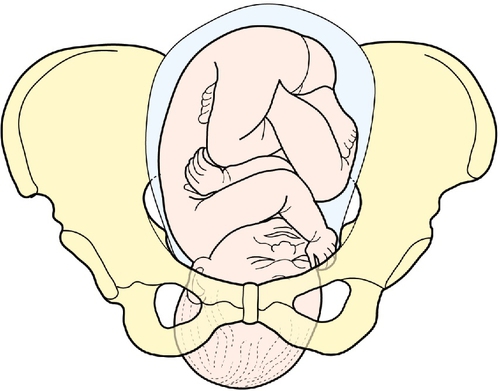

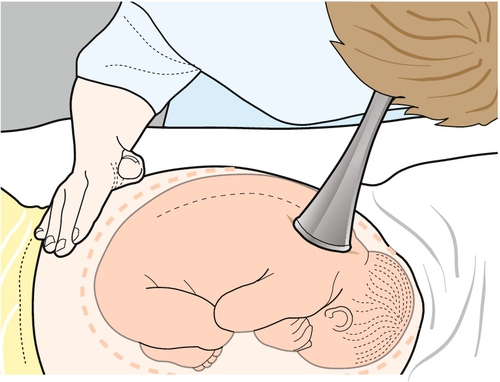

The next stage is to feel the uterus using gentle pressure of both hands, noting any irregularities, any tender areas and the two fetal ‘poles’, head and bottom. The ‘lie’ of the fetus refers to the axis of the poles in relation to the mother. It is usually longitudinal but can be transverse or oblique. The presentation refers to the part of the baby that is entering the pelvis. Generally, it is the head (cephalic) or the bottom (breech) but it can be the back or limbs (Figs 3.13–3.16). In twins, it should be possible to feel at least three fetal poles.

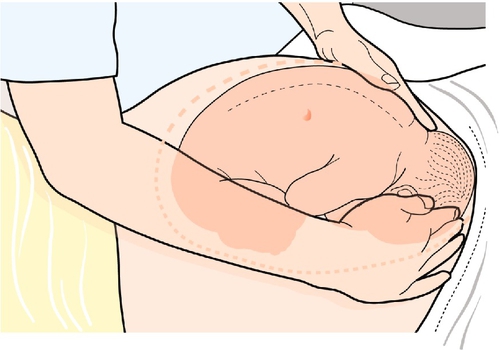

The ‘engagement’ of the head refers to how far into the pelvis it has moved (Figs 3.17–3.21). This may be palpated by turning to face the woman’s feet and pushing suprapubically, trying to ballot the head between the fingers. The descent can be likened to a setting sun and is recorded as ‘fifths palpable’. It is ‘engaged’ when the maximum diameter of the fetal head has passed through the pelvic brim. Therefore at three-fifths (3/5) palpable, it is not engaged but at two-fifths (2/5) palpable it is.

An attempt should be made to get an impression of the liquor volume, particularly if the SFH is abnormal. In oligohydramnios, fetal parts can often be felt easily, while in polyhydramnios the uterus is usually tense and fetal parts are difficult to feel. Also, feel for the back of the fetus. It is firmer than the limbs (the side of most movements) and lies to one side. This helps work out the position of the fetus and where to pick up the fetal heart, it runs at a rate of 110–150 bpm and is heard over the shoulder.

The fetal heart is heard using a USS transducer or a Pinard stethoscope (Figs 3.22 and 3.23) (see History boxes). To use a Pinard stethoscope, place the funnel over the anterior shoulder of the fetus and an ear at the other end, and listen carefully without holding on. It can be tricky, and is rather like listening to a clock ticking behind a waterfall. At the end of the examination, ensure that the woman is comfortable, cover her abdomen and help her to sit up.

Obstetrical vaginal examination

Vaginal examination is the cornerstone of intrapartum management, but is also a key skill in antenatal assessment. It is used in the diagnosis of pre-labour rupture of membranes and to assess pre-labour cervical change.

Although the diagnosis of membrane rupture is often made from the clinical history, a speculum examination is important for three reasons. The first is to look for evidence of liquor in the vagina. The technique is similar to gynaecological speculum examination, with careful aseptic technique. A pool of fluid, sometimes containing white flecks of vernix, can usually be seen in the posterior vagina or coming from the cervix on coughing. The second is to allow a high vaginal swab to be taken, looking particularly for pathogenic bacteria, notably group B β-haemolytic streptococci. The third is to allow a visual inspection of the cervix to avoid digital examination.

Digital examination assesses pre-labour cervical change in pre-term and post-term pregnancies. This helps determine those at risk of pre-term delivery and is useful in the management of labour induction. After abdominal palpation, the vaginal examination is performed in the same way as a gynaecological examination. In addition, however, it is important to note the ischial spines posterolaterally, as the ‘station’ or degree of descent, is made with reference to this point.

Feel for the cervix and note its position. Is it anterior or posterior and difficult to reach? Note its length. The cervix shortens from 3–4 cm until it is flush with the fetal head and does not protrude into the vagina. This is called effacement. What is its consistency? Is it soft like a cheek or hard like a nose? Feel for the os and how much it is dilated. Note if it is closed or whether one or two fingers can be inserted. The station of the presenting part is determined as above.

The cervix is assessed by the modified Bishop score (see Table 42.1). As the cervix ripens, it becomes softer, shorter, more anterior and more dilated, and the fetal head descends. As the onset of spontaneous labour approaches, the Bishop score increases.