CHAPTER 1 History and Evolution of Hip Surgery

Overview of the evolution of hip surgery

Other Procedures

Proximal femoral osteotomy

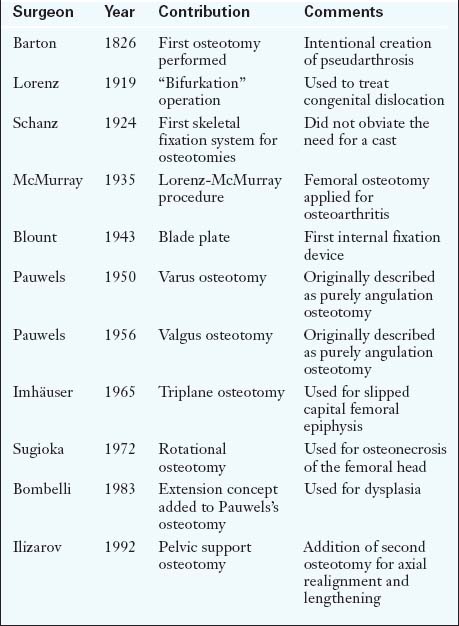

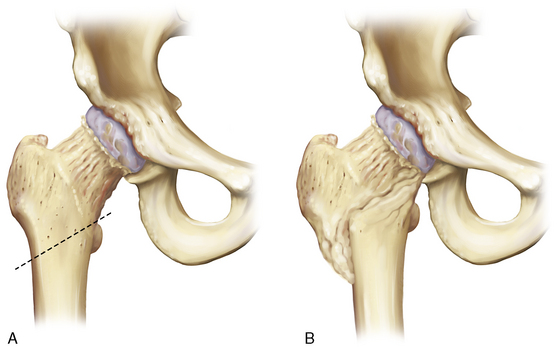

Early on, adult sequelae of developmental hip dysplasia were the most common indications for an ITO (Table 1-1). Early reports of realignment osteotomies of the proximal femur involved either displacement or angulation. Hip dysplasia was the first application of this procedure, although now it rarely constitutes an indication, at least for an isolated femoral osteotomy. Adolf Lorenz (1919) described his “bifurkation” operation, and Schanz (1922)—among others—also introduced a variation of Kirmission’s procedure, mainly for unreduced congenital dislocation of the hip. Both of these procedures were of the pelvic support osteotomy type. Lorenz outlined ten indications for his procedure, with advanced osteoarthritis being the eighth. In his report in 1935, McMurray from Liverpool adopted Lorenz’s procedure, and he is the one who popularized proximal femoral osteotomy for the treatment of osteoarthritis. The so-called Lorenz-McMurray procedure was described—but not performed in reality—as an excessively oblique cut (Figure 1-1). Although it was originally described as a purely displacement osteotomy, it did secondarily employ valgus angulation. McMurray believed that the primary mechanism of pain relief was the bypass of the proximal femur during the transmission of loads from the pelvis to the distal fragment. Displacement osteotomies were widely used in England, with Malkin (earlier) and Nissen (later) being their most eminent proponents.

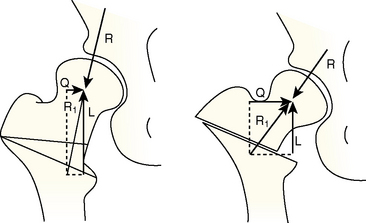

The prototype angulation osteotomy was described in 1950 by Pauwels, who designed a varus osteotomy above the lesser trochanter without displacement; he initially applied this procedure to young adults with hip dysplasia associated with the subluxation of a spherical femoral head. In 1956, he introduced valgus osteotomy for those hips that obtained improved congruity in adduction and for nonunited fractures of the femoral neck. About 10 years after the original description by Pauwels, the procedure came to include the medial displacement of the distal fragment (Figure 1-2).

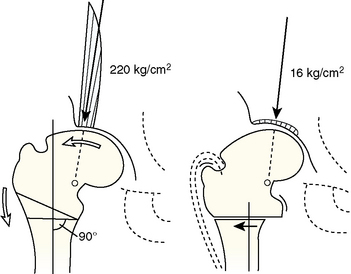

His ideas were taken a step further by Bombelli, who reached the same conclusions through a modified consideration of the primary hip forces. In addition to his theoretical model, Bombelli also modified Pauwels’s valgus osteotomy by adding extension in the sagittal plane for improved femoral head coverage in dysplasia, for the relief of flexion contracture, and for the correction of hyperlordosis. He also suggested that, in the case of a valgus osteotomy, one should exploit the inferomedial capital drop osteophyte (Figure 1-3) and put the lateral capsule to enough stretch to stimulate the formation of the roof osteophyte, both for the purpose of increasing the weight-bearing area of the joint.

Acetabular Osteotomy

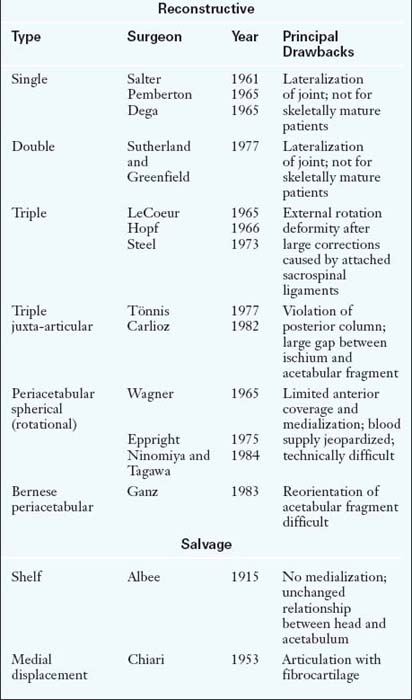

Much like femoral osteotomies, acetabular osteotomies are divided into reconstructive (e.g., redirectional, reshaping) procedures and salvage procedures. These operations are intended for patients whose main pathology is on the acetabular side; congruously dysplastic hips comprise the prototype indication for these osteotomies. Unlike osteoarthritis, for which improved congruence is the goal, dysplastic hips require improved coverage to reduce contact pressure within the joint. Numerous reconstructive pelvic osteotomies were devised during the twentieth century, with each trying to address the problems of the previously described procedures (Table 1-2).

Hip Arthroscopy

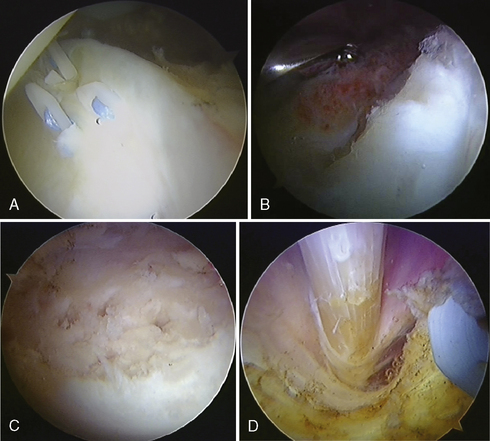

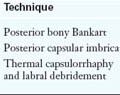

A common indication for hip arthroscopy has been the presence of loose bodies causing mechanical symptoms. In the absence of associated major structural abnormalities, hip arthroscopy is the preferred treatment for intra-articular disorders, with labral lesions being the most common. Other indications include extra-articular disorders that affect the iliopsoas tendon and bursa and the tensor fasciae latae and its adjacent trochanteric bursa (Figure 1-4). An endoscopically assisted technique for triple innominate osteotomy has also been described by Wall and colleagues. Clearly, the technique and applications of hip arthroscopy are still evolving.

Evolution of hip surgery in relation to specific conditions

Annotated references and suggested readings

Blount W.P. Blade-plate internal fixation for high femoral osteotomies. J Bone Joint Surg.. 1943;25:319-339.

Bombelli R., Santore R.F., Poss R. Mechanics of the normal and osteoarthritic hip: a new perspective. Clin Orthop.. 1984;182:69-78.

Brand R.A. Hip osteotomies: a biomechanical consideration. J Am Acad Orthop Surg.. 1997;5:282-291.

Byrd J.W.T., editor. Operative hip arthroscopy, 2nd ed, New York: Springer-Verlag, 2005.

Ezoe M., Naito M., Inoue T. The prevalence of acetabular retroversion among various disorders of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 2006;88:372-379.

Ganz R., Gill T.J., Gautier E., et al. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip: a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2001;83:1119-1124.

Ganz R., Klaue K., Vinh T.S., et al. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias: technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop.. 1988;232:26-36.

Harris W.H. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop.. 1986;213:20-33.

Jones R. The Classic: British Orthopaedic Association Symposium on the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip 1920. Clin Orthop.. 2005;441:4-6.

Klaue K., Durnin C.W., Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome: a clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 1991;73:423-429.

Millis M.B., Kim Y-J. Rationale of osteotomy and related procedures for hip preservation: a review. Clin Orthop.. 2002;405:108-121.

Parvizi J., Campfield A., Clohisy J.C., et al. Management of arthritis of the hip in the young adult. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2006;88:1279-1285.

Peltier L.F. A history of hip surgery. In: Callaghan J.J., Rosenberg A.G., Rubash H.E., editors. The adult hip. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1998:3-36.

Smith-Petersen M.N. Treatment of malum coxae senilis, old slipped upper femoral epiphysis, intrapelvic protrusion of the acetabulum, and coxa plana by means of acetabuloplasty. J Bone Joint Surg.. 1936;18:869-880.

Trousdale R.T. Acetabular osteotomy: indications and results. Clin Orthop.. 2004;429:182-187.