3 Histological Changes in the Aging Spine

Introduction

Back pain is one of the most common reasons for office visits to a physician. It accounts for 2% of all visits, surpassed only by routine examinations, diabetes, and hypertension.1 Back pain is a condition that predominantly affects the older population. Increased survival rates, better health care outcomes, and improved economic status will increase the number of older people in our society. At present, persons older than 65 years constitute 13% of our population. In 30 years, they will constitute 30% of the United States population, and by the year 2050 they will makeup 60% of the population.2 It is of paramount importance to recognize this trend of aging in the population and plan how best to fulfill the health needs of this growing part of our society.

Intervertebral Disk

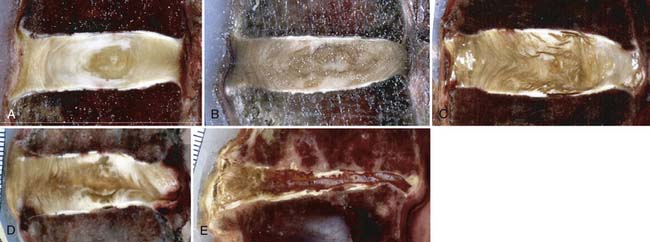

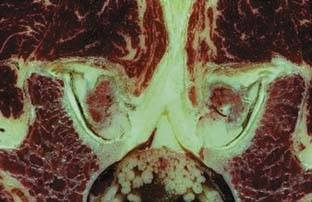

The intervertebral disks are remnants of the notochord and are interspersed between adjacent vertebral bodies of the spine except between the fused bodies of the sacrum and the coccyx. The intervertebral disks are composed of a circular ring of more resilient annulus fibrosus, which holds a central core of gelatinous material called the nucleus pulposus (Figure 3-1). Biochemically, both the annulus fibrosus and the nucleus pulposus contain proteoglycans in addition to water. The amount of water varies and is responsible for their varied characteristics and, consequently, their functions. The intervertebral disks derive their nutrition by diffusion across vertebral endplates. As the rate of permeability decreases with aging, the health of the disk is threatened.

FIGURE 3-1 Intervertebral disk. Outer annulus fibrosus surrounding inner nucleus pulposus.

(Courtesy of Wolfgang Rauschning, MD.)

Due to decreased turgor and nutrition of the disks, radial and concentric fissures appear in the initial phases of degeneration. The normal avascular disks may develop microvascular capillaries at the periphery of the annulus fibrosus as a compensatory mechanism for decreased nutrition (Figure 3-2). However, this impaired neovascularization is detrimental, contributes to microedema, and exposes the disks to the body’s immune cells for the first time in adult life. Also, there is dissection of the microstructural organization of the annulus fibrosus. The radial fissures eventually enlarge and follow the path of least resistance posterolaterally in relation to the vertebral bodies and overlying the intervertebral foramina. In the late stages of disk degeneration, the nucleus pulposus tracks out over the intervertebral foramina and can compress the exiting spinal nerve, potentially causing symptoms of radiculopathy.

FIGURE 3-2 Neovascularization at periphery of an annular tear.

(Courtesy of Wolfgang Rauschning, MD.)

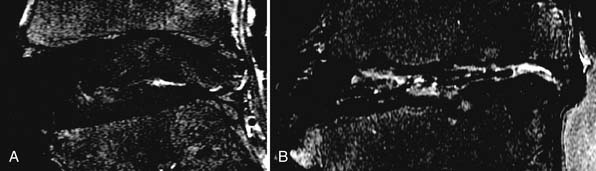

Plain x-ray films show decreased intervertebral spaces, accompanied by deformed endplates and osteophyte formation. However, these are terminal changes and not helpful from an early diagnostic point of view. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is regarded as the gold standard for early detection of disk degeneration. Disk desiccation (unhealthy disks are darker due to lesser water content), disk bulge due to deformed annulus fibrosus, and radial tears within the disk are early makers of disk degeneration3 (Figures 3-3, 3-4). Novel imaging techniques such as MR spectroscopy to measure lactic acid within the disk (an early sign of disk degeneration), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) for measuring water content within the disk, and functional MRI (fMRI) for task dependent signal intensity changes have been proposed and warrant further study.

Vertebral Bodies

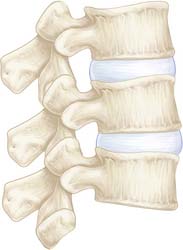

The vertebral bodies are the primary support of the spinal cord and are osseous in nature. They differentiate from the segmental sclerotomes in embryological life and form the framework to support the spinal cord and its vascular supply. Vertebral bodies are composed of cancellous bone and are best adapted to resist compressive loads (Figure 3-5). However, this same property predisposes the cancellous bones to accelerated changes during aging. They are supplied by a rich network of vascular channels at low pressure, compared to cortical bones found elsewhere in the body which have haversian canals with high-pressure vascular channels. The increased vascularity in vertebral bodies, coupled with a low pressure system, increases their surface area ratio and sensitizes them to minute changes in hormones and other factors in the extracellular fluids. On a biochemical level, the cancellous bone is a lattice network composed of collagen and noncollagen proteins and calcium hydroxyapatite. The osteoid framework is laid down by osteoblasts and resorbed and restructured by osteoclasts, both of which are under the influence of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and calcitonin.

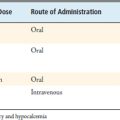

The bone density is maximal at 25 years of age and decreases with aging. Osteoporosis is characterized by decreased bone formation and mineralization as well as decreased bone density.4 This effect is multifactorial in nature. During aging, there is a decrease in absorption and assimilation of nutrients including calcium and vitamin D. Decreased conversion of vitamin D2 to vitamin D3 in kidneys decreases the mineralized components of the bone.5 There is also a general decline in production of various hormones influencing bone formation including PTH, estrogen, and glucocorticoids, which decrease osteoblastic activity. Furthermore, there is an increase in IL-6, TNF-α, and other chemokines due to impaired immunity which increases osteoclastic activity. In addition, there is usually an overall decline in physical activity and exercise and decreased quality of diet in the elderly. All these factors together precipitate an osteopenic state.

Patients usually present with overwhelming back pain brought on after sudden physical activity, after lifting objects, or after coughing or bending. Plain radiographs show a decreased vertebral body height, decreased bone density (a 30% reduction in mineralization from baseline is required to visualize osteopenia on plain radiographs), and compression fractures (Figure 3-6). The bone density scan, also known as the dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan, is an enhanced form of x-ray technology and the gold standard for imaging osteoporosis. The results of a DEXA scan are expressed as a T-score, which is an index of standard deviation. A T-score of less than −2.5 is significant for osteoporosis. Quantitative CT is an alternative imaging modality but requires high-resolution CT scanners and may not be available at all centers.6 High-resolution MR imaging has been proposed and is focused on assessing bone structure directly rather than only assessing mineralization.7

Facet Joints

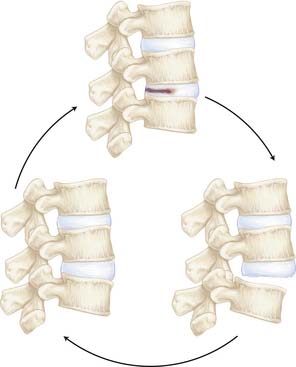

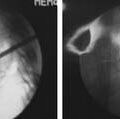

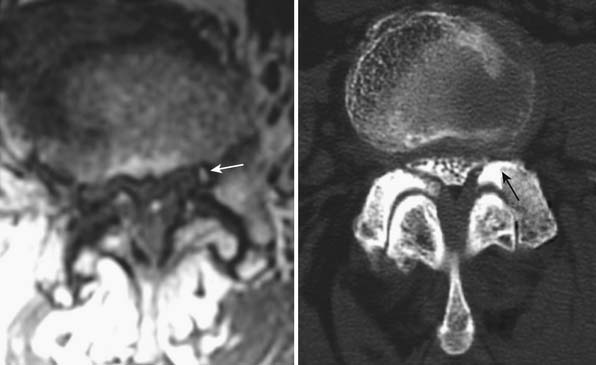

Facet joints are the only true synovial joints within the vertebral column. The facet joint is located between two adjacent vertebral bodies with the upper facet facing downwards and medially and the lower facet facing upward and laterally. The facets articulate with a thin interspersed cartilage and are surrounded by a synovial sac and innervated by rich nerve endings (Figure 3-7). In a healthy young individual, the intervertebral disk is the anterior load-bearing structure and the facet is the posterior load-bearing structure. Hence facet joints are referred to as the three-joint complex, with two facets and the intervertebral disk (Figure 3-8). These joints allow flexion-extension and some torsion of the spine.8 During aging, facet joint pathology is always secondary to disk degeneration. Increased load is subsequently transferred to the facet joints, which were designed for small load-bearing capacity. This increased load causes facet joint degeneration. The cartilage is the first structure to be affected, with resultant synovial inflammation, joint space narrowing, and osteophyte formation resulting in central or foraminal stenosis and spondylolisthesis (Figures 3-9, 3-10). The resulting inflammation causes irritation of the nociceptive nerve endings, causing back pain sometimes referred to as “facet joint syndrome.”9

FIGURE 3-7 Facet joints are composed of synovial joints lined with synovium and articular cartilage.

(Courtesy of Wolfgang Rauschning, MD.)

FIGURE 3-10 MRI and CT evidence of foraminal and central stenosis as a result of facet osteophyte development.

On plain radiographs, sclerosis and osteophyte formation can be visualized in facet joints, demonstrating late stages of degeneration. MR imaging of the cartilage revealing focal erosions may be the earliest sign of facet degeneration and may be amenable to rescue measures. Facet hypertrophy, apophyseal malalignment, and osteophyte formation may be recognized on CT scans.10

Muscles and Ligaments

The intrinsic and extrinsic muscles, along with the ligaments, maintain the spine at optimal tension and maintain the normal physiological primary curvatures.11 The ligamentum flavum connects adjacent vertebrae along the anterior edge of the lamina. It is primarily composed of elastin, and allows flexion and extension. The elastin content is responsible for the tensile strength of the ligamentum flavum. During aging, the muscles lose the ability to attain tetanic contractions, have decreased contractile force, and undergo atrophy. This atrophy is due to a decline in nutrition and hormonal status, in addition to decreased physical activity. Microscopically the muscles show decreased collagen fiber content and increased fatty infiltration. The ligamentum flavum has decreased elastin content and becomes lax and bulging, destabilizing the vertebral column.12 These changes predispose the aging spine to disk degeneration, compression fractures, and spinal stenosis by altering the normal curvature and the normal tension within the spine.

1. Martin B.I., Deyo R.A., Mirza S.K., et al. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. Jama. 2008;299:656-664.

2. Turkulov V., Madle-Samardzija N., Niciforovic-Surkovic O., Gavrancic C. [Demographic aspects of aging]. Med Pregl. 2007;60:247-250.

3. Johannessen W., Auerbach J.D., Wheaton A.J., et al. Assessment of human disc degeneration and proteoglycan content using T1rho-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 2006;31:1253-1257.

4. Lee Y.L., Yip K.M. The osteoporotic spine. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1996:91-97.

5. Nickolas T.L., Leonard M.B., Shane E. Chronic kidney disease and bone fracture: a growing concern. Kidney international. 2008.

6. Shi H., Scarfe W.C., Farman A.G. Three-dimensional reconstruction of individual cervical vertebrae from cone-beam computed-tomography images. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:426-432.

7. Zaia A., Eleonori R., Maponi P., Rossi R., Murri R. MR imaging and osteoporosis: fractal lacunarity analysis of trabecular bone. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2006;10:484-489.

8. Fujiwara A., Tamai K., Yamato M., et al. The relationship between facet joint osteoarthritis and disc degeneration of the lumbar spine: an MRI study. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:396-401.

9. Raj P.P. Intervertebral disc: anatomy-physiology-pathophysiology-treatment. Pain Pract. 2008;8:18-44.

10. Barry M., Livesley P. Facet joint hypertrophy: the cross-sectional area of the superior articular process of L4 and L5. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:121-124.

11. Yamada M., Tohno Y., Tohno S., et al. Age-related changes of elements and relationships among elements in human tendons and ligaments. Biological trace element research. 2004;98:129-142.

12. Kosaka H., Sairyo K., Biyani A., et al. Pathomechanism of loss of elasticity and hypertrophy of lumbar ligamentum flavum in elderly patients with lumbar spinal canal stenosis. Spine. 2007;32:2805-2811.