Chapter 501 Histiocytosis Syndromes of Childhood

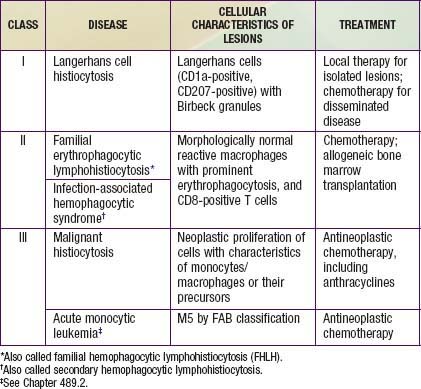

The childhood histiocytoses constitute a diverse group of disorders, which, although individually rare, may be severe in their clinical expression. These disorders are grouped together because they have in common a prominent proliferation or accumulation of cells of the monocyte-macrophage system of bone marrow origin. Although these disorders sometimes are difficult to distinguish clinically, accurate diagnosis is essential nevertheless for facilitating progress in treatment. A systematic classification of the childhood histiocytoses is based on histopathologic findings (Table 501-1). A thorough, comprehensive evaluation of a biopsy specimen obtained at the time of diagnosis is essential. This evaluation includes studies such as electron microscopy and immunsotaining that may require special sample processing.

Classification and Pathology

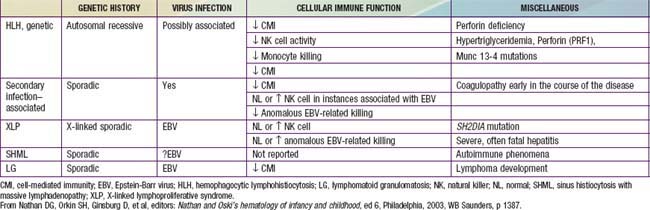

In contrast to the prominence of an antigen-presenting cell (the Langerhans cell) in the class I histiocytoses, the class II histiocytoses are nonmalignant proliferative disorders that are characterized by accumulation of antigen-processing cells (macrophages). Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytoses (HLH) are the result of uncontrolled hemophagocytosis and uncontrolled activation (upregulation) of inflammatory cytokines similar to the macrophage activation syndrome (see Table 149-5). Tissue infiltration by activated CD8 T lymphocytes, activated macrophages, and hypercytokinemia are classic features. With the characteristic morphology of normal macrophages by light microscopy, these phagocytic cells are negative for the markers (Birbeck granules, CD1a-positivity, CD207-positivity) characteristic of the cells found in LCH. The 2 major diseases among the class II histiocytoses have indistinguishable pathologic findings. One is familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHLH), previously called familial erythrophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FEL), which is the only inherited form of histiocytosis and is autosomal recessive. Some specific genes involved with FEL include mutations of perforin, Munc 13-4, and Syntaxin-11 and all are related to pathways of granule-mediated cellular cytotoxicity. The other is the infection-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (IAHS), also called secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (Table 501-2). Both diseases are characterized by disseminated lesions that involve many organ systems. The lesions are characterized by infiltration of the involved organ with activated phagocytic macrophages and lymphocytes, in which the lymphocyte (cytolytic pathway) defects are considered to be the primary abnormality. These diseases are grouped together under the term hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (Table 501-3).

Table 501-2 INFECTIONS ASSOCIATED WITH HEMOPHAGOCYTIC SYNDROME

VIRAL

BACTERIAL

FUNGAL

MYCOBACTERIAL

RICKETTSIAL

PARASITIC

From Nathan DG, Orkin SH, Ginsburg D, et al, editors: Nathan and Oski’s hematology of infancy and childhood, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2003, WB Saunders, p 1381.

The class III histiocytoses, in contrast, are unequivocal malignancies of cells of monocyte-macrophage lineage. By this definition, acute monocytic leukemia and true malignant histiocytosis are included among the class III histiocytoses (Chapter 489). The existence of neoplasms of Langerhans cells is controversial. Some cases of LCH demonstrate clonality.

501.1 Class I Histiocytoses

Clinical Manifestations

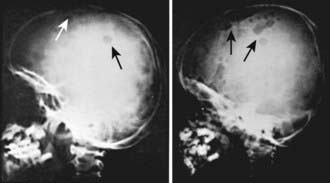

LCH has an extremely variable presentation. The skeleton is involved in 80% of patients and may be the only affected site, especially in children >5 yr of age. Bone lesions may be single or multiple and are seen most commonly in the skull (Fig. 501-1). Other sites include the pelvis, femur, vertebra, maxilla, and mandible. They may be asymptomatic or associated with pain and local swelling. Involvement of the spine may result in collapse of the vertebral body, which can be seen radiographically, and may cause secondary compression of the spinal cord. In flat and long bones, osteolytic lesions with sharp borders occur and no evidence exists of reactive new bone formation until the lesions begin to heal. Lesions that involve weight-bearing long bones may result in pathologic fractures. Chronically draining, infected ears are commonly associated with destruction in the mastoid area. Bone destruction in the mandible and maxilla may result in teeth that, on radiographs, appear to be free floating. With response to therapy, healing may be complete.

Treatment and Prognosis

The clinical course of single-system disease (usually bone, lymph node, or skin) generally is benign, with a high chance of spontaneous remission. Therefore, treatment should be minimal and should be directed at arresting the progression of a bone lesion that could result in permanent damage before it resolves spontaneously. Curettage or, less often, low-dose local radiation therapy (5-6 Gy) may accomplish this goal. Multisystem disease, in contrast, should be treated with systemic multiagent chemotherapy. Several different regimens have been proposed, but a central element is the inclusion of either vinblastine or etoposide, both of which have been found to be very effective in treating LCH. Treatment of multisystem LCH includes therapy with multiple agents, designed to reduce reactivation of disease and long-term consequences. The response rate to therapy, contrary to previous belief, is high, and mortality in severe LCH has been substantially reduced by multiagent chemotherapy, especially if the diagnosis is made accurately and expeditiously. Experimental therapies, suggested only for unresponsive disease (often in very young children with multisystem disease and organ dysfunction who have not responded to multiagent initial treatment), include immunosuppressive therapy with cyclosporine/antithymocyte globulin and possibly certain new agents and modalities, such as imatinib, 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine, and stem cell transplantation. Late (fibrotic) complications, whether hepatic or pulmonary, are irreversible and require organ transplantation to be definitively treated. Current treatment approaches and experimental protocols for both class I and class II histiocytoses can be obtained at the website for the Histiocyte Society: www.histiocytesociety.org.

Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156.

Gadner H, Grois N, Pötschger U, et al. Improved outcome in multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis is associated with therapy intensification. Blood. 2008;111:2556-2562.

Grois N, Fahrner B, Arceci RJ, et al. Central nervous system disease in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2010;156(6):873-881.

Hait E, Liang M, Degar B, et al. Gastrointestinal tract involvement in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: case report and literature review. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1593-e1599.

Minkov M, Steiner M, Potschger U, et al. Reactivations in multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis: data of the international LCH registry. J Pediatr. 2008;153:700-705.

Mohr MR, Sholtzow M, Bevan HE, et al. Exploring the differential diagnosis of hemorrhagic vesicopustules in a newborn. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e226-e230.

Salotti JA, Nanduri V, Pearce MS, et al. Incidence and clinical features of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in the UK and Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:376-380.

Weitzman S, Egeler M. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: update for the pediatrician. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:23-28.

Wnorowski M, Prosch H, Prayer D, et al. Pattern and course of neurodegeneration in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2008;153:127-132.

501.2 Class II Histiocytoses: Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)

(See earlier section, Classification and Pathology.)

Clinical Manifestations

The major forms of HLH, familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHLF) and secondary HLH, have a remarkably similar presentation consisting of a generalized disease process, most often with fever, maculopapular and/or petechial rash, weight loss, and irritability (Tables 501-4 and 501-5). FHLH also is characterized by severe immunodeficiency. Children with FHLH frequently are <4 yr of age, and children with secondary HLH may present at an older age, but both forms are now recognized as presenting at any age. Physical examination often reveals hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, respiratory distress, and symptoms of CNS involvement that are not unlike those of aseptic meningitis. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in CNS involvement of FHLH is characterized by CSF cells that are the same phagocytic macrophages found in the peripheral blood or bone marrow. The definitive diagnosis is based on a set of criteria recently formulated by the Histiocyte Society: It can be made either on the basis of a molecular (genetic) defect (see later) or on the pathologic findings of hemophagocytosis in bone marrow biopsy and/or clinical findings of fever, splenomegaly, and associated laboratory findings (in both forms of HLH), including hyperlipidemia, hypofibrinogenemia, elevated levels of hepatic enzymes, extremely elevated levels of circulating soluble interleukin-2 receptors released by the activated lymphocytes, very high levels of serum ferritin (often >10,000), and cytopenias (especially pancytopenia from hemophagocytosis in the marrow). No absolute clinical or laboratory distinction can be made between FHLH and secondary HLH, although genetic markers for FHLH can complement a positive family history for other affected children. HLH may be present in the absence of genetic mutations of the perforin or Munc 13-4 genes, and can be diagnosed by the presence of 5 of the following: fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia of 2 cell lines, hypertriglyceridemia or hypofibrinogenemia, hyperferritinemia, elevated soluble CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor), reduced or absent NK cells, and bone marrow, CSF, or lymph node evidence of hemophagocytosis.

Table 501-4 DIAGNOSTIC GUIDELINES FOR HLH

The diagnosis of HLH is established by fulfilling 1 or 2 of the following criteria:

From Verbsky JW, Grossman WJ: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: diagnosis, pathophysiology, treatment, and future perspectives, Ann Med 38:20–31, 2006, p 21, Table 1. (Note: Adapted from Treatment Protocol of the 2nd International HLH Study, 2004.)

Table 501-5 SPECTRUM OF DISEASES CHARACTERIZED BY HEMOPHAGOCYTOSIS

PRIMARY HLH

SECONDARY HLH

INFECTION ASSOCIATED HLH

MALIGNANCY ASSOCIATED HLH

MACROPHAGE ACTIVATION SYNDROME (MAS) ASSOCIATED WITH AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE

CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HHV, human herpesvirus; VZV, Varicella-zoster virus.

From Verbsky JW, Grossman WJ: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: diagnosis, pathophysiology, treatment, and future perspectives, Ann Med 38:20–31, 2006, p 22, Table 2.

Treatment and Prognosis

In contrast, in secondary HLH, when an infection can be documented and effectively treated, the prognosis may be excellent without any other specific treatment. However, when a treatable infection cannot be documented, which is the case in most patients presumed to have secondary HLH, the prognosis may be as poor as that of FHLH, and an identical chemotherapeutic approach, including etoposide, is recommended, even in the face of cytopenias. It is theorized that in both cases, by its cytotoxic effect on macrophages, etoposide interrupts cytokine production, the hemophagocytic process, and the accumulation of macrophages, all of which may contribute to the pathogenesis of IAHS. A broad spectrum of infectious agents, viruses (e.g., cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6), fungi, protozoa, and bacteria may trigger secondary HLH, usually in the setting of immunodeficiency (see Table 501-2). A thorough evaluation for infection should be undertaken in immunodeficient patients with hemophagocytosis. Rarely, the same syndrome may be identified in conjunction with a rheumatologic disorder (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, Kawasaki disease) or a neoplasm (leukemia); in this case, treatment of the underlying disease may cause resolution of the hemophagocytosis. In some patients, interferon and intravenous immunoglobulin have been effective.

Cooper N, Rao K, Webb G, et al. The use of reduced-intensity stem cell transplantation in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:S47-S50.

Filipovich A. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and other hemophagocytic disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:293-313.

Domachowske JB. Infectious triggers of hemophagocytic syndrome in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:1067-1068.

Janka G. Familial and acquired haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:95-109.

Lau S, Chu P, Weiss M. Immunohistochemical expression of langerin in Langerhans cell histiocytic disorders. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:615-619.

Lee WI, Chen SH, Hung IJ, et al. Clinical aspects, immunologic assessment, and genetic analysis in Taiwanese children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:30-34.

Mahlaoui N, Iuachee-Chardin M, de Saint Basile G, et al. Immunotherapy of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with antithymocyte globulins: a single-center retrospective report of 38 patients. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e622-e628.

Mischler M, Fleming GM, Shanley TP, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and X-linked lymphoproliferative disease: a mimicker of sepsis in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1212-e1218.

Ouachee-Chardin M, Elie C, de Saint Basile G, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a single-center report of 48 patients. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e743-e750.

Suzuki N, Morimoto A, Ohga S, et al. Characteristics of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in neonates: a nationwide survey of Japan. J Pediatr. 2009;155:235-238.

501.3 Class III Histiocytoses

Acute monocytic leukemia and true malignant histiocytosis are included among the class III histiocytoses (Chapter 484), because they are unequivocal malignancies of the monocyte-macrophage lineage.

Coury F, Annels N, Rivollier A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis reveals a new IL-17A-dependent pathway of dendritic cell fusion. Nat Med. 2008;14:81-87.

Filipovich A. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and other hemophagocytic disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:293-313.

Feldmann J, Callebaut I, Raposo G, et al. Munc 13–4 is essential for cytolytic granules fusion and is mutated on a form of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL3). Cell. 2003;115:461-473.

Lee SM, Sumegi J, Villanueva J, et al. Patients of African ancestry with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis share a common haplotype of PRFI with a 50 delt mutation. J Pediatr. 2006;149:134-137.

Valladeau J, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Saeland S. Langerin/CD207 sheds light on formation of Birbeck granules and their possible function in Langerhans cells. Immunol Res. 2003;28:93-107.

Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society. Histiocytosis syndromes in childhood. Lancet. 1987;1:208-209.