HIP

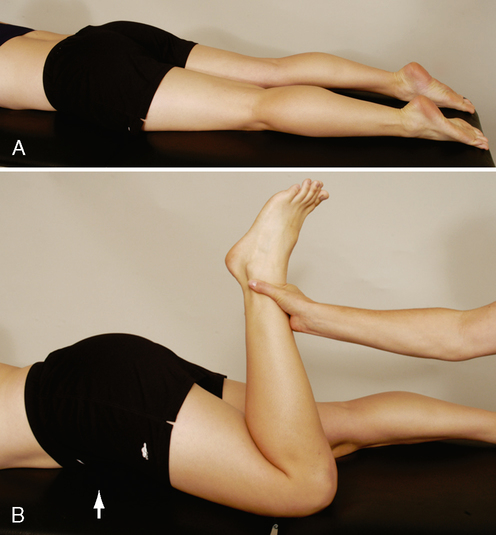

SPECIAL TESTS FOR HIP PATHOLOGY8–13

Relevant Special Tests

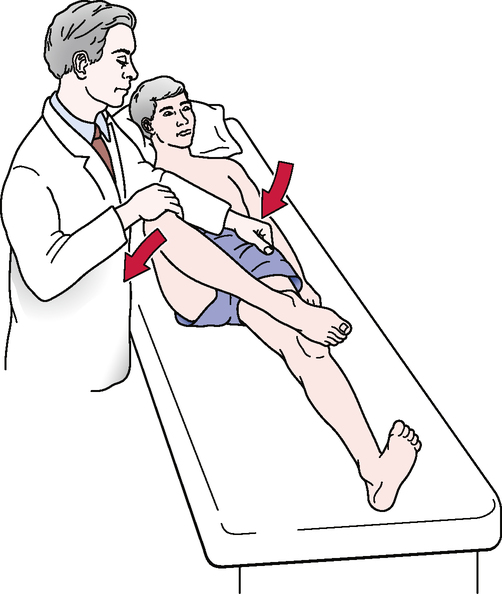

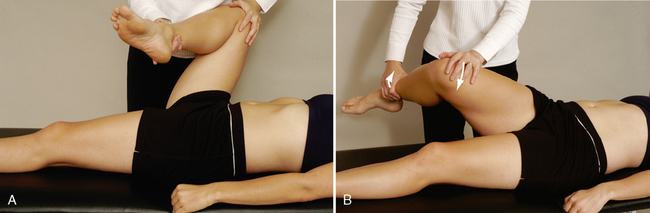

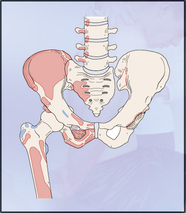

Patrick’s test (flexion, abduction, and external rotation [FABER] or figure-four test)

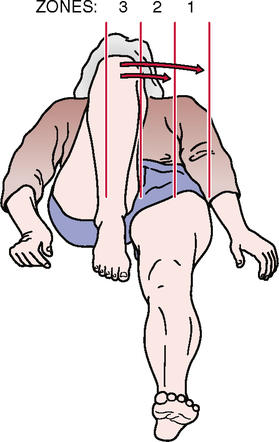

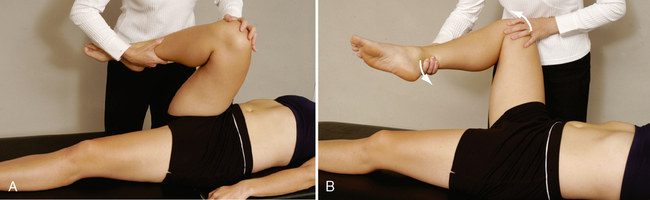

Anterior labral tear test (flexion, adduction, and internal rotation [FADDIR] test)

Epidemiology and Demographics

• Osteoarthritis affects 10% to 25% of the population over age 55.

• Osteonecrosis can occur in people of any age, but it is most common in people in their 30s, 40s, and 50s.

• In children, the most common cause of hip pain is acute transient synovitis. The incidence of slipped capital femoral epiphysis is about 6.1 per 10,000 in boys and 3 per 10,000 in girls. The incidence of Leg!g-Calvé-Perthes disease is about 1.5 to 5 per 10,000.

• In newborns, the prevalence of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) has been reported in screened populations at rates of 2.5 to 20 per 1000 births; however, it reaches 40 to 90 per 1000 births in some communities.

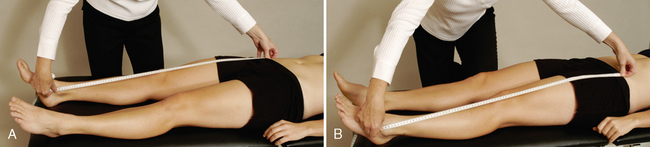

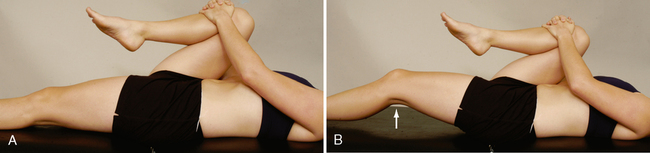

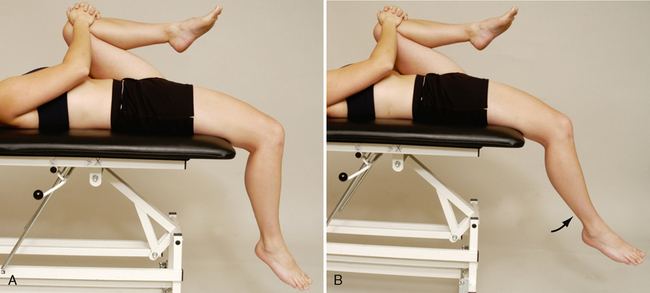

SPECIAL TESTS FOR LEG LENGTH

Relevant Special Tests

Definition

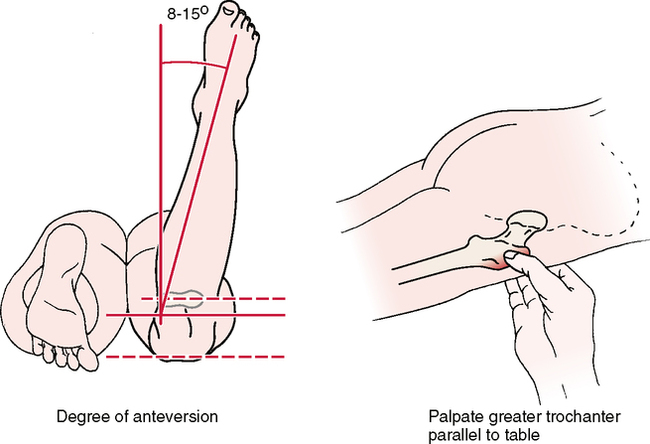

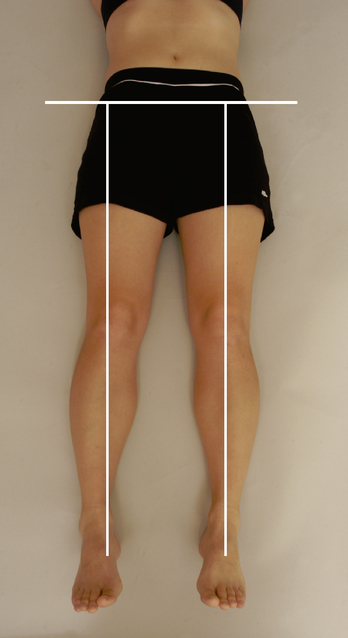

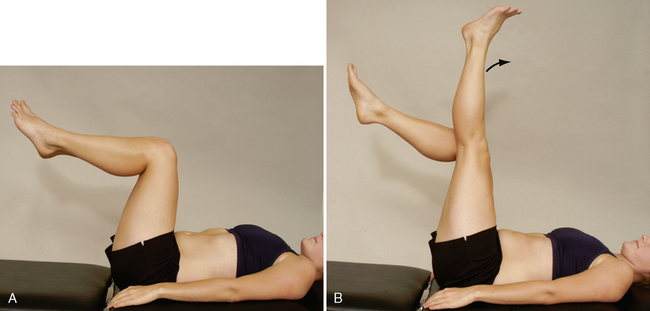

A leg length discrepancy is the difference in the longitudinal length of one leg compared with the other. Leg length discrepancies can be classified in two ways: as actual (true) leg length discrepancies or as apparent (functional) leg length discrepancies. In true leg length discrepancies, the length of one leg is truly different from the length of the other leg. In functional leg length discrepancies, one leg appears different from the other, but when the two legs are measured, the lengths are identical. The apparent length discrepancy can be caused by biomechanical factors (e.g., pelvic rotation) or foot pronation (see Table 9-1).

Epidemiology and Demographics

Freiberg30 studied patients with low back pain and discovered that those with a leg length discrepancy greater than 15 mm were five times more likely to have low back pain. Hip and sciatic pain occurred in the longer leg 78% of the time. In patients with leg length discrepancies greater than 3 cm, an asymmetrical lateral side bend of the spine occurs on the side of the longer leg. This results in abnormal loading mechanics of the spine. Leg length discrepancies of this magnitude are present in 40% of the general population.31

ten Brinke et al.31 reported that in 64 (62%) of 104 patients with a leg length discrepancy of 1 mm or more, the back pain radiated into the shorter leg.

Relevant Signs and Symptoms

• Leg length differences themselves are not usually painful.

• Difference is clinically relevant as a contributing cause of symptoms and pathological conditions in other regions, such as the lumbar spine, pelvis, sacroiliac joint, or lower extremity.

• An objective examination of any of these regions should include an examination of leg length.