Hernias and other groin problems

Introduction

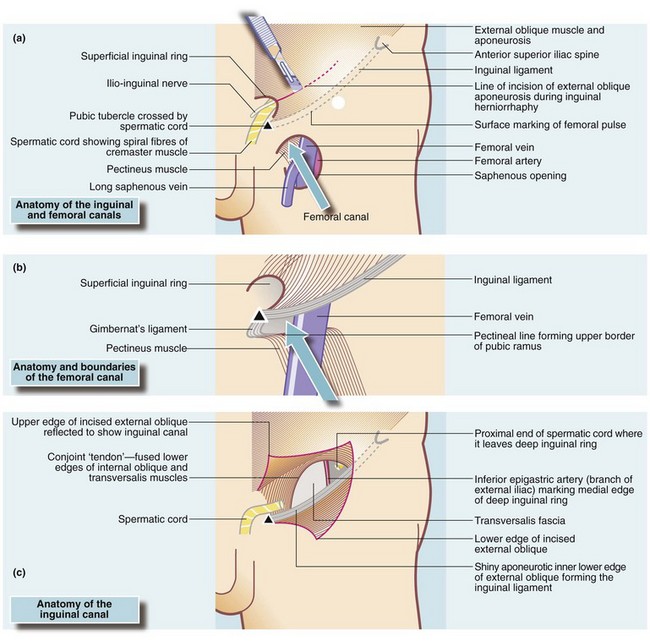

The anatomy of the groin provides a good starting point for understanding surgical problems in this area and is explained in Figure 32.1.

Fig. 32.1 Structure of the inguinal and femoral canals

(a) The entire groin area. The surface marking of the femoral pulse is shown, midway between the pubic symphysis and the anterior superior iliac spine; the deep ring lies 2.5 cm above it. (b) Structure of the femoral canal—the abdominal opening seen from below. (c) Structure of the inguinal canal. The inguinal canal displayed by incising the anterior wall (external oblique aponeurosis) as in the first stage of open repair; the spermatic cord has been removed for clarity

Lumps in the groin

• Examine the patient both standing and lying

• Examine for the presence of a cough impulse and test the reducibility of the lump

• Demonstrate the relationship of the origin of the lump to the inguinal ligament and the pubic tubercle

Position for examination

The patient must first be examined whilst standing, which increases intra-abdominal pressure, making any hernia more visible. Ask the patient to cough while palpating the lump: intra-abdominal pressure is thus transmitted through the abdominal wall and an expansile cough impulse is felt in a hernia. Small inguinal hernias may reduce on lying down, and a scrotal varicocoele (see Ch. 33) will empty.

Consistency and reducibility

Hernias are usually soft and ‘squishy’ but the most reliable diagnostic sign is if the lump reduces when the patient lies flat or can be reduced by gentle manipulation by patient or clinician. Most inguinal hernias are at least partly reducible, although longstanding hernias gradually become irreducible because of adhesions within the sac. These are said to be incarcerated, i.e. chronically irreducible. In contrast, femoral hernias are nearly always irreducible and have no cough impulse as the femoral canal is so narrow (see Table 32.1).

Table 32.1

Summary of groin lumps and swellings and their clinical features

| Disorder | Anatomical/developmental basis | Clinical features |

| a. Inguinal hernia Direct |

Simple bulging of abdominal contents resulting from inadequate support by weak or ruptured posterior wall of inguinal canal (transversalis fascia) | Discomfort; lump usually disappears on lying down; risk of incarceration if large but low risk of strangulation |

| Indirect | Passage of abdominal contents, often including bowel, through inguinal canal towards scrotum or labium majus | Potential for incarceration and strangulation; much more common in men |

| b. Femoral hernia | Abdominal contents, often including bowel, migrate into femoral canal | Rarely has a cough impulse; rarely reducible; high rate of strangulation; more common in women |

| c. Inguinal lymphadenopathy | Inguinal nodes drain lower limb, abdominal wall below umbilicus, anal canal, scrotal skin, penis (but not testes, which drain to para-aortic and para-iliac nodes) | Enlarged nodes indicate infection, lymphoma or metastases from primary lesion in drainage area |

| d. Saphena varix | Dilatation of long saphenous vein superficial to deep fascia before it enters the femoral vein | Can be mistaken for femoral hernia but empties on pressure and disappears on lying down, unlike femoral hernia; varicose veins present in the leg |

| e. Femoral artery aneurysm | Dilatation of common femoral artery just below inguinal ligament | Found in patients over 65 years, mostly male; classic clinical sign is expansile pulsation; could be mistaken for femoral hernia |

| f. Psoas abscess | Classically, a tuberculous abscess of lumbar vertebra tracking down inside sheath of psoas muscle; occasionally a pyogenic abscess originating within the abdomen presents via the same route | TB presents as swelling or ‘cold abscess’ below inguinal ligament; rare nowadays but may be confused with lymph nodes; pyogenic abscess typically ‘hot’; rarely may be due to abscess from renal stones |

Relationship to the inguinal ligament

The site of the lump in relation to the inguinal ligament needs to be identified. The ligament is not visible but stretches between two palpable bony prominences, the anterior superior iliac spine laterally and the pubic tubercle medially (see Fig. 32.1a). The pubic tubercle is higher than might be imagined from the skin contour, lying 2–3 cm above the groin crease. The iliac spine is easy to locate but the pubic tubercle can be difficult, especially in obese patients. It is best found by palpating along the upper border of the pubic symphysis, outwards from the midline (care is needed in the male as the spermatic cord can be tender where it crosses the pubic tubercle).

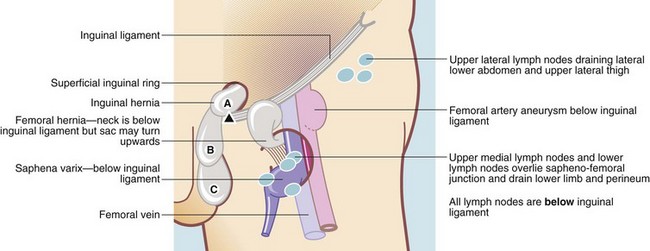

As shown in Figure 32.2, inguinal hernias always originate above the inguinal ligament, whereas femoral hernias, saphena varices and femoral artery aneurysms always arise below it. Enlarged inguinal lymph nodes are usually situated below the inguinal ligament.

Fig. 32.2 Significance of the relationship of groin lumps to the inguinal ligament

A, B and C are stages in the enlargement of an indirect inguinal hernia. Note that the neck is above the inguinal ligament. A direct inguinal hernia enlarges forwards in position A, but occasionally extends into the scrotum

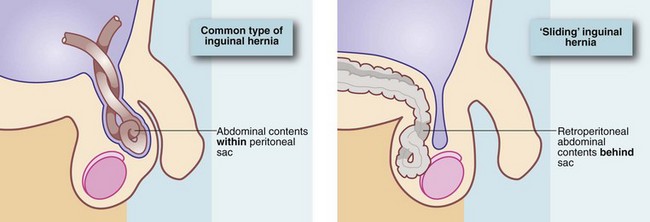

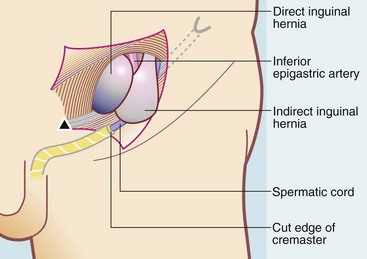

Direct and indirect inguinal hernias (Fig. 32.3)

Distinguishing between direct and indirect inguinal hernias may be clinically difficult but it is a useful exercise in eliciting clinical signs and frequently comes up in student examinations! By definition, an indirect inguinal hernia is one in which the hernial sac lies within the spermatic cord, leaving the abdomen via the deep (internal) inguinal ring to pass along the inguinal canal, exiting through the superficial (external) ring. Thus, if the hernia can be completely reduced, finger pressure over the deep ring will prevent it reappearing on coughing (the deep ring is midway between the pubic symphysis and the pubic tubercle, 2.5 cm above the femoral pulse; see Fig. 32.1a). In contrast, a direct inguinal hernia leaves the abdomen through a weakness or split in the transversalis fascia, the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, emerging directly through the superficial ring and cannot be controlled by digital pressure over the deep ring. In practice, this test is often unreliable. The patient’s age is perhaps the most useful indicator of the likely type of inguinal hernia, with indirect hernias most frequent under the age of 50 and direct hernias more common after that age.

Fig. 32.3 Direct and indirect inguinal hernias

A direct inguinal hernia bulges medially to the inferior epigastric artery and is not usually attached to the spermatic cord. An indirect inguinal hernia leaves the deep inguinal ring lateral to the artery and lies within the cremaster muscle covering the cord

Inguinal hernia

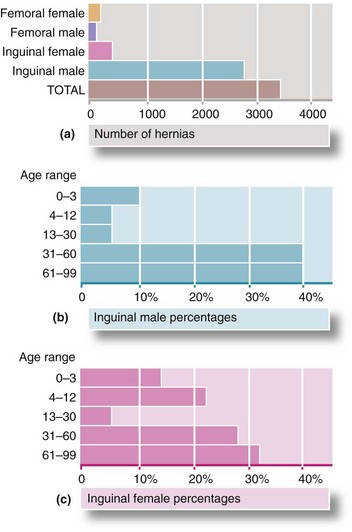

As shown in Figure 32.4, inguinal hernias in males are by far the most common type of groin hernia. Inguinal hernias occur eight times more often in males because of the abdominal wall deficiency caused by testicular descent. Femoral hernias are rare in males, comprising only 2.5% of groin hernias. Even in females, inguinal hernias are the most frequent (twice as common as femorals). Femoral hernias are twice as common in females as in males.

Fig. 32.4 Relative annual incidence of inguinal and femoral hernias in East Anglia (UK)

(a) Number of hernias by type and (b) Incidence of inguinal hernias in males by age. (c) Incidence of inguinal hernias in females by age

Anatomical considerations

The surgical anatomy of the inguinal canal is shown in Figure 32.1c. The external oblique aponeurosis (or fascia) forms the anterior wall of the inguinal canal. In the diagram, it has been split obliquely from the external ring along the line of its fibres for about 5 cm laterally and the cut edges reflected upwards and downwards to expose the inguinal canal. This is how it would appear after the first stage of an inguinal hernia repair operation.

Mechanisms of inguinal hernia formation

An indirect and a direct hernia can occur together on the same side—a pantaloon hernia. A hernia may consist merely of peritoneum and associated extraperitoneal fat, but if larger, the sac usually contains omentum or small bowel, or less commonly large bowel or appendix. Occasionally, the contents of the sac are diseased, e.g. large bowel carcinoma, an inflamed appendix (acute appendicitis) or peritoneal tumour metastases. Sometimes a retroperitoneal viscus ‘slides’ down the posterior abdominal wall and herniates directly (occasionally indirectly) into the inguinal canal, dragging its overlying peritoneum with it. Thus, the visceral contents of a sliding hernia lie behind and outside the peritoneal sac (see Fig. 32.5). This most commonly occurs in the left groin involving the descending and sigmoid colon or in larger direct hernias, may involve the bladder.

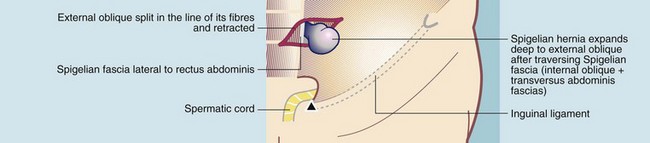

Spigelian hernia

Rarely, herniation occurs through a fascial defect in the linea semilunaris at the lateral border of rectus abdominis. The hernial sac comes to lie interstitially, i.e. between the layers of internal and external oblique or transversus abdominis. This is a Spigelian hernia. It has some clinical characteristics of an inguinal hernia but the bulge lies higher than an inguinal hernia and may be difficult to palpate because it is covered by one or more layers of the abdominal wall (see Fig. 32.6).

Natural history of inguinal hernia

Hernial strangulation

Inguinal hernias that are difficult to reduce or which intermittently cause pain are at particular risk of strangulation. Strangulation occurs if the hernial contents become constricted by the neck of the sac or by twisting. Obstruction of venous return then leads to swelling and later to arterial obstruction. If strangulation is not relieved by manual or operative reduction, infarction follows. A strangulated inguinal hernia first becomes irreducible and then tender and later red. Symptoms and signs of bowel obstruction develop over the next few hours, followed by peritonitis if the bowel perforates (Fig. 32.7). Strangulation is a surgical emergency.

Management of inguinal hernias

Very large ‘wheelbarrow’ hernias are invariably of long standing and are found mainly in elderly men (see Fig. 32.8). They only present when size becomes a handicap, if bowel strangulates within the hernia or if the anatomical distortion interferes with micturition. Bowel adhesions may make operation difficult and postoperative wound infections are common. If the hernia is not strangulated, a bag truss to support the hernia may be an appropriate treatment.

Inguinal herniorrhaphy and herniotomy

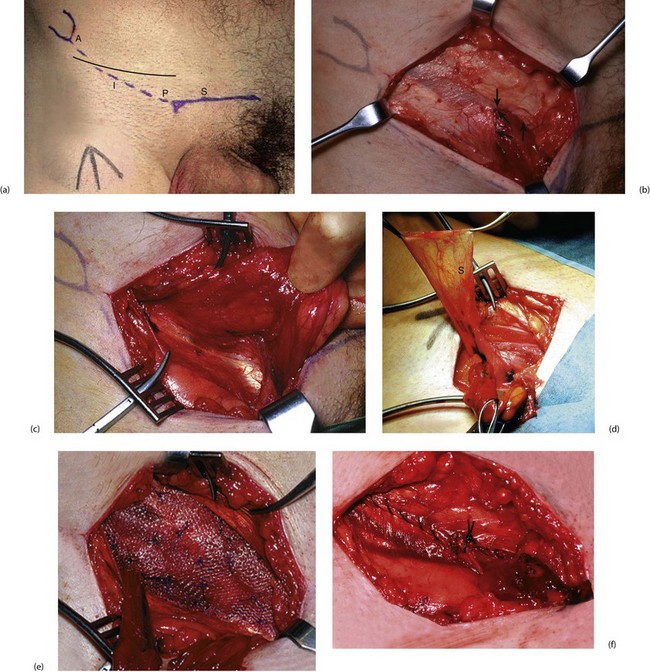

In 1989 Lichtenstein described his mesh implant technique which rapidly became the standard operation. This employs a ‘tension-free’ technique, using a patch of non-absorbable open-weave mesh to repair and reinforce the defect rather than pulling together muscle and fascial layers together under tension. Figure 32.9 shows the principles of the Lichtenstein type of inguinal hernia repair.

Fig. 32.9 Technique of mesh hernia repair

(a) Skin markings demonstrating the upper border of the pubic arch S, the anterior superior iliac spine A, the pubic tubercle P and the inguinal ligament I. Note the side of the planned operation has been marked with an arrow on the thigh to ensure the correct side is operated upon. The line of incision is shown as a solid line.

(b) The dissection down to the external oblique aponeurosis. The external (superficial) ring is arrowed.

(c) External oblique aponeurosis opened, demonstrating the shiny inguinal ligament, which is its inturned lower edge.

(d) The indirect hernia sac S dissected out from the spermatic cord and held upwards before ligation and excision. The inferior epigastric artery and vein lie at the medial border of the deep inguinal ring.

(e) Polypropylene mesh is cut to shape before insertion and sutured in place along the inguinal ligament and, in this case, tacked to the surface of the internal oblique with ‘starry sky’ sutures.

(f) External oblique closed to recreate the inguinal canal before skin closure

The mesh technique has several distinct advantages:

• The technique is easily learned and trainee surgeons can reliably produce good results

• Postoperative pain is substantially less, allowing increased mobility and early return to normal activities such as work and driving

Having a foreign body implanted might be expected to increase the risk of infection but in practice it is exceptionally rare. The mesh used does not have to be expensive—studies are being published of successful hernia repairs in developing countries using sterilised mosquito netting!

Complications of hernia repair: Early complications of herniorrhaphy include scrotal haematoma or wound infection. Most surgeons employ prophylactic antibiotics for mesh repairs but there is little evidence of benefit. Late complications include recurrence (see below), chronic groin pain due to inadvertent trapping of the ilio-inguinal or another nerve in the repair, and testicular atrophy caused by inadvertent damage to the testicular artery, usually with diathermy, or over-tightening of the deep ring.

Recurrence: Inguinal hernias recur in 2–25% of cases over a lifetime. The rate is greatly increased when inadequate attention has been given to operative principles.

The causes of inguinal hernia recurrence include:

• Inappropriate technique—Bassini type repairs have a 25% recurrence rate

• Operator inexperience—Shouldice and laparoscopic repairs have a long learning curve

• Technical failure—failure to recognise and remove an indirect sac at operation; insufficient coverage of the defect; suture or mesh failure

• Missed diagnosis of a concomitant femoral hernia

• Inherently poor musculature, chronic cough, urinary obstruction, constipation or resumption of heavy work too soon after repair

• Underlying physiological problems that impair healing such as poorly controlled diabetes or smoking—smokers have twice the recurrence rates of non-smokers. It is important to screen for problems of this type and address them before hernia surgery

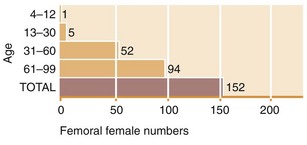

Femoral hernia

A femoral hernia is formed by a protrusion of peritoneum into the potential space of the femoral canal. The sac may contain abdominal viscera (usually small bowel) or omentum. Around 40% of femoral hernias present with strangulation. The incidence is higher in women and increases with age (Figs 32.4 and 32.10). Increased intra-abdominal pressure and other factors related to pregnancy may be important in females since the incidence of femoral hernia is higher in parous than nulliparous women.

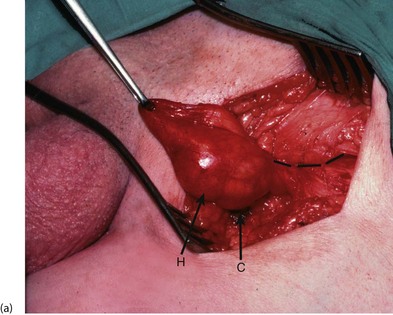

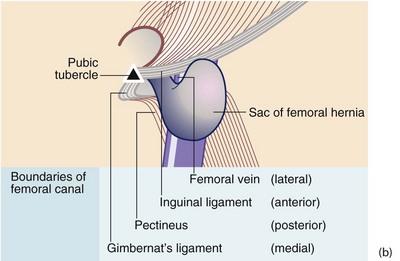

Clinical features of femoral hernia

The anatomy of the femoral canal is shown in Figure 32.1b, page 409. A femoral hernia is usually small, appearing as a lump immediately below the inguinal ligament and just lateral to its medial attachment to the pubic tubercle. Since the femoral canal is narrow, a cough impulse can rarely be detected, and the hernia is usually irreducible. Thus, small femoral hernias may be difficult to distinguish from other lumps arising in the femoral canal such as a lipoma or enlarged Cloquet’s lymph node. However, a hernia is deeply fixed whereas the others tend to be more mobile.

Strangulated femoral hernia

In nearly 30% of strangulated femoral hernias, only a portion of the bowel circumference is trapped in the hernial sac. Although the bowel lumen remains patent and the patient continues to pass flatus, peristalsis is sufficiently disrupted for other signs of obstruction to occur, notably vomiting. This is known as Richter’s hernia (see Fig. 32.11). Resuscitation and urgent operation are required as for completely strangulated hernias.

Management of femoral hernia

Elective repair is performed by first isolating, emptying and excising the peritoneal sac (see Fig. 32.12). The femoral canal is then closed with non-absorbable sutures or a plug placed between pectineus fascia and inguinal ligament. The canal can be exposed by several different methods. The most common are a) the femoral or low approach, b) the Lotheissen or high approach, via the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, and c) the McEvedy or pararectus extraperitoneal approach. The last is virtually a laparotomy and is rarely employed. Occasionally a femoral hernia containing bowel cannot be safely reduced via a local approach, or bowel of doubtful viability escapes back into the abdominal cavity. In either case, a laparotomy incision is required to safely complete the operation.

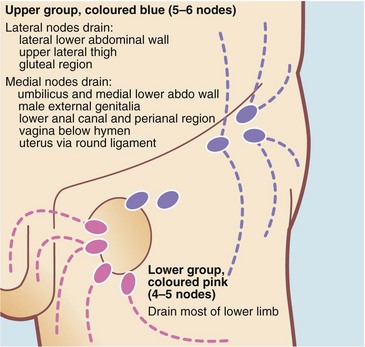

Enlarged inguinal lymph nodes

The lymph nodes of the inguinal region are clustered into the three anatomical groups shown in Figure 32.13. These drain the lower abdominal wall and lower back, perineum (including vulva and vagina), anal canal, penis and scrotal skin and the whole lower limb. The testes are derived from the retroperitoneal area and hence drain to the upper para-aortic nodes within the abdomen rather than inguinal nodes.

Fig. 32.13 Superficial inguinal lymph nodes of the groin

The lower group lie around the termination of the long saphenous vein. Both upper and lower groups drain to the external iliac nodes

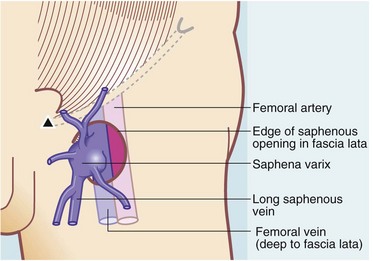

Saphena varix

A saphena varix is a dilatation of the long saphenous vein in the groin, just proximal to its junction with the femoral vein (see Fig. 32.14). The varix is caused by valvular incompetence at this point; there are usually substantial varicose veins elsewhere in the long saphenous system.

The varix can reach the size of a golf ball or even larger. On examination, the swelling is soft and diffuse. The diagnostic feature is that it empties with minimal pressure and refills on release (‘the sign of emptying’). A cough impulse is invariably present and a fluid thrill can be felt if varicosities further down the thigh are tapped lightly. Treatment is high saphenous ligation, as for sapheno-femoral reflux associated with varicose veins (see Ch. 43).

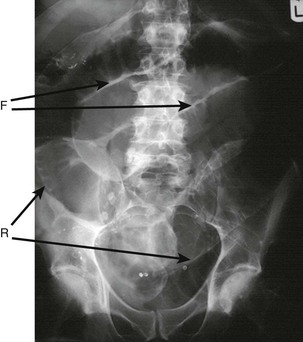

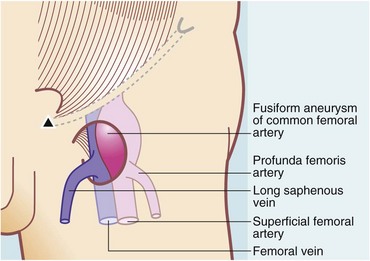

Femoral artery aneurysm

Femoral aneurysms are uncommon as a cause of lumps in the groin. They may occur as part of a generalised aneurysmal disease involving the abdominal aorta, iliac and lower limb arterial system but can also occur in isolation. Diagnosis is made on clinical examination; the lump lies below the midpoint of the inguinal ligament (see Fig. 32.15) and has a characteristic expansile pulsation. Distinguishing an aneurysm from a femoral hernia is clearly vitally important. The management of aneurysms is discussed in Chapter 42.

Ventral hernias

Ventral hernias include epigastric, umbilical and paraumbilical hernias. Ventral incisional hernias occurring through previous surgical or traumatic wounds are considered in Chapter 12.

Epigastric hernias (see Fig. 32.16)

These are midline herniations through defects in the linea alba, anywhere between xiphoid process and umbilicus. They are four times more common in males and are often tiny, with a defect less than 0.5 cm. Most are symptomless and the presence of a lump and sometimes episodic sharp pain on exertion are the usual presenting complaints. Treatment is by direct suture repair if the hernial defect is smaller than 1 cm. Larger hernias may require a tension-free mesh repair.

Umbilical and paraumbilical hernias

Umbilical hernias in children are discussed in Chapter 51. Paraumbilical hernias are acquired rather than congenital. They occur in all age groups but are five times more common in females. The abdominal wall defect is in the linea alba, generally above or below the umbilical cicatrix. The swelling lies adjacent to the umbilicus, with the umbilicus itself pushed to the side to produce the characteristic ‘smile’ of a paraumbilical hernia.