113 Hernias

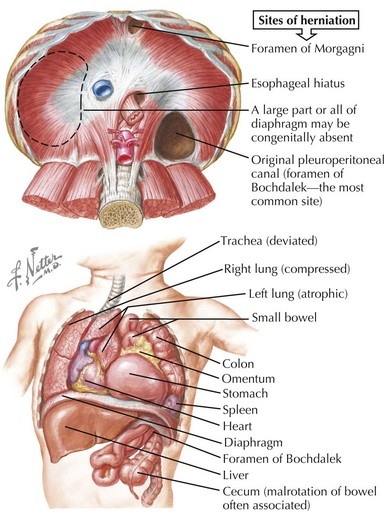

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) and hiatal hernia are the two most common internal hernia types among children. CDH is a neonatal surgical emergency that presents with a scaphoid abdomen, cyanosis, and respiratory distress within minutes of birth as a result of the herniation of abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity (Figure 113-1 see Chapter 102). Hiatal hernias, in which intraabdominal portions of the esophagus, the stomach, or both pass into the thorax, are less common in children than adults but remain an important consideration in certain clinical circumstances. Other internal hernias, including paraduodenal and mesenteric hernias, occur within the abdominal cavity. These are largely the result of congenital abnormalities and in rare circumstances become clinically relevant in childhood.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

External Hernias

Inguinal Hernia

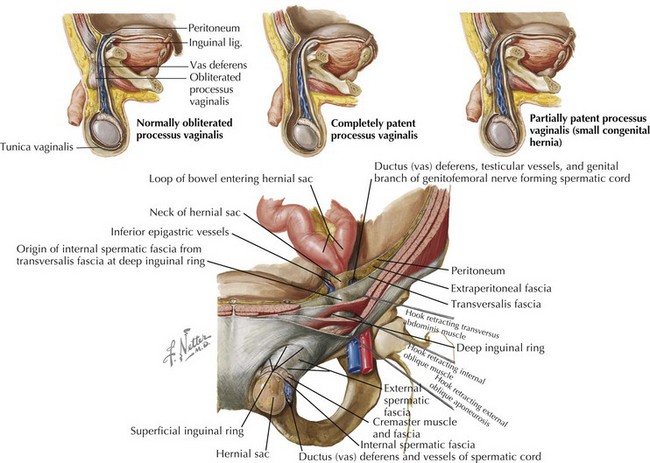

Indirect inguinal hernias are congenital in origin, arising from incomplete embryogenesis. In boys, the testes are initially in a retroperitoneal position. A portion of peritoneum called the processus vaginalis attaches to the testes and precedes the testicular descent through the internal inguinal ring into the scrotal sac. The testes are located at the internal inguinal ring by 28 weeks of gestation and reach their final destination by 36 weeks with the left side completing its descent slightly earlier than the right. The processus vaginalis creates a patent conduit between the abdomen and the scrotum via the inguinal canal and typically obliterates between 36 and 40 weeks of gestation or in the postnatal period. If the processus vaginalis remains patent, abdominal contents may escape through the internal inguinal ring into the inguinal canal and the scrotum (Figure 113-2).

Abdominal Wall Hernias

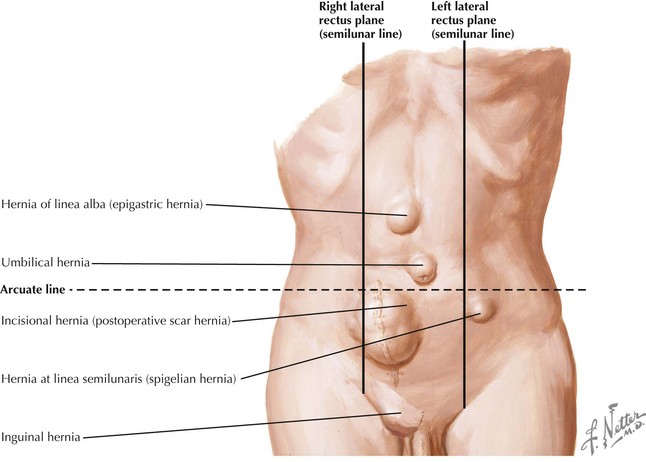

Epigastric hernias occur above the umbilicus through a defect in the linea alba and most commonly contain preperitoneal fat. Such a defect develops when there is failure of complete approximation of the midline during the final stages of abdominal wall formation. Incisional hernias, resulting from incomplete healing of a surgical incision, can occur anywhere on the abdomen. Any process that increases intraabdominal pressure, obesity, and postoperative wound infections are major risk factors for incisional hernias. Spigelian hernias, reported rarely in children, occur in an area of natural weakness at the lateral edge of the rectus abdominus muscle and below the arcuate line where only transversalis fascia lies posterior to the rectus abdominus (Figure 113-3).

Internal Hernias

Hiatal Hernia

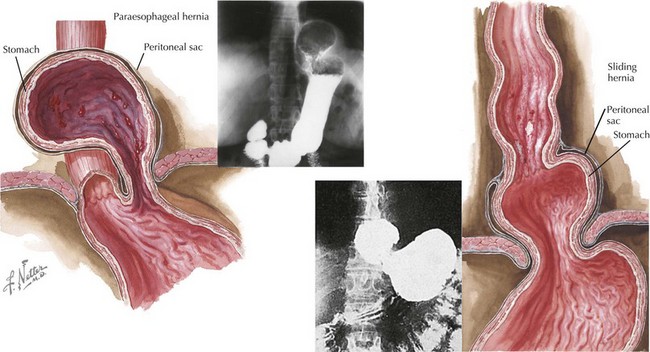

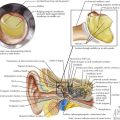

The intraabdominal esophagus and the stomach are secured in place by numerous fascial and ligamentous elements. At its entry into the abdomen, the esophagus is supported by fibroelastic tissue called the phrenoesophageal membrane. This membrane, as well as many other supporting structures, can be structurally deficient at birth or gradually weaken with time and stress, causing laxity of the support and widening of the muscular hiatus. During inspiration, the transdiaphragmatic pressure differential causes the esophagus and stomach to be pulled upward. Depending on the areas of weakness, the gastroesophageal junction may slide into the posterior mediastinum or a portion of the stomach may pass through the hiatus alongside the esophagus with the lower esophageal sphincter maintained in its correct anatomic position (Figure 113-4).

Clinical Presentation

Inguinal hernias can present at birth or any time during childhood. The history may include a description of the bulge extending to the scrotum or labia majora. The differential diagnosis of an inguinal-scrotal or labial swelling also includes incarcerated inguinal hernia, hydrocele, torsion of an undescended testis, and inguinal lymphadenitis. History and a detailed gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary examination should differentiate between these entities (Table 113-1). Observing the mass increasing in size during a period of increased intraabdominal pressure and decreasing in size during relaxation or gentle taxis strongly suggests the diagnosis of inguinal hernia. A firm, smooth mass is often palpable at the external inguinal ring. The smooth sensation of the herniated sac rolling over itself when palpated at the pubic tubercle is known as the “silk glove sign” and supports the diagnosis of hernia. Transillumination is not specific for hydroceles and should be used with caution as a tool to differentiate from hernias. Hernias may transilluminate as well, especially in the incarcerated state with excess bowel wall edema. Close inspection of the contralateral inguinal region is important because 10% of patients have bilateral inguinal hernias. Determining if the hernia is indirect or direct is frequently difficult on examination and is often not confirmed until surgery. A femoral hernia is clinically seen as a swelling in the femoral canal inferior to the inguinal ligament but may also be confused for an inguinal hernia.

Table 113-1 Differential Diagnosis of Inguinal-Scrotal or Labial Swelling

| Clinical Condition | Distinguishing Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Reducible inguinal hernia |

The cardinal symptoms of a sliding hiatal hernia are regurgitation and heartburn, which are manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux (GER; see Chapter 107). When a hiatal hernia is the underlying cause, GER may be associated with complications such as pulmonary infections secondary to aspiration, vomiting, and failure to thrive. Dysphagia may also be described but tends to be a later finding. Paraesophageal hiatal hernias can present in similar fashion to a sliding hernia; however, dysphagia, early satiety, and chest pain tend to be more prominent with paraesophageal hernias. Sliding and paraesophageal hiatal hernias should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis for any of these presenting symptoms. The physical examination may provide insight to the presence of GER but is not helpful in making the diagnosis of either type of hiatal hernia.

Evaluation and Management

Brandt ML. Pediatric hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88(1):27-43.

Curci JA, Melman LM, Thompson RW, et al. Elastic fiber depletion in the supporting ligaments of the gastroesophageal junction: a structural basis for the development of hiatal hernia. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(2):191-196.

Snyder C. Current management of umbilical abnormalities and related anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16:41-49.

Vandenplas Y, Hassall E. Mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35(2):119-136.