38 Hernias

• Smaller defects in the abdominal wall are more likely to be manifested as incarcerated or strangulated hernias.

• Reduction of a hernia should not be attempted if strangulation is suspected.

• Hernias with signs or symptoms suggestive of bowel obstruction or ischemia are true surgical emergencies and require immediate consultation for operative repair.

• Manual reduction can be aided by placement of the patient in a supine or Trendelenburg position, application of ice to the hernia site before reduction, and administration of analgesics or anxiolytics, or both.

• Postoperative complications of herniorrhaphy include wound infection, seroma, hematoma, ileus, small bowel obstruction, recurrence of the hernia, erosion of preperitoneal mesh into intraabdominal organs, fistula formation, genitourinary trauma, and chronic pain secondary to nerve injury.

Epidemiology

Herniorrhaphy (also known as hernioplasty, or surgical repair of a hernia) is a common procedure in the United States. Approximately 800,000 inguinal hernia repairs were performed in the United States in 2003; mesh was used in 90% of the cases.1

Nomenclature

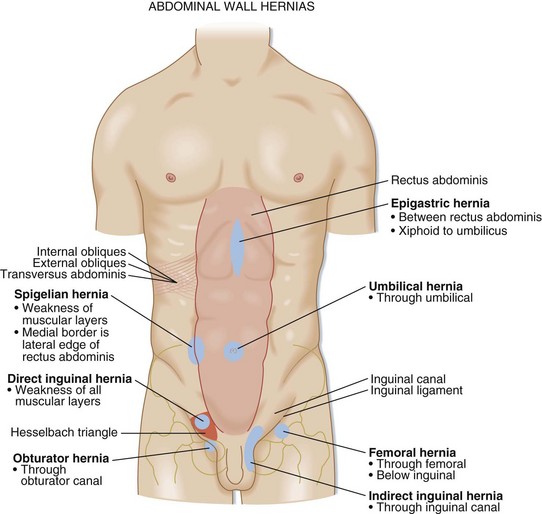

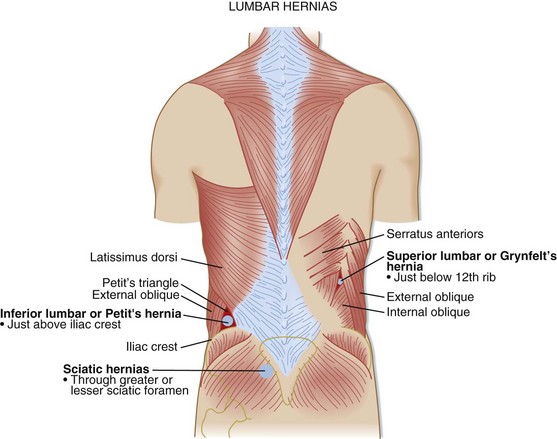

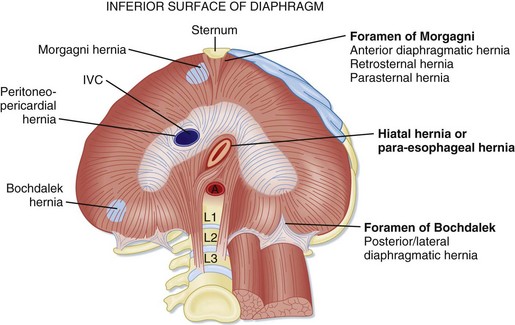

Table 38.1 and Box 38.1 summarize the nomenclature of hernias, and Figures 38.1 to 38.13 illustrate some of the hernia types.

| Groin Hernias | |

| Inguinal hernia (Fig. 38.1) | Physical examination cannot accurately distinguish between indirect and direct inguinal hernias |

| Indirect | Occurs through the inguinal canal |

| Inguinal canal contents include the ilioinguinal nerve, genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, spermatic cord in men (vas deferens, testicular artery, and vein), and round ligament in women | |

| Direct | 65% of inguinal hernias are indirect |

| Weakness of the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis and transversalis fascia in the Hesselbach triangle (the medial border of which is the lateral aspect of the rectus abdominis, the superior border is the epigastric artery, and the inferior border is the inguinal ligament) | |

| Femoral hernia | Occurs through the femoral canal, inferior to the inguinal ligament, medial to the femoral vein |

| More common in elderly, parous women | |

| Sportsman’s hernia | Syndrome of persistent groin pain in athletes; probably caused by recurrent or persistent groin strain, osteitis pubis, or a nonpalpable hernia |

| More common in kicking sports | |

| Abdominal Wall Hernias | |

| Anterior (Fig. 38.2) | |

| Epigastric hernia | Occurs through the linea alba, the midline between the xiphoid line and umbilicus |

| Umbilical hernia | Caused by an abnormally large or weak umbilical ring |

| Umbilical hernia usually closes spontaneously in infancy but does not heal in adulthood | |

| Rarely incarcerates in children | |

| Worsened by pregnancy, obesity, or cirrhosis with ascites | |

| Spigelian hernia (Figs. 38.3 and 38.4) | Lateral ventral hernia through the spigelian zone: transversalis fascia between the lateral margin of the rectus abdominis muscle, medial margins of the external and internal obliques, and the transversus abdominis muscles |

| Accounts for 1-2% of all hernias | |

| Ventral or incisional hernia (Fig. 38.5) | Trocar sites: |

Immediate management: cover the abdominal contents with warm moist saline-soaked gauze, insert a nasogastric tube, administer intravenous fluids and antibiotics, obtain surgical consultation

Types:

Box 38.1 Eponyms Associated with Hernias

Richter hernia (partial enterocele): Herniation of only the anterior surface of the intestinal wall through the hernia defect; accounts for 10% of strangulated hernias

Amyand hernia: Acute appendicitis in the sac of an inguinal hernia

Garengeot hernia: Acute appendicitis in the sac of a femoral hernia

Littre hernia: Strangulated Meckel diverticulum in a hernia sac

Maydl hernia: Internal hernia with double-loop strangulation

Chilaiditi syndrome: Symptomatic interposition of the intraabdominal contents between the liver and diaphragm; can become incarcerated

Canal of Nuck: The portion of the processus vaginalis that accompanies the round ligament through the inguinal canal in women; may contain hernia contents or, rarely, hydrocele in women

Romberg-Howship sign: Lancinating pain along the inner side of the thigh to the knee or down the leg to the foot caused by compression of the obturator nerve in cases of incarcerated obturator hernia

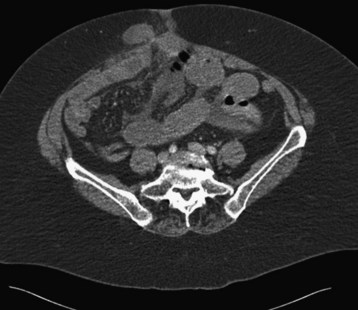

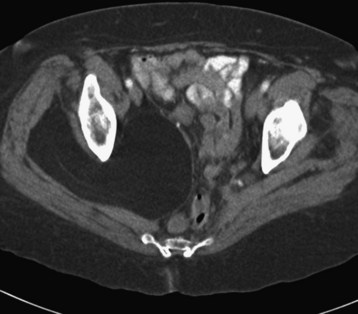

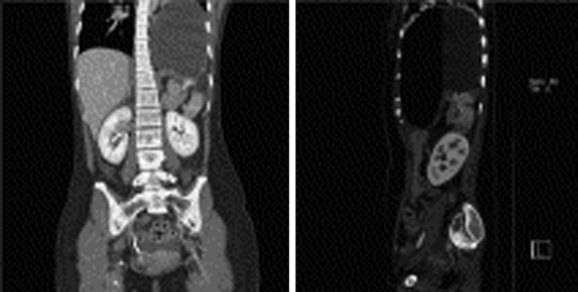

Fig. 38.4 Computed tomography scan of a spigelian hernia in an adult woman with right lower quadrant pain.

(From Mull AC, Hurtado TR. Right lower quadrant pain in an adult woman. Am J Emerg Med 2011;29:132.e1-2.)

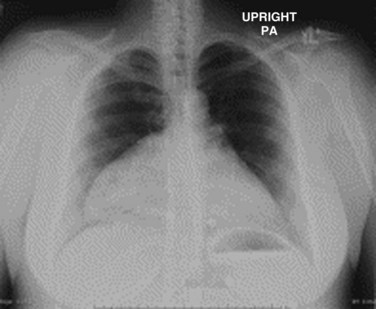

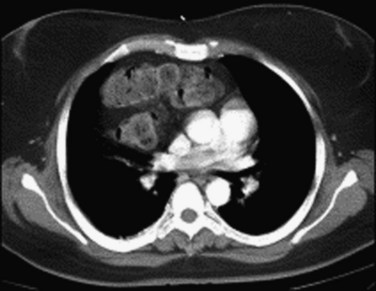

Fig. 38.8 Morgagni-type diaphragmatic hernia manifested as an abnormal cardiac silhouette.

(From Daneshvar S, Shriki J, Sohn H, et al. Morgagni-type diaphragmatic hernia presenting as an abnormal cardiac silhouette. Am J Med 2010;123:e11-2.)

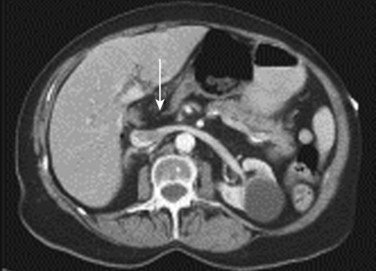

Fig. 38.9 Morgagni-type diaphragmatic hernia manifested as an abnormal cardiac silhouette (arrow).

(From Daneshvar S, Shriki J, Sohn H, et al. Morgagni-type diaphragmatic hernia presenting as an abnormal cardiac silhouette. Am J Med 2010;123:e11-2.)

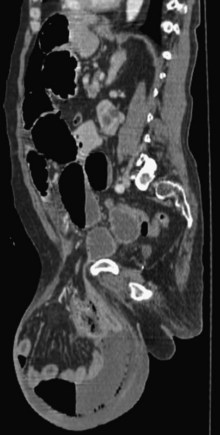

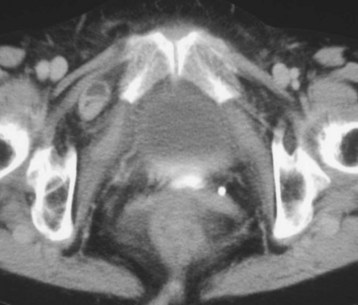

Fig. 38.10 Computed tomographic scan of a diaphragmatic hernia.

(From Yang YM, Yang HB, Park JS, et al. Spontaneous diaphragmatic rupture complicated with perforation of the stomach during Pilates. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:259.e1-3.)

Pathophysiology

In comparison with controls, patients in whom incisional or recurrent hernias develop may exhibit abnormal synthesis of type I and type III collagen.2 A higher incidence of incisional hernia formation is seen in patients with wound infection, obesity, and multiple comorbid conditions. The use of synthetic mesh and “tension-free” repair techniques has reduced rates of hernia recurrence.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The incidence of postoperative internal hernias is rising because of the increase in bariatric operations in the United States, particularly Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.3 Postoperative complications of hernia repair include wound infection, seroma or hematoma, ileus or small bowel obstruction, recurrence of the hernia, and in rare cases, erosion of preperitoneal mesh into intraabdominal organs with associated fistula formation.4 Complications of inguinal hernia repair are chronic pain as a result of nerve disruption or entrapment and, rarely, testicular ischemia.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis of abdominal wall hernias includes other masses involving the abdominal wall, such as lipomas and rectus sheath hematomas. Abdominal wall or intraabdominal hernias should be considered a potential cause in patients with signs and symptoms of small bowel obstruction. In patients who have previously undergone abdominal surgery, either open or laparoscopic, careful examination of the incisions,5 trocar sites,6 and parastomal areas7 should be performed to detect masses or abdominal wall defects. To facilitate detection of the hernia, the examiner should hold the tips of the fingers over the incision while the patient coughs or strains.8

Inguinal hernias should be considered in the evaluation of patients with scrotal pain or swelling. Detection of inguinal hernias is improved by examination of the patient in a standing position and insertion of the examiner’s finger into the inguinal canal through the loose skin of the scrotum. This technique allows direct palpation of the inguinal ring. Having the patient cough or strain allows the examiner to palpate the hernia bulging against the examining finger. Other causes of scrotal pain, masses, or swelling are testicular torsion, tumor, orchitis, epididymitis, lipoma, hydrocele, and varicocele.9

Ultrasonography is the imaging modality of choice in the evaluation of scrotal swelling or masses because it allows differentiation of the testicles, spermatic cord, hydrocele, or varicocele separately from the hernia contents. This modality can assist in the diagnosis of abdominal wall hernias through identification of bowel loops within the hernia sac. Color flow Doppler imaging can detect the presence or absence of blood flow in some cases, thereby aiding in the diagnosis of strangulation.10

Pediatric Considerations

Congenital diaphragmatic hernias occur in 1 in 2500 births. The mortality rate is high because of pulmonary hypoplasia and the development of pulmonary hypertension. Ultrasonography allows prenatal diagnosis and identification of infants with the potential for a poor prognosis. The prognosis worsens when the liver is located intrathoracically and total lung volume is less than total head volume. In utero repair of diaphragmatic hernias has been performed, although better outcomes than those with conventional treatment have not been observed.11

Percutaneous placement of a fetal endoluminal tracheal occlusion balloon may improve survival by preventing egress of the pulmonary fluid needed to stimulate lung growth.12 This treatment is still controversial because of a higher incidence of preterm labor. Stabilization of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia consists of intravenous fluid resuscitation, insertion of a nasogastric tube, intubation with gentle ventilation or permissive hypercapnia (to avoid barotrauma), and surgical consultation. The use of nitric oxide and surfactant has not been demonstrated to improve outcomes in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernias.

Treatment

Hospital

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Analgesia, fluid resuscitation, attempts at manual reduction of the hernia, and procedural sedation should be used as necessary.

Complications of persistent hernia incarceration include small bowel obstruction, bowel ischemia, or necrosis of the hernia contents.

Surgical consultation should be obtained for possible operative intervention in cases of persistent incarceration, small bowel obstruction, bowel ischemia or necrosis.

The current surgical trend is toward laparoscopic repair of most hernias.13 Laparoscopic repair of incisional hernias tends to decrease perioperative pain and recovery time and has complication and recurrence rates similar to those with open repair.14 Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair has a slightly higher incidence of bladder and vascular injury than open repair does.15

Postoperative complications of hernia repair include bowel injury, hemorrhage, wound infection, and recurrence. The use of prosthetic mesh has decreased hernia recurrence, although mesh is problematic when wound infection occurs. Late complications of the use of prosthetic mesh for hernia repair consist of fibrosis and erosion into adjacent structures, including bowel and bladder, and occasionally fistula formation.16

Other complications of inguinal hernia repair are entrapment of the genitofemoral or ilioinguinal nerves, persistent pain syndromes, and in male patients, injury to the vas deferens and testicles with resultant alterations in fertility.17 Repair of abdominal wall hernias can injure cutaneous nerves and give rise to persistent abdominal wall pain syndromes.18

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Emergency repair of incarcerated or strangulated hernias is associated with higher morbidity and mortality than is the case with elective repair, especially in elderly patients or those with multiple medical comorbid conditions.19 Complications include a higher incidence of bowel ischemia and necrosis, wound infection and dehiscence, intraabdominal compartment syndrome, sepsis and respiratory compromise, and hernia recurrence.20

Patients with easily reducible hernias may be discharged for surgical follow-up and elective hernia repair. Repair is generally recommended for symptomatic hernias in otherwise healthy patients. Patients who have multiple medical problems and for whom surgery poses a high risk may not be suitable candidates for elective hernia repair, especially when the fascial defect is large and less likely to become incarcerated. The decision about the timing of hernia repair should be made by the patient in conjunction with the primary care physician and the surgeon. Elective repair of symptomatic hernias in elderly patients should be considered.21

![]() Documentation

Documentation

INCA Trialists Collaboration. Operation compared with watchful waiting in elderly male inguinal hernia patients: a review and data analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:251–259. e1-4

Maish MS. The diaphragm. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:955–968.

Monkhouse SJ, Morgan JD, Norton SA. Complications of bariatric surgery: presentation and emergency management—a review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:280–286.

Montgomery JS, Bloom DA. The diagnosis and management of scrotal masses. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:235–244.

1 Carbajo MA, Martin del Olmo JC, Blanco JI, et al. Laparoscopic treatment versus open surgery in the solution of major incisional and abdominal wall hernias with mesh. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:250–252.

2 Si Z, Bhardwaj R, Rosch R, et al. Impaired balance of type I and type III procollagen mRNA in cultured fibroblasts of patients with incisional hernia. Surgery. 2002;131:324–331.

3 Garza E, Jr., Kuhn J, Arnold D, et al. Internal hernias after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y bypass. Am J Surg. 2004;188:796–800.

4 Eckhauser A, Torquati A, Youssef Y, et al. Internal hernia: postoperative complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Am Surg. 2006;72:581–584. discussion 584-585

5 Cassar K, Munro A. Surgical treatment of incisional hernia. Br J Surg. 2002;89:534–545.

6 Tonouchi H, Ohmori Y, Kobayashi M, et al. Trocar site hernia. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1248–1256.

7 Carne PW, Robertson GM, Frizelle FA. Parastomal hernia. Br J Surg. 2003;90:784–793.

8 Yahchouchy-Chouillard E, Aura T, Picone O, et al. Incisional hernias. I: related risk factors. Dig Surg. 2003;20:3–9.

9 Rubenstein RA, Dogra VS, Seftel AD, et al. Benign intrascrotal lesions. J Urol. 2004;171:1765–1772.

10 Toms AP, Dixon AK, Murphy JMP, et al. Illustrated review of new imaging techniques in the diagnosis of abdominal wall hernias. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1243–1249.

11 Moyer V, Moya F, Tibboel R, et al. Late versus early surgical correction for congenital diaphragmatic hernia in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2002. CD001695

12 Harrison MR, Keller RL, Hawgood SB, et al. A randomized trial of fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion for severe fetal congenital diaphragmatic hernia. N Engl J Med. 2003;13:1916–1924.

13 Bax T, Sheppard BC, Crass RA. Surgical options in the management of groin hernias. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:893–906.

14 Zanghi A, Di Vita M, Lomenzo E, et al. Laparoscopic repair versus open surgery for incisional hernias: a comparison study. Ann Ital Chir. 2000;71:663–667.

15 McCormack K, Scott NW, Go PM, et al. EU Trialists Collaboration: laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2003. CD001785

16 Scott NW, McCormack K, Graham P, et al. Open mesh versus non-mesh repair of femoral and inguinal hernia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2002. CD002197

17 Ridgeway PR, Shah J, Darzi AW. Male genital tract injuries after contemporary inguinal hernia repair. Br J Urol. 2002;90:272–276.

18 Poobalan AS, Bruce JM, Smith WC, et al. A review of chronic pain after inguinal herniorrhaphy. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:48–54.

19 Kulah B, Duzgan AP, Moran M, et al. Emergency hernia repairs in elderly patients. Am J Surg. 2001;182:455–459.

20 Alvarez Perez JA, Baldonedo RF, Bear IG, et al. Emergency hernia repairs in elderly patients. Int Surg. 2003;88:231–237.

21 Henrickson NA, Yadele DH, Sorensen LT, et al. Connective tissue alteration in abdominal wall hernia. Br J Surg. 2011;98:210–219.