115 Hepatobiliary Disease

Normal Anatomy and Physiology

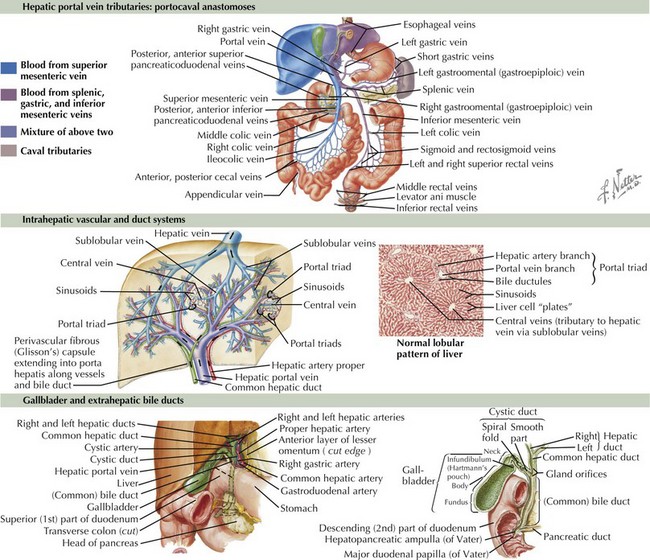

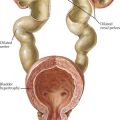

The liver arises from endoderm between the third and fourth weeks of gestation. The liver is important in the production of bile, synthesis of coagulation factors, metabolism of proteins and glucose, and biotransformation of drugs and toxins. It consists of four lobes: right, left, caudate, and quadrate. An understanding of the liver’s blood supply is useful when considering the consequences of portal hypertension (Figure 115-1). The portal vein and hepatic artery bring blood to the liver. The portal vein, which receives its supply from the splenic vein and mesenteric veins, carries about 75% of the liver’s blood supply. The hepatic artery receives its blood supply from the celiac axis. Blood exits the liver through the hepatic vein, which empties into the inferior vena cava. Bile exits the liver by way of the intrahepatic bile ducts that lead to the right and left hepatic ducts, which merge to form the common hepatic duct. The common hepatic duct merges with the cystic duct from the gallbladder to form the common bile duct, which allows drainage of bile into the duodenum.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Two common manifestations of hepatobiliary disease are elevations in liver transaminases and jaundice. Elevations of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) arise from hepatocyte injury. Elevations of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) result from impaired bile flow. Jaundice results from an elevation in conjugated or unconjugated bilirubin. Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia occurs in about 60% of full-term infants and is most commonly physiologic jaundice partly caused by the immaturity of the bilirubin conjugation process (see Chapter 100). Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia may also arise from hemolytic anemia (leading to overproduction of bilirubin) or abnormal bilirubin conjugation. Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is always considered pathologic (see below).

Clinical Presentation

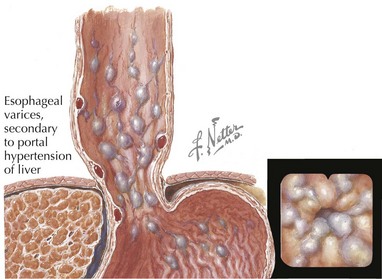

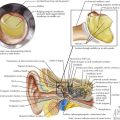

Hepatobiliary diseases can present as acute fulminant liver failure or can be quiescent with an insidious onset. A thorough history can be very helpful in narrowing down the differential diagnosis of liver disease. Knowledge of the time of onset of all symptoms, including jaundice, is helpful. Breast milk jaundice develops after the seventh day of life, in contrast to breastfeeding jaundice, which occurs in the first week of life. Both of these entities present with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Infants who have conjugated hyperbilirubinemia from the first day of life most likely have a pathologic process. The medical provider should ask about medications taken by the child or the mother (in the case of a breastfed infant). Dark urine, abdominal enlargement, easy bruising, epistaxis, and pruritus may be reported in the history of a patient with liver disease. A patient with portal hypertension may present with hematemesis from an esophageal variceal bleed (Figure 115-2). It is important to ask about potential exposures to viral hepatitis and recent travel. Family history is important to address the possibility of hepatitis B or C transmission.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis is vast and can be divided by age (Table 115-1). The provider should always focus on quickly diagnosing diseases requiring urgent treatment. In the Pediatric Acute Liver Failure Registry, the most common diagnosis is indeterminate (49%); additionally, acetaminophen intoxication accounts for 14%, metabolic disease accounts for 10%, autoimmune hepatitis and infectious causes each account for 6%, and non-acetaminophen drug-induced liver disease accounts for 5% of cases. Data from the United Network for Organ Sharing show that the most common diagnoses in children who received a liver transplant from 1995 to 1999 were biliary atresia (BA; 35.6%), viral hepatitis (13%), metabolic liver disease (11.4%), intrahepatic cholestasis (7.9%), TPN (5.4%), and idiopathic cirrhosis (4.8%).

Table 115-1 Differential Diagnosis of Hepatobiliary Disease in Children*

| All Ages | Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Viral infection: EBV; CMV; hepatitis A, B, and C; herpes simplex virus, echovirus, enterovirus, rubella, parvovirus, adenovirus, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, HIV, varicella | 12.0 |

| Bacterial infection: sepsis, UTI, tuberculosis, Listeria, treponema pallidum | |

| Extrahepatic obstruction: choledochal cyst, bile duct stricture or tumor, cholelithiasis) | |

| Drugs (valproate, isoniazid, acetaminophen) | 1.1 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 5.4 |

| ECMO | |

| CF | 1.9 |

| Ischemia secondary to congenital heart disease, asphyxia, cardiac surgery | |

| Metabolic: AAT deficiency, fatty acid oxidation defect, urea cycle disorders | 11.4 |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis: PFIC 1, 2, and 3; Alagille’s syndrome | 7.9 |

| Idiopathic | 4.8 |

| Neonates and Infants | |

| See All Ages | |

| Biliary atresia | 35.6 |

| Endocrine (hypothyroidism, panhypopituitarism) | |

| Metabolic: galactosemia, glycogen storage disease, hereditary fructose intolerance, tyrosinemia | |

| Disorders of lipid metabolism: Wolman’s disease, Niemann-Pick disease, Gaucher’s disease | |

| Bile acid synthesis defects | |

| Idiopathic neonatal hepatitis | |

| Mitochondrial disorders | |

| Neonatal lupus erythematosus | |

| Neonatal hemachromatosis | |

| Congenital hepatic fibrosis and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease | 2.1 |

| Peroxisomal disorders (Zellweger’s syndrome) | |

| Young Children | |

| See All Ages | |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 2.6 |

| Malignancy | 3.5 |

| Older Children and Adolescents | |

| See All Ages and Young Children | |

| Acetaminophen overdose | |

| NAFLD | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis (≈68% have IBD) | 1.8 |

| Wilson’s disease | 1.1 |

| Fatty liver disease of pregnancy |

AAT, α-1-antitrypsin; CF, cystic fibrosis; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NAFLD, Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NANB, non-A, non-B; PFIC, progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis; UTI, urinary tract infection.

* Percentages of total cases of liver transplant recipients (UNOS 1995–1999) identified as having the listed diagnosis are shown.

Neonates and Infants

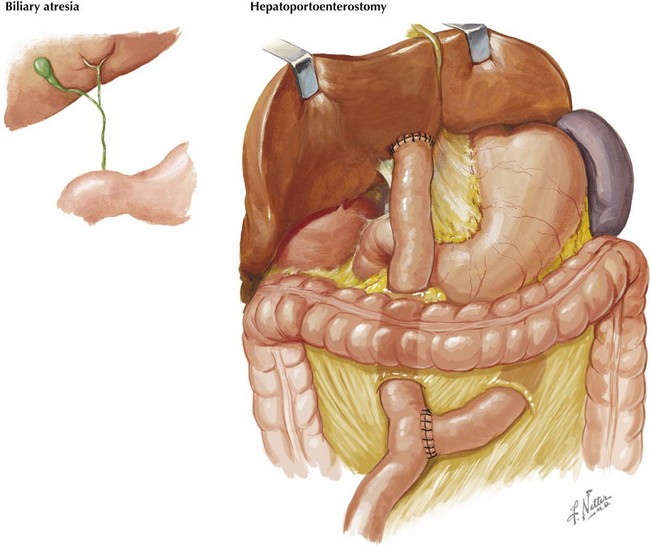

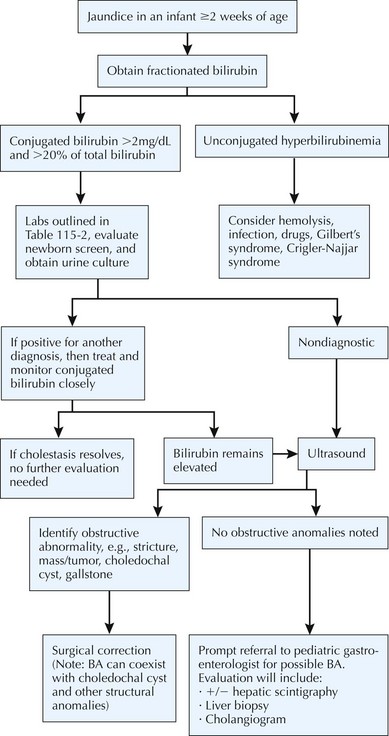

BA is specific to neonates because it occurs only in the first several weeks of life. Although it is rare, early diagnosis and treatment are imperative to a good outcome. BA is a progressive, idiopathic, necroinflammatory process involving the biliary tree, which leads to obstruction of bile flow (Figure 115-3). At presentation, most infants are thriving and appear quite well despite being jaundiced. BA is treated surgically with hepatoportoenterostomy (see Figure 115-3). Despite this intervention, BA is still the most common reason for liver transplantation in children. To facilitate early detection of BA, it is very important that the evaluation of jaundiced infants beyond the first few days of life includes a fractionated bilirubin level. Any infant with a conjugated bilirubin greater than 2 mg/dL or more than 20% of the total bilirubin level requires a thorough evaluation (Figure 115-4).

Older Children and Adolescents

Use of various prescribed (isoniazid, valproate, other antiseizure medications) or recreational (cocaine, “Ecstasy”) drugs can lead to acute liver failure. Intentional or nonintentional overdose of acetaminophen is a common cause for acute liver failure in older children and adolescents. Acetaminophen overdose accounts for 21% of all patients 3 years and older who present with acute liver failure (see Chapter 9).

Evaluation

Although the laboratory evaluation of a child with suspected hepatobiliary disease can be quite extensive, there are studies that should be performed at the beginning of every evaluation (Table 115-2). A complete cell count may reveal a low platelet count or a low white blood cell (WBC) count, which may be seen with cirrhosis and hypersplenism. An elevated WBC count may indicate an infectious process. AST and ALT levels are usually elevated in liver disease, but in liver failure, the transaminases may decrease because of near-total hepatocyte loss. In this case, the synthetic function of liver is compromised, and the prothrombin time is prolonged. High GGT and ALP levels are seen with cholestatic processes, with the rare exception of some types of bile acid synthetic disorder or progressive familiar intrahepatic cholestasis. AAT deficiency can present at any age and can have a variable presentation, including neonatal cholestasis, asymptomatic hepatomegaly, or advanced liver disease. A low AAT level can be suggestive of AAT deficiency, but protease inhibitor (PI) typing is necessary to make the diagnosis of AAT deficiency. Abdominal ultrasonography is a noninvasive way to exclude anatomic abnormalities, such a choledochal cyst, choledocholithiasis, tumors, or vascular anomalies. Ultrasound is also useful in assessing hepatosplenomegaly, especially in patients with ascites in whom the physical examination may be difficult. Lack of visualization of the gallbladder may occur in diseases that involve the biliary system, such as BA and Alagille’s syndrome.

| Test | Significance |

|---|---|

| AST, ALT, LDH | Elevation results from injury of hepatocytes |

| GGT, ALP | Elevation results from impaired bile flow |

| Fractionated bilirubin | Elevation of conjugated bilirubin in cholestasis |

| Complete metabolic panel | Albumin is low in compromised liver synthetic function |

| PT and PTT | PT prolongation may reflect abnormal synthetic function or vitamin K deficiency |

| CBC | Thrombocytopenia and lymphopenia in advanced liver disease with hypersplenism |

| Ammonia | Elevated in advanced liver disease; important to assess this in liver patients with altered level of consciousness |

| Sweat test | Many state newborn screens include test for the more common CF mutations only; therefore, sweat test should be obtained if CF is suspected |

| AAT serum level and PI type | Serum level is low in AAT deficiency; PI type is needed to make the definitive diagnosis |

AAT, α-1-antitrypsin; ALP, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CBC, complete cell count; CF, cystic fibrosis; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PI, protease inhibitor; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

Neonates and Infants

As mentioned earlier, the evaluation of neonates with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia should focus on exclusion of disorders requiring immediate treatment, such as BA (see Figure 115-4). The evaluation for BA should take no more than 4 to 5 days. The newborn screen should be reviewed because it may help to exclude thyroid abnormalities, galactosemia, CF, and rare metabolic disorders. A catheterized urine culture should be obtained because UTIs can lead to cholestasis. In addition to a urine culture, a number of other urine tests should be obtained in the evaluation of a neonate with cholestasis, including urine succinylacetone (present in tyrosinemia), urine organic acids (abnormal in organic acidemias, peroxisomal diseases), and urine bile acids (bile acid synthetic defects). An ophthalmologic examination by a pediatric ophthalmologist may reveal posterior embryotoxon, which is seen in Alagille’s syndrome. A sweat test should also be obtained if CF is not part of the state’s newborn screen.

Management

Many liver diseases are managed supportively and ultimately require liver transplantation. However, a number of hepatobiliary diseases may respond to specific therapies (Table 115-3).

Table 115-3 Examples of Specific Therapies for Liver Diseases

| Disease | Therapy |

|---|---|

| Chronic hepatitis B | Lamivudine, IFN-α |

| Chronic hepatitis C | Ribavirin, IFN-α |

| Galactosemia | Elimination of dietary galactose |

| Acetaminophen overdose | N-acetylcysteine |

| Wilson’s disease | Chelation |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Corticosteroids, azathioprine, 6-MP |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | Weight loss and control |

IFN, interferon; MP, mercaptopurine.

Some of the complications associated with cirrhosis or portal hypertension are gastrointestinal bleeding, ascites, and hypersplenism. An esophageal variceal bleed can occur secondary to portal hypertension (see Figure 115-2). After they are hemodynamically stable, these patients usually undergo endoscopic intervention, such as sclerotherapy or banding. Diuretics are commonly used in the management of ascites. Abdominal paracentesis may be diagnostic (if spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is suspected) and therapeutic. β-Blockers and portosystemic shunts are sometimes used in pediatric patients with portal hypertension.

Arya G, Balistreri WF. Pediatric liver disease in the United States: Epidemiology and impact. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:521-525.

Haber BA, Russo P. Biliary atresia. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:891-911.

Squires RH, Shneider BL, Bucuvalas J, et al. Acute liver failure in children: the first 348 patients in the Pediatric Acute Liver Failure Study Group. J Pediatr. 2005;148:652-658.

Suchy FJ, Sokol RJ, Balistreri WF. Liver Disease in Children, ed 3. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007.