Hemorrhoids and Hemorrhoidectomy

Anatomy of Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids are specialized, nonpathologic, vascular cushions found within the anal canal. They are typically organized into three anatomically distinct cushions located in the left lateral, right anterolateral, and right posterolateral anal canal (Fig. 26-1, A). Hemorrhoids are found in the submucosal layer and are considered sinusoids because they typically have no muscular wall. They are suspended in the anal canal by the muscle of Treitz, which is a submucosal extension of the conjoined longitudinal ligament.

Hemorrhoids are classified as internal or external. Internal hemorrhoids are located proximal to the dentate line and have visceral innervation; therefore the most common presentation is painless bleeding. Because they are close to the anal transitional zone (ATZ), internal hemorrhoids can be covered by columnar, squamous, or basaloid cells. External hemorrhoids are located in the distal third of the anal canal and are covered by anoderm (squamous epithelium). Because of the somatic innervation of external hemorrhoids, patients who have these are more likely to be seen with pain (Fig. 26-1, B).

Office Procedures

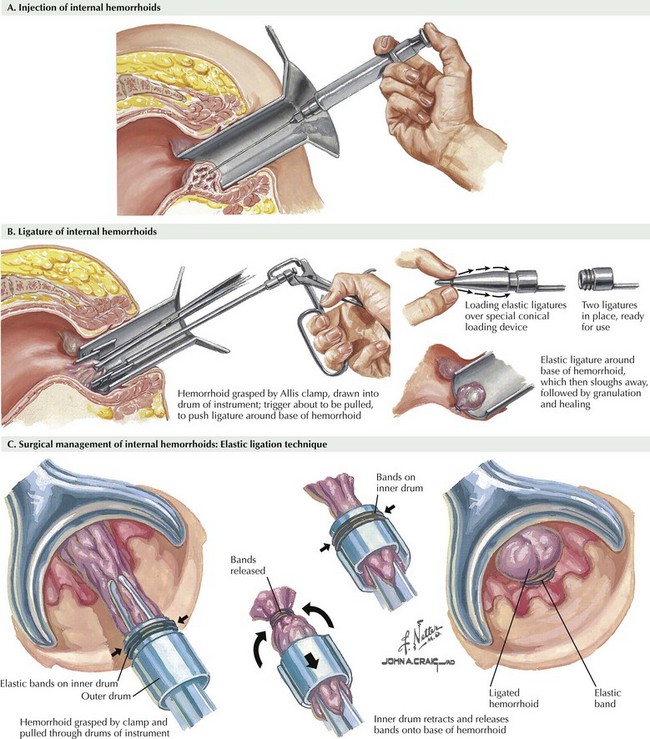

Rubber band ligation is the most frequently used procedure used in the United States. This technique is most often used to address 1st- and 2nd-degree hemorrhoids, although 3rd-degree hemorrhoids can occasionally be treated with this technique as well (Fig. 26-2, A). The rubber band necroses the intervening tissue over the course of 7 to 10 days and is passed in the patient’s stool. The most common of the many implements available for application of the rubber bands is a suction ligator, which allows the surgeon to draw in the hemorrhoidal tissue and apply the rubber band with one hand. Other devices require that the operator grasp the hemorrhoidal pile with a long forceps and apply the rubber band with the other hand (Fig. 26-2, B).

Hemorrhoidal banding controls bleeding in more than 90% of cases. Complications are rare but include vasovagal response, pain, bleeding, and pelvic sepsis. Most complications can be avoided by ensuring that the rubber band is placed well above the dentate line, close to the base of the hemorrhoidal pile (Fig. 26-2, C). Pelvic sepsis may result from incorporation of the distal rectal wall into the band. The combination of pain, urinary retention, and fever after banding should raise suspicion of pelvic sepsis.

Operative Hemorrhoidectomy

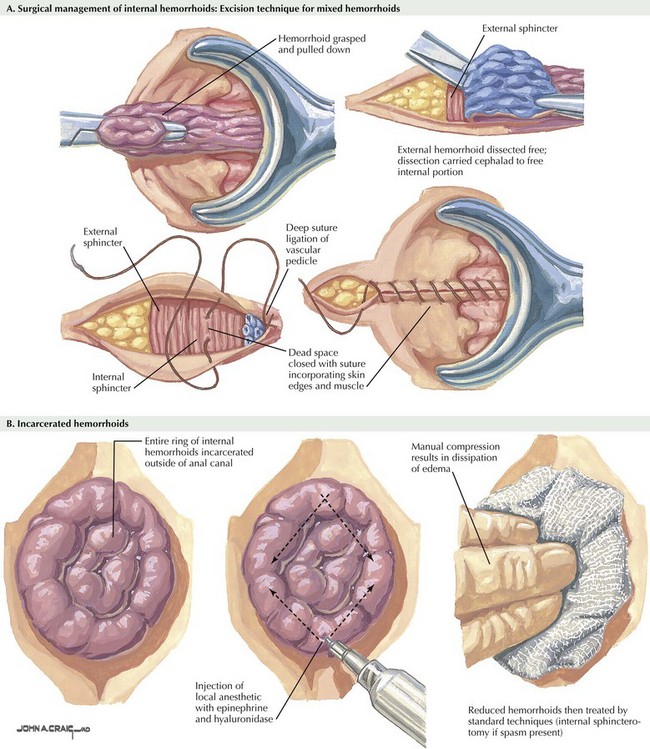

Patients for whom medical or nonsurgical therapies are not successful are candidates for operative hemorrhoidectomy. Typically, these patients have 3rd- or 4th-degree hemorrhoids. Fortunately, postsurgical recurrence is rare. The most common procedures are the Ferguson and Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy. Both techniques involve elliptical excision of the internal and external hemorrhoidal complex (Fig. 26-3, A).

Strangulated Hemorrhoids

Strangulated (or incarcerated) hemorrhoids are 3rd- or 4th-degree hemorrhoids that become thrombosed because of chronic prolapse and resultant swelling. Patients typically have severe anal pain and sometimes urinary retention. Physical examination typically reveals thrombosis of the internal and external hemorrhoids, with or without evidence of necrosis (Fig. 26-3, B).

Lestar, B, Pennickx, F, Kerremans, R. The composition of anal basal pressure: an in vivo and in vitro study in man. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:118–122.

Milligan, ET, Morgan, CN, Jones, LE. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal and the operative treatment of hemorrhoids. Lancet. 1937;2:119–124.

Schubert, MC, Sridhar, S, Schade, RR, Wexner, SD. What every gastroenterologist needs to know about common anorectal disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(26):3201–3209.

Su, MY, Chiu, CT, Wu, CS, et al. Endoscopic hemorrhoidal ligation of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Gastrointestinal Endosc. 2003;58:871–874.

Thomson, WH. The nature of haemorrhoids. Br J Surg. 1975;62:542–552.