Chapter 456 Hemoglobinopathies

456.1 Sickle Cell Disease

Clinical Manifestations and Treatment of Sickle Cell Anemia

Fever and Bacteremia

Fever in a child with sickle cell anemia is a medical emergency, requiring prompt medical evaluation and delivery of antibiotics due to the increased risk of bacterial infection and concomitant high fatality rate with infection. Several clinical management strategies have been developed for children with fever, ranging from admitting all patients with a fever for IV antimicrobial therapy to administering a 3rd-generation cephalosporin in an outpatient setting to patients without any of the previously established risk factors for occult bacteremia (Table 456-1). Given the observation that the average time for a positive blood culture with a bacterial pathogen is <20 hr in children with sickle cell anemia, admission for 24 hr is probably the most prudent strategy for children and families without a telephone or transportation, or with a history of inadequate follow-up. Outpatient management should be considered only for those with the lowest risk for bacteremia, and treatment choice should be considered carefully.

Table 456-1 CLINICAL FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH INCREASED RISK OF BACTEREMIA REQUIRING ADMISSION IN FEBRILE CHILDREN WITH SICKLE CELL DISEASE

Seriously ill appearance

Hypotension: systolic BP <70 mm Hg at 1 year of age or <70 mm Hg + 2 × the age in yr for older children

Poor perfusion: capillary-refill time >4 sec

Temperature >40.0°C

A corrected white-cell count >30,000/mm3 or <500/mm3

Platelet count <100,000/mm3

History of pneumococcal sepsis

Severe pain

Dehydration: poor skin turgor, dry mucous membranes, history of poor fluid intake, or decreased output of urine

Infiltration of a segment or a larger portion of the lung

Hemoglobin level <5.0 g/dL

BP, blood pressure.

From Williams JA, Flynn PM, Harris S et al: A randomized study of outpatient treatment with ceftriaxone for selected febrile children with sickle cell disease, N Engl J Med 329:472–476, 1993.

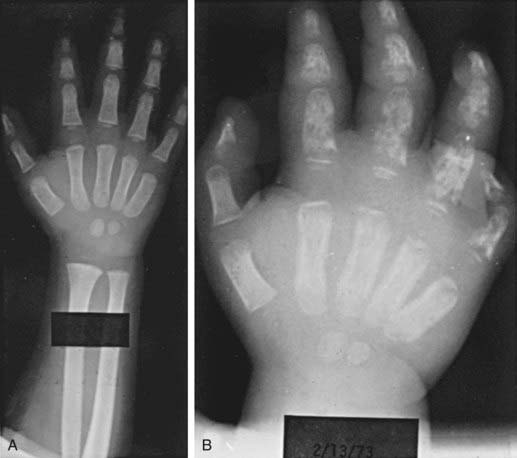

Dactylitis

Dactylitis, often referred to as hand-foot syndrome, is often the first manifestation of pain in children with sickle cell anemia, occurring in 50% of children by their 2nd year (Fig. 456-1). Dactylitis often manifests with symmetric or unilateral swelling of the hands and/or feet. Unilateral dactylitis can be confused with osteomyelitis, and careful evaluation to distinguish between the two is important, because treatment differs significantly. Dactylitis requires palliation with pain medications, such as acetaminophen with codeine, whereas osteomyelitis requires at least 4-6 wk of IV antibiotics.

Pain

Some patients require hospitalization for administration of IV morphine or derivatives of morphine. The incremental increase and decrease in the use of the medication to relieve pain roughly parallels the 8 phases associated with a chronology of pain and comfort (Table 456-2). The average hospital length of stay for children admitted in pain is 4.4 days. The American Pain Society has published clinical guidelines for treating acute and chronic pain in patients with sickle cell disease of any type. These recommendations are comprehensive and represent a starting point for treating pain (www.ampainsoc.org/pub/sc.htm).

Table 456-2 SUMMARY OF THE CHRONOLOGY OF PAIN IN CHILDREN WITH SICKLE CELL DISEASE

| PHASE | PAIN CHARACTERISTICS | SUGGESTED COMFORT MEASURES USED |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (Baseline) | No vaso-occlusive pain; pain of complications may be present, such as that connected with avascular necrosis of the hip | No comfort measures used |

| 2 (Pre-pain) | No vaso-occlusive pain; pain of complications may be present; prodromal signs of impending vaso-occlusive episode may appear, e.g., “yellow eyes” and/or fatigue | No comfort measures used; caregivers may encourage child to increase fluids to prevent pain event from occurring |

| 3 (Pain start point) | First signs of vaso-occlusive pain appear, usually in mild form | Mild oral analgesic often given; fluids increased; child usually maintains normal activities |

| 4 (Pain acceleration) | Intensive of pain increases from mild to moderate Some children skip this level or move quickly from phase 3 to phase 5 |

Stronger oral analgesic are given; rubbing, heat, or other activities are often used; child usually stays in school until the pain becomes more severe, then stays home and limits activities; is usually in bed; family searches for ways to control the pain |

| 5 (Peak pain experience) | Pain accelerates to high moderate or severe levels and plateaus; pain can remain elevated for extended period Child’s appearance, behavior, and mood are significantly different from normal |

Oral analgesics are given around the clock at home; combination of comfort measures is used; family might avoid going to the hospital; if pain is very distressing to the child, parent takes the child to the emergency department After child enters the hospital, families often turn over comforting activities to health care providers and wait to see if the analgesics work Family caregivers are often exhausted from caring for the child for several days with little or no rest |

| 6 (Pain decrease start point) | Pain finally begins to decrease in intensity from the peak pain level | Family caregivers again become active in comforting the child but not as intensely as during phases 4 and 5 |

| 7 (Steady pain decline) | Pain decreases more rapidly, become more tolerable for the child Child and family are more relaxed |

Health care providers begin to wean the child from the IV analgesic; oral opioids given; discharge planning is started Children may be discharged before they are pain free |

| 8 (Pain resolution) | Pain intensity is at a tolerable level, and discharge is imminent Child looks and acts like “normal” self Mood improves |

May receive oral analgesics |

Adapted from Beyer JE, Simmons LE, Woods GM, et al: A chronology of pain and comfort in children with sickle cell disease, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 153:913–920, 1999.

Neurologic Complications

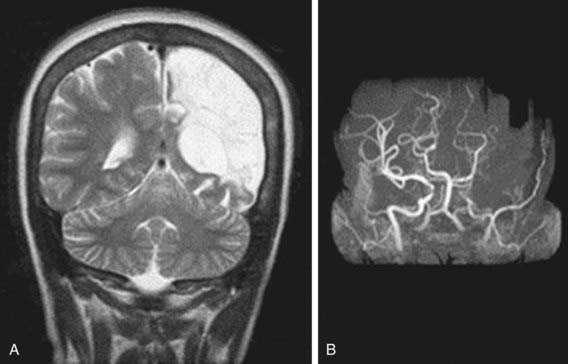

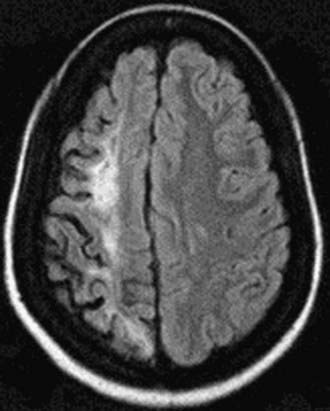

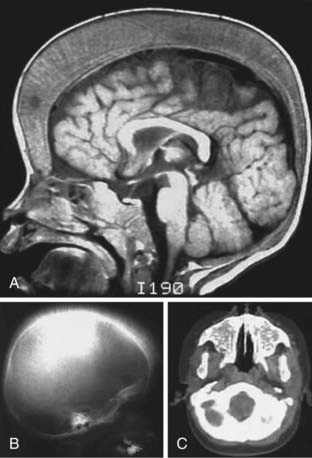

Neurologic complications associated with sickle cell anemia are varied and complex. Approximately 11% and 20% of children with sickle cell anemia will have overt and silent strokes, respectively, before their 18th birthday (Figs. 456-2 and 456-3). An overt stroke is defined as a focal neurologic deficit lasting >24 hr. However, this definition is outdated because many patients with sickle cell anemia will be treated with blood therapy that can hasten their recovery to baseline. A more functional definition is the presence of a focal neurologic deficit that lasts for >24 hr and/or increased signal intensity with a T2-weighted MRI of the brain indicating a cerebral infarct, corresponding to the focal neurologic deficit. The definition of silent cerebral infarct is the absence of a focal neurologic deficit lasting >24 hr in the presence of a lesion on T2-weighted MRI indicating a cerebral infarct. Evidence of a stroke can be found as early as 1 yr of age. Other neurologic complications include headaches that may or may not be related to sickle cell anemia, seizures, cerebral venous thrombosis, and reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS). Children with other types of sickle cell disease such as Hb SC or Hb Sβ-thalassemia plus might have overt or silent cerebral infarcts as well.

Lung Disease

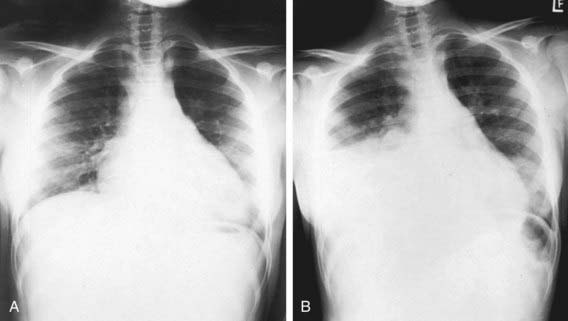

Lung disease in children with sickle cell anemia is the second most common reason for admission to the hospital and a common cause of death. ACS refers to a constellation of findings that include a new radiodensity on chest radiograph, fever, respiratory distress, and pain that occurs often in the chest, but it can also include the back and/or abdomen only (Fig. 456-4). Even in the absence of respiratory symptoms, all patients with fever should receive a chest radiograph to identify ACS because clinical examination alone is insufficient to identify patients with a new radiographic density, and early detection of acute syndrome will alter clinical management. The radiographic findings in ACS are variable but can include involvement of a single lobe (predominantly the left lower lobe) or multiple lobes (most often both lower lobes) and pleural effusions (either unilateral or bilateral).

Given the clinical overlap between ACS and common pulmonary complications such as bronchiolitis, asthma, and pneumonia, a wide range of therapeutic strategies have been used (Table 456-3). Oxygen administration and blood transfusion therapy, either simple or exchange (manual or automated), are the most common interventions used to treat ACS. Supplemental oxygen should be administered when the room air oxygen saturation is >90%. The decision about when to give blood and whether the transfusion should be a simple or exchange transfusion is less clearly defined. Commonly, blood transfusions are given when at least one of the following clinical features is present: decreasing oxygen saturation, increase work of breathing, rapid change in respiratory effort either with or without a worsening chest radiograph, or previous history of severe ACS requiring admission to the intensive care unit.

Table 456-3 OVERALL STRATEGIES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE CHEST SYNDROME

PREVENTION

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING AND LABORATORY MONITORING

TREATMENT

Diagnosis

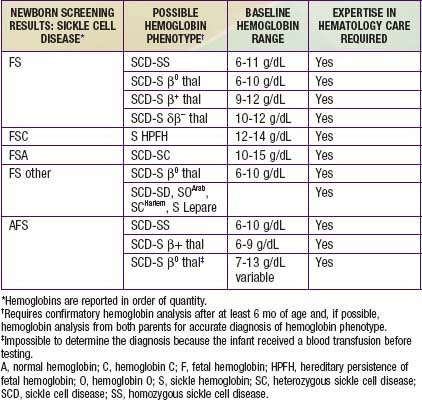

The most commonly used procedures for newborn diagnosis include thin layer/isoelectric focusing and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). A 2-step system is recommended, with all patients who have initially abnormal screens being retested during the first clinical visit and after 6 mo of age to determine the final hemoglobin phenotype. In addition, a complete blood cell count (CBC) and hemoglobin analysis are recommended on both parents to confirm the diagnosis and to provide an opportunity for genetic counseling. Table 456-4 correlates the initial hemoglobin phenotype at birth with the type of hemoglobinopathy, baseline hemoglobin range, and requirement for a hematologist.

Adams RJ, Brambilla DJ, Granger S, et al. STOP Study. Stroke and conversion to high risk in children screened with transcranial Doppler ultrasound during the STOP study. Blood. 2004;103:3689-3694.

American College of Pathologists. Sickle cell trait and the athlete (website), July 11, www.cap.org/apps/portlets/contentViewer/show.do?printFriendly=true&contentReference=statements%2Fsickle_cell_and_the_athlete_statement.html, 2007. Accessed June 20, 2010

Austin H, Key NS, Benson JM, et al. Sickle cell trait and the risk of venous thromboembolism among blacks. Blood. 2007;110:908-912.

Berger E, Saunders N, Wang L, Friedman JN. Sickle cell disease in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:251-255.

Brawley OW, Cornelius LJ, Edwards LR, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development conference statement: hydroxyurea treatment for sickle cell disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:932-938.

Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA. 2010;303:1288-1294.

Buchanan ID, Woodward M, Reed GW. Opioid selection during sickle cell pain crisis and its impact on the development of acute chest syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:716-724.

Chaudry RA, Cikes M, Karu T, et al. Paediatric sickle cell disease: pulmonary hypertension but normal vascular resistance. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:131-136.

de Montalembert M. Management of sickle cell disease. BMJ. 2008;337:626-630.

Dick MC. Standards for the management of sickle cell disease in children. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2009;93:169-176.

Dowling MM, Lee N, Quinn CT, et al. Prevalence of intracardiac shunting in children with sickle cell disease and stroke. J Pediatr. 2010;156:645-650.

Drotar D. Treatment adherence in patients with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr. 2010;156:350-351.

Eichner ER. Sickle cell trait. J Sport Rehab. 2007;16:197-203.

Enninful-Eghan H, Moore RH, Ichord R, et al. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography and prophylactic transfusion program is effective in preventing overt stroke in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 2010;157:479-484.

Frei-Jones M, Baxter AL, Rogers ZR, et al. Vaso-occlusive episodes in older children with sickle cell disease: emergency department management and pain assessment. J Pediatr. 2008;152:281-285.

Gladwin MT, Vichinsky E. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2254-2265.

Halasa NB, Shankar SM, Talbot TR, et al. Incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease among individuals with sickle cell disease before and after the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1428-1433.

Hankins J, Ware RE. Sickle-cell disease: an ounce of prevention, a pound of cure. Lancet. 2009;374:1308-1310.

Henderson JN, Noetzel MJ, McKinstry RC, et al. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome and silent cerebral infarcts are associated with severe acute chest syndrome in children with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2003;101:415-419.

Hsieh MM, Kang EM, Fitzhugh CD, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2309-2317.

Jain R, Sawhnet S, Rizvi SG. Acute bone crisis in sickle cell disease: the T1 fat-saturated sequence in differentiation of acute bone infarcts from acute osteomyelitis. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:59-70.

Jordan LC, McKinstry RC, Kraut MA, et al. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging of children with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):53-61.

Komba AN, Makani J, Sadarangani M, et al. Malaria as a cause of morbidity and mortality in children with homozygous sickle cell disease on the coast of Kenya. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:216-222.

Kopecky EA, Jacobson S, Joshi P, Koren G. Systemic exposure to morphine and the risk of acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;75:140-146.

Krishnamurti L, Bunn HF, Williams AM, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for hemoglobinopathies. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2008;38:1-28.

Maigne G, Ferlicot S, Galacteros F, et al. Glomerular lesions in patients with sickle cell disease. Medicine. 2010;89:18-27.

Mazumdar M, Heeney MM, Sox CM, et al. Preventing stroke among children with sickle cell anemia: an analysis of strategies that involve transcranial Doppler testing and chronic transfusion. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1107-e1116.

McCavit TL, Quinn CT, Techasaensiri C, et al. Increase in invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in children with sickle cell disease since pneumococcal conjugate vaccine licensure. J Pediatr. 2011;158:505-507.

National Athletic Trainers Association. Consensus statement: Sickle cell trait and the athlete (website). www.nata.org/statements/consensus/sicklecell.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2010

Neumayr L, Pringle S, Giles S, et al. Chart Card: feasibility of a tool for improving emergency department care in sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:1017-1023.

Niebanck AE, Pollock AN, Smith-Whitely K, et al. Headache in children with sickle cell disease: prevalence and associated factors. J Pediatr. 2007;151:67-72.

Norris CF, Smith-Whitley K, McGowan K. Positive blood cultures in sickle cell disease: time to positivity and clinical outcome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;5:390-395.

Okpala I, Westerdale N, Jegede T, et al. Etilefrine for the prevention of priapism in adult sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:918-921.

Patel K, Livni N, Macdonald D. Renal medullary carcinoma, a rare cause of haematuria in sickle cell trait. Br J Haematol. 2005;132(1):1.

Platt OS. Hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(13):1362-1369.

Quillen K, Lane C, Hu E, et al. Prevalence of ceftriaxone-induced red blood cell antibodies in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:357-358.

Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, et al. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;115(17):3447-3452.

Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376:2018-2031.

Rogers ZR. Priapism in sickle cell disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2005;19:917-928.

Saad ST, Lajolo C, Gilli S, et al. Follow-up of sickle cell disease patients with priapism treated by hydroxyurea. Am J Hematol. 2004;77:45-49.

Savitt TL. Tracking down the first recorded sickle cell patient in western medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(11):981-992.

Scothorn DJ, Price C, Schwartz D, et al. Risk of recurrent stroke in children with sickle cell disease receiving blood transfusion therapy for at least five years after initial stroke. J Pediatr. 2002;140:348-354.

Sebire G, Tabarki B, Saunders DE, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in children: risk factors, presentation, diagnosis and outcome. Brain. 2005;128:477-489.

Smith WR, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, et al. Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:94-101.

Smith-Whitley K, Zhao H, Hodinka RL, et al. Epidemiology of human parvovirus B19 in children with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2004;103:422-427.

Stanton MV, Janassaint CR, Bartholomew FB, et al. The association of optimism and perceived discrimination with health care utilization in adults with sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(11):1056-1063.

Strouse JJ, Lanzkron S, Beach MC, et al. Hydroxyurea for sickle cell disease: a systematic review for efficacy and toxicity in children. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1332-1342.

Telfer P, Criddle J, Sandell J, et al. Intranasal diamorphine for acute sickle cell pain. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:979-980.

Tripette J, Loko G, Samb A, et al. Effects of hydration and dehydration on blood rheology in sickle cell trait carriers during exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Cir Physiol. 2010;209:H908-H914.

Tsaras G, Owusu-Ansah A, Boateng FO, et al. Complications associated with sickle cell trait: a brief narrative review. Am J Med. 2009;122:507-512.

Vargas-Gonzalez R, Sotelo-Avila C, Coria AS. Case report: renal medullary carcinoma in a six-year-old boy with sickle cell trait. Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;9:193-195.

Vichinsky E, Onyekwere O, Porter J. A randomized comparison of deferasirox versus deferoxamine for the treatment of transfusional iron overload in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:501-508.

Vichinsky EP, Neumayr LD, Earles AN, et al. Causes and outcomes of the acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1855-1865.

Vichinsky EP, Neumayr LD, Gold JL, et al. Neuropsychological dysfunction and neuroimaging abnormalities in neurologically intact adults with sickle cell anemia. JAMA. 2010;303:1823-1831.

Villavicencio K, Ivy D, Cole L, et al. Symptomatic pulmonary hypertension in a child with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 2008;152:879-881.

Ware RE, Rees RC, Sarnaik SA, et al. Renal function in infants with sickle cell anemia: baseline data from the BABY HUG trial. J Pediatr. 2010;156:66-70.

Ware RE, Zimmerman SA, Sylvestre PB, et al. Prevention of secondary stroke and resolution of transfusional iron overload in children with sickle cell anemia using hydroxyurea and phlebotomy. J Pediatr. 2004;145:346-352.

Williams TN, Uyoga S, Macharia A, et al. Bacteremia in Kenyan children with sickle-cell anaemia: a retrospective cohort and case-control study. Lancet. 2009;374:1364-1370.

Wood JC, Enriquez C, Ghugre N, et al. MRI R2 and R2* mapping accurately estimates hepatic iron concentration in transfusion-dependent thalassemia and sickle cell disease patients. Blood. 2005;106:1460-1465.

Yanni E, Grosse SD, Yang Q, Olney RS. Trends in pediatric sickle cell disease–related mortality in the United States, 1983–2002. J Pediatr. 2009;154:541-545.

Zempsky WT. Treatment of sickle cell pain. JAMA. 2009;22:2479-2480.

Zhang Y, Dai Y, Wen J, et al. Detrimental effects of adenosine signaling in sickle cell disease. Nat Med. 2011;17(1):79-86.

456.2 Sickle Cell Trait (Hemoglobin AS)

Michael R. DeBaun, Melissa Frei-Jones, and Elliott Vichinsky

The amount of Hb S is influenced by the number of α-thalassemia genes present, and the amount in most persons with sickle cell trait (Hb AS) is <50%. The life span of people with sickle cell trait is normal, and serious complications are very rare. The CBC is within the normal range. Hemoglobin analysis is diagnostic, revealing a predominance of Hb A, typically >50%, and Hb S <50%. Complications of sickle cell trait include sudden death during rigorous exercise, splenic infarcts at high altitude, hematuria, hyposthenuria, bacteriuria, and susceptibility to eye injury with formation of a hyphema (Table 456-5). Renal medullary carcinoma is also associated with sickle cell trait and occurs predominantly in young adults and children.

Table 456-5 COMPLICATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH SICKLE CELL TRAIT

DEFINITE ASSOCIATIONS

PROBABLE ASSOCIATIONS

POSSIBLE ASSOCIATIONS

UNLIKELY OR UNPROVEN ASSOCIATIONS

From Tsaras G, Owusu-Ansah A, Boateng O, et al: Complications associated with sickle cell trait: a brief narrative review, Am J Med 122:507–512, 2009.

The National Association of Athletic Trainers (NATA) has made specific recommendations for the training of athletes with sickle cell trait, including the rapid recognition and treatment of exertional sickling or sickling collapse, which occurs when sickled RBCs occlude vessels and lead to ischemic rhabdomyolysis (Table 456-6). An important component of the screening of athletes is that adequate knowledge about sickle cell trait status identified at birth is later communicated to the adolescent before transitioning to adulthood.

Table 456-6 NATIONAL ATHLETIC TRAINER’S ASSOCIATION GUIDELINES FOR ATHLETES WITH SICKLE CELL TRAIT

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ATHLETES WITH SICKLE CELL TRAIT

There is no contraindication to participation in sport for the athlete with sickle cell trait.

Red blood cells can sickle during intense exertion, blocking blood vessels and posing a grave risk for athletes with sickle cell trait.

Screening and simple precautions may prevent deaths and help athletes with sickle cell trait thrive in their sport.

Efforts to document newborn screening results should be made during the pre-sports physical exam (PPE).

In the absence of newborn screening results, institutions should carefully weigh the decision to screen based on the potential to provide key clinical information and targeted education that may save lives.

Irrespective of screening, institutions should educate staff, coaches, and athletes on the potentially lethal nature of this condition.

Education and precautions work best when targeted at those athletes who need it most; therefore, institutions should carefully weigh this factor in deciding whether to screen. All told, the case for screening is strong.

| SYMPTOMS OF SICKLING COLLAPSE* VERSUS HEAT CRAMPING | |

|---|---|

| Sickling Collapse | Heat Cramping |

| No prodrome | Prodrome of muscle twinges |

| Pain is less excruciating | Pain is more excruciating |

| Sickling players slump to the ground with weak muscles | Athletes stop due to “locked-up” muscles |

| Athletes with sickling lie fairly still, not yelling in pain, with muscles that look and feel normal | Athletes writhe and yell in pain, with muscles visibly contracted and rock-hard |

| If caught early, sickling players recover faster | Even with treatment heat cramping has delayed resolution |

PREVENTION OF SICKLING COLLAPSE*

Build up slowly in training with paced progressions, allowing longer periods of rest and recovery between repetitions.

Encourage participation in preseason strength and conditioning programs to enhance the preparedness of athletes for performance testing, which should be sports-specific. Athletes with sickle cell trait should be excluded from participation in performance tests such as mile runs, serial sprints, etc., as several deaths have occurred from participation in this setting.

Cessation of activity with onset of symptoms: muscle “cramping,” pain, swelling, weakness, tenderness, inability to “catch breath,” or fatigue

If sickle-trait athletes can set their own pace, they seem to do fine.

All athletes should participate in a year-round, periodized strength and conditioning program that is consistent with individual needs, goals, abilities, and sport-specific demands. Athletes with sickle cell trait who perform repetitive high speed sprints and/or interval training that induces high levels of lactic acid should be allowed extended recovery between repetitions since this type of conditioning poses special risk to these athletes.

Ambient heat stress, dehydration, asthma, illness, and altitude predispose the athlete with sickle trait to an onset of crisis in physical exertion.

Educate to create an environment that encourages athletes with sickle cell trait to report any symptoms immediately; any signs or symptoms such as fatigue, difficulty breathing, leg or low back pain, or leg or low back cramping in an athlete with sickle cell trait should be assumed to be sickling.

TREATMENT OF SICKLING COLLAPSE*

Check vital signs.

Administer high-flow oxygen, 15 L/min (if available), with a non-rebreather face mask.

Cool the athlete, if necessary.

If the athlete is obtunded or as vital signs decline, call 911, attach an automated external defibrillator, start an IV, and get the athlete to the hospital fast.

Tell the doctors to expect explosive rhabdomyolysis and grave metabolic complications.

Proactively prepare by having an emergency action plan and appropriate emergency equipment for all practices and competitions.

* Sickling collapse or exertional sickling occurs when sickled red blood cells accumulate in the blood stream during intense exercise and cause ischemic rhabdomyolysis, precipitating severe metabolic consequences.

456.3 Other Hemoglobinopathies

Michael R. DeBaun, Melissa Frei-Jones, and Elliott Vichinsky

456.4 Unstable Hemoglobin Disorders

Michael R. DeBaun, Melissa Frei-Jones, and Elliott Vichinsky

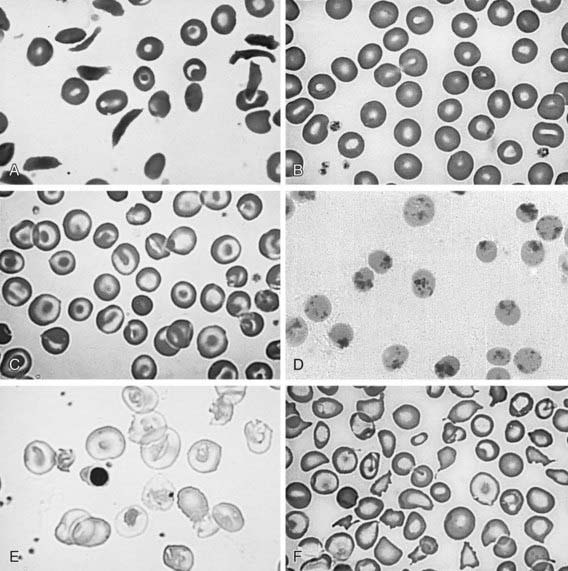

At least 200 rare unstable hemoglobins have been identified; the most common is Hb Köln. Most patients seem to have de novo mutations rather than inherited hemoglobin disorders. Unstable hemoglobins whose mutation causes unstable heme binding eventually leading to the denaturation of the hemoglobin molecule are the best studied. The denatured hemoglobin can be visualized during severe hemolysis or after splenectomy as Heinz bodies. Unlike the Heinz bodies seen after toxic exposure, in unstable hemoglobins, Heinz bodies are present in reticulocytes and older red cells (Fig. 456-5). Heterozygotes are asymptomatic.

456.5 Abnormal Hemoglobins with Increased Oxygen Affinity

Michael R. DeBaun, Melissa Frei-Jones, and Elliott Vichinsky

456.6 Abnormal Hemoglobins Causing Cyanosis

Michael R. DeBaun, Melissa Frei-Jones, and Elliott Vichinsky

456.7 Hereditary Methemoglobinemia

MetHb may be increased in the red cell owing to exposure to toxic substances or to absence of reductive pathways, such as NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase deficiency. Toxic methemoglobinemia is much more common than hereditary methemoglobinemia (Table 456-7). Infants are particularly vulnerable to hemoglobin oxidation because their RBCs have half the amount of cytochrome b5 reductase seen in adults; fetal hemoglobin is more susceptible to oxidation than hemoglobin A; and the more alkaline infant gastrointestinal tract promotes the growth of nitrite-producing gram-negative bacteria. When MetHb levels are >1.5 g/24 hr, cyanosis is visible (15% MetHb); a level of 70% MetHb is lethal. The level is usually reported as a percentage of normal hemoglobin, and the toxic level is lower at a lower hemoglobin level. Methemoglobinemia has been described in infants who ingested foods and water high in nitrates, who were exposed to aniline teething gels or other chemicals, and in some infants with severe gastroenteritis and acidosis. Methemoglobin can color the blood brown (Fig. 456-6).

Table 456-7 KNOWN ETIOLOGIES OF ACQUIRED METHEMOGLOBINEMIA

MEDICATIONS

MEDICAL CONDITIONS

MISCELLANEOUS

From Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM: Acquired methemoglobinemia, Medicine 83:265–273, 2004.

Hereditary Methemoglobinemia with Deficiency of NADH Cytochrome B5 Reductase

Clinically, cyanosis varies in intensity with season and diet. Methemoglobin can color the blood brown (see Fig. 456-6). The time at onset of cyanosis also varies; in some patients it appears at birth, in others as late as adolescence. Although as much as 50% of the total circulating hemoglobin may be in the form of nonfunctional methemoglobin, little or no cardiorespiratory distress occurs in these patients, except on exertion.

456.8 Syndromes of Hereditary Persistence of Fetal Hemoglobin

Michael R. DeBaun, Melissa Frei-Jones, and Elliott Vichinsky

HPFH syndromes are a form of thalassemia; mutations are associated with a decrease in the production of either or both β- and δ-globins. There is an imbalance in the α : non-α synthetic ratio (Chapter 456.9) characteristic of thalassemia. More than 20 variants of HPFH have been described. They are deletional, δβ0 (Black, Ghanaian, Italian), nondeletional (Tunisian, Japanese, Australian), linked to the β-globin-gene cluster (British, Italian-Chinese, Black), or unlinked to the β-globin-gene cluster (Atlanta, Czech, Seattle). The δβ0 forms have deletions of the entire δ- and β-gene sequences, and the most common form in the United States is the Black (HPFH 1) variant. As a result of the δ and β gene deletions, there is production only of γ-globin and formation of Hb F. In the homozygous form, no manifestations of thalassemia are present. There is only Hb F with very mild anemia and slight microcytosis. When inherited with other variant hemoglobins, Hb F is elevated into the 20-30% range; when inherited with Hb S, there is an amelioration of sickle cell disease with fewer complications.

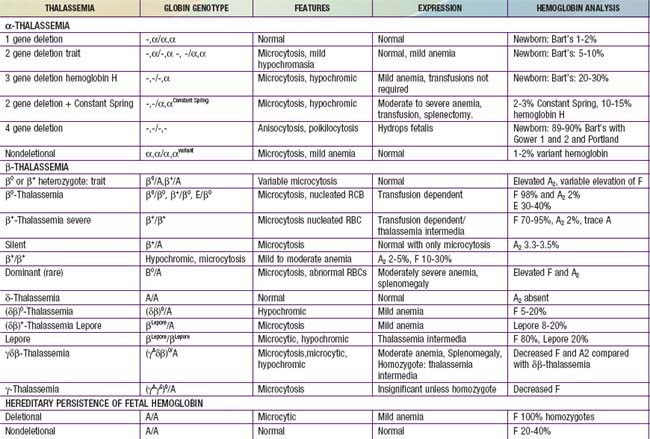

456.9 Thalassemia Syndromes

Pathophysiology

Two related features contribute to the sequelae of β-thalassemia: inadequate β-globin gene production leading to decreased levels of normal hemoglobin (Hb A) and unbalanced α- and β-globin chain production. Selected features of thalassemia can be seen in Table 456-8. In the bone marrow, thalassemia mutations disrupt the maturation of erythrocytes, resulting in ineffective erythropoiesis; the marrow is hyperactive, but there are relatively few reticulocytes and severe anemia exists. In β-thalassemia, there is an excess of α-globin chains relative to β- and γ-globin chains, and α-globin tetramers (α4) are formed. These inclusions interact with the red cell membrane and shorten red cell survival, leading to anemia and increased erythroid production. The γ-globin chains are produced in increased amounts, leading to an elevated Hb F (α2γ2). The δ-globin chains are also produced in increased amounts, leading to an elevated Hb A2 (α2δ2) in β-thalassemia.

Homozygous β-Thalassemia (Thalassemia Major, Cooley Anemia)

Clinical Manifestations

Most infants and children have cardiac decompensation at hemoglobins of 4 g/dL or less. Generally, fatigue, poor appetite, and lethargy are late findings of severe anemia in an infant or child and were more common before transfusions were standard therapy. The classic presentation of children with severe disease includes thalassemic facies (maxilla hyperplasia, flat nasal bridge, frontal bossing), pathologic bone fractures, marked hepatosplenomegaly, and cachexia and is now primarily seen in developing countries. The spleen can become so enlarged that it causes mechanical discomfort and secondary hypersplenism. The features of ineffective erythropoiesis include expanded medullary spaces (with massive expansion of the marrow of the face and skull producing the characteristic thalassemic facies), extramedullary hematopoiesis, and higher metabolic needs (Fig. 456-7). The hepatosplenomegaly can interfere with nutritional support. Pallor, hemosiderosis, and jaundice can combine to produce a greenish brown complexion.

Laboratory Findings

The infant is born only with Hb F or, in some cases, Hb F and Hb E (heterozygosity for β-thalassemia zero). Eventually, there is severe anemia, reticulocytopenia, numerous nucleated erythrocytes, and microcytosis with almost no normal-appearing erythrocytes on the peripheral smear (see Fig. 456-5E). The hemoglobin level falls progressively to <5 g/dL unless transfusions are given. The reticulocyte count is commonly <8% and is inappropriately low when compared to the degree of anemia due to ineffective erythropoiesis. The unconjugated serum bilirubin level is usually elevated, but other chemistries may be normal at an early stage. Even if the child does not receive transfusions, eventually there is iron accumulation with elevated serum ferritin and transferrin saturation. Bone marrow hyperplasia can be seen on radiographs (see Fig. 456-7).

α-Thalassemia

The α-thalassemia traits manifest as a microcytic anemia that can be mistaken for iron-deficiency anemia (see Fig. 456-5F). The hemoglobin analysis is normal, except during the newborn period, when Hb Bart’s is commonly <8% but >3%. Children with a deletion of 2 α-globin genes are commonly thought to have iron deficiency, given the presence of both low MCV and MCH. The simplest approach to distinguish between iron deficiency and α-thalassemia trait is with a good dietary history. Children with iron-deficiency anemia often have a diet that is low in iron. Alternatively, a brief course of iron supplementation along with monitoring of erythrocyte parameters might confirm the diagnosis of iron deficiency, or α-globin gene deletion analysis may be necessary.

Aessopos A, Tsironi M, Vassiliadis I, et al. Exercise-induced myocardial perfusion abnormalities in sickle beta-thalassemia: Tc-99m tetrofosmin gated SPECT imaging study. Am J Med. 2001;111:355-360.

Berkovitch M, Bistritzer T, Milone SD, et al. Iron deposition in the anterior pituitary in homozygous beta-thalassemia: MRI evaluation and correlation with gonadal function. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000;13:179-184.

Cappellini MD, Cohen A, Piga A, et al. A phase 3 study of deferasirox (ICL670), a once-daily oral iron chelator, in patients with beta-thalassemia. Blood. 2006;107:3455-3462.

Chen FE, Ooi C, Ha SY, et al. Genetic and clinical features of hemoglobin H disease in Chinese patients. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:544-550.

Chern JP, Lin KH, Lu MY, et al. Abnormal glucose tolerance in transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemic patients. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:850-854.

Chirnomas D, Smith AL, Braunstein J, et al. Deferasirox pharmacokinetics in patients with adequate vs. inadequate response. Blood. 2009;114:4009-4013.

Chui DHK, Fuchareon S, Chan V. Hemoglobin H disease: not necessarily a benign disorder. Blood. 2003;101:791-800.

Eldor A, Rachmilewitz EA. The hypercoagulable state in thalassemia. Blood. 2002;99:36-43.

Gulati R, Bhatia V, Agarwal SS. Early onset of endocrine abnormalities in beta-thalassemia major in a developing country. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000;13:651-656.

Hahalis G, Manolis AS, Gerasimidou I, et al. Right ventricular diastolic function in beta-thalassemia major: echocardiographic and clinical correlates. Am Heart J. 2001;141:428-434.

Kattamis AC, Antoniadis M, Manoli I, et al. Endocrine problems in ex-thalassemic patients. Transfus Sci. 2000;23:251-252.

Lal A, Goldrich ML, Haines DA, et al. Heterogeneity of hemoglobin H disease in childhood. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(8):710-718.

Lorey F, Cunningham G, Vichinsky EP, et al. Universal newborn screening for Hb H disease in California. Genet Test. 2001;5:93-100.

Saini A, Chandra J, Goswami U, et al. Case control study of psychosocial morbidity in β thalassemia major. J Pediatr. 2007;150:516-520.

Telfer PT, Prestcott E, Holden S, et al. Hepatic iron concentration combined with long-term monitoring of serum ferritin to predict complications of iron overload in thalassaemia major. Br J Haematol. 2000;110:971-977.

Weatherall DJ. Introduction to the problem of hemoglobin E-beta thalassemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:551-553.

Winichagoon P, Fucharoen S, Chen P, et al. Genetic factors affecting clinical severity in beta-thalassemia syndromes. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:573-580.

Wonke B. Clinical management of beta-thalassemia major. Semin Hematol. 2001;38:350-359.

Andrews NC. Inherited iron overload disorders. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2000;12:596-602.

McCullen MA, Crawford DH, Hickman PE. Screening for hemochromatosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;315:169-186.

Murray KF, Kowdley KV. Neonatal hemochromatosis. Pediatrics. 2001;108:960-964.

Roy CN, Andrews NC. Recent advances in disorders of iron metabolism: mutations, mechanisms and modifiers. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2181-2186.

Sanchez AM, Schreiber GB, Bethel J, et al. Prevalence, donation practices, and risk assessment of blood donors with hemochromatosis. JAMA. 2001;286:1475-1481.

Vohra P, Haller C, Emre S, et al. Neonatal hemochromatosis: The importance of early recognition of liver failure. J Pediatr. 2000;136:537-541.