Chapter 23 Hemiplegia and Monoplegia

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

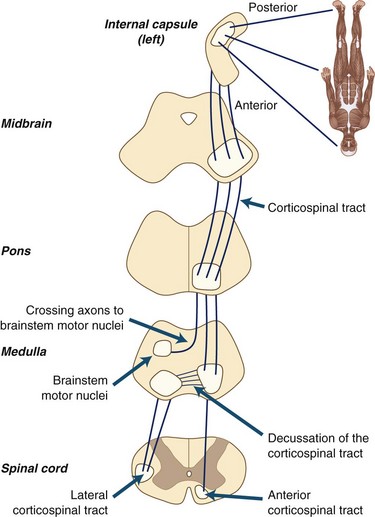

Hemiplegia and monoplegia are motor symptoms and signs, but associated sensory abnormalities are an aid to localization, so these are discussed when appropriate. Sensory deficit syndromes are discussed in more depth in Chapter 28. Motor power begins with volition, the conscious effort to initiate movement. Lack of volition does not produce weakness but rather results in akinesia. Projections from the premotor regions of the frontal lobes to the motor strip result in activation of corticospinal tract (CST) neurons. The descending fibers pass through the internal capsule and the cerebral peduncles, and then remain in the ventral brainstem before crossing in the medulla at the pyramidal decussation. Most of the CST crosses at this point, although a small subset of CST axons remains uncrossed until these axons reach the spinal segmental levels. Descending CST axons project to the spinal cord segments, where the fibers exit the CST and enter the spinal gray matter. Here, motoneurons are activated that then conduct action potentials via the motor axons to the muscle to produce muscle contraction.

Only hemiplegia and monoplegia are discussed in this chapter.

Hemiplegia

Cerebral Lesions

Cerebral lesions constitute the most common cause of hemiplegia. Lesions in either cortical or subcortical structures may be responsible for the weakness (Table 23.1).

| Lesion Location | Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|---|

| Motor cortex | Weakness and poor control of the affected extremity, which may involve face, arm, and leg to different degrees | Incoordination and weakness that depends on the location of the lesion within the cortical homunculus; often associated with neglect, apraxia, aphasia, or other signs of cortical dysfunction |

| Internal capsule | Weakness that usually affects the face, arm, and leg almost equally | Often associated with sensory impairment in same distribution |

| Basal ganglia | Weakness and incoordination on the contralateral side | Weakness, often without sensory loss; no neglect or aphasia |

| Thalamus | Sensory loss | Sensory loss with little or no weakness |

Cortical Lesions

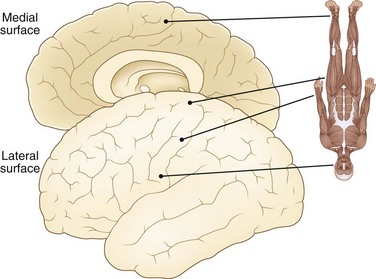

Cortical lesions produce weakness that is more focal than the weakness seen with subcortical lesions. Fig. 23.1 is a diagrammatic representation of the surface of the brain, showing how the body is mapped onto the surface of the motor sensory cortex; this is the homunculus. The face and arm are laterally represented on the hemisphere, whereas the leg is draped over the top of the hemisphere and into the interhemispheric fissure.

Subcortical Lesions

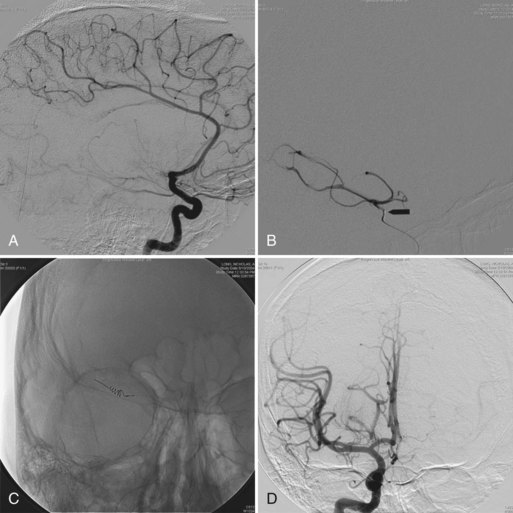

Infarction

Infarction usually is a clinical diagnosis but can be confirmed by CT or MRI scans, as discussed earlier (see Cortical Lesions). Infarction manifests with acute onset of deficit, although the course may be one of steady progression or stuttering. Lacunar infarctions are more likely than cortical infarctions to be associated with a stuttering course.

Lenticulostriate Arteries

Lenticulostriate arteries are small penetrating vessels that arise from the proximal MCA and supply the basal ganglia and internal capsule. Infarction commonly produces contralateral hemiparesis with little or no sensory involvement. This is one cause of the syndrome of pure motor stroke, which can also be due to a brainstem lacunar infarction (Lastilla, 2006).

Demyelinating Disease

Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a demyelinating illness that is monophasic but in other respects manifests like a first attack of MS (Wingerchuk, 2006). This entity sometimes is called parainfectious encephalomyelitis, although the association with infection is not always certain. Symptoms and signs at all levels of the central nervous system (CNS) are common, including hemiparesis, paraplegia, ataxia, and brainstem signs. Diagnosis is based on clinical grounds, because MRI scans cannot definitively distinguish between MS and ADEM. CSF examination may show a mononuclear pleocytosis and elevation in protein, but these findings are neither always present nor specific. Even the presence or absence of oligoclonal IgG in the CSF cannot differentiate between ADEM and MS. Patients who present clinically with ADEM should be warned of the possibility of having recurrent events indicative of MS.

Migraine

Migraine can be divided into many subdivisions, including the following:

All but common migraine can cause hemiplegia (Black, 2006). Common migraine is episodic headache without aura; by definition, there should be no deficit. Classic migraine is episodic headache with aura, most commonly visual. Basilar migraine is episodic headache with brainstem signs including vertigo and ataxia; this variant is a disorder mainly of childhood. Complicated migraine is that in which the aura lasts for hours or days beyond the duration of the headache. Hemiplegic migraine, as its name suggests, is characterized by paralysis of one side of the body, typically with onset before the headache; this variant often is familial. Migraine equivalent is characterized by the presence of episodic neurological symptoms without headache.

Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood is a rare condition characterized by attacks of unilateral weakness, often with signs of other motor deficits (e.g., dyskinesias, stiffness) and oculomotor abnormalities (e.g., nystagmus) (Zhang et al., 2003). Attacks begin in young childhood, usually before age 18 months; they last hours, and deficits accumulate over years. Initially, patients are normal, but with time, neurological deficits including motor deficits and cognitive decline become obvious. A benign form can occur on awakening in patients who are otherwise normal and do not develop progressive deficits; this entity is related to migraine. Diagnostic studies often are performed, including MRI, electroencephalography, and angiography, but these usually show no abnormalities. Alternating hemiplegia is suggested when a young child presents with episodes of hemiparesis, especially on awakening, not associated with headache.

Hemiconvulsion-Hemiplegia-Epilepsy Syndrome

In young children with the rare condition called hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia-epilepsy syndrome, unilateral weakness develops after the sudden onset of focal seizures. The seizures are often incompletely controlled. Neurological deficits are not confined to the motor system and may include cognitive, language, and visual deficits. Unlike alternating hemiplegia, the seizures and motor deficits are consistently unilateral, although eventually the unilateral seizures may become generalized. Imaging findings may be normal initially, but eventually atrophy of the affected hemisphere is seen (Freeman et al., 2002). CSF analysis is not specific, but a mild mononuclear pleocytosis may develop because of the CNS damage and seizures. Rasmussen encephalitis is a cause of this syndrome.

Brainstem Lesions

Brainstem Motor Organization

Fig. 23.2 shows the anatomical organization of the motor systems of the brainstem. Discussion of the complex anatomical organization of the brainstem can be simplified by concentrating on some important functions:

Common Lesions

Table 23.2 shows some of the important lesions of the brainstem and their associated motor deficits. Brainstem lesions usually are due to damage to the penetrating branches of the basilar artery. Patients present with contralateral weakness along with other deficits that help localize the lesion. Hemiataxia often develops and can be mistaken for hemiparesis, so careful examination is essential. Demyelinating disease and tumors are the other most common causes of brainstem dysfunction.

| Named Disorder | Lesion Location | Signs |

|---|---|---|

| MIDBRAIN | ||

| Weber syndrome | CN III, ventral midbrain, CST | Contralateral hemiparesis, CN III palsy |

| Benedikt syndrome | CN III, ventral midbrain, CST, red nucleus | Contralateral hemiparesis, third nerve palsy, intention tremor, cerebellar ataxia |

| Top-of-the-basilar syndrome | Occipital lobes, midbrain oculomotor nuclei, cerebral peduncle, medial and temporal lobe, thalamus | Contralateral hemiparesis, cortical blindness, oculomotor deficits, memory difficulty, contralateral sensory deficit |

| PONS | ||

| Millard-Gubler syndrome | CN VI, CN VII, ventral pons | Contralateral hemiparesis, CN VI and CN VII palsies |

| Clumsy hand syndrome | CST, CN VII | Contralateral hemiparesis, dysarthria, often with facial weakness |

| Pure motor hemiparesis (due to pons lesion) | Ventral pons | Contralateral hemiparesis with corticospinal tract signs |

| Ataxic hemiparesis (due to pons lesion) | CST, cerebellar tracts | Contralateral hemiparesis with impaired coordination |

| Foville syndrome | CN VII, ventral pons, paramedian pontine reticular formation | Ipsilateral CN VII palsy, contralateral hemiparesis, gaze palsy to the side of the lesion |

| MEDULLA | ||

| Medial medullary syndrome | CST, medial lemniscus, hypoglossal nerve | Contralateral hemiparesis, loss of position and vibratory sensation, ipsilateral tongue paresis |

| Lateral medullary syndrome | Spinothalamic tract, trigeminal nucleus, cerebellum and inferior cerebellar peduncle, vestibular nuclei, nucleus ambiguus | No hemiparesis usually produced, but hemiataxia may be mistaken for hemiparesis; dysphagia, hemisensory loss, face weakness, Horner syndrome are common |

CN, Cranial nerve; CST, corticospinal tract.

Spinal Lesions

Spinal Cord Compression

Spinal cord compression usually is due to disk protrusion, spondylosis, or acute trauma, but neoplastic and infectious causes should always be considered (Shedid and Bonzel, 2007). Disc disease and spondylosis typically are in the midline, so bilateral findings are expected. Extradural tumors also usually produce bilateral findings. Intradural tumors may produce unilateral deficits and occasionally can manifest as Brown-Séquard syndrome.

Peripheral Lesions

Mononeuropathy multiplex can manifest as separate lesions affecting individual limbs; involvement of an arm and leg on the same side can give the impression of hemiparesis. Diabetes is the most common cause, but other causes include leprosy, vasculitis, and predisposition to pressure palsies. Diagnosis is by electromyography (EMG), which can differentiate mononeuropathies from polyneuropathy (Misulis, 2003). Radiculopathy would not give hemiparesis but is a consideration in the differential diagnosis for monoplegia (see Radiculopathies, later in this chapter).

Functional Hemiplegia

Improvement in strength with coaching

Improvement in strength with coaching

Inconsistencies in examination—for example, inability to extend the foot but able to walk on toes

Inconsistencies in examination—for example, inability to extend the foot but able to walk on toes

Hoover sign (when the patient lies supine on the bed and lifts one leg at a time, the examiner should feel effort to press down with the opposite heel if the leg is truly paralyzed; failure to do so constitutes the Hoover sign)

Hoover sign (when the patient lies supine on the bed and lifts one leg at a time, the examiner should feel effort to press down with the opposite heel if the leg is truly paralyzed; failure to do so constitutes the Hoover sign)

Paralysis in the absence of other signs of motor system dysfunction, including tone and reflex changes

Paralysis in the absence of other signs of motor system dysfunction, including tone and reflex changes

Monoplegia

Cerebral Lesions

Infarction

The arm region of the motor cortex is supplied by the MCA. Infarction of a branch of the MCA can produce isolated arm weakness, although facial involvement and cortical signs are expected—language deficit with left hemisphere lesions and neglect with right hemisphere lesions (Paciaroni et al., 2005). With more extensive lesions, visual fields can be abnormal because of infarction of the optic radiations. Mild leg weakness also can occur with medial cortical involvement of the infarct. The leg segment of the cortex lies in the parasagittal region and is supplied by the ACA. ACA infarction produces weakness of the contralateral leg.

Peripheral Lesions

Pressure Palsies

Hereditary Neuropathy with Predisposition to Pressure Palsies

Hereditary neuropathy with predisposition to pressure palsies is associated with episodic weakness and sensory loss associated with compression of isolated nerves. This disorder is inherited as an autosomal dominant condition. Nerve conduction studies may show distal slowing of conduction velocities in affected nerves. NCVs also may be reduced in asymptomatic gene carriers (Chance, 2006).

Mononeuropathies

Table 23.3 shows some important peripheral nerve lesions of the arm. Table 23.4 shows some important peripheral nerve lesions of the leg.

| Lesion | Clinical Findings | Electromyography Findings |

|---|---|---|

| MEDIAN NEUROPATHY | ||

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Weakness and wasting of abductor pollicis brevis if severe; sensory loss on palmar aspect of first through third digits | Slow median motor and sensory NCV through the carpal tunnel; denervation of abductor pollicis brevis if severe |

| Anterior interosseous syndrome | Weakness of flexor digitorum profundus, pronator quadratus, flexor pollicis longus | Denervation in flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus |

| Pronator teres syndrome | Weakness of distal median-innervated muscles; tenderness of pronator teres | Slow median motor NCV through proximal forearm denervation of distal median-innervated muscles |

| Compression at the ligament of Struthers | Weakness of distal median-innervated muscles | As for pronator teres syndrome, with the addition of denervation of pronator teres |

| ULNAR NEUROPATHY | ||

| Palmar branch damage | Weakness of dorsal interossei; no sensory loss | Normal ulnar NCV; denervation of first dorsal interosseus but not abductor digiti minimi |

| Entrapment at Guyon canal | Weakness of ulnar intrinsic muscles; numbness over fourth and fifth digits | Slow ulnar motor and sensory NCV through wrist |

| Entrapment at or near the elbow | Weakness of ulnar intrinsic muscles; numbness over fourth and fifth digits | Slow ulnar motor NCV across elbow, denervation in first dorsal interosseus, abductor digiti minimi, and ulnar half of flexor digitorum profundus |

| RADIAL NEUROPATHY | ||

| Posterior interosseus syndrome | Weakness of finger and wrist extensors; no sensory loss | Denervation in wrist and finger extensors; sparing of the supinator and extensor carpi radialis |

| Compression at the spiral groove | Weakness of finger and wrist extensors; triceps usually spared; sensory loss on dorsal aspects of first digit | Slow radial motor NCV across spiral groove; denervation in distal radial-innervated muscles; triceps may be affected with proximal lesions |

NCV, Nerve conduction velocity.

Table 23.4 Peripheral Nerve Lesions of the Leg

| Lesion | Clinical Findings | Electromyography Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Sciatic neuropathy | Weakness of tibial- and peroneal-innervated muscles, with sensory loss on posterior leg and foot | Denervation distally in tibial- and peroneal-innervated muscles |

| Peroneal neuropathy | Weakness of foot extension and eversion and toe extension | Denervation in tibialis anterior; NCV across fibular neck may be slowed |

| Tibial neuropathy | Weakness of foot plantar flexion | Denervation of gastrocnemius |

| Femoral neuropathy | Weakness of knee extension; weakness of hip flexion if psoas involved | Denervation in quadriceps, sometimes psoas |

NCV, Nerve conduction velocity.

Sciatic Neuropathy

Sciatic neuropathy can have multiple causes, including acute trauma and chronic compressive lesions. The term sciatica describes pain in the distribution of the sciatic nerve in the back of the leg. It usually is due to radiculopathy (see Radiculopathies, later). An intramuscular injection into the sciatic nerve rather than the gluteus muscle is an occasional cause of sciatic neuropathy, which is characterized by initial severe pain followed by a lesser degree of pain and weakness.

Peroneal Neuropathy

Peroneal neuropathy can develop from a lesion at the fibular neck, the popliteal fossa, or even the sciatic nerve in the thigh. The peroneal division of the sciatic nerve is more susceptible to injury than the tibial division, so incomplete sciatic injury affects predominantly the peroneal nerve–innervated muscles. The peroneal nerve innervates the tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum brevis, and peroneus muscles. In addition, the peroneal division innervates the short head of the biceps femoris in the distal posterior thigh. This is an important muscle to remember because distal peroneal neuropathy spares this muscle, whereas a proximal sciatic neuropathy, a peroneal division lesion, or a radiculopathy is expected to cause denervation not only in the tibialis anterior but also the short head of the biceps femoris (Marciniak et al., 2005).

Radiculopathies

Radiculopathy produces weakness of one portion of a limb. Common radiculopathies are summarized in Table 23.5. Complete paralysis of all of the muscles of an arm or leg is not caused by radiculopathy, other than in traumatic avulsion of the nerve roots, which may occur in the upper limbs with distraction injuries of the arm from the neck. Roots serving arm power include chiefly C5 to T1. Roots serving leg power are chiefly L2 to S1. A lesion at the L5 level often elicits a complaint of weakness of the entire limb because of the foot drop, which interferes with gait. Reflex abnormalities often are present early in a radiculopathy and are a manifestation of the sensory component. Motor deficits develop with increasingly severe radiculopathy.

| Level | Motor Deficit | Sensory Deficit |

|---|---|---|

| CERVICAL RADICULOPATHY | ||

| C5 | Deltoid, biceps | Lateral upper arm |

| C6 | Biceps, brachioradialis | Radial forearm and first and second digits |

| C7 | Wrist extensors, triceps | Third and fourth digits |

| C8 | Intrinsic hand muscles | Fifth digit and ulnar forearm |

| T1 | Intrinsic muscles of the hand, especially APB | Axilla |

| LUMBAR RADICULOPATHY | ||

| L2 | Psoas, quadriceps | Lateral and anterior thigh |

| L3 | Psoas, quadriceps | Lower medial thigh |

| L4 | Tibialis anterior, quadriceps | Medial lower leg |

| L5 | Peroneus longus, gluteus medius, tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus | Lateral lower leg |

| S1 | Gastrocnemius, gluteus maximus | Lateral foot and fourth and fifth digits |

APB, Abductor pollicis brevis.

Diagnosis of radiculopathy can be facilitated by EMG, which is an aid to localization and helps determine whether acute changes are developing. MRI shows the structural cause of a definite radiculopathy in most patients, although the diagnostic yield in patients with back pain without clear radicular symptoms is far less (see Chapters 29 and 30). Many surgeons still consider myelography followed by CT scanning to be more sensitive than MRI for detecting structural defects, although it is not performed as a first-line investigation because of the invasive nature of the procedure.

Plexopathies

Pitfalls in the Differential Diagnosis for Hemiplegia and Monoplegia

Focal Weakness of Apparently Central Origin

Focal Weakness That Appears to Be Central: Cerebral Cortex, Internal Capsule, Brainstem, or Spinal Cord?

Weakness of the Hand and Wrist

Weakness in Intrinsic Muscles of the Hand: Median Nerve, Ulnar Nerve, Brachial Plexus, or Small Cerebral Cortical Lesion?

Leg Weakness

Cauda Equina Lesion, Myelopathy, or Paramedian Cerebral Cortical Lesion?

This chapter discusses monoplegia rather than paraplegia (see Chapter 24), but with leg weakness, it is important to differentiate between lower spinal cord dysfunction and cauda equina compression, between upper spinal cord involvement and cervical spondylotic myelopathy, and between these problems and midline cerebral lesions producing leg weakness.

Bowel and bladder incontinence can develop with all three locations but is more common with cauda equina lesions.

Bowel and bladder incontinence can develop with all three locations but is more common with cauda equina lesions.

Cauda equina lesions are associated with depressed reflexes, whereas spinal cord and cerebral lesions are characterized by hyperactive reflexes and upgoing plantar responses.

Cauda equina lesions are associated with depressed reflexes, whereas spinal cord and cerebral lesions are characterized by hyperactive reflexes and upgoing plantar responses.

Sensory loss is more prominent with cauda equina lesions than with higher lesions.

Sensory loss is more prominent with cauda equina lesions than with higher lesions.

Pain in the spine is approximately at the level of the lesion, although the localization is not exact.

Pain in the spine is approximately at the level of the lesion, although the localization is not exact.

Black D.F. Sporadic and familial hemiplegic migraine: diagnosis and treatment. Semin Neurol. 2006;26:208-216.

Chance P.F. Inherited focal, episodic neuropathies: hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies and hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8:159-174.

Freeman J.L., Coleman L.T., Smith L.J., et al. Hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia-epilepsy syndrome: characteristic early magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Child Neurol. 2002;17:10-16.

Lastilla M. Lacunar Infarct. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2006;28:205-215.

Marciniak C., Armon C., Wilson J., et al. Practice parameter: utility of electrodiagnostic techniques in evaluating patients with suspected peroneal neuropathy: an evidence-based review. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:520-527.

Misulis K.E. Essentials of Clinical Neurophysiology, third ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2003.

Misulis K.E., Head T.C. Netter’s Concise Neurology. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007.

Paciaroni M., Caso V., Milia P., et al. Isolated monoparesis following stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:805-807.

Shedid D., Benzel E.C. Cervical spondylosis anatomy: pathophysiology and biomechanics. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:S7-S13.

Wingerchuk D.M. The clinical course of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neurol Res. 2006;28:341-347.

Zhang Y.H., Sun W.X., Qin J., et al. Clinical characteristics of alternating hemiplegia of childhood in 13 patients. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2003;41:680-683.