Chapter 22 HEMATURIA, GROSS

General Discussion

The approach to gross hematuria begins with a description of the urine and questions directed toward associated symptoms. Recent illnesses, medication use, and family history also may provide important clues to the diagnosis. Discussion of each of the causes of hematuria is beyond the scope of this chapter but can be found in Meyers.4

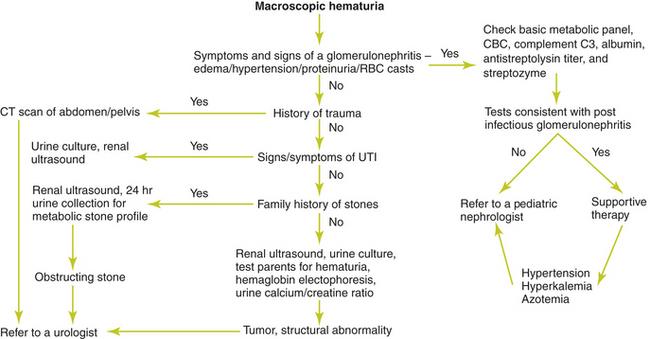

An algorithm for the approach to gross hematuria is provided below, (Figure 22-1) in addition to selected tests that may be used in the evaluation.

Medications Associated with Hematuria

Medications That May Cause Urinary Discoloration Misinterpreted as Hematuria

Causes of Hematuria

• Acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis

• Idiopathic hypercalciuria without urolithiasis

• Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

• Mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis

• Microangiopathic polyarteritis nodosa

• Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis

• Systemic lupus erythematosus

• Thin basement membrane disease (benign familial hematuria)

Key Historical Features

Key Physical Findings

Vital signs, especially elevated blood pressure or fever

Vital signs, especially elevated blood pressure or fever

General appearance, especially for pallor

General appearance, especially for pallor

Abdominal examination for abdominal or flank masses

Abdominal examination for abdominal or flank masses

Abdominal auscultation for bruits

Abdominal auscultation for bruits

Back examination for costovertebral angle tenderness

Back examination for costovertebral angle tenderness

Extremity examination for musculoskeletal findings such as arthritis

Extremity examination for musculoskeletal findings such as arthritis

Suggested Work-up

| Urine dipstick | Greater than 2+ proteinuria should raise suspicion for glomerular disease |

| Urine microscopy | To confirm the presence of RBCs |

| Red cell casts may be a clue to glomerulonephritis | |

| Bacteria and significant pyuria may indicate pyelonephritis or cystitis | |

| Renal ultrasound | Indicated for all children with macroscopic hematuria to evaluate for urologic disease, congenital abnormalities, or renal parenchymal disease |

| Electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, complement C3, albumin, anti streptolysin o titer, and streptozyme | Indicated for symptoms and signs of glomerulonephritis such as edema, complete blood cell count (CBC), hypertension, proteinuria, or RBC casts |

Additional Work-up

| CBC, BUN, and creatinine | If glomerulonephritis is suspected |

| C3, C4, antinuclear antibody, and anti-double-stranded DNA antibody | If systemic lupus erythematosus is suspected |

| C3, C4, antistreptolysin O, and anti-Dnase B antibody | If poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis is suspected |

| Antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody titer (ANCA) | If Wegener’s granulomatosis is suspected |

| Antiglomerular basement antibody titer | If Goodpasture’s syndrome is suspected |

| Skin biopsy | If Henoch-Schönlein purpura is suspected by the presence of arthralgias, purpura, pedal edema, abdominal pain, and hematochezia |

| 24-hour urine collection for protein or a spot urine protein-creatinine ratio | If proteinuria is present |

| Urine culture | Indicated in patients who have fever, flank pain, abdominal pain, or bladder pain |

| 24-hour urine collection for calcium or a spot urine calcium-creatinine ratio | If hypercalciuria is suspected. Hypercalciuria is defined as calcium excretion >4 mg/kg per day or a spot urine calcium-creatinine ratio of >0.22. Note that normal values may be greater in children younger than 7 years |

| Serum IgA | If IgA nephropathy is suspected |

| Urine eosinophils | If acute interstitial nephritis is suspected |

| Renal ultrasonography | If urologic disease or congenital abnormalities are suspected |

| Computed tomography (CT) imaging | May be used to identify kidney stones and provides detailed images of the bladder, pelvis, and retroperitoneum when looking for masses. Indicated promptly if there is a history of abdominal trauma. |

| Renal biopsy | If the diagnosis remains in doubt after laboratory and radiologic evaluation |

| Urology referral | Required when the clinical evaluation and work-up indicate a tumor, a structural urogenital abnormality, or an obstructing calculus. Referral is also indicated for recurrent nonglomerular macroscopic hematuria of undetermined origin because cystoscopy may be warranted |

1. Gordon C., Stapleton F.B. Hematuria in adolescents. Adolesc Med. 2005;16:229–239.

2. Ingelfinger J.R., Davis A.E., Grupe W.E. Frequency and etiology of gross hematuria in a general pediatric setting. Pediatrics. 1977;59:557–561.

3. Mahan J.D., Turman M.A., Mentser M.I. Evaluation of hematuria, proteinuria, and hypertension in adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44:1573–1589.

4. Meyers K.E.C. Evaluation of hematuria in children. Urol Clin North Am. 2004;31:559–573.

5. Pan C.G. Evaluation of gross hematuria. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:401–412.

6. Patel H.P., Bissler J.J. Hematuria in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:1519–1537.