113 Hematuria

• Hematuria can be a transient and incidental finding, or it can be caused by underlying and otherwise silent life-threatening disease.

• Infection is the most common cause of symptomatic hematuria in all age groups. Crystalluria and glomerulonephritis are more common in children; malignancy and nephrolithiasis are more common in adults.

• Patients with microscopic hematuria should have urinalysis repeated with their primary care provider about 1 week after discharge from the emergency department.

• All patients with gross hematuria warrant careful evaluation to ensure adequate urinary drainage. Those with difficulty passing clots, evidence of retention, or poor mobility should have a three-way Foley catheter placed in the emergency department.

• Although hematuria alone is rarely grounds for admission, emergency associated disease processes should be considered and excluded. Such processes include urosepsis, obstructing ureteral stone, renal parenchymal disease, coagulopathy, symptomatic anemia, intraabdominal injury in the setting of trauma, renal vein thrombosis, and aortic abdominal aneurysm.

Scope and Definitions

Gross (macroscopic) hematuria, visualized as red-colored urine, is disconcerting to most patients, but it does not always imply significant blood loss: as little as 1 mL of blood may turn 1 L of urine red. Dysuria is common in patients with gross hematuria, and urinary retention may develop if high-volume bleeding leads to clots that obstruct urethral outflow.1

Microscopic hematuria refers to the detection of more than three RBCs per high-power field (HPF) in a spun sample of urine sediment not visible to the naked eye.1,2 Screening of asymptomatic individuals suggests that up to 10% of adults and 6% of children may have some degree of microscopic hematuria at any given time.2–4 Typically an incidental and transient discovery, it can be associated with dysuria or pain. Because microscopic hematuria may be the only clue to previously undiagnosed structural, neoplastic, or inflammatory conditions, follow-up is essential.2–5

Pigmenturia (pseudohematuria) refers to urine that appears red or dark without RBCs detected by urine microscopy. A urine dipstick may register a positive test result for blood if hemoglobin, myoglobin, or bilirubin is present in the urine, as in the case of hemolysis, rhabdomyolysis, or jaundice. Pigmented urine with a negative dipstick test result may be caused by certain foods or medications (Table 113.1).

| DIAGNOSTIC CLUES | POSSIBLE DIAGNOSIS (NONGLOMULAR CAUSES) | POSSIBLE DIAGNOSIS (GLOMULAR CAUSES) |

|---|---|---|

| Hematuria in the Adult and Pediatric Patient | ||

| Trauma (blunt or penetrating) | Renal or bladder injury, at risk for other intraabdominal injuries | |

| Suprapubic pain or lower tract symptoms (dysuria, urgency, frequency, suprapubic pain) | UTI | |

| Flank pain | Stones, pyelonephritis, renal vein thrombosis, renal cyst, renal arteriovenous malformation | IgA nephropathy, glomerulonephritis |

| Hypercoagulable state and acute-onset flank pain | Renal vein thrombosis | |

| Elevated blood pressure | Glomerulonephritis | |

| Risk factors for muscle injury; viremia, exertion, crush injury, sympathomimetic drug use | Rhabdomyolysis | |

| Cough, hemoptysis | Vasculitis | |

| Sickle cell disease | Papillary necrosis | Glomerulonephritis |

| Cancer treatment | Radiation- or cyclophosphamide-associated cystitis | |

| Travel history | Schistosomiasis, tuberculosis | |

| Coagulopathy (hemophilia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura) or anticoagulation | Bleeding diathesis | |

| Pregnancy | Preeclampsia | |

| Diet: beets, berries, rhubarb Medications: quinine sulfate, phenazopyridine, rifampin, phenytoin |

Pseudohematuria (pigmenturia) | |

| Nail or patellar abnormalities | Nail-patella syndrome | |

| Hematuria in the Pediatric Patient | ||

| Recent illness (pharyngitis, impetigo, viral illness) | Postinfectious glomerulonephritis | |

| Abdominal pain | UTI, hypercalciuria, stone | HSP |

| Concurrent illness | IgA nephropathy | |

| Arthralgias | HSP, SLE | |

| Diarrhea (± bloody) | HUS | |

| Hearing loss | Alport syndrome | |

| Family history of hematuria or kidney disease | Polycystic kidney disease, hypercalciuria | Benign familial hematuria, thin basement disease, Alport syndrome |

| Rash (purpura, petechiae) | Bleeding dyscrasia, abuse | HSP, SLE, HUS |

| Edema | Glomerulonephritis, nephrotic syndrome | |

| Abdominal mass | Wilms tumor, hydronephrosis, polycystic kidney disease | |

| Conjunctivitis, pharyngitis | Adenovirus (hemorrhagic cystitis) | |

| Meatal erythema or stenosis | Masturbation, infection, trauma | |

| Hematuria in the Adult Patient | ||

| Age > 40, smoking history, analgesic abuse, Schistosoma exposure, pelvic irradiation, exposure to chemicals | Urogenital tract cancer | |

| Flank pain | Angiomyolipoma, AAA | |

| Pulsatile abdominal mass | AAA | |

| Atrial fibrillation | Anticoagulation (warfarin), renal emboli | |

| New heart murmur, fever | Renal emboli from endocarditis | |

| Dribbling with urination, urinary retention | Benign prostatic hypertrophy | |

| Dysuria, discharge | Urethritis, sexually transmitted disease | |

| Dysuria, frequency, perineal pain | Prostatitis | |

| Scrotal pain | Epididymitis | |

| Cyclic hematuria during menstrual pain | Endometriosis | |

| NSAID use, diabetes, sickle cell disease | Papillary necrosis | |

AAA, Abdominal aortic aneurysm; HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Pathophysiology

Hematuria results from the admixture of blood and urine as a result of infection, inflammation, or injury at any point along the genitourinary tract. Causes of hematuria can be divided into glomerular and nonglomerular (see Table 113.1). Glomerular causes, such as glomerulonephritis, are more common in children than in adults and are frequently associated with systemic medical illness. Nonglomerular causes of hematuria can be further classified as renal (e.g., papillary necrosis), extrarenal (e.g., bladder cancer), traumatic (e.g., renal contusion), coagulopathy related (e.g., patient taking warfarin), and factitious (e.g., Munchausen syndrome).

Minor trauma caused by high-impact exercise, such as long-distance running, can produce transient microscopic hematuria.5,6 Persistent or high-volume bleeding is generally pathologic and mandates further evaluation.

Differential Diagnosis

Hematuria may be a sign of a large number of diseases (see Table 113.1).1–9 Infection at any location in the genitourinary tract can cause hematuria and is the most common cause of hematuria in both adults and children.

Nephrolithiasis is the second most common cause of hematuria in adults (see Chapter 112). Microscopic hematuria is a common finding in patients with suspected ureteral colic and is caused by abrasion of mucosal tissue by the stone; however, hematuria may be absent in patients with complete ureteral obstruction.6 Thus, exclusion of the diagnosis of a ureteral stone should not be based solely on negative findings on urinalysis. Although nephrolithiasis is not as common in children, it must remain part of the differential diagnosis. Hypercalciuria is often associated with recurrent asymptomatic microscopic hematuria, and affected children may face higher risk than their peers for the development of nephrolithiasis.2,7

Glomerulonephritis, responsible for 10% of cases of gross pediatric hematuria, is usually accompanied by systemic symptoms such as hypertension.8 Systemic lupus erythematosus and other chronic inflammatory disorders can also cause hematuria by similar mechanisms.2,5,6,8

The family history may provide a clue to glomerulonephritis and other disorders associated with hematuria that are due to rare genetic causes (see Table 113.1).2,5,6,8

A particularly common cause of pigmenturia in newborns is urate crystals, which result from poor oral intake and decreased urine output (Fig. 113.1).2,8 Discovery of these crystals in the diaper should prompt evaluation for dehydration with no further work-up for hematuria. Pigmenturia can also be due to a medication side effect and usually has no clinical significance (see Table 113.1).

Fig. 113.1 Urate crystals, a common finding in the diaper of a newborn.

(Courtesy Janelle Aby, MD, Newborn Nursery, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford University.)

Anticoagulant use may be associated with varying degrees of hematuria, yet serious underlying causes such as malignancy should not be excluded without further investigation or close follow-up.1,6,9 It is important to understand that painless hematuria, whether transient or persistent, may be the only symptom of a malignancy, which accounts for 10% to 20% of underlying causes of hematuria in adults.3,9

Diagnostic Testing

The point-of-care urine dipstick test can detect the equivalent of 1 to 2 RBCs/HPF. False-positive results can occur with myoglobinuria and hemoglobinuria.5,6 If a urine dipstick test is positive for the detection of blood, standard urinalysis should be performed. Urinalysis is highly sensitive and specific; however, it is more expensive and time intensive than the urine dipstick test. Urinalysis quantifies the amount of blood present and can differentiate the presence of myoglobin or hemoglobin.5 Thus in the appropriate context, patients with a urine dipstick positive for blood and negative findings on urinalysis should be evaluated for rhabdomyolysis, hemolysis, or hyperbilirubinemia.

The presence of casts, dysmorphic RBCs, and proteinuria is associated with glomerular causes of hematuria (Table 113.2).

| FACTOR | GLOMERULAR | NONGLOMERULAR |

|---|---|---|

| Color | Smoky, tea or cola colored, red | Red or pink |

| RBC morphology | Dysmorphic | Normal |

| Casts | RBC, WBC | None |

| Clots | Absent | Present (±) |

| Proteinuria | ≥2+ | <2+ |

RBC, Red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell

Reproduced from Massengill S. Hematuria. Pediatr Rev 2008;29:342-7.

Incidental microscopic hematuria without associated symptoms or hemodynamic instability mandates confirmation of normal blood pressure in pediatric patients as a screen for glomerulonephritis, obstructive uropathy, or other systemic disease.2,8 Normotensive patients require no further testing in the emergency department (ED), but all patients will need follow-up evaluation as an outpatient.2,5,6,8

Urine culture should be considered in the setting of suspected infection, especially in pediatric patients or those with indwelling Foley catheters. Urine calcium and creatinine determination is useful in a child with hematuria who does not have a urinary tract infection or a glomerular cause to confirm the diagnosis of hypercalciuria (urine calcium-creatinine ratio > 0.2).2,7,8 Urine cytology for malignancy has poor sensitivity in the ED setting and should not be ordered as part of the ED evaluation.1

In patients with gross hematuria or symptomatic microscopic hematuria, blood should be sent for a complete blood cell count and renal function testing (blood urea nitrogen, creatinine). A coagulation panel should be ordered for patients who are taking anticoagulants or have a suspected or known coagulopathy.1 Patients with unstable vital signs, heavy bleeding, and symptomatic anemia should have blood typed and screened for a potential transfusion.

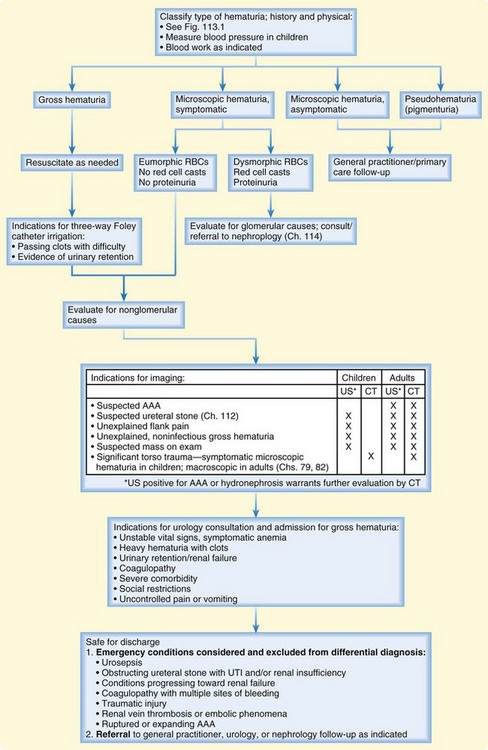

Although hematuria associated with flank pain may suggest a ureteral stone, a rupturing abdominal aortic aneurysm or renal vein thrombosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis (see Table 113.1).6 For this reason, imaging can be used to exclude these emergency diagnoses when clinically indicated (Fig. 113.2).1,6 Ultrasonography is useful for the evaluation of microscopic hematuria in children and as a screen for obstruction, hydronephrosis, and abdominal aortic aneursym.1,2,6 It less expensive than computed tomography (CT) and is safer because of lack of radiation and intravenous contrast agents. Non–contrast-enhanced CT may be used to indentify the size and location of renal stones. Contrast-enhanced CT is more sensitive than ultrasound for the detection of small renal masses. Contrast-enhanced CT is necessary to elucidate the integrity of intraabdominal and retroperitoneal structures in the setting of significant trauma associated with hematuria.3,4,10–12

In pediatric victims of significant blunt thoracoabdominal trauma, microscopic hematuria consisting of more than 5 RBCs/HPF indicates the need for further evaluation with abdominal and pelvic CT.10 For pediatric trauma patients who are not toilet-trained, bag urine collection may be preferred over catheterization as a screen for hematuria because the trauma from catheterization can lead to false-positive urine specimens.

In adults with blunt trauma, a higher cutoff (>50 RBCs/HPF) for microscopic hematuria is associated with increased risk for intraabdominal injury worthwhile of abdominal and pelvic CT.11 As a screen for bladder injury, gross hematuria has greater sensitivity and specificity than microscopic hematuria does.12

Treatment and Disposition

Treatment varies depending on the underlying diagnosis and degree of hematuria (see Fig. 113.2). Intravenous fluids, analgesics, and antiemetics may be needed in patients with gross hematuria.

Patients with gross hematuria who are able to void should be asked about the presence of clots in their urinary flow and the ease with which they are passed. Foley catheterization may be avoided in stable, sensible, and mobile patients who are able to void easily and who have a few small clots that pass with ease. If clot retention or significant dysuria is present, the treatment of choice is insertion of a three-way Foley catheter to facilitate irrigation of the bladder to dislodge clots and allow bladder decompression.1 Saline should be irrigated continuously through the third port until the urine turns pink to clear and is free of clots. In the setting of trauma, urethral injury should be excluded before catheter placement (see Chapter 82). Stable patients with improved symptoms may be discharged with a leg bag and instructions for urology follow-up in 3 to 5 days.

Consultation with a nephrologist may be helpful in cases of suspected glomerular disease or obstructive uropathy in a child. Urology consultation should be obtained for patients with malignancies and for patients with high-volume, noninfectious gross hematuria. Hematuria alone is rarely an indication for admission, except as noted in Figure 113.2.1,6

The vast majority of patients with hematuria are discharged with further care as an outpatient. Incidental cases require repeated urinalysis in 1 week.1,4,6 Patients treated for gross hematuria should be instructed to drink plenty of fluids and return if they have an inability to void, fever, pain, worsening dysuria, and gross hematuria that fails to clear.

1 Hicks D, Li C. Management of macroscopic hematuria in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:385–390.

2 Massengill S. Hematuria. Pediatr Rev. 2008;29:342–347.

3 Khadra M, Pickard R, Charlton M, et al. A prospective analysis of 1,930 patients with hematuria to evaluate current diagnostic practice. J Urol. 2001;163:524–527.

4 Tu W, Shortliffe L. Evaluation of asymptomatic, atraumatic hematuria in children and adults. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:189–194.

5 Cohen R, Brown R. Microscopic hematuria. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2330–2338.

6 Sokolosky M. Hematuria. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19:621–632.

7 Feld L, Meyers K, Kaplan B, et al. Limited evaluation of microscopic hematuria in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1998;102:E42.

8 Davis I, Avner E. Clinical evaluation of the child with hematuria. In: Kleigman R, Behrman R, Jenson H, et al. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. Philadelphia: Saunders; 18th ed. 2007:2170–2173.

9 Mariani A, Mariani M, Macchioni C, et al. The significance of adult hematuria: 1,000 hematuria evaluations including a risk-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis. J Urol. 1989;141:350–355.

10 Holmes J, Mao A, Awasthi S, et al. Validation of a prediction rule for the identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries after blunt torso trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:528–533.

11 Holmes J, Wisner D, McGahan J, et al. Clinical prediction rules for identifying adults at very low risk for intra-abdominal injuries after blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:575–584.

12 Brewer M, Wilmoth R, Enderson B, et al. Prospective comparison of microscopic and gross hematuria as predictors of bladder injury in blunt trauma. Urology. 2007;69:1086–1089.