Chapter 68 Hematologic Manifestations of Childhood Illness

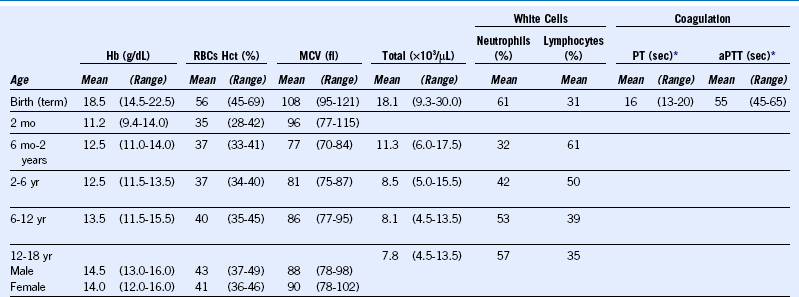

Table 68-1 Normal Hematologic Values in Childhood

aPTT, Activated partial thromboplastin time; Hb, hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; PT, prothrombin time; RBC, red blood cell.

Data from Rudolph AM, Hoffman JIE, eds: Pediatrics, ed 17, East Norwalk, Conn, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1982, p 1036, and from Nathan DG, Oski FA, eds: Hematology of infancy and childhood, ed 3, Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1987, p 1679.

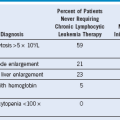

Table 68-2 Preliminary Diagnostic Guidelines for Macrophage Activation Syndrome in Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis*

| Laboratory Criteria |

|---|

| Clinical Criteria |

| Histopathologic Criterion |

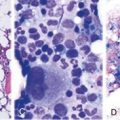

| Evidence of macrophage hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow aspirate |

| Diagnostic Rule |

| The diagnosis of MAS requires the presence of any two or more laboratory criteria or of ≥2 clinical or laboratory criteria. A bone marrow aspirate for the demonstration of hemophagocytosis may be required only in doubtful cases. |

MAS, Macrophage activation syndrome.

*The suggested criteria are useful only in patients with active systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The laboratory thresholds are examples only and are not specific for the diagnosis.

From Ravelli A, Magni-Manzoni S, Pistorio A, et al: Preliminary diagnostic guidelines for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr 146:598, 2005.

How to Manage Thromboembolism in the Setting of Pediatric Cancer

When treating thromboembolism in a patient with cancer, LMWH is the preferred choice. Warfarin, although it is less expensive and can be given orally, is difficult to regulate in the setting of multiple chemotherapy agents, frequent invasive procedures, and changing vitamin K stores because of antibiotics and illness.1–3 A randomized clinical trial in adult cancer patients demonstrated that LMWH was more efficacious and as safe as warfarin in preventing recurrent thromboembolism.4 The 2008 ACCP guidelines recommend the use of LMWH in the treatment of cancer-related venous thromboembolism for a minimum of 3 months and until the precipitating factor (e.g., use of asparaginase) has resolved.222 Other practical suggestions have been reported, but none are supported by any systematic observations.2,5,6

• A minimum of two doses of LMWH should be held before lumbar punctures and other invasive procedures.

• For intramuscular asparaginase injections, applying firm pressure and administering the medication at the trough of the anti-Xa level are probably adequate to avoid bleeding.

• Clinicians should maintain platelet counts above 50,000/µL in the first 2 weeks of anticoagulation. After that time period, the LMWH dose should be adjusted according to platelet count (50% dosing for platelet counts 20-50,000/µL; hold doses for platelet counts <20,000/µL).

Asparaginase-Related Thrombosis

• Asparaginase can be resumed when symptoms of thrombosis have resolved and there is evidence of clot stabilization or improvement on repeat imaging, typically after about 4 weeks of anticoagulation.

• Because of the protein depletion experienced by patients receiving asparaginase, anti-Xa levels should be monitored frequently.

• If LMWH at previously adequate doses no longer adequately anticoagulates the patient, antithrombin levels should be checked and antithrombin repleted as necessary.

Treatment of Immune-Mediated Thrombocytopenia After Solid Organ Transplantation in Children

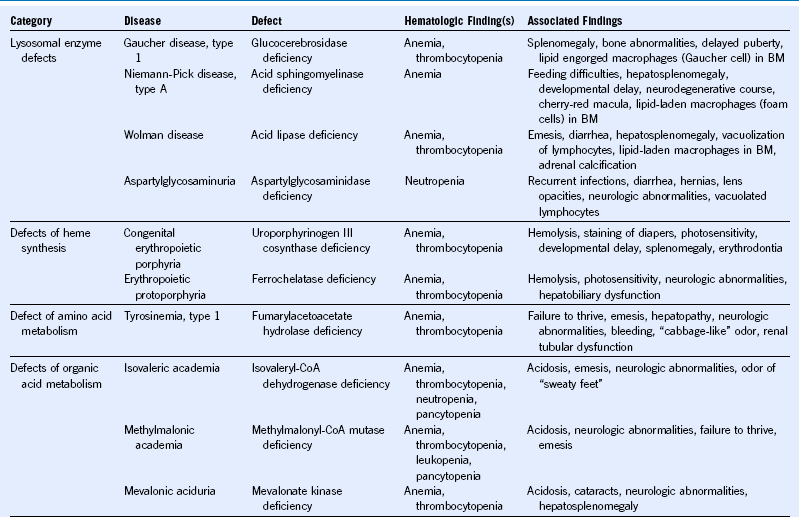

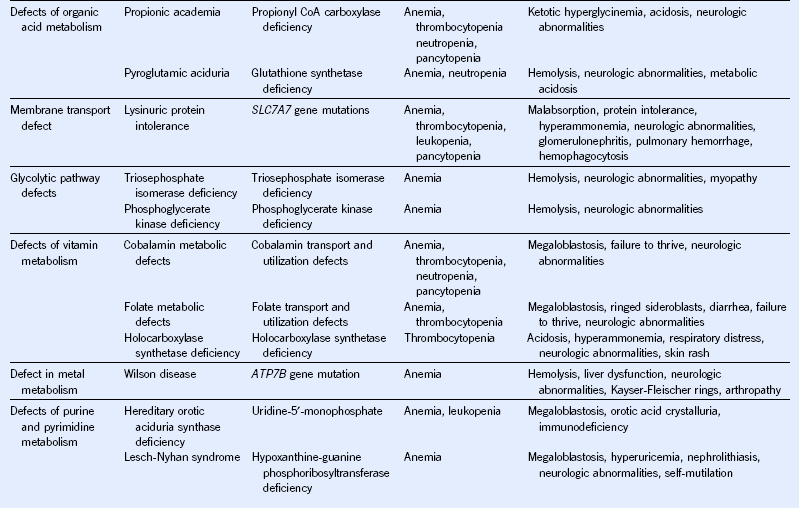

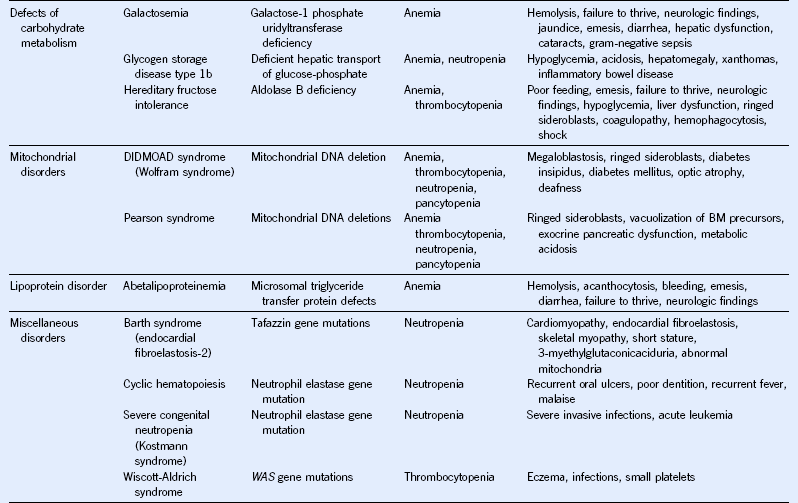

Table 68-3 Hematologic Manifestations of Metabolic Disease With Onset in Infancy and Childhood

BM, Bone marrow; CoA, coenzyme A; DIDMOAD, diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, deafness.

Evaluation and Management of Children With Splenomegaly

When evaluating a child with chronic splenomegaly, the clinician must consider all of the possibilities noted in Table 68-4. Clues from the history and physical examination may suggest a specific etiology and direct a tailored approach to the diagnostic laboratory evaluation. If, on the other hand, there is no apparent cause of the enlarged spleen, a number of screening laboratory tests should be performed, including a complete blood count with differential, platelet count, and reticulocyte count; evaluation of the peripheral smear; determination of sedimentation rate; liver function tests; determination of antibody titers to EBV, CMV, and Toxoplasma spp.; antinuclear antibody assay; and ultrasound evaluation of the liver, spleen, and portal system (the last with Doppler flow technique). Further evaluation, including bone marrow examination, may be necessary if the screening tests do not reveal the cause of the splenic enlargement.

For children younger than 5 years of age with severe symptoms from hemolytic anemia, hemoglobinopathy, or hypersplenism, partial splenectomy should be considered. In a number of studies, up to 90% of the spleen has been removed safely, with a high rate of success and preservation of splenic function.7,8 Regrowth of the spleen to variable degrees has been noted, with occasional need for reoperation.

| DISORDERS OF THE BLOOD |

CMV, Cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; TORCH, toxoplasmosis, other infections, rubella, cytomegalovirus infection, herpes simplex.

1 Massicotte P, Julian JA, Gent M, et al. An open label randomized controlled trial of low molecular weight heparin for the prevention of central venous line related thrombotic complications in children: the PROTEKT trial. Thrombosis Research. 2003;109:101.

2 Bajzar L, Chan AK, Massicotte MP, et al. Thrombosis in children with malignancy. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:1.

3 Wiernikowski JT, Athale UH. Thromboembolic complications in children with cancer. Thromb Res. 2006;118:137.

4 Lee AYY, Levine M, Baker RI, et al. Low molecular weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:146.

5 Athale U, Cox S, Siciliano S, et al. Thromboembolism in children with sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:171.

6 Monagle P, Chalmers E, Chan A, et al. American College of Chest Physicians: Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice guidelines, ed 8. Chest. 2008;133:887S.

7 Bader-Meunier B, Gauthier F, Archambaud F, et al. Long-term evaluation of the beneficial effect of subtotal splenectomy for management of hereditary spherocytosis. Blood. 2001;97:399.

8 Rice HE, Oldham KT, Hillery CA, et al. Clinical and hematologic benefits of partial splenectomy for congenital hemolytic anemias in children. Ann Surg. 2003;237:281.