Chapter 681 Heat Injuries

Heat illness is the 3rd leading cause of death in U.S. high school athletes. It is a continuum of clinical signs and symptoms that can be mild (heat stress) to fatal (heatstroke) (Chapter 64). Children are more vulnerable to heat illness than adults. They have greater ratio of surface area to body mass than adults and produce greater heat per kilogram of body weight than adults during activity. The sweat rate is lower in children and the temperature at which sweating occurs is higher. Children can take longer to acclimatize to warmer, more humid environments (typically 8-12 near-consecutive days of 30-45 min exposures). Children also have a blunted thirst response compared to adults and might not consume enough fluid during exercise to prevent dehydration.

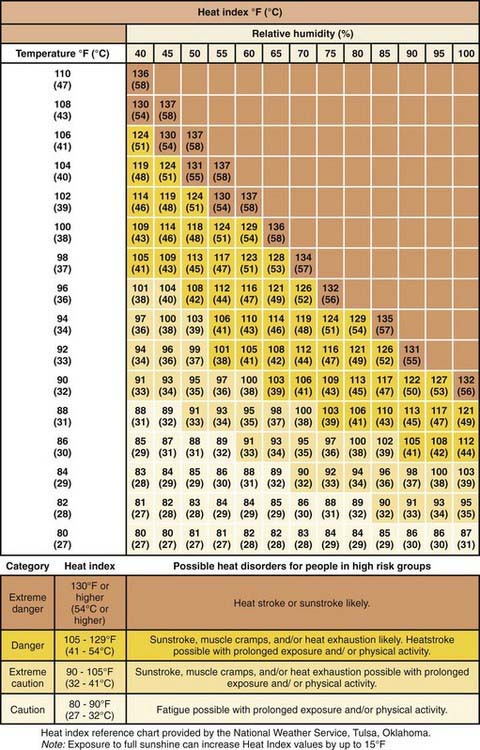

Dehydration is common to all heat illness; therefore, measures to prevent dehydration can also prevent heat illness. Thirst is not an adequate indicator of hydration status because it is initiated at 2-3% dehydration. Athletes are advised to be well hydrated before exercise and should drink every 20 min during exercise (5 oz for those weighing 40 kg, 9 oz for 60 kg, and 10-12 oz for those >60 kg). Free access to cold water should be advocated to coaches. During a football practice, scheduled breaks every 20-30 min with helmets off to get out of the heat can decrease the cumulative amount of heat exposure. Practices and competition should be scheduled in the early morning or late afternoon to avoid the hottest part of the day. Guidelines have been published about modifying activity related to temperature and humidity (Fig. 681-1). Proper clothing such as shorts and t-shirts without helmets can improve heat dissipation. Prepractice and postpractice weight can be helpful in determining the amount of fluid necessary to replace (8 oz for each pound of weight loss).

Figure 681-1 Heat stroke index.

(From Jardine DS: Heat illness and heat stroke, Pediatr Rev 28:249–258, 2007.)

Almond CSD, Shin AY, Fortescue EB. Hyponatremia among runners in the Boston marathon. N Engl J Med. 2005;15:1150-1156.

2000 American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness: Climatic heat stress and the exercising child and adolescent. Pediatrics. 2000;106:158-159.

Bytomski JR, Squire DL. Heat illness in children. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2003;2:320-324.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heat illness among high school athletes—United States, 2005-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1009-1013.

Jardine DS. Heat illness and heat stroke. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28:249-258.