Chapter 2

Heart Murmurs

1. What are the auscultatory areas of murmurs?

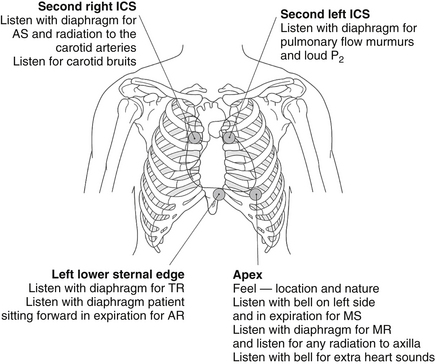

Auscultation typically starts in the aortic area, continuing in clockwise fashion: first over the pulmonic, then the mitral (or apical), and finally the tricuspid areas (Fig. 2-1). Because murmurs may radiate widely, they often become audible in areas outside those historically assigned to them. Hence, “inching” the stethoscope (i.e., slowly dragging it from site to site) can be the best way to avoid missing important findings.

Figure 2-1 Sequence of auscultation of the heart. AR, Aortic regurgitation; AS, aortic stenosis; ICS, intercostal space; MR, mitral regurgitation; MS, mitral stenosis; TR, tricuspid regurgitation. (From Baliga R: Crash course cardiology, St Louis, 2005, Mosby.)

2. What is the Levine system for grading the intensity of murmurs?

1/6: a murmur so soft as to be heard only intermittently, never immediately, and always with concentration and effort

1/6: a murmur so soft as to be heard only intermittently, never immediately, and always with concentration and effort

2/6: a murmur that is soft but nonetheless audible immediately and on every beat

2/6: a murmur that is soft but nonetheless audible immediately and on every beat

3/6: a murmur that is easily audible and relatively loud

3/6: a murmur that is easily audible and relatively loud

4/6: a murmur that is relatively loud and associated with a palpable thrill (always pathologic)

4/6: a murmur that is relatively loud and associated with a palpable thrill (always pathologic)

5/6: a murmur loud enough that it can be heard even by placing the edge of the stethoscope’s diaphragm over the patient’s chest

5/6: a murmur loud enough that it can be heard even by placing the edge of the stethoscope’s diaphragm over the patient’s chest

6/6: a murmur so loud that it can be heard even when the stethoscope is not in contact with the chest, but held slightly above its surface

6/6: a murmur so loud that it can be heard even when the stethoscope is not in contact with the chest, but held slightly above its surface

3. What are the causes of a systolic murmur?

Ejection: increased “forward” flow over the aortic or pulmonic valve. This can be:

Ejection: increased “forward” flow over the aortic or pulmonic valve. This can be:

Physiologic: normal valve, but flow high enough to cause turbulence (anemia, exercise, fever, and other hyperkinetic heart syndromes)

Physiologic: normal valve, but flow high enough to cause turbulence (anemia, exercise, fever, and other hyperkinetic heart syndromes)

Pathologic: abnormal valve, with or without outflow obstruction (i.e., aortic stenosis versus aortic sclerosis)

Pathologic: abnormal valve, with or without outflow obstruction (i.e., aortic stenosis versus aortic sclerosis)

Regurgitation: “backward” flow from a high- into a low-pressure bed. Although this is usually due to incompetent atrioventricular (AV) valves (mitral or tricuspid), it also can be due to ventricular septal defect.

Regurgitation: “backward” flow from a high- into a low-pressure bed. Although this is usually due to incompetent atrioventricular (AV) valves (mitral or tricuspid), it also can be due to ventricular septal defect.

4. What are functional murmurs?

5. What is the most common systolic ejection murmur of the elderly?

The murmur of aortic sclerosis is common in the elderly. This early peaking systolic murmur is extremely age related, affecting 21% to 26% of persons older than 65, and 55% to 75% of octogenarians. (Conversely, the prevalence of aortic stenosis [AS] in these age groups is 2% and 2.6%, respectively.) The murmur of aortic sclerosis may be due to either a degenerative change of the aortic valve or abnormalities of the aortic root. Senile degeneration of the aortic valve includes thickening, fibrosis, and occasionally calcification. This can stiffen the valve and yet not cause a transvalvular pressure gradient. In fact, commissural fusion is typically absent in aortic sclerosis. Abnormalities of the aortic root may be diffuse (such as a tortuous and dilated aorta) or localized (like a calcific spur or an atherosclerotic plaque that protrudes into the lumen, creating a turbulent bloodstream).

6. How can physical examination help differentiate functional from pathologic murmurs?

There are two golden and three silver rules:

The first golden rule is to always judge (systolic) murmurs like people: by the company they keep. Hence, murmurs that keep bad company (like symptoms; extra sounds; thrill; and abnormal arterial or venous pulse, electrocardiogram, or chest radiograph) should be considered pathologic until proven otherwise. These murmurs should receive extensive evaluation, including technology-based assessment.

The first golden rule is to always judge (systolic) murmurs like people: by the company they keep. Hence, murmurs that keep bad company (like symptoms; extra sounds; thrill; and abnormal arterial or venous pulse, electrocardiogram, or chest radiograph) should be considered pathologic until proven otherwise. These murmurs should receive extensive evaluation, including technology-based assessment.

The second golden rule is that a diminished or absent S2 usually indicates a poorly moving and abnormal semilunar (aortic or pulmonic) valve. This is the hallmark of pathology. As a flip side, functional systolic murmurs are always accompanied by a well-preserved S2, with normal split.

The second golden rule is that a diminished or absent S2 usually indicates a poorly moving and abnormal semilunar (aortic or pulmonic) valve. This is the hallmark of pathology. As a flip side, functional systolic murmurs are always accompanied by a well-preserved S2, with normal split.

Thus, functional murmurs should be systolic, short, soft (typically less than 3/6), early peaking (never passing mid-systole), predominantly circumscribed to the base, and associated with a well-preserved and normally split-second sound. They should have an otherwise normal cardiovascular examination and often disappear with sitting, standing, or straining (as, for example, following a Valsalva maneuver).

7. How much reduction in valvular area is necessary for the AS murmur to become audible?

8. What factors may suggest severe AS?

Murmur intensity and timing (the louder and later peaking the murmur, the worse the disease)

Murmur intensity and timing (the louder and later peaking the murmur, the worse the disease)

Delayed upstroke and reduced amplitude of the carotid pulse (pulsus parvus and tardus)

Delayed upstroke and reduced amplitude of the carotid pulse (pulsus parvus and tardus)

10. What is isometric hand grip, and what does it do to AS and mitral regurgitation (MR) murmurs?

11. What is the Gallavardin phenomenon?

A typical AS-like murmur (medium to low pitched, harsh, right parasternal, typically radiated to the neck, and caused by high-velocity jets into the ascending aorta)

A typical AS-like murmur (medium to low pitched, harsh, right parasternal, typically radiated to the neck, and caused by high-velocity jets into the ascending aorta)

A murmur that instead mimics MR (high pitched, musical, and best heard at the apex)

A murmur that instead mimics MR (high pitched, musical, and best heard at the apex)

12. Where is the murmur of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) best heard?

13. What are the characteristics of a ventricular septal defect (VSD) murmur?

14. What is a systolic regurgitant murmur?

One characterized by a pressure gradient that causes a retrograde blood flow across an abnormal opening. This can be (1) a ventricular septal defect, (2) an incompetent mitral valve, (3) an incompetent tricuspid valve, or (4) fistulous communication between a high-pressure and a low-pressure vascular bed (such as a patent ductus arteriosus).

15. What are the auscultatory characteristics of systolic regurgitant murmurs?

16. What are the characteristics of the MR murmur?

17. What are the characteristics of the acute MR murmur?

18. What are the characteristics of the mitral valve prolapse (MVP) murmur?

19. How are diastolic murmurs classified?

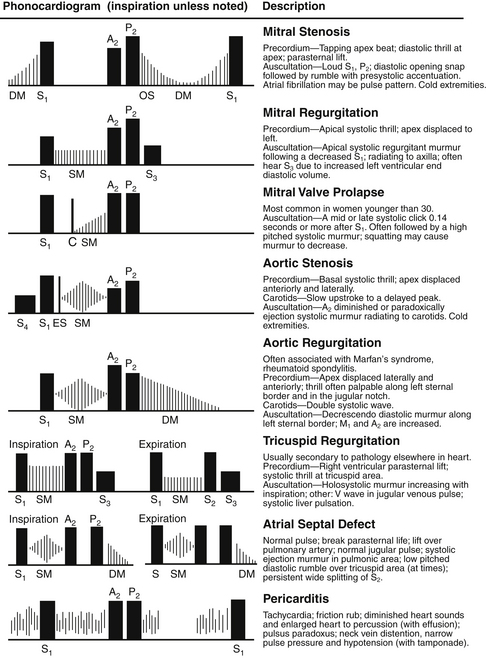

Diastolic murmurs are classified by their timing. Hence, the most important division is between murmurs that start just after S2 (i.e., early diastolic—reflecting aortic or pulmonic regurgitation) versus those that start a little later (i.e., mid to late diastolic, often with a presystolic accentuation—reflecting mitral or tricuspid valve stenosis) (Fig. 2-2).

Figure 2-2 Phonocardiographic description of pathologic cardiac murmurs. (From James EC, Corry RJ, Perry JF: Principles of basic surgical practice, Philadelphia, 1987, Hanley & Belfus.)

20. What is the best strategy to detect the mitral stenosis (MS) murmur?

21. What are the typical auscultatory findings of aortic regurgitation (AR)?

An accompanying systolic murmur may be due to concomitant AS but most commonly indicates severe regurgitation, followed by an increased systolic flow across the valve. Hence, this accompanying systolic murmur is often referred to as comitans (Latin for “companion”). It provides an important clue to the severity of regurgitation. A second diastolic murmur can be due to the rumbling diastolic murmur of Austin Flint (i.e., functional MS). The Austin Flint murmur is a mitral stenosis–like diastolic rumble, best heard at the apex, and results from the regurgitant aortic stream preventing full opening of the anterior mitral leaflet.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Blaufuss Medical Multimedia Laboratories. Heart sounds and cardiac arrhythmias, an excellent audiovisual tutorial on heart sounds. Available at http://www.blaufuss.org/. Accessed January 14, 2013

2. Constant, J., Lippschutz, E.J. Diagramming and grading heart sounds and murmurs. Am Heart J. 1965;70:326–332.

3. Danielsen, R., Nordrehaug, J.E., Vik-Mo, H. Clinical and haemodynamic features in relation to severity of aortic stenosis in adults. Eur Heart J. 1991;12:791–795.

4. Etchells, E., Bell, C., Robb, K. Does this patient have an abnormal systolic murmur? JAMA. 1997;277:564–571.

5. Mangione, S. Physical diagnosis secrets, ed 2. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2008.

6. University of Washington Department of Medicine. Examination for heart sounds and murmurs. Available at http://depts.washington.edu/physdx/heart/index.html. Accessed January 14, 2013