Chapter 51

Heart Disease in Pregnancy

1. What cardiac physiologic changes occur during pregnancy?

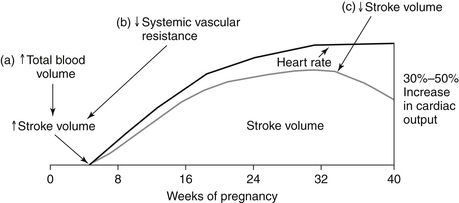

Hormonal changes cause an increase in both plasma volume (from water and sodium retention) and red blood cell volume (from erythrocytosis) during a normal pregnancy. A disproportionate increase in plasma volume explains the physiologic anemia of pregnancy. Maternal heart rate (HR) increases throughout the 40 weeks, mediated partially by increased sympathetic tone and heat production. Stroke volume subsequently continues to increase until the third trimester, when inferior vena cava (IVC) return may be compromised by the gravid uterus. Maternal cardiac output increases by 30% to 50% during a normal pregnancy. Systolic blood pressure drops during the first half of pregnancy and returns to normal levels by delivery. The physiologic changes related to cardiac output that occur during pregnancy are shown in Figure 51-1.

2. Are there independent vascular changes that occur during a normal pregnancy?

3. What are normal cardiac signs and symptoms of pregnancy?

Hyperventilation (as a result of increased minute ventilation)

Hyperventilation (as a result of increased minute ventilation)

Peripheral edema (from volume retention and vena caval compression by the gravid uterus)

Peripheral edema (from volume retention and vena caval compression by the gravid uterus)

Dizziness/lightheadedness (from reduced SVR and vena caval compression)

Dizziness/lightheadedness (from reduced SVR and vena caval compression)

4. What are pathologic cardiac signs and symptoms of pregnancy?

Anasarca (generalized edema) and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea are not components of normal pregnancy and warrant workup.

Anasarca (generalized edema) and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea are not components of normal pregnancy and warrant workup.

Syncope warrants evaluation for pulmonary embolism, tachy- or bradyarrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, obstructive valvular pathology (aortic, mitral, or pulmonic stenosis), or hypotension.

Syncope warrants evaluation for pulmonary embolism, tachy- or bradyarrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, obstructive valvular pathology (aortic, mitral, or pulmonic stenosis), or hypotension.

Chest pain may be due to aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, angina, or even myocardial infarction. As more women delay childbearing, there is a higher incidence of preexisting cardiac disease and risk factors in pregnant women.

Chest pain may be due to aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, angina, or even myocardial infarction. As more women delay childbearing, there is a higher incidence of preexisting cardiac disease and risk factors in pregnant women.

Hemoptysis may be a harbinger of occult mitral stenosis, although rheumatic heart disease is becoming less common in developed countries.

Hemoptysis may be a harbinger of occult mitral stenosis, although rheumatic heart disease is becoming less common in developed countries.

5. What are normal cardiac examination findings during pregnancy?

Blood pressure (BP) will decline and HR will increase.

Blood pressure (BP) will decline and HR will increase.

The point of maximum impulse will be displaced laterally as the uterus enlarges.

The point of maximum impulse will be displaced laterally as the uterus enlarges.

S3 heart sound is common because of increased rapid filling of the left ventricle (LV) in early diastole.

S3 heart sound is common because of increased rapid filling of the left ventricle (LV) in early diastole.

A physiologic pulmonic flow murmur is common because of elevated stroke volume passing through a normal valve.

A physiologic pulmonic flow murmur is common because of elevated stroke volume passing through a normal valve.

A mammary soufflé (due to increased blood flow into the breasts) and venous hum (due to increased blood flow through jugular veins) are two continuous, superficial murmurs that can be obliterated by compressing the site with the diaphragm of the stethoscope. If the murmur does not change, consider patent ductus arteriosus or coronary arteriovenous (AV) fistula.

A mammary soufflé (due to increased blood flow into the breasts) and venous hum (due to increased blood flow through jugular veins) are two continuous, superficial murmurs that can be obliterated by compressing the site with the diaphragm of the stethoscope. If the murmur does not change, consider patent ductus arteriosus or coronary arteriovenous (AV) fistula.

6. What are pathologic cardiac exam findings during pregnancy?

Clubbing and cyanosis are not a part of normal pregnancy; desaturation for any reason is abnormal and warrants investigation.

Clubbing and cyanosis are not a part of normal pregnancy; desaturation for any reason is abnormal and warrants investigation.

Elevated jugular venous pressure (JVP) is abnormal, reflecting elevated right atrial pressure. Although edema is common in this population, it is important to evaluate neck veins in any pregnant woman with peripheral edema.

Elevated jugular venous pressure (JVP) is abnormal, reflecting elevated right atrial pressure. Although edema is common in this population, it is important to evaluate neck veins in any pregnant woman with peripheral edema.

Pulmonary hypertension (right ventricular heave, loud P2, JVP elevation) findings should be investigated early. Women with preexisting pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary pressure greater than 75% of systemic pressure) should be counseled prior to pregnancy as to the risks.

Pulmonary hypertension (right ventricular heave, loud P2, JVP elevation) findings should be investigated early. Women with preexisting pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary pressure greater than 75% of systemic pressure) should be counseled prior to pregnancy as to the risks.

Systolic murmur 3/6 or louder and any diastolic murmur audible in pregnancy are considered abnormal and warrant evaluation.

Systolic murmur 3/6 or louder and any diastolic murmur audible in pregnancy are considered abnormal and warrant evaluation.

Audible S4 is unusual during pregnancy and may reflect underlying hypertension.

Audible S4 is unusual during pregnancy and may reflect underlying hypertension.

7. What are the cardiac changes that occur during labor and delivery?

8. Which women should undergo infective endocarditis (IE) prophylaxis at the time of delivery?

IE prophylaxis is optional in vaginal delivery for patients with prior IE, prosthetic valves, and congenital heart disease (CHD) within the first 6 months of repair, or after 6 months if there is residual shunting, surgically constructed systemic-to-pulmonary shunts or conduits, or posttransplantation valvulopathy. It is not indicated in cesarean section, per 2007 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, although it is often given.

9. What maternal cardiac tests can be performed safely?

Electrocardiograms and echocardiograms are safe, with no known risk to the fetus.

Electrocardiograms and echocardiograms are safe, with no known risk to the fetus.

Chest radiographs can be performed with proper pelvic shielding.

Chest radiographs can be performed with proper pelvic shielding.

MRI is considered safe (although there is little data during the first trimester).

MRI is considered safe (although there is little data during the first trimester).

Low-level exercise tolerance testing to 70% of maternal maximal HR is safe with low risk of fetal distress or bradycardia.

Low-level exercise tolerance testing to 70% of maternal maximal HR is safe with low risk of fetal distress or bradycardia.

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can be performed with appropriate sedation and monitoring.

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can be performed with appropriate sedation and monitoring.

Cardiac catheterization, balloon valvuloplasty, angioplasty, and percutaneous intervention are invasive diagnostic and therapeutic tests that may be life saving to the mother with appropriate pelvic shielding for the fetus.

Cardiac catheterization, balloon valvuloplasty, angioplasty, and percutaneous intervention are invasive diagnostic and therapeutic tests that may be life saving to the mother with appropriate pelvic shielding for the fetus.

Computerized tomography is relatively contraindicated due to radiation risk to the fetus.

Computerized tomography is relatively contraindicated due to radiation risk to the fetus.

Nuclear imaging is contraindicated due to radiation risk to the fetus.

Nuclear imaging is contraindicated due to radiation risk to the fetus.

10. What are the highest-risk maternal cardiac conditions during pregnancy?

Moderate to severe mitral, aortic, and pulmonic stenosis are tolerated poorly during pregnancy. Patients should be counseled, with consideration of valvuloplasty or valve replacement before conception. These procedures can be performed during high-risk pregnancies if the patient decompensates. Pulmonary hypertension (pHTN) is also a high-risk condition, with historic maternal mortality rates of 30% to 56%. Although mortality remains unacceptably high, improvements in both the treatment of pHTN as well as the management of high-risk pregnancy have led to significant mortality reductions. Women with pHTN should be counseled regarding these risks. See Question 14 for discussion of CHD.

11. Are regurgitant lesions equally risky?

12. What are maternal complications seen in pregnant women with cardiac disease? What are some predictors of fetal complications?

13. How are pregnant women anticoagulated during pregnancy?

Aggressive adjusted-dose twice-daily low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) throughout pregnancy with doses adjusted to achieve target peak anti–activated factor X (anti-Xa) level 4 hours postinjection, or

Aggressive adjusted-dose twice-daily low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) throughout pregnancy with doses adjusted to achieve target peak anti–activated factor X (anti-Xa) level 4 hours postinjection, or

Aggressive adjusted-dose twice-daily unfractionated heparin (UFH) throughout pregnancy administered subcutaneously to a therapeutic PTT, or

Aggressive adjusted-dose twice-daily unfractionated heparin (UFH) throughout pregnancy administered subcutaneously to a therapeutic PTT, or

UFH or LMWH until week 13 of pregnancy with substitution by vitamin K antagonists (e.g., warfarin) until close to delivery. At that point UFH or LMWH is resumed.

UFH or LMWH until week 13 of pregnancy with substitution by vitamin K antagonists (e.g., warfarin) until close to delivery. At that point UFH or LMWH is resumed.

Long-term anticoagulants should be resumed postpartum with all regimens, as early as the same evening. Low-dose aspirin can be optionally added for high-risk patients with mechanical heart valves. Mothers taking warfarin may nurse after delivery.

14. How are the common congenital lesions tolerated during pregnancy?

15. Which cardiac arrhythmias can complicate pregnancy?

16. How do you treat a pregnant woman with an acute myocardial infarction?

17. How do women with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) tolerate pregnancy?

18. What are the recommendations for patients with Marfan syndrome?

19. Which commonly used cardiac medications should be avoided during pregnancy?

Common cardiac medications that should be avoided during part or all of pregnancy are listed in Box 51-1.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Bates, S.M., Greer, I.A., Middeldorp, S., et al. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, ed 9: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e691S–e736S.

2. Bédard, E., Dimopoulos, K., Gatzoulis, M.A. Has there been any progress made on pregnancy outcomes among women with pulmonary arterial hypertension? Eur Heart J. 2009;30:256–265.

3. Bonow, R.O., Carabello, B.A., Kanu, C., et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation. 2006;114:493–496.

4. Drenthen, W., Pieper, P., Roos-Hesselink, J., et al. Outcome of pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease: a literature review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2303–2311.

5. Elkayam, U., Bitar, F. Valvular heart disease in pregnancy, parts I (native) and II (prosthetic). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:223–230. 403–410

6. James, A.H., Brancazio, L.R., Price, T. Aspirin and reproductive outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;63:49–57.

7. Kusters, D.M., Lahsinoui, H.H., van de Post, J.A. Statin use during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;10:363–378.

8. Reimold, S.C., Rutherford, J.D. Clinical practice: valvular heart disease in pregnancy. N Eng J Med. 2003;349:52–59.

9. Weiss, B.M., Zemp, L., Seifert, B., et al. Outcome of pulmonary vascular disease in pregnancy: a systematic overview from 1978 through 1996. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1650–1657.

10. Wilson, W., Taubert, K., Gewitz, M., et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: Guidelines from the AHA. Circulation. 2007;116:1736–1754.