Health promotion

Introduction

It is interesting to note Beattie’s (1991) observation that the major healthcare professions claim increasingly that health promotion underpins practice: interesting because while copious literature on health promotion and nursing is readily accessible in any nursing library, the emphasis tends towards practice and doing. Fundamental questions then about purpose, fit with practice and scrutiny of the different theoretical approaches and their pertinence for nursing, particularly in relation to specialist areas of practice, remain as much an underdeveloped area now as in 1991.

This debate was given fresh impetus in the UK by The Health of the Nation (HoN), the Government strategy for health in England (Department of Health 1992). This placed health promotion explicitly on the nursing agenda in general, and on the emergency care agenda in particular as accidents were one of the five key areas of the strategy with The HoN (Department of Health 1993a, p. 10) highlighting that:

Further to this, Targeting Practice (Department of Health 1993b) and Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation (Department of Health 1999), both of which include accident prevention, emphasize how health promotion has become more of a UK NHS priority. Likewise, The NHS Plan (Department of Health 2000), Choosing Health (Department of Health 2004a), Better Information, Better Choices, Better Health (Department of Health 2004b), Benchmarks for Promoting Health (Department of Health 2006) and, for example, from an international perspective the US Healthy People 2010 (US Department of Health and Human Services 2000).

Health promotion framework

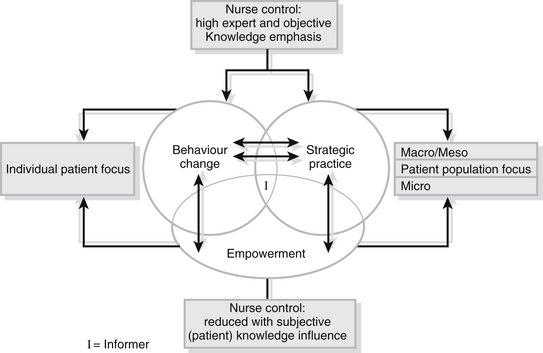

To facilitate conceptual understanding, contextualize and map out the models of health promotion Piper’s (2009) framework (Fig. 34.1), based on the work of Beattie (1991) and Piper & Brown (1998), is utilized. The framework comprises three models entitled The Nurse as Behaviour Change Agent, The Nurse as Strategic Practitioner and The Nurse as Empowerment Facilitator that derive from themes and deviant/paradigm cases generated in a qualitative study and constructive theorizing by the author to help illuminate the debate. As such, all require the tests of fit and transferability to be applied by the reader.

Similarly, when concerned with individual patient health promotion needs, The Nurse as Empowerment Facilitator converges with The Nurse as Behaviour Change Agent but is polarized on the power continuum where the former is concerned with a more bottom-up mode of intervention from an individual patient and subjective perspective. It converges with The Nurse as Strategic Practitioner when the focus of intervention is at a population level while remaining divergent in terms of the locus of control. However, given the nature of ED practice, the wider micro-population aspect of The Nurse as Empowerment Facilitator that goes beyond individual and immediate ED patient problems is not explored herein, but can be found in Chapter 8 of Piper (2009). Its concern with community development and social capital and seeking to improve health by encouraging and supporting the development of social networks and ‘social capital’ (Cooper et al. 1999) is not explored herein as this is more the domain of public health practitioners.

Operational definitions

To avoid the debate surrounding the distinction between health education and health promotion (this is explored in Piper (2009)), for the purpose of this chapter the definition of Tones (1990) is adopted. He states that health promotion: ‘incorporates all measures deliberately designed to promote health and handle diseases’ (Tones 1990, p. 3).

In addition, and consistent with Tones & Green (2004) and Piper (2009), primary, secondary and tertiary health promotion are defined as interventions that aim to:

• prevent new cases of disease or injury (primary)

• minimize the impact of disease or injury, prevent them from becoming chronic or irreversible and restore the patient to their former health status (secondary)

• maximize health experience within the context of chronic disease (e.g., diabetes, asthma, HIV), injury or disability, prevent further complications and assist rehabilitation (tertiary).

The nurse as behaviour change agent

The Nurse as Behaviour Change Agent reflects a ‘medical model’ approach to health promotion and is based on the assumption that individuals make rational, conscious decisions about their health-related behaviour. Primary interventions aim to prevent disease, illness and injury and promote optimum biological functioning by disseminating ‘factual’ information selectively derived from objective and medically based scientific research to the public. This takes the form of edicts from healthcare professionals, or the ever-present mass media awareness-raising campaigns such as the Clunk Click television car seatbelt campaigns of yesteryear, encouraging the use of cycle helmets, No Smoking Day and Drug Awareness Week, etc. It is suggested to the public that if they fail to follow a prescribed course of action their ‘health’ is at risk. The aim is to trigger a ‘do-it-yourself’ attitude and then behaviour/lifestyle changes consistent with the recommended advice given.

It is important to acknowledge that, while effective at raising awareness about particular health risks, the complexity of the relationship between social experience and health-related behaviour means that the outcomes are likely to be at best uncertain (Naidoo & Wills 2009). In emphasizing the personal controlling of risks and the correcting of individual inadequacies, it is assumed that free choice exists and that lifestyle is the primary cause of ill-health. In isolation such an approach denies that health is a social product, ignores and implicitly condones inequalities and minimal state intervention. For an excellent, albeit old and general (i.e., not related to nursing), critique of such a stance the reader is referred to Mitchell (1982); for a critique related to nursing, but not specific to ED, see Brown & Piper (1997) and Chapter 6 in Piper (2009).

At a simplistic level, elements of The Nurse as Behaviour Change Agent can be likened to an electrical system model (Hills 1979). This undermines the complexity of the nurse–patient interpersonal interaction by reducing it to a mechanistic relationship, but it serves a purpose and can be illustrated as follows:

The nurse provides the input and the coding and the patient is the decoder. The method is concerned with the sender (ED nurse/expert) validating facts and transmitting knowledge to the receiver (patient), with the latter feeding back information on how the sender’s messages have been received.

Ewles & Shipster (1984) take this one step further and refer to intervention of this nature as a three-stage process as follows:

• giving information or advice to a patient about his/her injury/disease

• ensuring that the patient understands and remembers that information or advice

• ensuring that the patient is able to act on the information or advice.

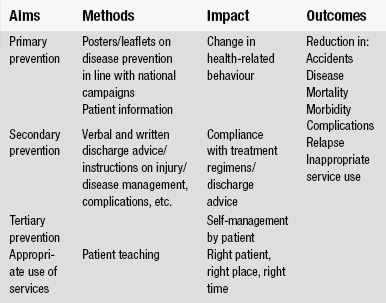

They stress the need to define the objectives and desired outcome for the intervention, to give the information in a structured way emphasizing and repeating the important aspects and the need to use short words and short sentences to avoid any misunderstanding. If there are any dangers with this important facet of ED nursing they are that the nurse tells rather than listens and adopts a didactic (Macleod Clark et al. 1991), top-down, one-way stance that reinforces their professional status and power base and engenders patient deference and dependence. In pursuing health promotion outcomes based on professionally determined needs there may also be a failure to consider the patient’s perception of their problems and solutions, their social, economic or environmental context or to achieve their participation in care. Examples of the aims, methods, impact and outcomes of The Nurse as Behaviour Change Agent are summarized in Table 34.1.

The nurse as strategic practitioner

Part of this model of practice fits with what Beattie (1991) refers to as ‘Legislative Action for Health’. Here, social factors and social conditions are seen as the major determinants of health status. Social class is considered to be beyond the control of individuals but instrumental in influencing their way of life and thus health status with poor health experiences and higher accident rates attributable to socio-economic inequalities (Townsend & Davidson 1990, Whitehead 1990, Acheson 1998, Department of Health 2002b, Marmot 2010).

Contributions to population (macro) health gain can be achieved by legislative and environmental interventions governing issues such as welfare provision, taxation, the distribution of resources and pollution. The action of industry and persuasive advertising can be monitored and controlled and laws can be enacted. With regard to the latter, and with a particular resonance for ED nurses, Tones & Tilford (2001) report that behaviour change based health promotion to encourage the wearing of front seatbelts was successful to a degree, but that legislation has been much more successful in enforcing their use and has changed the pattern of injury following a road traffic collision helping to reduce mortality and morbidity.

In line with this way of working, The Nurse as Strategic Practitioner approach could engage ED nurses in collecting data to construct a profile of the pattern of local accidents to use to campaign for traffic-calming measures in residential areas or improved street lighting. This would involve nurses lobbying local policy-makers by submitting written and verbal evidence to appropriate forums (within the boundaries of confidentiality and professional codes of conduct) and taking every opportunity to be involved in partnership and multi-agency working. Nationally, ED nurses can lobby power-holders through their professional organizations and specialist forums. Piper (2008) highlights that this is consistent with the UK Royal College of Nursing Emergency Nurses Association Conference (2008) encouraging Emergency Nurses to use their collective voice on issues beyond the confines of the ED. Collectively then, ED nurses can align themselves with pressure groups to address such issues as poverty and welfare provision, car design, drinking and driving, health and safety laws governing the workplace and advertising bans, e.g., tobacco, or the emphasis placed on the high performance of cars, etc.

More closely related to patients, Piper (2008) has applied this model of health promotion at a meso level (Tones & Tilford 2001), i.e., from an organizational perspective specifically to ED nursing. This is a settings approach to health promotion and derives from the concept of Health Promoting Hospitals (World Health Organization 1991, 1997, Dooris & Hunter 2007). From an ED perspective the focus is on resource management, clinical governance, health promotion quality and standards such as customer care (Rushmere 2000) and patient information (Groene 2006), education and training issues and collaborative care planning, all of which are concerned with promoting ED patient population health gain.

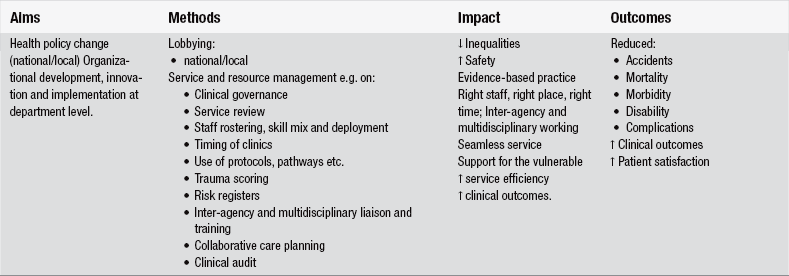

In addition, resource management can enhance standards of care delivery by effective skill mix, e.g., numbers of nurses on a shift having undergone recognized post-registration training courses and the careful deployment of senior ED staff so that patients’ needs are met by the most appropriate healthcare professional. Standard setting should state the quality levels expected within the department and be aligned with promoting evidence-based practice. Implementation of recognized processes such as trauma scoring, the use of nationally recognized protocols such as those for advanced life support, asthma, etc. and appropriate directives from the National Service Frameworks can also be closely monitored. These examples of how The Nurse as Strategic Practitioner might be adapted and applied by ED nurses are summarized in Table 34.2 in relation to the aims, methods, impact and outcomes of practice.

The nurse as empowerment facilitator

Of the previous strategies explored, The Nurse as Behaviour Change Agent and The Nurse as Strategic Practitioner involve professionally led direct and indirect health promotion, respectively, and a more traditional demeanour. Neither set out with the purpose of achieving health promotion outcomes in a patient-centred, non-hierarchical, non-coercive way aiming at active participation and thus pragmatic empowerment. The Nurse as Empowerment Facilitator, where the focus of intervention is the individual patient, seeks to achieve this by enabling patient reflection on and clarification of existing health-related behaviours and by facilitating informed choice.

While empowerment is a complex and contested concept (Lewin & Piper 2007, Piper 2009, 2010), this model of health promotion practice is flagged up because it fits with the developing consumer culture and moves to empower patients, for example, the UK Department of Health (2002a) policy ‘Patient and public involvement in health’. Examples of developments in this direction also include moves to actively promote an expert patient persona in those with chronic illness (Department of Health 2001) and representation for patients via patient advice and liaison services (Department of Health 2002a).

A model currently popular and compatible with The Nurse as Empowerment Facilitator is the Stages of Change (Prochaska & Diclemente 1982). A detailed outline of this work is beyond the scope of this chapter and the reader is referred to the authors’ original work for a clear exposition of this process and to Naidoo & Wills (2009). Briefly, however, the cycle has stages through which people who change successfully move whatever the variety of behaviour. ‘Contemplation’, the point at which people enter the cycle, represents a form of cognitive dissonance where people become aware of themselves, the nature of their behaviour and its negative consequences and think about the positive consequences of change. At this stage they continue the behaviour, e.g., smoking. ‘Action’ is when a person has decided to effect change, ‘Maintenance’ is the point at which there is a belief in the ability to maintain change and ‘Relapse’, an integral part of the cycle, is where the behaviour and contemplation or pre-contemplation stage is reverted to.

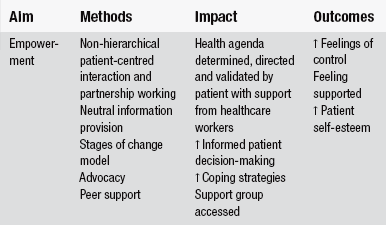

Where there is a micro-population empowerment role for ED nurses it is in acknowledging the impact of social factors on health, having a knowledge of national and local self-help and support groups and being able to direct appropriate patients towards these. This would necessitate accident departments holding directories of local activity and key contacts. Such groups help reduce isolation, enable patients and/or their relatives and loved ones to use their collective resources to determine their common needs, shape their agenda for ‘health’ and build support networks. The group members can share experiences, offer coping strategies and draw strength from each other. They can also challenge the medical and nursing professions and lobby for change in both service provision and societal attitudes. Examples of the aims, methods, impact and outcomes of The Nurse as Empowerment Facilitator are summarized in Table 34.3.

Conclusion

This chapter has endeavoured to combine a brief theoretical discussion on the nature of health promotion outlining a framework for practice and translating how the complementary and contradictory models within the framework, each with different aims, methods and outcomes, relate to ED nursing. It is the author’s contention that health promotion is an intrinsic part of holistic ED nursing and that the three models outlined enable legitimate ED health promotion activity, but to varying degrees. Clearly The Nurse as Behaviour Change Agent has considerable and obvious application for individual patients while the collective patient agenda can be addressed by The Nurse as Strategic Practitioner for indirect health gain. The contribution of the individual and micro-population Empowerment Facilitation model to ED nursing is perhaps more limited, but still has a place. In particular the former is important in terms of the absolute right of patients to have control over their own health and health-related decision making where possible and is in line with the developing consumer culture in healthcare. Finally, the author is aware that this chapter may re-label as health promotion, rather than re-shape, elements of existing practice.

References

Acheson, D. Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health Report. London: The Stationery Office; 1998.

Beattie, A. Knowledge and control in health promotion: a test case for social policy and social theory. In: Gabe J., Calnan M., Bury M., eds. The Sociology of the Health Service. London: Routledge, 1991.

Brown, P.A., Piper, S.M. Nursing and the health of the nation: schism or symbiosis? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25:297–310.

Cooper, H., Arber, S., Fee, L., et al. The Influence of Social Support and Social Capital on Health: A Review and Analysis of British Data. London: Health Education Authority; 1999.

Department of Health. The Health of the Nation: A Strategy for Health in England. London: HMSO; 1992.

Department of Health. The Health of the Nation: Key Area Handbook Accidents. London: HMSO; 1993.

Department of Health. Targeting Practice: The Contribution of Nurses, Midwives and Health Visitors. The Health of the Nation. London: HMSO; 1993.

Department of Health. Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation. London: HMSO; 1999.

Department of Health. The NHS Plan: A Plan for Investment, a Plan for Reform. London: HMSO; 2000.

Department of Health. The Expert Patient: A New Approach to Chronic Disease Management for the 21st Century. London: Department of Health; 2001.

Department of Health. Patient Advice and Liaison Service. London: Department of Health; 2002.

Department of Health. Tackling Health Inequalities: Summary of the Cross-cutting Review. London: Department of Health; 2002.

Department of Health. Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier. London: TSO; 2004.

Department of Health. Better Information, Better Choices, Better Health: Putting Information at the Centre of Health. London: Department of Health; 2004.

Department of Health. Benchmarks for Promoting Health. London: Department of Health; 2006.

Dooris, M., Hunter, D.J. Organisations and settings for promoting public health. In: Lloyd C.E., Handsley S., Douglas J., Earle S., Spurr S., eds. Policy and Practice in Promoting Public Health. London: Sage, 2007.

Ewles, L., Shipster, P. One to One Health Education. London: South East Thames Regional Health Authority; 1984.

Groene, O. Implementing Health and Promotion in Hospitals: Manual and Self-assessment Forms. Copenhagen: WHO Europe; 2006.

Hills, P. Teaching and Learning as a Communication Process. London: Croom Helm; 1979.

Lewin, D., Piper, S.M. Patient empowerment within a coronary care unit. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2007;23:81–90.

Lowthian, J.A., Curtis, A.J., Cameron, P.A., et al. Systematic review of trends in emergency department attendances: An Australian perspective. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2011;28(5):373–377.

Macleod Clark, J., Wilson-Barnett, J., Latter, S. Health Education in Nursing Project: Results of a National Survey on Senior Nurses’ Perceptions of Health Education Practice in Acute Ward Settings. London: Department of Nursing Studies, King’s College, University of London Education Authority; 1991.

Marmot, M., et al. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: Strategy Review of Health Inequalities in England Post 2010. The Marmot Review. London: Department of Health; 2010.

Mitchell, J. Looking after ourselves: an individual responsibility? Royal Society of Health Journal. 1982;4:169–173.

Naidoo, J., Wills, J. Foundations for Health Promotion, third ed. London: Elsevier; 2009.

Piper, S.M. Promoting health. Emergency Nurse. 2008;16(8):12–14.

Piper, S.M. Health Promotion for Nurses: Theory and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge; 2009.

Piper, S.M. Patient empowerment: Emancipatory or technological practice? Patient Education and Counselling. 2010;79(2):173–177.

Piper, S.M., Brown, P.A. The theory and practice of health education applied to nursing: a bi-polar approach. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;27:383–389.

Prochaska, J.O., Diclemente, C.C. Transtheoretical therapy: towards a more integrated model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 1982;19(2):276–288.

Rushmere, A. Health Promoting Hospitals and Trusts: Self Assessment and Peer Review Toolkit. Southampton: The Wessex Institute for Health Research and Development; 2000.

Tones, K. Why theorise? Ideology in Health Education. Health Education Journal. 1990;49(1):26.

Tones, K., Green, J. Health Promotion: Planning and Strategies. London: Sage; 2004.

Tones, K., Tilford, S. Health Education: Effectiveness, Efficiency and Equity, third ed. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes; 2001.

Townsend, P., Davidson, N. Inequalities in Health. The Black Report. London: Penguin; 1990.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

Whitehead, M. Inequalities in Health: The Health Divide. London: Penguin; 1990.

WHO. The Budapest Declaration on Health Promoting Hospitals. Geneva: WHO; 1991. [Budapest, Hungary, 31 May–1 June].

WHO, Health Promoting Hospitals: Working for Health, The Vienna Recommendations. 3rd workshop of National/Regional Health Promoting Hospitals Network Coordinators, Vienna, The Hospital Unit, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 1997.