Chapter 168 Health Advice for Children Traveling Internationally

The health risks and pretravel requirements for children traveling internationally, particularly those <2 yr of age, differ from those for adults. In the USA, recommendations and vaccine requirements for travel to different countries are provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and are available online at www.cdc.gov/travel/content/vaccinations.aspx.

General Travel Preparation

Underlying Medical Illness

Parents of traveling children should be asked whether the child has any current health problems or has had any problems in the past that have required medical evaluation or medication. Parents of children with medical conditions should take with them a brief medical summary and a sufficient supply of prescription medications for their children, with bottles that are clearly identified. For children requiring care by specialists, an international directory for that specialty can be consulted. A directory of physicians worldwide who speak English and who have met certain qualifications is available from the International Association for Medical Assistance to Travelers (www.iamat.org/index.cfm). If medical care is needed urgently when abroad, sources of information include the American embassy or consulate, hotel managers, travel agents catering to foreign tourists, and missionary hospitals.

Immunizations

In general, live-virus vaccines (measles, varicella, live-attenuated influenza) and live bacterial vaccines (bacille Calmette-Guérin [BCG], oral typhoid) are contraindicated in immunocompromised persons. However, HIV-infected children who are not severely immunocompromised should receive measles and varicella vaccines (see Table 165-6). Asymptomatic HIV-infected children may also be vaccinated against yellow fever if the risk is significant, but children with symptomatic HIV infection should not receive yellow fever vaccine. Inactivated vaccines and toxoids are not contraindicated in immunocompromised children but may be associated with diminished immune responses.

Routine Childhood Vaccines

All children who travel should be immunized according to the routine childhood immunization schedule with all vaccines appropriate for their age (Chapter 165). The immunization schedule can be accelerated to maximize protection for traveling children, especially for unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated children (see Fig. 165-4).

Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis

Infants and children <7 yr old who have not completed the series may be immunized using an accelerated schedule in preparation for international travel (see Fig. 165-4). There is some protection after 2 doses 4 wk apart, but there is little benefit with only 1 dose.

Haemophilus Influenzae Type B

H. influenzae type b remains the leading cause of meningitis in children 6 mo to 3 yr of age in many developing countries. Before they travel, all unimmunized children <60 mo of age and all children with chronic illness at risk for H. influenzae type b infections should be vaccinated (Chapter 165). If a child <15 mo is unvaccinated, ≥2 doses 4 wk apart starting no younger than 6 wk of age should be given before travel. Between 15 and 59 mo, 1 dose should be given. Unvaccinated children >59 mo of age do not need vaccination unless they are at risk due to an immunosuppressive condition.

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is highly prevalent in eastern and southeastern Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Pacific basin. In certain parts of the world, 8-15% of the population may be chronically infected. Disease can be transmitted via blood transfusions not screened for hepatitis B surface antigen, exposure to unsterilized needles, close contact with local children who have open skin lesions, and sexual exposure. Exposure to hepatitis B is more likely for travelers residing for prolonged periods in endemic areas. Partial protection may be provided by 1 or 2 doses, but ideally 3 doses should be given before travel. See Figure 165-4 for the accelerated schedule. For unvaccinated adolescents, the first 2 doses are 4 wk apart, followed by a third dose 4-6 mo after the second one.

Measles, Mumps, and Rubella

Measles is still endemic in many developing countries and in some industrialized nations. Measles vaccine, preferably in combination with mumps and rubella vaccines (MMR), should be given to all children at 12-15 mo of age and at 4-6 yr of age, unless there is a contraindication (Chapter 165). In children traveling internationally, the second vaccination can be given as soon as 4 wk after the first. In the accelerated schedule, the first MMR vaccination can be given to children as young as 6 mo of age, but if the vaccine is given earlier than 12 mo of age, the child should be considered unvaccinated and given 2 additional doses ≥4 wk apart after 12 mo of age (see Fig. 165-4). Infants <6 mo of age are protected by maternal antibodies. HIV-infected children who travel abroad should be vaccinated unless they are severely immunocompromised (Chapter 268), because measles in HIV-infected children can be a devastating illness.

Pneumococcus

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the leading cause of bacterial pneumonia and among the leading causes of bacteremia and bacterial meningitis in children in developing and industrialized nations. Immunization against S. pneumoniae with a protein-conjugated pneumococcal vaccine is now part of routine childhood immunization in the USA. Unimmunized children should be immunized if they are at high risk, such as children with sickle cell disease, asplenia, HIV infection, congenital immunodeficiency, nephrotic syndrome, or chronic cardiac or pulmonary disease and those on immunosuppressive medication (Chapter 165). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that these children receive both the conjugate pneumococcal vaccine and the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine ≥8 wk after the last conjugate vaccine dose. The ACIP also recommends that vaccination with conjugate pneumococcal vaccine be considered in all healthy unimmunized children 24-59 mo of age with 1 dose; conjugate pneumococcal vaccination of unimmunized children in this age group traveling internationally should be strongly considered for unvaccinated children between 6 wk and 12 mo of age should receive 2-3 doses of conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (depending on the age when starting the series) ≥4 wk apart with a booster at age 12-15 mo. For unvaccinated children ages 12-23 mo, 2 doses should be given ≥8 wk apart.

Poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis was eradicated from the Western hemisphere in 1991 but remains endemic in several developing countries, and the 2004 epidemic in Nigeria underscored the importance of vaccination for preventing this disease. The poliovirus vaccination schedule in the USA is now a 4-dose, all-inactivated poliovirus (IPV) regimen (Chapter 165). Oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) is no longer available in the USA. Unvaccinated adults who are at increased risk for exposure to poliovirus and who cannot complete the recommended IPV regimen (0, 1-2, and 6-12 mo) should receive 3 doses of IPV given ≥4 wk apart. For an accelerated dosing schedule for children, see Figure 165-4. Length of immunity conferred by IPV immunization is not known; a single booster dose of IPV is recommended for fully vaccinated adults traveling to endemic areas. Proof of vaccination is required to enter Saudi Arabia for the Hajj.

Varicella

All children ≥12 mo of age who have no history of varicella vaccination or chickenpox should be vaccinated unless there is a contraindication to vaccination (Chapter 165). Infants <6 mo of age are generally protected by maternal antibodies. All children now require 2 doses, the first at 12 mo of age, and the second at 4-6 yr of age. The second dose can be given as soon as 3 mo after the first dose. For unvaccinated children ≥13 yr of age, the first and second doses can be separated by 4-8 wk.

Travel Vaccines

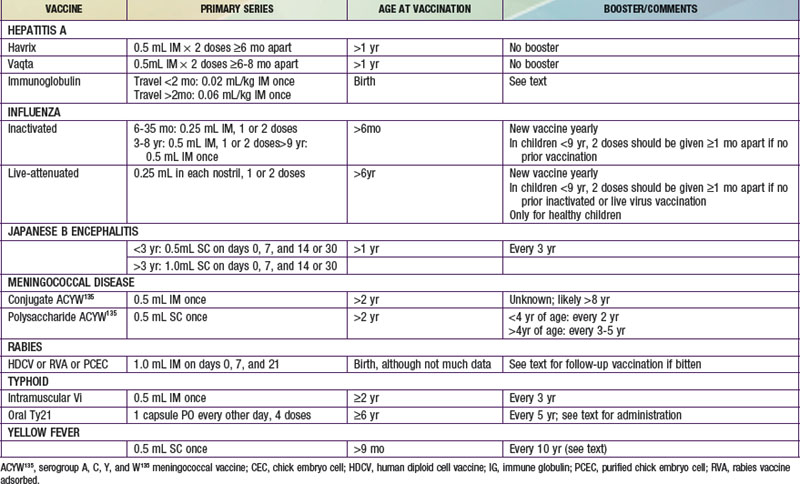

The dosages and age restrictions of vaccines specifically given to children traveling internationally are summarized in Table 168-1.

Influenza and Avian Influenza

The risk for exposure to influenza during international travel varies depending on the time of year, destination, and intermingling of persons from different parts of the world where influenza may be circulating. In tropical areas influenza can occur throughout the year, whereas in the temperate regions of the Southern hemisphere, most activity occurs from April through September. In the Northern hemisphere, influenza generally occurs from November through March. Influenza vaccination is strongly recommended for children ≥6 mo to 5 yr old and all other children who are at increased risk for complications of influenza, including those with chronic medical conditions (chronic cardiac, renal, or pulmonary disease, immunosuppressive conditions or therapy, HIV infection, sickle cell disease, and diabetes mellitus) (Chapter 165). The AAP now recommends universal immunization for all healthy children from 6 mo to 18 yr old. The live-attenuated vaccine (administered nasally) can be given to healthy children. However, the list of medical contraindications to this vaccine should be reviewed carefully (Chapter 165). Children with any of these conditions should receive only the inactivated vaccine.

Meningococcus

Neisseria meningitidis causes epidemic and endemic disease worldwide (Chapter 184).

Most cases occur in the “meningitis belt” of sub-Saharan Africa (see the map at www.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2008/ch4/menin.aspx) between December and June. Epidemics have also occurred in the Indian subcontinent and Saudi Arabia, especially among pilgrims to the Hajj. Cases in American travelers are rare, and vaccination is indicated primarily in travelers to an area with an active outbreak or those who might have prolonged contact with the local population in an endemic area, especially in crowded conditions. Saudi Arabia requires all pilgrims to Mecca to have documentation of meningococcal vaccination ≥10 days and within 3 yr before arrival. Serogroup A is the most common cause of epidemics outside the USA, but serogroup C and, rarely, serogroup B have also been associated with epidemics.

Typhoid

Salmonella typhi infection, or typhoid fever, is common in many developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America (Chapter 190). Typhoid vaccination is recommended for children traveling to the Indian subcontinent (the area of highest risk) and for persons traveling to endemic areas who are at higher risk for infection (visits >4 wk, backpackers, and travelers staying with friends or relatives in developing countries). Vaccination should be strongly considered for all children traveling to endemic areas, especially if exposure to contaminated food and water is likely.

Traveler’s Diarrhea

Traveler’s diarrhea, characterized by a 2-fold or greater increase in the frequency of unformed bowel movements, occurs in as many as 40% of all travelers overseas (Chapter 332.1). Children, especially those <3 yr of age, have a higher incidence of diarrhea, more severe symptoms, and more-prolonged symptoms than adults, with a reported attack rate of 60% for those <3 yr old in one study. Traveler’s diarrhea is usually acquired through ingestion of fecally contaminated food and water. Diverse infectious agents (bacteria, viruses, and parasites) have been associated with traveler’s diarrhea, but enterotoxigenic E. coli is still the most common cause. Other bacterial causes include Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Aeromonas hydrophilia, and Plesiomonas shigelloides. Protozoan infections such as Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium parvum, and Isospora are more common in long-term travelers. Rotavirus has also been associated with traveler’s diarrhea.

Malaria Chemoprophylaxis

Malaria, a mosquito-borne infection, is the leading parasitic cause of death in children worldwide (Chapter 280). Of the 4 Plasmodium species that infect humans, P. falciparum causes the greatest morbidity and mortality. Each year, >8 million U.S. citizens visit parts of the world where malaria is endemic (sub-Saharan Africa, Central and South America, India, Southeast Asia, Oceania). Children accounted for 15-20% of imported malaria cases in a WHO study in Europe. Given the major resurgence of malaria and increased travel among families with young children, physicians in developed countries are increasingly required to give advice on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of malaria. Case fatality of imported malaria remains <1% in children from nonendemic countries;, however, risk factors for severe malaria and death include inadequate adherence to chemoprophylaxis, delay in seeking medical care, delay in diagnosis, and nonimmune status. The CDC maintains updated information at www.cdc.gov/malaria/travelers/index.html, as well as a malaria hotline for physicians (770-488-7788). It is important to check this updated information, because recommendations for prophylaxis and treatment are often modified owing to changes in the risk for developing malaria in different areas of the world, changing Plasmodium resistance patterns, and the availability of new antimalarial medications.

Avoidance of mosquitoes and barrier protection from mosquitoes are an important part of malaria prevention for travelers to endemic areas. The Anopheles mosquito feeds from dusk to dawn. Travelers should remain in well-screened areas, wear clothing that covers most of the body, sleep under a bed net (ideally one impregnated with permethrin), and use insect repellents with DEET, during these hours (see “Infectious Disease Precautions”). Parents should be discouraged from taking a young child on a trip that will entail evening or nighttime exposure in areas endemic for P. falciparum.

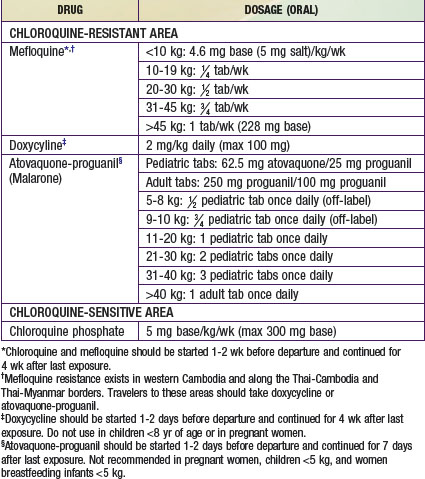

Resistance of P. falciparum to the traditional chemoprophylactic agent, chloroquine, is rapidly increasing worldwide, and in most areas of the world other agents must be used (Table 168-2). Factors that must be considered in choosing appropriate chemoprophylaxis medications and dosing schedules include age of the child, travel itinerary (including whether the child will be traveling to areas of risk within a particular country and whether chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum is present in the country), vaccinations being given, allergies or other known adverse reactions to antimalarial agents, and the availability of medical care during travel.

Table 168-2 CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS OF MALARIA FOR CHILDREN

In areas of the world where P. falciparum remains fully chloroquine sensitive (Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Central America north of the Panama Canal, and some countries in the Middle East), weekly chloroquine is the drug of choice for malaria chemoprophylaxis. Updated information on chloroquine susceptibility and recommended malaria prophylaxis is available at www.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2010/chapter-2/malaria.aspx.

The Returning Traveler

There is very little literature that specifically addresses the causes of illness in children returning from travel. Among all persons returning from travel (children and adults), four major patterns of illness have been noted (Table 168-3). The etiology of each of these disease presentations in part depends on the country visited. Dengue is not common in returning visitors from sub-Saharan Africa, but tick-borne spotted fever is common in sub-Saharan Africa. Malaria is noted in most developing countries. Children returning from international travel who have specific signs and symptoms of illness, such as fever, rash, and acute or chronic diarrhea, should be seen in consultation with a pediatric travel medicine or infectious disease specialist.

Table 168-3 PATTERNS OF ILLNESS AMONG RETURNING INTERNATIONAL TRAVELERS

SYSTEMIC FEBRILE ILLNESS

ACUTE DIARRHEA

DERMATOLOGIC MANIFESTATIONS

Fever is a particularly worrisome symptom. Malaria and typhoid are the two most common causes of fever in children returning from travel to developing countries, but numerous other illnesses acquired in these countries can cause fever (see Table 168-3). Malaria must be considered in the evaluation of any fever that develops within 1 yr, and particularly within the first 2 mo, after travel to malaria-endemic areas. Other symptoms of malaria can be nonspecific and include malaise, GI complaints, headache, myalgias, cough, and neurologic complaints. Children are more likely than adults to have GI symptoms, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, jaundice, and anemia as well as higher fevers. Thrombocytopenia (without increased bleeding) and fever in a child returning from an endemic area is highly suggestive of malaria. Thick and thin blood smears need to be performed for diagnosis is malaria is clinically suspected. If results are negative initially, ≥2 additional smears should be done 12-24 hr after the initial smear. Treatment should be initiated immediately once the diagnosis is confirmed or empirically if presentation is severe with suspected malaria. Given their increased risk for severe malaria, children should be hospitalized initially even for cases of uncomplicated malaria. Treatment should be determined in consultation with a pediatric infectious disease specialist and the CDC, which has updated information on the drugs of choice, which are similar to those for adults (see Chapter 280 for more details on malaria infection).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of reduced (4-dose) vaccine schedule for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent human rabies. MMWR. 2010;59(RR-2):1-9.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human infection with avian influenza A (H5N1) virus: advice for travelers. 2008 (website). www.cdc.gov/travel/contentAvianFluAsia.aspx.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International travel with infants and young children, Yellow Book. www.cdc.gov/travel/yellowBookCh8-SafeInfantsChildren.aspx, 2008.

Giovanetti F. Immunisation of the travelling child. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2007;5(6):349-364.

Ladhani S, Aibara RJ, Riordan FA, et al. Imported malaria in children: a review of clinical studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:349-357.

Lee PJ. Vaccines for travel and international adoption. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:351-354.

Mackell S. Traveler’s diarrhea in the pediatric population: etiology and impact. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:S547-S552.

Shetty AK, Woods CR. Prevention of malaria in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:1173-1176.

Stauffer W, Christenson JC, Fischer PR. Preparing children for international travel. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2008;6:101-113.

Wilson ME, Weld LH, Boggild A, et al. Fever in returned travelers: results from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1560-1568.