Chapter 588 Headaches

588.1 Migraine

Classification and Clinical Manifestations

Criteria have been established to guide the clinical and scientific study of headaches; these are summarized in The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition (ICHD-II). The different clinical types of migraine are contrasted in Table 588-1. The specific criteria for migraine without aura and migraine with aura are listed in Table 588-2.

Table 588-1 INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF HEADACHE DISORDERS, 2ND EDITION*

| MIGRAINE | ICHD-II CODE |

|---|---|

| Migraine without aura | 1.1 |

| Migraine with aura | 1.2 |

| Typical aura with migraine headache | 1.2.1 |

| Typical migraine with nonmigraine headache | 1.2.2 |

| Typical aura without headache | 1.2.3 |

| Familial hemiplegic migraine | 1.2.4 |

| Sporadic hemiplegic migraine | 1.2.5 |

| Basilar-type migraine | 1.2.6 |

| Childhood periodic syndromes that are commonly precursors of migraine | 1.3 |

| Cyclic vomiting | 1.3.1 |

| Abdominal migraine | 1.3.2 |

| Benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood | 1.3.3 |

| Retinal migraine | 1.4 |

| Complications of migraine | 1.5 |

| Chronic migraine | 1.5.1 |

| Status migrainosus | 1.5.2 |

| Persistent aura without infarction | 1.5.3 |

| Migrainous infarction | 1.5.4 |

| Probable migraine | 1.6 |

* Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society: The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition, Cephalalgia 24(Suppl 1):9–160, 2004.

Table 588-2 ICHD-II CRITERIA FOR MIGRAINE WITHOUT AURA AND MIGRAINE WITH AURA*

MIGRAINE WITHOUT AURA (ICHD-II, 1.1)

MIGRAINE WITH AURA, TYPICAL (ICHD-II, 1.2.1)

Migraine without Aura

Migraine without aura is the most common form of migraine in both children and adults. The ICHD-II (see Table 588-2) requires this to be recurrent (at least 5 headaches that meet the criteria, but there is no time limit over which this must occur). The recurrent episodic nature helps differentiate this from a secondary headache, as well as separates migraine from tension-type headache, but may limit the diagnosis in children as they may just be beginning to have headaches.

Migraine with Aura

The aura associated with migraine is a neurologic warning that a migraine is going to occur. In the common forms this can be the start of a typical migraine or a headache without migraine, or it may even occur in isolation. For a typical aura, the aura needs to be visual, sensory, or dysphasic, lasting longer than 5 min and less than 60 min with the headache starting within 60 min (see Table 588-2). The importance of the aura lasting longer than 5 min is to differentiate the migraine aura from a seizure with a postictal headache, while the 60 min maximal duration is to separate migraine aura from the possibility of a more prolonged neurologic event such as a transient ischemic attack.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Neuroimaging is warranted when the neurologic examination is abnormal or unusual neurologic features occur during the migraine; when the child has headaches that awaken him or her from sleep or that are present on first awakening and remit with upright posture; when the child has brief headaches that only occur with cough or bending over; and when the child has migrainous headache with an absolutely negative family history of migraine or its equivalent (e.g., motion sickness, cyclic vomiting) (Table 588-3). In this case, an MRI is the imaging of choice as it provides the highest sensitivity of detecting posterior fossa lesions and does not expose the child to radiation. The greatest concern in younger children is sedation for the MRI. Special attention should be paid if the location of the pain is exclusively occipital as this has been associated with a higher risk of an underlying pathologic process.

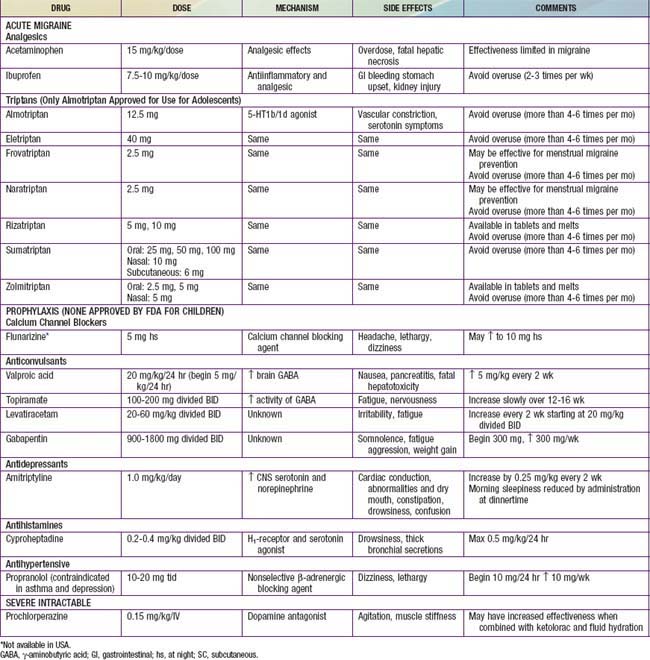

Treatment (TABLE 588-4)

In order to accomplish these goals, 3 components need to be incorporated into the treatment plan:

Abu-Arafeh I, Russell G. Prevalence of headache and migraine in schoolchildren. BMJ. 1994;309:765-769.

Anttila V, Stefansson H, Kallela M, et al. Genome-wide association study of migraine implicates a common susceptibility variant on 8q22.1. Nat Genet. 2010;42(10):869-873.

Avraham SB, Har-Gil M, Watemberg N. Acute confusional migraine in an adolescent: response to intravenous valproate. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e956-e959.

Berger K, Evers S. Migraine with aura and the risk of increased mortality. BMJ. 2010;341:465-466.

Bille B. Migraine in school children. Acta Paediatrica. 1962;51:16-151.

Bruijn J, Locher H, Passchier J, et al. Psychopathology in children and adolescents with migraine in clinical studies: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010;126:323-332.

Crawford MJ, Lehman L, Slater S, et al. Menstrual migraine in adolescents. Headache. 2009;49:341-347.

Dodick DW. Prevention of migraine. BMJ. 2010;341:5229.

Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2010;50:921-936.

Edvinsson L. CGRP-receptor antagonism in migraine treatment. Lancet. 2008;372:2089-2090.

Edvinsson L, Linde M. New drugs in migraine treatment and prophylaxis: telcagepant and topiramate. Lancet. 2010;376:645-654.

Evans RW. Treating migraine in the emergency department. BMJ. 2008;336:1320.

Fernstermacher N, Levin M, Ward T. Pharmacological prevention of migraine. BMJ. 2011;342:d583.

Francis GJ, Becker WJ, Pringsheim TM. Acute and preventive pharmacologic treatment of cluster headache. Neurology. 2010;75:463-473.

Fumal A, Vandenheede M, Coppola G, et al. The syndrome of transient headache with neurological deficits and CSF lymphocytosis (HaNDL): electrophysiological findings suggesting a migrainous pathophysiology. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:754-758.

Graf WD, Kayyali HR, Abdelmoity AT, et al. Incidental neuroimaging findings in nonacute headache. J Child Neurol. 2010;25(10):1182-1187.

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):9-160.

Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, et al. PedMIDAS: development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology. 2001;57:2034-2039.

Holroyd KA, Bendtsen L. Tricyclic antidepressants for migraine and tension-type headaches. BMJ. 2010;341:5250.

Lewis DW. Pediatric migraine. Neurol Clin. 2009;27:481-501.

Lewis DW, Ashwal S, Dahl G, et al. Practice parameter: evaluation of children and adolescents with recurrent headaches: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2002;59:490-498.

Lewis DW, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents. Neurology. 2004;63:2215-2224.

Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice Parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents: report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;63:2215-2224.

Lewis D, Winner P, Saper J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of topiramate for migraine prevention in pediatric subjects 12 to 17 years of age. Pediatrics. 2009;123:924-934.

Loder E. Triptan therapy in migraine. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:63-70.

Mariotti P, Nociti V, Cianfoni A, et al. Migraine-like headache and status migrainosus as attacks of multiple sclerosis in a child. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e459-e464.

The Medical Letter. Botulinum toxin for chronic migraine. Med Lett. 2011;53(1356):7.

The Medical Letter. A fixed-dose combination of sumatriptan and naproxen for migraine. Med Lett. 2008;50:45-46.

Pascual J, Valle N. Pseudomigraine with lymphocytic pleocytosis. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2003;7:224-228.

Rundek T, Elkind MSV, Di Tullio MR, et al. Patent foramen ovale and migraine. Circulation. 2008;118:1419-1424.

Silberstein SD, Rosenberg J. Multispecialty consensus on diagnosis and treatment of headache. Neurology. 2000;54:1553.

Split W, Neuman W. Epidemiology of migraine among students from randomly selected secondary schools in Lodz. Headache. 1999;39:494-501.

588.2 Secondary Headaches

Headaches can be a common symptom of other underlying illnesses. In recognition of this, the ICHD-II has classified the potential secondary headaches (Table 588-5). The key to the diagnosis of a secondary headache is to recognize the underlying cause and demonstrate a direct cause and effect. Until this has been demonstrated the diagnosis is speculative. This is especially true when the suspected etiology is common.

| DIAGNOSIS | ICHD-II CODE |

|---|---|

| Headache attributed to head and/or neck trauma | 5 |

| Acute post-traumatic headache | 5.1 |

| Chronic post-traumatic headache | 5.2 |

| Headache attributed to cranial or cervical vascular disorder | 6 |

| Headache attributed to nonvascular intracranial disorder | 7 |

| Headache attributed to high cerebrospinal fluid pressure | 7.1 |

| Headache attributed to low cerebrospinal fluid pressure | 7.2 |

| Headache attributed to intracranial neoplasm | 7.4 |

| Headache attributed to epileptic seizure | 7.6 |

| Headache attributed to a substance or its withdrawal | 8 |

| Medication-overuse headaches | 8.2 |

| Headache attributed to infection | 9 |

| Headache attributed to disorder of homeostasis | 10 |

| Headache of facial pain attributed to disorder of cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth, or other facial or cranial structures | 11 |

| Headache attributed to rhinosinusitis | 11.5 |

| Headache attributed to psychiatric disorder | 12 |

Arruda MA, Guidetti V, Galli F, et al. Frequent headaches in the preadolescent pediatric population. Neurology. 2010;74:903-908.

Burns B, Watkins L, Goadsby PJ. Treatment of medically intractable cluster headache by occipital nerve stimulation: long-term follow-up of eight patients. Lancet. 2007;369:1099-1106.

Cady RK, Schreiber CP. Sinus headache: a clinical conundrum. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2004;37:267-288.

Cohen AS, Burns B, Goadsby PJ. High-flow oxygen for treatment of cluster headache. JAMA. 2009;302:2451-2457.

2010 Management of medication overuse headache. BMJ. 2010;340:c1305.

Fuller G, Kaye C. Headaches. BMJ. 2007;334:254-256.

Hagen K, Albretsen C, Vilming ST, et al. Management of medication overuse headache: 1-year randomized multicentre open-label trial. Cephalalgia. 2008;29:221-232.

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):9-160.

Newton RW. Childhood headache. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2008;93:105-111.

588.3 Tension-Type Headaches

Treatment of TTH can require acute therapy to stop attacks, preventive therapy when frequent or chronic and behavioral therapy. It is often suspected that there may be underlying psychologic stressors (hence the misnomer as a “stress” headache), but this is often difficult to identify in children, and although it may be suspected by the parents, it cannot be confirmed in the child. Studies of and conclusive evidence to guide the treatment of TTH in children are lacking, but the same general principles and medications used in migraine can be applied to children with TTH (see Chapter 588.1). Oftentimes, simple analgesics (ibuprofen or acetaminophen) can be effective for acute treatment. Amitriptyline has the most evidence of effective prevention of TTH, while biobehavioral intervention, including biofeedback-assisted relaxation training and coping skills training may also be beneficial.

Harden RN, Cottrill J, Gagnon CM, et al. Botulinum toxin A in the treatment of chronic tension-type headache with cervical myofascial trigger points: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Headache. 2009;49:732-743.

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):9-160.

Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR. Chronic daily headache in adolescents. Neurology. 2009;73:416-422.

Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, et al. Outcomes and predictors of chronic daily headache in adolescents. Neurology. 2007;68:591-596.