chapter 9

Headache and Facial Pain

Headache is one of the commonest problems encountered in neurology. This chapter is not intended to be a comprehensive review of headache. The approach to the more common headache and facial pain syndromes encountered in clinical practice will be discussed. There are many excellent textbooks that contain more detailed information [1–5].

The various labels given to different types of headache have arisen from clinicians observing recurring patterns of similar symptoms in large number of patients in the absence of any gold standard for the diagnosis. Thus, the diagnosis of the cause of most headaches or facial pain is almost entirely dependent on a detailed and accurate history because, at this point in time, there are no diagnostic tests to confirm most of the common causes of headache such as migraine, cluster and tension-type headache. Imaging techniques such as computerised tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detect abnormalities that can explain the clinical presentation in only 2% of cases [6].

Consider the following case history:

Write down your diagnosis or diagnoses for Case 9.1 below before reading on.

Most students will say subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), some will say meningitis or migraine but in fact this young man had a hangover! All four diagnoses will result in headache, nausea, vomiting and photophobia. Although fever should differentiate SAH from meningitis, migraine and hangovers and neck stiffness should raise the suspicion of SAH or meningitis, occasionally patients with migraine complain of neck stiffness and rarely fever [7]. Similarly, if a young man had been out drinking heavily the night before, it would be wrong to assume he had a hangover if he experienced the thunderclap onset of severe generalised headache with nausea and vomiting as this is more in keeping with a SAH. This case reiterates the point made in Chapter 2, ‘The neurological history’, which is that the nature and distribution of symptoms DO NOT define the aetiology. The time course (mode of onset and subsequent progression of symptoms) will differentiate between these various entities, with the headache of SAH being of sudden onset and maximum severity at onset, whereas the headache of migraine, meningitis and that of a hangover will usually evolve over a variable period of time from minutes to hours.

The International Headache Society [8] classifies headaches as:

• primary – migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache and other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, other primary headaches

• secondary – headache due to another disorder that resolves within 3 months of treatment of that disorder.

Most patients with headache fear they may have a brain tumour. Although headache is a common symptom of a brain tumour, brain tumour as a cause of headache is extremely rare [9].

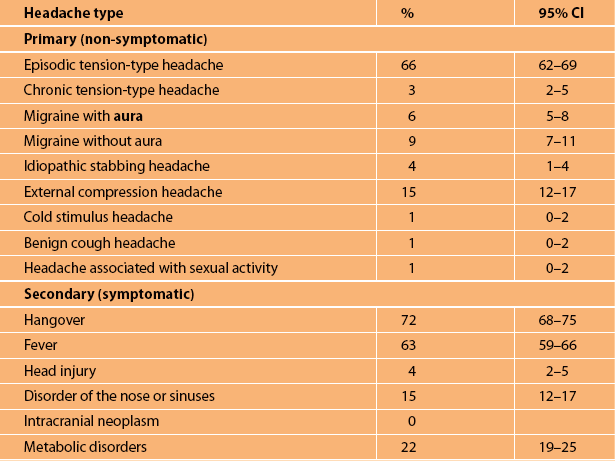

The commonest causes are the primary headache syndromes such as episodic tension-type headache and migraine and the commonest secondary causes are a hangover and fever [10] (see Table 9.1).

TABLE 9.1

Note: The International Headache Society criteria current at the time of the study were used.

Note: Figures are derived from a random sample of 925 individuals from the community in Denmark [10]. External compression headache relates to compression by helmets or swimming goggles. The prevalences are likely to be similar in other countries.

WHAT QUESTIONS TO ASK

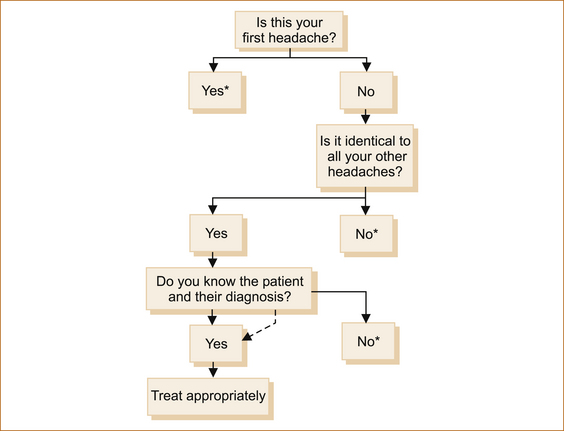

There are three scenarios (see Figure 9.1):

1. It is the first headache that the patient has ever experienced.

2. It is an identical headache in a patient who suffers from recurrent headaches.

3. It could be a completely different headache in a patient who has suffered from recurrent headaches.

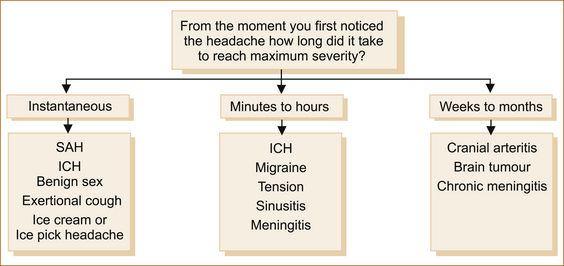

Use the technique below to obtain a blow-by-blow description, similar to that outlined in Chapter 2, ‘The neurological history’. Enquire what the patient was doing at the precise moment the headache commenced; what they had been doing just prior to this; what was the time from the onset of the headache until the headache reached its maximum severity; what were the exact nature, distribution and time taken to reach maximum intensity or extent of involvement of the body; what was the duration of all associated symptoms and the time they took to resolve, both individually and in relation to each other. Ascertaining the time taken to reach maximum intensity is the vital clue as to the likely pathological process.

Classical teaching has suggested students ask: whether the headache is unilateral or bilateral; constant or throbbing; frontal, temporal, parietal or occipital; made worse by straining, moving or coughing; whether it awakens the patient from sleep; and whether there is associated photophobia or phonophobia. In most instances the answers to these questions are unhelpful. As anyone who has suffered from migraine, tension-type headaches or hangovers will know, most of these features are non-specific (as highlighted in Case 9.1 above). Although migraine (see below) is typically a unilateral, throbbing headache associated with visual, gastrointestinal or neurological symptoms, it can be bilateral, constant and is not always accompanied by associated symptoms. Although trigeminal neuralgia is almost exclusively unilateral pain, cases of bilateral pain have been described and are more likely to represent symptomatic (underlying pathology other than compression of the nerve by a vascular loop) trigeminal neuralgia [11]. Similarly, cluster headache is unilateral but even here atypical cases with bilateral headache occur [12–14].

Obtaining a detailed history

A recommended approach when taking a history is:

1. What were you doing at the time (circumstances) the headache first commenced?

2. What had you been doing beforehand?

3. What was the first thing you noticed and how long did it take from when you first noticed this symptom until it reached its maximum severity?

4. What was the next thing you noticed and how long did it take from when you first noticed this symptom until it reached its maximum severity?

6. And then what happened? and so on, until the entire episode is described from start to finish.

Case 9.2 demonstrates the value of this history-taking technique.

The value of this method of obtaining histories can also be highlighted by re-examining the Case 9.1 which was described at the beginning of this chapter.

This is a typical history of someone with either migraine or suffering from a hangover. The presence of photopsia and neurological symptoms would indicate a likely diagnosis of migraine.

In this patient, symptoms evolved gradually with the initial symptoms disappearing before subsequent symptoms either developed or reached their maximum intensity, typical of a migraine. The last two questions would strengthen the diagnosis had the answer been yes, but remember that a past or a family history of migraine is circumstantial evidence (see Chapter 2, ‘The neurological history’).

In the next example, once again the initial presenting symptoms appear identical.

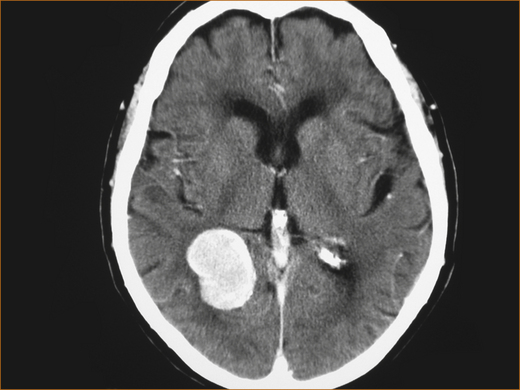

The above discussion would suggest that taking a history from patients with headache is easy. Unfortunately this is not always the case. The CT scan in Figure 9.2 is from a patient who was incapable of giving a detailed history because of the cognitive impairment resulting from the hydrocephalus. The patient complained of vague headache, non-descript blurring of vision and a change in her personality (her sister’s psychiatrist had diagnosed schizophrenia when her sister told him about her symptoms). The two clues to the underlying diagnosis were the fact that her legs gave way when her brother hugged her (this would have increased intrathoracic and intracranial pressure) and the presence of papilloedema when examined.

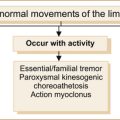

There are many different ways to approach patients with headache. The International Headache Society classification is into primary and secondary headache. In clinical practice when evaluating patients with headache there are three broad categories based on the rapidity of onset of the headache (see Figure 9.3).

A SINGLE (OR THE FIRST) EPISODE OF HEADACHE

Sudden onset ‘thunderclap headache’

All these conditions have one thing in common and that is the sudden onset of severe headache. (The slight exception is the headache related to exertion or orgasm; see below.) What differentiates one from the other are the associated symptoms, the duration of the headache and, to a lesser extent, the circumstances under which the headache occurs. It is important to remember that the most lethal condition NOT to miss is a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) and that it can occur under any circumstances including when patients exert themselves, cough, sneeze or during sexual intercourse. There are extremely rare causes of sudden severe headache such as hydrocephalic attack with or without the presence of a third ventricular colloid cyst acting as a ball valve, and very rarely sudden onset headache may be the presenting symptom of aseptic or viral meningitis [15].

INTRACRANIAL HAEMORRHAGE

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH): The single most important, although probably not the commonest, cause of sudden severe headache is SAH. SAH accounts for a little over 10% of patients presenting with sudden onset ‘thunder clap’ headache [15]. A minor bleed causing sudden headache may be the only warning of a subsequent severe and often fatal haemorrhage. If the haemorrhage also occurs into the parenchyma of the brain, there may be focal neurological symptoms. Patients often describe it as the worst headache of their life [16].

The headache of SAH is occipital or generalised and of sudden onset, reaching maximum severity within seconds. If the haemorrhage is of sufficient severity, there may be transient loss of consciousness or coma induced; this occurs in nearly 50% of patients [17]. There is severe nausea, vomiting, photophobia and neck stiffness from the moment of onset of the headache. Seizures may occur. The patient is obtunded and looks extremely ill. Photopsia is NOT a feature.

Clinical features do not always clearly distinguish other causes of headache from SAH [15, 18]. The presence or lack of accompanying symptoms like nausea, vomiting, photophobia and collapse at onset does not seem a reliable means of distinguishing between SAH and benign causes of acute headache [15].

In almost 20–40% of patients with SAH a warning leak (minor haemorrhage) may occur 1–8 weeks prior to a major SAH. The associated headache (referred to as a sentinel headache) is often short-lived and the patient may not seek immediate medical attention [19]. Even if the patient consults a physician the headache seems so trivial that often the diagnosis is missed [20]. Some of these patients are seen some days to weeks later [21] with the story of a sudden, explosive severe headache, usually in the absence of any other symptoms. The briefer the headache, the less likely it was related to a warning bleed. Here the question arises as to whether they have suffered a SAH and how extensively they should be investigated, and there is no easy answer to this question.

The probability of detecting an aneurysmal haemorrhage on CT scans performed at various intervals after the ictus is [9]:

The probability of detecting xanthochromia with spectrophotometry of the CSF at various times after a SAH is [9]:

Magnetic resonance angiography will detect aneurysms of > 3 mm in diameter and is recommended in patients with thunderclap headache with a low index of suspicion for SAH (normal CT scan and CSF) [9], as the risk of subsequent SAH is negligible [21, 22]. If the index of suspicion for SAH is high standard angiography should be performed.

A 3rd nerve palsy with a dilated pupil is a classic sign of a sentinel bleed.

Intracerebral haemorrhage: The headache of intracerebral haemorrhage is associated with nausea and vomiting due to raised intracranial pressure. It is often sudden in onset and of maximum severity at onset; however, it can increase in severity more slowly over a period of minutes to hours. In this situation the patient will usually have depression of the conscious state and often focal neurological signs.

Intraventricular haemorrhage: Primary intraventricular haemorrhage is rare and usually results from parenchymal (intracerebral) haemorrhage rupturing into the ventricle. The headache is of sudden onset and maximum intensity within seconds; it is usually associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia and neck rigidity. If the haemorrhage is more severe or if it leads to secondary hydrocephalus, depression of the conscious state will occur. There are no focal neurological symptoms unless the intraventricular haemorrhage is secondary to a parenchymal haemorrhage.

COUGH, BENIGN EXERTIONAL, BENIGN SEX, ICE-CREAM AND ICE-PICK HEADACHEs

Anybody who has suffered from a headache knows that coughing, sneezing or straining momentarily exacerbates the headache. Headache precipitated by coughing is referred to as cough headache. A similar headache can also be precipitated by anything that increases intrathoracic pressure such as sneezing, straining, laughing or stooping [24]. In the majority of patients with this headache, no structural pathology is present, although in as many as 25% it may be symptomatic (indicating the presence of an underlying pathology) with a significant proportion related to a Chiari malformation [25].

Cough headache: Benign cough headache is a headache precipitated by coughing in the absence of any intracranial disorder. The headache is of maximum severity at onset, coming on within seconds of coughing, sneezing or straining. It is very brief, lasting only a few seconds to less than a minute. There are no associated symptoms. The headache is generalised, frontal or occipital. The headaches usually resolve within 1 or 2 years although cases have been described lasting up to 12 years [26].

Exertional headache: Benign exertional headache is a bilateral, throbbing headache, lasting from 5 minutes to 24 hours specifically provoked by physical exercise and not associated with any systemic or intracranial disorder [28]. A small percentage of patients with exertional headache may have structural pathology [28]. This headache is of sudden onset (but not usually described as explosive in nature), generalised frontal or occipital and precipitated by activities such as weight lifting or any other activity that causes the patient to Valsalva. Similar to coital headache, there may be an antecedent dull occipital pain that builds up in severity over seconds to minutes as the intensity of the exercise increases and, if the person stops exerting themselves, this warning headache will resolve and they will not experience the sudden severe headache. The aetiology of this headache is unknown. Recurrent episodes may occur for weeks, occasionally months.

Benign sex (orgasmic or coital) headache: ‘Headache associated with sexual activity’ describes bilateral headaches precipitated by masturbation or coitus in the absence of any intracranial disorder [29, 30]. The headache is sudden in onset and excruciatingly severe, occurring at the moment of orgasm. It is predominantly occipital, but may be frontal or generalised. It is brief, lasting minutes, rarely hours. There are no associated symptoms. There is often a valuable clue that is not seen with SAH: the patient may experience a dull pain in the occipital or suboccipital region that increases in severity as excitement increases, subsides if they interrupt sexual activity and recurs if they become aroused again. If the patient interrupts sexual activity and avoids orgasm, this dull headache subsides without the subsequent severe explosive headache. If you can obtain a history of this headache preceding the sudden explosive headache, then the diagnosis is quite straightforward. On the other hand, if the history of this warning headache is not elicited, the major differential diagnosis, particularly if the headache lasts hours, is SAH. The aetiology of this headache is unclear but it is almost invariably seen in patients who are experiencing considerable stress in their lives and, once the stress resolves, so do the headaches.

Rarely, patients may experience their first SAH when coughing, sneezing, straining, exerting themselves or during sexual intercourse [25]. Here, although the headache will be explosive in onset, there will not be an antecedent warning headache in the seconds before the explosive headache, and the headache will persist for hours to days and is usually associated with nausea, vomiting, neck stiffness and possibly a focal neurological deficit and/or depression of the conscious state.

Ice-cream or cold-induced headache: Cold-induced headache occurs when the patient is eating or drinking something very cold such as ice cream that touches the palate or posterior pharyngeal wall. The patient experiences the onset over seconds of an excruciating, unilateral frontal headache that can be so severe that it may induce a profound bradycardia and syncope. This is a common cause of headache in adolescents [31] and is not influenced by eating ice cream more slowly [32].

Ice-pick headache: Ice-pick headache is also termed ‘jabs and jolts’ and refers to a curious entity in which the patient experiences recurrent, brief stabbing pains, often localised to one part of the head, rarely in other parts of the body. The patient describes the pain as lancinating like a needle, a nail or an ice pick being stabbed into their scalp. The pain lasts seconds only, may occur as a single jab of pain or there may be many stabs of pain within seconds to a minute. The commonest site is the temples. The same site on the opposite side (mirror image) of the head may be similarly affected. Ice-pick headaches occur more commonly in patients with migraine, where they can occur during or before the migraine [33]. They are benign and do not represent any sinister underlying pathology; reassurance is all that is required.

Aseptic or viral meningitis: Very rarely, aseptic or viral meningitis may present with the very abrupt onset of severe headache [15]. The associated fever and sweats and the presence of an antecedent upper respiratory tract infection provide clues to the possible diagnosis, but a lumbar puncture may be required to differentiate aseptic meningitis from SAH.

Posture-induced headache

POST-LUMBAR PUNCTURE HEADACHE

The characteristic and pathognomonic feature is a headache that worsens within 15 minutes of standing and resolves within 30 minutes if the patient lies completely flat [8], particularly if the foot of the bed or the legs are elevated. If the patient lies down on several pillows the headache will be less severe but will not be abolished. It is important that the headache resolves as all headaches are usually less severe when a patient lies down. The headache can be dull or throbbing, frontal, occipital or generalised, worsened by coughing, sneezing and straining, i.e. non-specific features.

The headache usually develops within 1 or 2 days of the lumbar puncture (LP) or epidural, although rare cases occurring 12 days later have been reported [34]. CSF pressures, by definition, are quite low and can be measured to confirm the diagnosis [35]. Although it usually resolves spontaneously, there are reports of it persisting for up to 19 months [36].

Post-LP headache occurs in as many as 30% of patients [37]. The incidence is reduced to as low as 5% when a smaller gauge needle is used, inserting the bevel parallel rather than at right angles to the fibres of the dura, the stylet is re-inserted before removing the needle or non-cutting (pencil-point) needles are used [38, 39]. There is no evidence that bedrest following an LP reduces the incidence of headache. The incidence is also not influenced by whether the LP is performed in the sitting or lying position or whether increased oral or IV fluids are administered. The volume of CSF removed does not increase the incidence of post-LP headache, thus there should be no hesitation in removing copious amounts of CSF for diagnostic purposes.

LOW-PRESSURE HEADACHE OR SPONTANEOUS INTRACRANIAL HYPOTENSION

The clinical features are identical to the headache seen after an LP. This headache relates to a leak of CSF either from the nose following a head injury (rarely a spontaneous leak) or, in the majority of patients, the leak is at the level of the spine, particularly the thoracic spine and cervicothoracic junction [35].

Headaches of gradual onset

CRANIAL ARTERITIS

Cranial arteritis (also known as giant cell or temporal arteritis as most often the temporal arteries are affected) is a vasculitis that distinctly targets large- and medium-sized arteries, preferentially the aorta and its extracranial branches, and in particular the temporal and occipital arteries [44]. This is a disorder of the older patient (the mean age is almost 75 [45]) and is rarely seen below the age of 50 [46]. It is more common in women and age-specific incidence rates increase with age [47]. Cranial arteritis should be treated as an emergency as a delay in diagnosis may lead to irreversible blindness due to ophthalmic artery occlusion.

• scalp tenderness (pain on brushing or washing the hair)

• jaw claudication (pain in the jaw with chewing)

• polymyalgia rheumatica (aches and pains in the shoulder region and often in the proximal legs, occurring in up to 50% of patients).

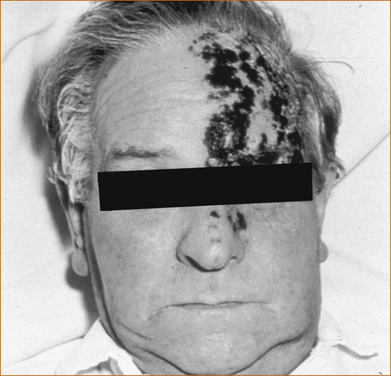

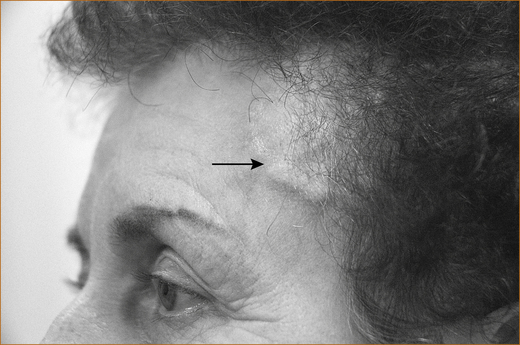

Occasionally the patient has prominent, tender thrombosed extracranial arteries (see Figure 9.4). Headache is not the only presentation of cranial arteritis: it can present with or be associated with anorexia, weight loss, joint pains, a fever of unknown origin, transient visual obscurations (lasting minutes or up to 2 hours), central retinal artery occlusion or anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy [AION] resulting in unilateral or even bilateral blindness [48–50]. Diplopia (double vision) that relates to ischaemia of the ocular muscles or nerves innervating those muscles has been described [48].

FIGURE 9.4 Prominent temporal arteries that are tender and non-pulsatile indicating thrombosis of the vessel

Investigation of suspected cranial arteritis: The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is invariably elevated as is the C-reactive protein (CRP), although early on both these tests may be normal. If cranial arteritis is suspected, repeated testing over the ensuing days and weeks is necessary. Biopsy of the temporal or occipital artery can be diagnostic, but it is important to remember that the disease process is not contiguous along the vessel and, unless a long segment of artery is obtained, the biopsy may be normal [51]. The diagnostic yield is higher with a minimum length of 1 cm [52].

ACUTE BACTERIAL OR VIRAL MENINGITIS

Isolated headache, particularly in the absence of fever, is unlikely to be due to meningitis.

In general, patients present with increasingly severe generalised headache developing over several hours or rarely days, either constant or throbbing in nature. Headache, fever and neck stiffness occur in more than 90% of patients [53]. Photophobia, nausea and vomiting, a change in mental status, seizures and focal neurological deficits may also occur. Worsening of headache with eye movement is a characteristic feature.

The clinical features of meningitis in its early stages can, however, often be non-specific and yet patients with fulminant meningitis, particularly meningococcal meningitis, may deteriorate rapidly over hours, so that it is important to have a high index of suspicion. Meningococcal meningitis and septicaemia are often associated with a petechial or purpuric rash [54].

Viral meningitis can be mild such that patients may not present in the early stages and, by the time they seek advice, the headache is already resolving.

RECURRENT HEADACHES

Migraine with aura, migraine without aura and aura without migraine headache

In the original International Headache Society classification [55], migraine was referred to as classical, common or migraine equivalents. In the revised criteria the classification was changed such that migraine with aura replaced classic migraine, common migraine became migraine without aura and migraine equivalents are referred to as aura without migraine headache [8].

When the subacute onset of headache is accompanied by photopsia (flashing lights), scotomata (patches of visual loss), nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia or paraesthesia, the most likely diagnosis is migraine with aura. However, migraine is not the only cause of such a constellation of symptoms. The simultaneous onset of headache, photopsia, nausea and vomiting can occur with vertebrobasilar ischaemia (see Chapter 10, ‘Cerebrovascular disease’).

It was long thought, based on the work of Wolff [56], that the aura was related to vasoconstriction of the intracranial vessels and the headache was due to dilatation of the extracranial vessels. Although unique changes in brain blood flow seen in patients during attacks of migraine with aura [57] have been replicated in animal experiments [58], a recent controversial [59] MRI study has failed to confirm any changes in cerebral blood flow during nitroglycerin-induced migraine [60]. Cortical spreading depression (CSD) of Leäo [61] is a short-lasting depolarisation wave heralded by a brief phase of excitation, which is immediately followed by prolonged nerve cell depression synchronous with a dramatic failure of brain ion homeostasis, efflux of excitatory amino acids from nerve cells and enhanced energy metabolism [58]. CSD is now widely recognised as the neurophysiological substrate of classical migraine aura and may be involved in migraines without a perceived aura as well [62]. CSD moves across the cortex at a rate of 3–5 mm/min. This slow spread of cortical depolarisation is reflected in the gradual evolution of the associated visual and other focal neurological symptoms that occur with migraine.

The more common varieties of migraine as classified by the International Headache Society are listed below [8].

MIGRAINE WITH AURA

An aura occurs in a little over one-third of patients and lasts on average 27 minutes, and the headache follows within approximately 10 minutes [63]. The characteristic feature is that there is a separation in time between each aspect of the aura; the visual, sensory and other focal neurological symptoms do not develop simultaneously. The visual and neurological symptoms evolve gradually with the initial symptoms disappearing or lessening in intensity or area affected as the later ones either commence or increase in severity.

VISUAL SYMPTOMS: A variety of visual symptoms may occur during the aura. Photopsia (flashing lights) consists of zigzag or jagged lines, bright spots or stars referred to as fortification spectra that may leave an area of impaired vision in the centre, ‘the scintillating scotoma’. Scotomata may occur in the absence of any fortification spectra, resulting in patchy areas of loss of vision replaced by greyness or blackness, and at times a contralateral hemianopia or even total blindness may occur.

SENSORY SYMPTOMS: The sensory symptoms, usually described as a tingling or numbness, commence in one part of the body (e.g. the hand) and gradually spread over 10–20 minutes to involve a greater area of the body, including the face. Usually by the time the sensory symptoms have reached the foot they are no longer present at the site where they originated. The sensory symptoms persist for seconds up to 20 minutes. They may be ipsilateral or contralateral to the headache [64].

The headache: The headache of migraine is more commonly unilateral and frontal but may be bilateral, occipital or generalised. In some patients the headache begins in the neck and radiates up to the head. Very rarely, migraine can affect predominantly the face, an entity referred to as lower-half headache. Ice-pick pains are common in patients with migraine [33]. The headache increases in severity over minutes to an hour or two (more rapidly than tension-type headache). A common misconception is that migraine headache is throbbing in character but this occurs in only 50% of patients; constant non-throbbing headache is equally as common. The headache of migraine is severe, lasting less than 4 hours in 27%, 4–24 hours in 40%, 1–2 days in 11% and more than 2 days in 22% of patients [65].

MIGRAINE WITHOUT AURA

This consists of recurrent moderate to severe unilateral, pulsating headaches lasting 4–72 hours, aggravated by routine physical activity and associated with mild nausea and/or photophobia and phonophobia. If one takes patients with classic migraine (migraine with aura) and carefully analyses the headache, there are three characteristic features that seem to occur in most patients.1 Patients with migraine typically retire to bed without headache and either:

• awake in the middle of the night or

• awake at their normal time the following morning with severe headache.

• The other characteristic is that the headache increases in severity over a short period, usually minutes up to 2 hours.

It is uncertain whether migraine with aura and migraine without aura are the same disorder as far as treatment is concerned [66].

AURA WITHOUT HEADACHE (MIGRAINE WITHOUT HEADACHE OR MIGRAINE EQUIVALENTS)

These are episodes of completely reversible visual and/or sensory symptoms with or without speech disturbance that develop gradually, lasting less than 60 minutes and without subsequent headache [67, 68]. In essence these patients experience the symptoms typical of the aura of migraine without subsequently developing a headache. When the symptoms have occurred in the past as the typical aura of a migraine headache, the diagnosis is not difficult. If this has not occurred it can be difficult to differentiate such symptoms from transient ischaemic attacks. As already stated, the clue to the diagnosis is that the first symptoms are showing signs of resolving before subsequent symptoms either appear or fully develop. If the neurological symptoms develop simultaneously or if the initial symptoms are not showing signs of resolving as the later symptoms are developing then, although this can very rarely occur in migraine, a diagnosis of cerebral ischaemia should be considered.

BASILAR ARTERY MIGRAINE

Basilar artery migraine is migraine headache with aura symptoms clearly originating from the brainstem and/or from both hemispheres simultaneously but without motor weakness. To the uninitiated these patients can be terrifying, presenting with altered conscious state, total blindness, visual hallucinations, photopsia, fortification spectra, vertigo, ataxia and perioral and peripheral tingling or numbness. The symptoms last from 2 to 45 minutes and are followed by a severe throbbing headache and vomiting lasting several hours [69]. Basilar artery migraine is more common in young females but fortunately the attacks are infrequent.

HEMIPLEGIC MIGRAINE

Migraine with aura associated with weakness is referred to as familial hemiplegic migraine if a first- or second-degree relative is also affected [70]. Hemiplegic migraine is extremely rare and this diagnosis should be made with caution and, in the first instance, probably by a neurologist. The unilateral motor symptoms of hemiplegic migraine differ from the more common forms of aura. There is no apparent spread of symptoms over the course of an hour and the duration of motor weakness is much greater than in the other aura types. Patients with hemiplegic migraine often have unilateral weakness for hours to days [71].

MENSTRUAL MIGRAINE

This is defined as attacks of migraine without aura in menstruating women occurring exclusively on day 1 (± 2 days) of menstruation in at least two out of three menstrual cycles and at no other times of the cycle. Menstrual migraine occurs during or after the time at which oestradiol and progesterone levels fall to their lowest [72, 73]. In some patients migraine occurs only at the time of menstruation; other patients experience migraines both at the time of menstruation and at other times during the cycle. In the latter patients the migraine related to menstruation may not necessarily have a hormonal basis.

PRINCIPLES OF TREATMENT OF MIGRAINE

The most appropriate treatment is to identify any precipitating factor and eliminate that element. Some patients are adamant that their migraine is precipitated by certain foods, and this is particularly observed in children [74, 75]. The commonest foods include cow’s milk, egg, chocolate, oranges and orange juice, wheat, cheese, artificial colourings and preservatives such as benzoic acid and tartrazine found in tinned, packet and junk food, while in others alcohol seems to be the offending agent. Elimination of the offending substance in theory should reduce the frequency of migraine. However, a careful study by McQueen et al [76] could not demonstrate any benefit from an elimination diet. Despite this, one encounters patients who are adamant that they have experienced fewer migraine headaches when they eliminated a particular substance from their diet.2 Treatment begins with a headache and diet diary and the selective avoidance of foods presumed to trigger attacks [74].

Non-pharmacological treatments are often advocated. Although psychological factors are important triggers of migraine, there are no controlled trials confirming psychological therapy is effective. Biofeedback/relaxation therapy is effective in some patients [77]. A meta-analysis of acupuncture as therapy concluded that there is weak evidence for efficacy [78]. Hypnotherapy is difficult to subject to randomised controlled trials, but one unblinded study claimed efficacy [79]. Some patients have claimed that their migraine is helped by a chiropractor or a naturopath performing neck manipulation but there is no objective evidence of benefit.

The pharmacological treatment of migraine is influenced by:

1. the frequency and the severity of the attacks

2. the patient’s willingness to accept the potential risk of side effects from drugs

3. whether vomiting occurs early during the migraine, thus preventing the use of oral therapy. In this latter circumstance subcutaneous, intravenous, sublingual, intranasal or rectal therapy will need to be employed.

There are a large number of drugs that may be used to treat the acute migraine or as prophylactic therapy [80]. These are likely to change over the ensuing years. As migraine is an unpredictable illness, only the results of randomised controlled trials should be used to decide what therapies are useful. Currently recommended therapies for both the individual migraine and for prophylaxis are detailed in Appendix D.

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias

Cluster headaches together with short-lasting, unilateral, neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) syndrome and paroxysmal hemicranias belong to a group of disorders that the International Headache Society classifies as trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias [8].

CLUSTER HEADACHE

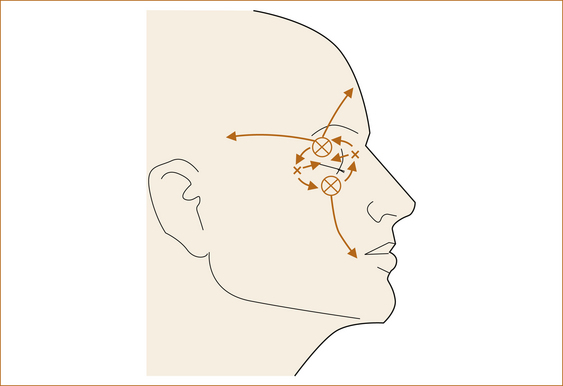

The pain of cluster headache must be strictly unilateral. It is almost invariably in or around the eye, although it may involve the temple, frontal or maxillary regions (see Figure 9.5). The pain increases in severity over minutes to an hour or so and is excruciatingly severe. The headaches last 15–180 minutes and occur every second day or up to eight times per day. There is often reddening and watering of the ipsilateral eye and blockage of the ipsilateral nostril. A transient Horner’s syndrome (see Figure 4.9) during the headache is virtually pathognomonic.

FIGURE 9.5 The distribution of pain seen with classic cluster headache Reproduced from Headache, 2nd edn, by NH Raskin, 1988, Churchill Livingstone, Figure 6.1, p 230 [3]

It is most often seen in men, and is also referred to as suicide headache because of the severity of the pain. When it does occur in women it is very similar, except that women experience more vomiting and other ‘migrainous symptoms’ [92].

Tension-type headache

The headache is typically bilateral, although it can be unilateral, and is often described as a tight sensation around the head or a pressure sensation in the head. Some authorities consider tension-type headache and migraine headache without associated features (common migraine) virtually indistinguishable, except that with migraine the headaches are relatively brief and episodic in nature [94]. Episodic tension-type headache is more likely to be seen in primary care practice [95] whereas chronic daily headache is more likely seen in the specialist clinic [96].

Many patients with the clinical features of tension-type headache take issue with the term ‘tension-type’, denying that there is tension or stress in their life. Some have commented that they could understand it if the headache had developed some time ago when there was considerable stress in their life, others deny any stress at all. The absence of stress should not preclude a diagnosis of tension-type headache if all other criteria are fulfilled. Similarly, the presence of stress in someone with headaches is only circumstantial evidence that the headaches are tension-type; it is important to use the diagnostic criteria for tension-type headache and look for the tension in a patient’s life to explain why they have tension-type headache. ‘Lifestyle headache’ is a term that patients are comfortable with and refers to the fact that they are experiencing a headache because of a lack of balance between the personal, professional and family aspects of their life.4

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is a very rare but commonly over-diagnosed cause of headache and facial pain. Of patients with either a self-diagnosis or physician diagnosis of sinusitis, 80% fulfil the International Headache Society migraine criteria [100, 101]. The problem is compounded by the fact that many patients’ sinuses have thickened mucosa and this is incorrectly interpreted as sinusitis. The presence of a fluid level in the sinus is required for the diagnosis of acute sinusitis.

Frontal or maxillary sinusitis usually presents with facial pain and both are discussed below. Ethmoid or sphenoid sinusitis presents with malaise, severe headache in the midline behind the nose and low-grade fever. The problem can be very difficult to diagnose if the ostium to the sinus is occluded as there will be no nasal discharge. The ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses are deep within the skull and therefore tenderness is not present. As the sinusitis progresses, pain usually increases over the ethmoidal area; however, the pain can be referred to the medial orbit, eye and brow. More severe cases of acute ethmoid sinusitis, especially in immune-compromised patients, can rapidly progress and present with facial cellulitis, orbital cellulitis and meningitis. Although it can have a bacterial, viral, fungal or allergic aetiology, it is most often bacterial.

Chronic headaches

Chronic daily headache is defined as headache on more than 15 days per month or 180 days per year. Approximately 35–40% of patients who seek treatment at headache centres suffer from daily or near-daily headache [102]. Some 80% of patients with chronic daily headache have evolved from episodic headache, predominantly migraine, and this is referred to as ‘transformed migraine’. In 20% of patients the headache is daily from onset [103].

Chronic daily headache may be constant or throbbing; mild, moderate or severe; and often is associated with mild photophobia, photophobia and nausea. Consistently unilateral headache is seen in only 2% of patients [104]. The headache fluctuates in severity from hour to hour and day to day. Patients retire with a headache and awaken with the headache the following morning.

Medication overuse syndrome is also referred to as rebound headache and is defined as the perpetuation of head pain in chronic headache sufferers, caused by frequent and excessive use of immediate relief medication. The International Headache Society [105] defines medication overuse headache as:

A headache that is present on ≥ 15 days/month fulfilling criteria C and D

B regular overuse for > 3 months of one or more drugs that can be taken for acute and/or symptomatic treatment of headache

C headache that has developed or markedly worsened during medication overuse

D headache that resolves or reverts to its previous pattern within 2 months after discontinuation of overused medication.

HEADACHE IN CHRONIC MENINGITIS

Chronic meningitis is defined as irritation and inflammation of the meninges persisting for more than 4 weeks and associated with pleocytosis (increased white cell count) in the CSF [107]. In reality, the average duration of symptoms varies from 17 to 43 months [108]. Chronic meningitis can be infective (cryptococcus, tuberculosis, listeria), non-infective (sarcoidosis, mollaret, drugs) or related to malignancy [109].

Low-grade fever, headache and mild neck stiffness may be extremely subtle and variable and any one feature may be absent. Mental status changes, seizures or focal deficits may evolve over time [110]. The headache can slowly worsen, fluctuate or remain static. The headache is bilateral, frontal and retro-orbital, and may be associated with photophobia, nausea and vomiting and generalised malaise. The presence of a fever suggests an infective aetiology and, although significant weight loss can occur with all causes, it is more common with malignancy. Night sweats, neck stiffness, papilloedema and possibly cranial nerve abnormalities have been described [111, 112].

HEADACHE AND IDIOPATHIC INTRACRANIAL HYPERTENSION

The headache is constant or throbbing, worse with coughing or straining (like most headaches) and may mimic chronic tension-type headache. The headache is generalised and of low to moderate severity. At times it can be pulsatile and awaken the patient from sleep. Retro-ocular pain worse with eye movement can occur [113]. The presence of visual obscurations (transient blindness lasting seconds) may occur, especially when straining. Bilateral papilloedema is the only sign unless the patient develops cranial nerve palsies (most commonly a 6th) secondary to the raised intracranial pressure.

WHEN TO WORRY

• headache awakening patients from sleep

• thunderclap onset of headache

• headaches associated with focal neurological symptoms that accompany or outlast the headache [114]

• long-lasting headaches (weeks or months) [114]

• headache with systemic symptoms such as anorexia, weight loss or fever, scalp tenderness or jaw claudication

Headache and brain tumours

Many patients with headache fear they have a brain tumour (see Figure 9.6). Fortunately these are very rare. Although headache is a common symptom of brain tumours, occurring in up to 70% of adults [115] and 60% of children [116], it is the sole manifestation in only 2% of patients [117]. In primary care, the risk of brain tumour with a headache presentation is less than 0.1% [10, 118]. This implies a primary care physician will have to do 1000 imaging procedures on patients with headache to detect one tumour!

Many of the features of the brain tumour-associated headache are non-specific. It is mild to moderately severe lasting for hours (not all day every day like chronic daily or tension-type headache) and develops over weeks or months [119]. Headache that awakens the patient from sleep and the presence of unsteadiness are the two main clinical features that should alert the clinician to the possibility of a brain tumour [115, 119]. Increasingly severe headache and the development of headache for the first time in elderly patients is also an indication of a possible brain tumour [120].

INVESTIGATING HEADACHE

The American Academy of Neurology practice guidelines [120] recommend imaging if the headache:

• is worsened by Valsalva manoeuvre

• causes the patient to awaken from sleep

• is a new headache in an older patient

• is a progressively worsening headache

• is accompanied by the presence of abnormal neurological findings.

The American Academy of Neurology guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence for choosing between a CT scan and an MRI scan, nor is there sufficient evidence to indicate whether an enhanced CT scan is better than an unenhanced CT scan when evaluating patients with migraine or other non-acute headaches [120]. Unfortunately most patients with headache are terrified that they have a brain tumour and virtually demand some form of imaging of the brain, and most have had a CT scan well before referral to the neurologist.

FACIAL PAIN

There are many causes of facial pain. The more common ones include:

Trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia consists of brief lancinating pain abrupt in onset and termination that MUST be within the distribution of the trigeminal nerve (see Figure 1.7), most often the 2nd and 3rd divisions and occasionally the 1st division. Although the paroxysms of pain may occur spontaneously, they are frequently precipitated by trivial stimuli such as washing, shaving, talking, brushing teeth, applying make-up or the wind blowing on the face.

Dental pain, which is discussed below, will also be in the distribution of the 2nd or 3rd divisions of the trigeminal nerve but never the 1st division. The two entities are very commonly confused [121]. Both dental pain and trigeminal neuralgia may be precipitated by eating or chewing but the vital clue that the problem is trigeminal neuralgia is the presence of a trigger point on the face, an area that if touched or sometimes even if the wind blows onto it will trigger a severe paroxysm of pain. The pain is so severe it makes the patient wince and hence the term ‘tic douloureux’, which is derived from the French meaning literally a painful tick.

In general, this is a condition of older patients and the aetiology is most often compression of the trigeminal nerve in the posterior fossa by an aberrant loop of a vessel [122]. Less commonly, it is symptomatic of another disorder, for example a tumour or multiple sclerosis. Younger age, bilateral trigeminal neuralgia and abnormal trigeminal sensation and corneal reflexes indicate a possible secondary cause [11].

Pain of dental origin

Pain of dental origin is at times very difficult to diagnose, particularly when it is related to a deep root abscess where often the dentist cannot see anything wrong with the tooth. The pain is a constant aching sensation, often fluctuating in severity and at times very distressing. The vital clue is that pain of dental origin is precipitated or exacerbated by contact of hot (and to a lesser extent cold) fluids on the affected tooth [123].

A useful bedside test is to put ice blocks in a glass of water and ask the patient to swirl the cold water around on the suspected side of the mouth. WARN the patient that this may cause a very severe attack of pain but it is a very effective way to sort out the problem. Start with the lower jaw and then the upper jaw. This may help localise the offending tooth as on occasion the pain is referred to the cheek when the problem is in the lower jaw.

Sinusitis

Acute sinusitis frequently follows upper respiratory tract infections. Although patients may complain of ipsilateral headache, ipsilateral facial pain over the region of the infected sinus is more common and usually associated with fever and purulent rhinorrhoea [124]. Clinical signs and symptoms most helpful in the diagnosis of maxillary and frontal sinusitis are the presence of a purulent nasal discharge, cough, purulent secretions observed on nasal examination and tenderness over the sinus [125].

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia

The pain of glossopharyngeal neuralgia is severe transient (seconds only) stabbing pain experienced in the ear, tonsillar fossa, base of the tongue or beneath the angle of the jaw. It is commonly provoked by coughing, swallowing or talking. In between paroxysms of pain there may be a dull discomfort. In some patients the pain is predominantly in the ear, in others it is in the pharynx. Unlike trigeminal neuralgia, the pain is beyond the distribution of the glossopharyngeal nerve also affecting the auricular and pharyngeal branches of the vagus nerve [126]. Occasionally, the pain is so severe that it results in transient asystole (no cardiac electrical activity) [127].

Persistent idiopathic facial pain

Persistent idiopathic facial pain was previously referred to as atypical facial pain. This consists of persistent facial pain that does not have the features of the cranial neuralgias and is not attributable to any other cause, i.e. does not fit a recognised pattern. The pain is deep, poorly localised, although most commonly it is in the region of the nasolabial fold or chin, and present most of the day almost every day. Occasionally, the condition follows surgery or trauma in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve [128]. There are no abnormal neurological signs and no cause is found despite detailed investigation, although occasional patients presenting with facial pain will have a nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The aetiology of this condition is unclear; some authorities suggest depression plays a significant role although this is controversial.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus and post-herpetic neuralgia

Facial pain, usually burning in nature and in the distribution of the 1st division of the trigeminal nerve, may precede the onset of the characteristic rash of herpes zoster by several days. Once the rash, consisting of blisters, appears the diagnosis is straightforward (see Figure 9.7). Post-herpetic neuralgia may develop in as many as 50% of patients (more commonly in the elderly) and pain may persist for months or even years after the rash has resolved. The pain is stabbing or burning in nature and the skin is very sensitive to touch (hyperaesthesia).

Tolosa–Hunt syndrome

Tolosa–Hunt syndrome is a rare disorder due to a granulomatous inflammatory process and is characterised by episodic orbital and periorbital pain, with paralysis of the 3rd, 4th or 6th cranial nerves developing within 2 weeks of the onset of pain. Occasionally, the 1st division of the 5th cranial nerve may be affected. It can remit spontaneously over days to weeks but may relapse and remit. There are many conditions that can produce a painful ophthalmoplegia, such as Graves’ disease, Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, diabetes and cavernous sinus thrombosis; aneurysm and lymphoma need to be excluded. An excellent discussion can be found in the review by Lutt et al [138].

The International Headache Society diagnostic criteria are:

• one or more episodes of unilateral orbital pain persisting for weeks if untreated

• paresis of the muscles of the eye, of one or more of the 3rd, 4th and/or 6th cranial nerves and/or demonstration of granulomas by MRI or biopsy

• paresis coinciding with the onset of pain or following it within 2 weeks

• pain and paresis resolving within 72 hours when treated adequately with corticosteroids

REFERENCES

1. Selby, G. Migraine and its variants. NSW: ADIS Health Science Press; 1983. [153].

2. Vinken P.J., Bruyn G.W., Klawans H.L., eds. Headache. Handbook of clinical neurology. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1986:556.

3. Raskin, N.H. Headache, 2nd edn. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. [396].

4. Lance, J.W., Goadsby, P.J. Mechanism and management of headache, 7th edn. New York: Elsevier; 2005.

5. Olesen, J., et al. The headaches, 3rd edn. London: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

6. You, J.J., et al. Indications for and results of outpatient computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in Ontario. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2008;59(3):135–143.

7. Jacob, J. Mechanisms of fever occurring in migraine. Adv Neurol. 1982;33:127–133.

8. Olsen, J., et al. The international classification of headache disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):1–160.

9. Evans, R.W. Diagnostic testing for the evaluation of headaches. Neurol Clin. 1996;14(1):1–26.

10. Rasmussen, B.K., Olesen, J. Symptomatic and nonsymptomatic headaches in a general population. Neurology. 1992;42(6):1225–1231.

11. Gronseth, G., et al. Practice parameter: The diagnostic evaluation and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Neurological Societies. Neurology. 2008;71(15):1183–1190.

12. Young, W.B., Rozen, T.D. Bilateral cluster headache: Case report and a theory of (failed) contralateral suppression. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(3):188–190.

13. Leone, M., Rigamonti, A., Bussone, G. Cluster headache sine headache: Two new cases in one family. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(1):12–14.

14. Rozen, T.D. Atypical presentations of cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(9):725–729.

15. Landtblom, A.M., et al. Sudden onset headache: A prospective study of features, incidence and causes. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(5):354–360.

16. Morgenstern, L.B., et al. Worst headache and subarachnoid hemorrhage: Prospective, modern computed tomography and spinal fluid analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32(3 Pt 1):297–304.

17. Bo, S.H., et al. Acute headache: A prospective diagnostic work-up of patients admitted to a general hospital. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(12):1293–1299.

18. Seet, C.M. Clinical presentation of patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage at a local emergency department. Singapore Med J. 1999;40(6):383–385.

19. Verweij, R.D., Wijdicks, E.F., van Gijn, J. Warning headache in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. A case-control study. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(9):1019–1020.

20. Jakobsson, K.E., et al. Warning leak and management outcome in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1996;85(6):995–999.

21. Markus, H.S. A prospective follow-up of thunderclap headache mimicking subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54(12):1117–1118.

22. Wijdicks, E.F., Kerkhoff, H., van Gijn, J. Long-term follow-up of 71 patients with thunderclap headache mimicking subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 1988;2(8602):68–70.

23. Qureshi, A.I., et al. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(19):1450–1460.

24. Symonds, C. Cough headache. Brain. 1956;79(4):557–568.

25. Pascual, J., et al. Cough, exertional, and sexual headaches: An analysis of 72 benign and symptomatic cases. Neurology. 1996;46(6):1520–1524.

26. Diamond, S., Medina, J.L. Prolonged benign exertional headache: Clinical characteristics and response to indomethacin. Adv Neurol. 1982;33:145–149.

27. Mathew, N.T. Indomethacin responsive headache syndromes. Headache. 1981;21(4):147–150.

28. Rooke, E.D. Benign exertional headache. Med Clin North Am. 1968;52(4):801–808.

29. Kriz, K. [Coitus as a factor in the pathogenesis of neurologic complications.]. Cesk Neurol. 1970;33(3):162–167.

30. Lance, J.W. Headaches occurring during sexual intercourse. Proc Aust Assoc Neurol. 1974;11:57–60.

31. Fuh, J.L., et al. Ice-cream headache – a large survey of 8359 adolescents. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(10):977–981.

32. Kaczorowski, M., Kaczorowski, J. Ice cream evoked headaches (ICE-H) study: Randomised trial of accelerated versus cautious ice cream eating regimen. BMJ. 2002;325(7378):1445–1446.

33. Raskin, N.H., Schwartz, R.K. Icepick-like pain. Neurology. 1980;30(2):203–205.

34. Reamy, B.V. Post-epidural headache: How late can it occur? J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(2):202–205.

35. Mokri, B. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2001;1(2):109–117.

36. Wilton, N.C., Globerson, J.H., de Rosayro, A.M. Epidural blood patch for postdural puncture headache: It’s never too late. Anesth Analg. 1986;65(8):895–896.

37. Thoennissen, J., et al. Does bed rest after cervical or lumbar puncture prevent headache? A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2001;165(10):1311–1316.

38. Evans, R.W., et al. Assessment: Prevention of post-lumbar puncture headaches: Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55(7):909–914.

39. Armon, C., Evans, R.W. Addendum to assessment: Prevention of post-lumbar puncture headaches. Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2005;65(4):510–512.

40. Moriyama, E., et al. Quantitative analysis of radioisotope cisternography in the diagnosis of intracranial hypotension. J Neurosurg. 2004;101(3):421–426.

41. Turnbull, D.K., Shepherd, D.B. Post-dural puncture headache: Pathogenesis, prevention and treatment. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91(5):718–729.

42. van Kooten, F., et al. Epidural blood patch in post dural puncture headache: A randomised, observer-blind, controlled clinical trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(5):553–558.

43. Ho, K.Y., Gan, T.J. Management of persistent post-dural puncture headache after repeated epidural blood patch. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51(5):633–636.

44. Schwedt, T.J., Dodick, D.W., Caselli, R.J. Giant cell arteritis. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2006;10(6):415–420.

45. Salvarani, C., et al. Reappraisal of the epidemiology of giant cell arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, over a fifty-year period. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(2):264–268.

46. Pipinos, I.I., et al. Giant-cell temporal arteritis in a 17-year-old male. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43(5):1053–1055.

47. Salvarani, C., et al. The incidence of giant cell arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota: apparent fluctuations in a cyclic pattern. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(3):192–194.

48. Danesh-Meyer, H.V., Savino, P.J. Giant cell arteritis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18(6):443–449.

49. Tal, S., Guller, V., Gurevich, A. Fever of unknown origin in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007;23(3):649–668,. [viii].

50. Schmidt, D. Ocular ichemia syndrome – a malignant course of giant cell arteritis. Eur J Med Res. 2005;10(6):233–242.

51. Tehrani, R., et al. Giant cell arteritis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2008;23(2):99–110.

52. Taylor-Gjevre, R., et al. Temporal artery biopsy for giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(7):1279–1282.

53. Roos, K.L. Acute bacterial meningitis. Semin Neurol. 2000;20(3):293–306.

54. Rosenstein, N.E., et al. Meningococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1378–1388.

55. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8(Suppl 7):1–96.

56. Wolff, H. Headache and other head pain, 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press; 1963.

57. Olesen, J., Larsen, B., Lauritzen, M. Focal hyperemia followed by spreading oligemia and impaired activation of rCBF in classic migraine. Ann Neurol. 1981;9(4):344–352.

58. Lauritzen, M. Pathophysiology of the migraine aura: The spreading depression theory. Brain. 1994;117(Pt 1):199–210.

59. VanDenBrink, A.M., Duncker, D.J., Saxena, P.R. Migraine headache is not associated with cerebral or meningeal vasodilatation – a 3T magnetic resonance angiography study. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 6):e112. [author reply e113].

60. Schoonman, G.G., et al. Migraine headache is not associated with cerebral or meningeal vasodilatation – a 3T magnetic resonance angiography study. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 8):2192–2200.

61. Leao, A.A.P. Spreading depression of activity in cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1944;7:359–390.

62. Ayata, C. Spreading depression: From serendipity to targeted therapy in migraine prophylaxis. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(10):1095–1114.

63. Kelman, L. The aura: A tertiary care study of 952 migraine patients. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(9):728–734.

64. Jensen, K., et al. Classic migraine: A prospective reporting of symptoms. Acta Neurol Scand. 1986;73:359–362.

65. Selby, G., Lance, J.W. Observations on 500 cases of migraine and allied vascular headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:23–32.

66. Welch, K.M. Drug therapy of migraine. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(20):1476–1483.

67. Fisher, C.M. Late-life migraine accompaniments as a cause of unexplained transient ischemic attacks. Can J Neurol Sci. 1980;7(1):9–17.

68. Kunkel, R.S. Acephalgic migraine. Headache. 1986;26(4):198–201.

69. Bickerstaff, E.R. The basilar artery and the migraine epilepsy syndrome. Proc R Soc Med. 1962;55:167–169.

70. Glista, G.G., Mellinger, J.F., Rooke, E.D. Familial hemiplegic migraine. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975;50(6):307–311.

71. Foroozan, R., Cutrer, F.M. Transient neurologic dysfunction in migraine. Neurol Clin. 2009;27(2):361–378.

72. Somerville, B.W. The role of progesterone in menstrual migraine. Neurology. 1971;21(8):853–859.

73. Somerville, B.W. The role of estradiol withdrawal in the etiology of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 1972;22(4):355–365.

74. Millichap, J.G., Yee, M.M. The diet factor in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;28(1):9–15.

75. Egger, J., et al. Is migraine food allergy? A double-blind controlled trial of oligoantigenic diet treatment. Lancet. 1983;2(8355):865–869.

76. McQueen, J., et al. A controlled trial of dietary modification in migraine. In: Rose F.C., ed. New advances in headache research. London: Smith-Gordon; 1989:235–242.

77. Holroyd, K.A., Penzien, D.B. Pharmacological versus non-pharmacological prophylaxis of recurrent migraine headache: A meta-analytic review of clinical trials. Pain. 1990;42(1):1–13.

78. Melchart, D., et al. Acupuncture for recurrent headaches: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(9):779–786. [discussion 765].

79. Anderson, J.A., Basker, M.A., Dalton, R. Migraine and hypnotherapy. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 1975;23(1):48–58.

80. Goadsby, P.J. Advances in the pharmacotherapy of migraine: How knowledge of pathophysiology is guiding drug development. Drugs R D. 1999;2(6):361–374.

81. Krymchantowski, A.V. Acute treatment of migraine: Breaking the paradigm of monotherapy. BMC Neurol. 2004;4:4.

82. Diener, H.C. Medication overuse is more than just taking too much. Cephalalgia. 2005;25(7):481.

83. Silberstein, S.D., et al. Botulinum toxin type A for the prophylactic treatment of chronic daily headache: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(9):1126–1137.

84. Mathew, N.T., et al. Botulinum toxin type A (BOTOX) for the prophylactic treatment of chronic daily headache: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache. 2005;45(4):293–307.

85. Aurora, S.K., et al. Botulinum toxin type A prophylactic treatment of episodic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled exploratory study. Headache. 2007;47(4):486–499.

86. Relja, M., et al. A multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group study of multiple treatments of botulinum toxin type A (BoNTA) for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine headaches. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(6):492–503.

87. Guyuron, B., et al. A placebo-controlled surgical trial of the treatment of migraine headaches. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):461–468.

88. Magos, A.L., Zilkha, K.J., Studd, J.W. Treatment of menstrual migraine by oestradiol implants. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1983;46(11):1044–1046.

89. Sances, G., et al. Naproxen sodium in menstrual migraine prophylaxis: A double-blind placebo controlled study. Headache. 1990;30(11):705–709.

90. Tuchman, M.M., et al. Oral zolmitriptan in the short-term prevention of menstrual migraine: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(10):877–886.

91. Mannix, L.K., et al. Combination treatment for menstrual migraine and dysmenorrhea using sumatriptan-naproxen: Two randomized controlled trials. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(1):106–113.

92. Rozen, T.D., et al. Cluster headache in women: clinical characteristics and comparison with cluster headache in men. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70(5):613–617.

93. May, A., et al. EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13(10):1066–1077.

94. Zeigler, A.K., Hassanein, R.T. Migraine muscle contraction headache dichotomy studied by statistical analysis of headache symptoms. In: Rose F.C., ed. Advances in migraine research and therapy. New York: Raven Press; 1995:7–11.

95. Rasmussen, B.K., et al. Epidemiology of headache in a general population – a prevalence study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44(11):1147–1157.

96. Lance, J.W., Curran, D.A. Treatment of chronic tension headache. Lancet. 1964;1(7345):1236–1239.

97. Lance, J.W., Goadsby, P.J. Mechanisms and Management of Headache, 7th edn. Elsevier, Butterworth, Heinemann; 2005.

98. Melis, P.M., et al. Treatment of chronic tension-type headache with hypnotherapy: a single-blind time controlled study. Headache. 1991;31(10):686–689.

99. Devineni, T., Blanchard, E.B. A randomized controlled trial of an internet-based treatment for chronic headache. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(3):277–292.

100. Blau, J.N. A note on migraine and the nose. Headache. 1988;28(7):495.

101. Schreiber, C.P., et al. Prevalence of migraine in patients with a history of self-reported or physician-diagnosed “sinus” headache. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(16):1769–1772.

102. Mathew, N.T., Reuveni, U., Perez, F. Transformed or evolutive migraine. Headache. 1987;27(2):102–106.

103. Mathew, N.T. Transformed migraine, analgesic rebound, and other chronic daily headaches. Neurol Clin. 1997;15(1):167–186.

104. Solomon, S., Lipton, R.B., Newman, L.C. Clinical features of chronic daily headache. Headache. 1992;32(7):325–329.

105. Silberstein, S.D., et al. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition (ICHD-II) – Revision of criteria for 8.2 Medication-overuse headache. Cephalalgia. 2005;25(6):460–465.

106. Kudrow, L. Paradoxical effects of frequent analgesic use. Adv Neurol. 1982;33:335–341.

107. Ellner, J.J., Bennett, J.E. Chronic meningitis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55(5):341–369.

108. Smith, J.E., Aksamit, A.J., Jr. Outcome of chronic idiopathic meningitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69(6):548–556.

109. Coyle, P.K. Overview of acute and chronic meningitis. Neurol Clin. 1999;17(4):691–710.

110. Helbok, R., et al. Chronic meningitis. J Neurol. 2009;256(2):168–175.

111. Anderson, N.E., Willoughby, W.E. Chronic meningitis without predisposing illness – a review of 83 cases. Q J Med. 1987;63(240):283–295.

112. Ginsberg, L., Kidd, D. Chronic and recurrent meningitis. Pract Neurol. 2008;8(6):348–361.

113. Wall, M. The headache profile of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Cephalalgia. 1990;10(6):331–335.

114. Schoenen, J., Sandor, P.S. Headache with focal neurological signs or symptoms: A complicated differential diagnosis. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(4):237–245.

115. Suwanwela, N., Phanthumchinda, K., Kaoropthum, S. Headache in brain tumor: A cross-sectional study. Headache. 1994;34(7):435–438.

116. The Childhood Brain Tumor Consortium. The epidemiology of headache among children with brain tumor. Headache in children with brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 1991;10(1):31–46.

117. Schankin, C.J., et al. Characteristics of brain tumour-associated headache. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(8):904–911.

118. Hamilton, W., Kernick, D. Clinical features of primary brain tumours: a case-control study using electronic primary care records. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(542):695–699.

119. Pfund, Z., et al. Headache in intracranial tumors. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(9):787–790. [discussion 765].

120. American Academy of Neurology. Report of the Quality Standards Sub-Committee of the American Academy of Neurology. The utility of neuro imaging in the evaluation of headache in patients with normal neurological examinations. 2008. Available: www.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/gl0088.pdf (17 Apr 2009).

121. Tew, J.M.J., Loveren, H. Percutaneous rhizotomy in the treatment of intractable facial pain (trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, and vagal nerves). In: Schmidek H.H., Sweet W.H., eds. Operative neurosurgical techniques: Indications, methods, and results. 2nd edn. Orlando: Grune & Stratton; 1998:1111–1123.

122. Jannetta, P.J. Arterial compression of the trigeminal nerve at the pons in patients with trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1967;26(1 Suppl):159–162.

123. Heir, G.M. Facial pain of dental origin – a review for physicians. Headache. 1987;27(10):540–547.

124. Evans, K.L. Recognition and management of sinusitis. Drugs. 1998;56(1):59–71.

125. Diaz, I., Bamberger, D.M. Acute sinusitis. Semin Respir Infect. 1995;10(1):14–20.

126. Rushton, J.G., Stevens, J.C., Miller, R.H. Glossopharyngeal (vagoglossopharyngeal) neuralgia: A study of 217 cases. Arch Neurol. 1981;38(4):201–205.

127. Bruyn, G.W. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia. In: Vincken P.J., Bruyn G.W., Klawans H.L., eds. Handbook of clinical neurology. Headache. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1986:487–494.

128. Siccoli, M.M., Bassetti, C.L., Sandor, P.S. Facial pain: Clinical differential diagnosis. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(3):257–267.

129. Lascelles, R.G. Atypical facial pain and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1966;112(488):651–659.

130. Feinmann, C., Harris, M., Cawley, R. Psychogenic facial pain: presentation and treatment. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288(6415):436–438.

131. Oxman, M.N., et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(22):2271–2284.

132. Harpaz, R., Ortega-Sanchez, I.R., Seward, J.F. Prevention of herpes zoster: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-5):1–30. [quiz CE2–4].

133. Wood, M.J., et al. Oral acyclovir therapy accelerates pain resolution in patients with herpes zoster: A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(2):341–347.

134. Bowsher, D. The effects of pre-emptive treatment of postherpetic neuralgia with amitriptyline: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(6):327–331.

135. Eaglstein, W.H., Katz, R., Brown, J.A. The effects of early corticosteroid therapy on the skin eruption and pain of herpes zoster. JAMA. 1970;211(10):1681–1683.

136. Keczkes, K., Basheer, A.M. Do corticosteroids prevent post-herpetic neuralgia? Br J Dermatol. 1980;102(5):551–555.

137. He, L., et al. Corticosteroids for preventing postherpetic neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:1. [CD005582].

138. Lutt, J.R., et al. Orbital inflammatory disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37(4):207–222.

139. Pascual, J., et al. Tolosa–Hunt syndrome: Focus on MRI diagnosis. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(Suppl 25):36–38.

140. Kline, L.B., Hoyt, W.F. The Tolosa–Hunt syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(5):577–582.

1Personal unpublished and unproven observations.

4Personal unpublished and unproven observations. These patients have not found a balance between time for themselves, time for their work and time for their families. Many of these patients’ headaches have resolved once they resume the physical or social activity that they have given up because they had become too busy.