101 Headache

• Inquire about the onset, quality, severity, associated symptoms, and past history of the headache; a new headache that is due to a serious “cannot miss” cause will usually have unique features.

• The most frequently missed components of the neurologic examination are visual fields and gait; they are helpful in the diagnosis of subtle disorders.

• New abnormal neurologic findings must be evaluated and explained.

• Patients whose headaches are abrupt, with maximal intensity at or close to onset (“thunderclap” headaches), should be evaluated for subarachnoid hemorrhage even if the findings on neurologic examination are entirely normal.

• When evaluating for a nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, a negative computed tomography scan should be followed by a lumbar puncture.

Pathophysiology

The sensation of headache is rarely due to injury to the brain parenchyma itself. Rather, head pain results from tension, traction, distention, dilation, or inflammation of pain-sensitive structures external to the skull, portions of the dura mater, and blood vessels. Each of these mechanisms is probably mediated by a final common biochemical pathway that results in pain; therefore, a favorable response to analgesics should not be used to judge the cause of an individual headache.1

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

EPs should develop a logical, practical, and accurate approach to identification of patients with serious pathology. A comprehensive organizational scheme developed by the International Headache Society has recently been updated (Table 101.1); however, this scheme is cumbersome in emergency practice. For practical purposes, headaches can be divided into “benign” and “cannot miss” categories (Table 101.2).

Table 101.1 International Headache Society Classification of Headaches

| HEADACHE ASSOCIATED WITH | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Migraine | Requires 5 or more attacks of a specific nature lasting 4-72 hr. Can be unilateral, pulsating, moderate, or severe in intensity; aggravated by physical activity; or associated with nausea, vomiting, or photophobia |

| Tension type | Requires 10 or more attacks of a specific nature lasting 30 min to 7 days; absence of nausea, vomiting, and photophobia |

| Cluster type | Requires 5 or more attacks of a specific nature lasting 15-180 min; always unilateral; associated with eye, nose, or face symptoms |

| Other primary headaches | Includes a variety of brief (idiopathic stabbing headache) and situational (cough, exertional, coital) headache syndromes |

| Head trauma | Includes minor postinjury headaches |

| Vascular disorders | Includes cerebral ischemia and infarction, all forms of intracranial hemorrhage, venous sinus thrombosis, giant cell arteritis, arterial dissections |

| Nonvascular intracranial disorders | Includes idiopathic intracranial hypertension, post–lumbar puncture headache, tumor |

| Substance abuse or withdrawal | Includes drugs and food additives (e.g., monosodium glutamate headache, or Chinese restaurant syndrome); also includes headache from carbon monoxide poisoning |

| Infections | Includes headaches secondary to intracranial (meningitis, abscess) or extracranial infection |

| Disorders of homeostasis | Includes headaches secondary to hypercapnia, high-altitude illness, hypertensive encephalopathy, preeclampsia |

| HEENT (head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat) disorders (includes dental) | Includes narrow angle-closure glaucoma, sinusitis, temporomandibular joint disorder |

| Cranial neuralgias, nerve trunk and deafferentation pain | Most of these are cranial neuropathies or associated with herpes zoster |

From Olesen J. International Classification of Headache Disorders, Second Edition (ICHD-2): current status and future revisions. Cephalalgia 2006;26:1409–10.

Table 101.2 “Cannot Miss” Diagnoses

| DIAGNOSIS | SUGGESTIVE HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS | DIAGNOSTIC TESTING |

|---|---|---|

| Meningitis and encephalitis | Fever, stiff neck, accentuation by jolts, altered mental status, seizure | LP; if preceded by CT, administer antibiotics before CT |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage* | Abrupt onset of severe headache, stiff neck, third nerve palsy | CT scan; LP if CT is not diagnostic |

| Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) | Abrupt onset and focal neurologic deficit conforming to an arterial territory | CT scan; if available, MRI will give more information (should not delay thrombolytic therapy) |

| Dissection of craniocervical arteries | Neck pain, abrupt onset, variable presence of neurologic deficit | CT angiography, MRA, or conventional angiography |

| Hypertensive encephalopathy | Severe (usually chronic) hypertension; often papilledema and other signs of end-organ damage | Careful, titratable lowering of blood pressure by ≈25% of the peak level will decrease the headache |

| Idiopathic intracranial hypertension | Obese, female patient; papilledema; often sixth nerve palsy | LP (following an imaging study, which by definition will be normal) |

| Giant cell arteritis | Nearly always age > 50 yr, symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica, abnormal scalp vessels | ESR, temporal artery biopsy |

| Acute angle–closure glaucoma | Painful red eye with midposition pupil and corneal edema | Tonometry |

| Intracranial mass (tumor, abscess, hematoma)† | Any focal or generalized neurologic finding | CT scan; if available, MRI will provide more information |

| Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis | Hypercoagulable state of any type | MRI and MRA with venous phase, CT with venous phase |

| Carbon monoxide poisoning | Cluster of cases, winter season | COHb level |

| Pituitary apoplexy | Visual acuity or field abnormalities | MRI |

| Known pituitary tumor |

COHb, Carboxyhemoglobin; CT, computed tomography; LP, lumbar puncture; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Past and Family History

Predisposing factors for a secondary cause of headache should be determined. For example, poorly treated hypertension may lead to hypertensive encephalopathy, vascular risk factors can result in stroke, and a past or family history of cerebral aneurysm increases the likelihood of subarachnoid hemorrhage (Box 101.1).

Physical Examination

The physical examination (Box 101.2) is critical in guiding the differential diagnosis and appropriate work-up.

Box 101.2 Critical Features (Potential Diagnoses) of the Physical Examination

Neurologic Examination

Change in mental status (increased intracranial pressure, infection, carbon monoxide poisoning)

Decreased visual acuity (giant cell arteritis, acute angle–closure glaucoma)

Visual field cut (mass lesion, pituitary apoplexy)

Third nerve palsy (subarachnoid hemorrhage, cavernous sinus thrombosis)

Sixth nerve palsy (increased or decreased intracranial pressure, basilar meningitis)

Direction-changing nystagmus (cerebellar or brainstem stroke)

Lower motor neuron seventh nerve palsy (Bell palsy, Ramsay Hunt syndrome)

Eighth nerve palsy (diminished hearing or vertigo, Ramsay Hunt syndrome)

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Computed Tomography

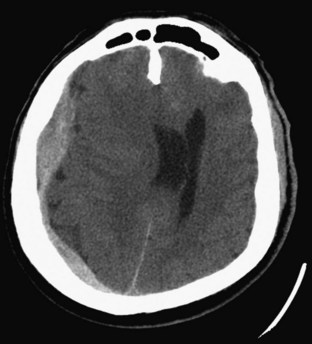

Computed tomography (CT) is often the first neuroimaging test because it is both rapid and widely available. A non–contrast-enhanced CT scan is extremely sensitive for acute intraparenchymal bleeding and very sensitive for subarachnoid bleeding (Fig. 101.1), but small or less acute subarachnoid bleeding may not be visible. Although some small tumors and abscesses are not visible on a non–contrast-enhanced scan, some abnormal finding will usually be seen on such scans in patients with masses large enough to cause a significant headache or focal neurologic findings (Fig. 101.2). Any focal neurologic signs or symptoms should be conveyed to the radiologist reading the CT scan so that appropriate attention can be directed to the anatomic site in question.

Which patients require CT scanning is a matter of some debate. Hard and fast rules do not exist, but in general, high-risk factors indicate the need for CT (Box 101.3). The American College of Emergency Physicians has a clinical policy about the use of CT in some situations.2

The type of CT to perform depends on the specific differential diagnosis under consideration. Imaging of a mass or an abscess can be improved with intravenous infusion of a contrast agent. CT angiography (CTA) can be performed with multidetector scanners. Depending on the number of detectors, the software, and the skill of the neuroradiologist, CTA can approach conventional angiography in direct visualization of the cerebral vasculature. For patients in whom an arteriovenous malformation or aneurysm is suspected, CTA is a useful modality, although the standard diagnostic algorithm is still CT followed by LP.2–4 CT venography can be useful in the diagnosis of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

Lumbar Puncture

LP remains an important diagnostic tool for headache patients. In patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage, the EP must be aware that CT scanning may be nondiagnostic and that LP is the next step necessary.2

Treatment

For patients with signs or symptoms of acute bacterial meningitis, a critical early decision is whether to perform a CT scan or proceed directly to LP (Box 101.4). Administration of antibiotics should not be delayed in patients who have signs of acute meningitis. Performing LP directly in an alert, neurologically intact patient with no medical history is usually safe, especially in those with normal venous pulsations on funduscopy.

Box 101.4 Patient Features Suggesting That Computed Tomography Be Performed Before Lumbar Puncture

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Treat pain early and adequately. The response to pain should not affect the work-up, so there is no reason to withhold appropriate analgesia.

Patients with hemophilia and headache require coagulation factor repletion on an emergency basis, sometimes even before head computed tomography, given their high risk for intracranial hemorrhage.

Patients with signs and symptoms of acute bacterial meningitis require early antibiotics, even if the diagnosis is not yet established.

Blood Pressure

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

Data to guide BP management in patients with intraparenchymal hemorrhage are limited, and no trial has demonstrated improved outcomes with reduction in BP. The American Heart Association published updated guidelines in 2010.5 There has been a trend away from nitroprusside and toward nicardipine and labetalol.

The 2010 guidelines state the following:

1. If systolic BP is higher than 200 mm Hg (MAP > 150), aggressive reduction with continuous intravenous medication and monitoring of BP every 5 minutes should be considered.

2a. If systolic BP is higher than 180 mm Hg (MAP > 130) AND ICP is possibly increased, monitoring ICP and reducing BP to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure higher than 60 should be considered.

2b. If systolic BP is higher than 180 mm Hg (MAP > 130) with NO increased ICP, modest reduction (target of 160/90 or MAP of 110) and monitoring every 15 minutes should be considered.

3. In patients with a systolic BP of 150 to 220 mm Hg, acute lowering to 140 systolic is “probably safe.”

Acute Angle–Closure Glaucoma

1. Acetazolamide, 500 mg intravenously followed by 500 mg orally

2. Timolol, 0.25% to 0.5% applied topically

3. Prednisolone, 1 to 2 drops onto the affected eye

4. Pilocarpine, 2% applied topically

5. Isosorbide, 1.5 g/kg orally, or glycerin, 1 to 2 g/kg orally

6. Mannitol, 1.5 to 2 g/kg intravenously

Migraine Headache

Box 101.5 summarizes the various agents that are useful in the management of acute migraine. Although opiates are used frequently in the ED, they should not be first-line treatment and should be reserved for rescue therapy in patients who do not respond to the initial medications—and even in this situation they should be used sparingly.

Box 101.5 Management of Moderate to Severe Acute Migraine Headaches

Antiemetics (first-line agents)—often combined with diphenhydramine; consider using both to prevent akathisia

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (first-line agents)—use in combination with antiemetics

Analgesics (first-line agents)—use in combination with antiemetics

5-HT1 receptor agonists—use in combination with antiemetics, analgesics

Steroids—no clear benefit acutely but may decrease recurrence

Cluster Headache

Cluster headache is typically a severe unilateral headache that can be accompanied by conjunctival injection, lacrimation, ptosis, miosis, rhinorrhea, and nasal congestion. Attacks can occur up to eight times a day and are severe but short-lived; the autonomic symptoms are typically unilateral and ipsilateral to the pain. Recognition is important because this headache subtype is uniquely sensitive to oxygen. Mainstays of emergency management include administration of oxygen and subcutaneous sumatriptan (Box 101.6).

Tension Headache

Tension headache is usually characterized by throbbing pain that radiates bilaterally from front to back and to the neck muscles. As with migraine headaches, one cannot firmly diagnose tension headache after a single episode, and this diagnosis requires more than nine previous episodes. Pain control consists of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, antiemetics, and perhaps caffeine (Box 101.7). Butalbital-containing agents (as with migraine headaches) may be used with caution, given the risk for dependency and rebound headache.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Documentation

Documentation

The history in every headache patient should include the onset, timing, severity, comparison with previous headaches, and any new neurologic complaints.

The physical examination should include a complete neurologic and head, eye, ear, nose, and throat examination. Any new neurologic findings must be explained.

Visual fields and gait assessment cover a wide range of neuroanatomic territory and are often either inadequately tested or inadequately documented.

Be very careful assigning the diagnosis of migraine headache to patients if they do not already have this diagnosis or if the current headache is different from their usual migraines.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Complications and Pitfalls

Just because a patient states that he or she has had “migraine” (or “tension” or “sinus”) headaches does not mean that the headaches ever formally met these criteria or have ever been evaluated or that this headache is the same as the previous headaches. This is especially true for recent-onset headaches.

If head computed tomography is performed to evaluate for subarachnoid hemorrhage, it should always be followed by lumbar puncture to evaluate for xanthochromia and the presence of blood.

Visualization of mucosal thickening in the paranasal sinuses on computed tomography is a common incidental finding and should not be used to diagnose acute sinusitis.

A favorable response to analgesics has little or no diagnostic significance and should not be used to exclude a secondary cause of headache.

2010 Antihypertensive treatment of acute cerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:637–648.

Anderson CS, Huang Y, Arima H, et al. Effects of early intensive blood pressure–lowering treatment on the growth of hematoma and perihematomal edema in acute intracerebral hemorrhage: the Intensive Blood Pressure Reduction in Acute Cerebral Haemorrhage Trial (INTERACT). Stroke. 2010;41:307–312.

Baraff LJ, Byyny RL, Probst MA, et al. Prevalence of herniation and intracranial shift on cranial tomography in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage and a normal neurologic examination. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:423–428.

Bederson JB, Awad IA, Wiebers DO, et al. Recommendations for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000;102:2300–2308.

Bederson JB, Connolly ES, Jr., Batjer HH, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40:994–1025.

Boesiger BM, Shiber JR. Subarachnoid hemorrhage diagnosis by computed tomography and lumbar puncture: are fifth generation CT scanners better at identifying subarachnoid hemorrhage? J Emerg Med. 2005;29:23–27.

Byyny RL, Mower WR, Shum N, et al. Sensitivity of noncontrast cranial computed tomography for the emergency department diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:697–703.

Carstairs SD, Tanen DA, Duncan TD, et al. Computed tomographic angiography for the evaluation of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:486–492.

Cheung CS, Mak PS, Manley KV, et al. Predictors of important neurological causes of dizziness among patients presenting to the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2010;27:517–521.

Cortnum S, Sorensen P, Jorgensen J. Determining the sensitivity of computed tomography scanning in early detection of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:900–902. discussion 903

De Luca GC, Bartleson JD. When and how to investigate the patient with headache. Semin Neurol. 2010;30:131–144.

Edlow JA. Diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage—are we doing better [editorial]? Stroke. 2007;38:1129–1131.

Edlow JA. Diagnosing headache in the emergency department: what is more important? Being right, or not being wrong? Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:1257–1258.

Edlow JA. What are the unintended consequences of changing the diagnostic paradigm for subarachnoid hemorrhage after brain computed tomography to computed tomographic angiography in place of lumbar puncture? Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:991–995. discussion 996–997

Edlow JA, Caplan LR. Avoiding pitfalls in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:29–36.

Edlow JA, Malek AM, Ogilvy CS. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: update for emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2008;34:237–251.

Edlow JA, Panagos PD, Godwin SA, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with acute headache. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:407–436.

Eggers C, Liu W, Brinker G, et al. Do negative CCT and CSF findings exclude a subarachnoid haemorrhage? A retrospective analysis of 220 patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:300–305.

Fischer C, Goldstein J, Edlow J. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in the emergency department: retrospective analysis of 17 cases and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:140–147.

Friedman BW, Solorzano C, Esses D, et al. Treating headache recurrence after emergency department discharge: a randomized controlled trial of naproxen versus sumatriptan. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:7–17.

Goldstein JN, Camargo CA, Jr., Pelletier AJ, et al. Headache in United States emergency departments: demographics, work-up and frequency of pathological diagnoses. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:684–690.

Johansson A, Lagerstedt K, Asplund K. Mishaps in the management of stroke: a review of 214 complaints to a medical responsibility board. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18:16–21.

Kelly AM, Walcynski T, Gunn B. The relative efficacy of phenothiazines for the treatment of acute migraine: a meta-analysis. Headache. 2009;49:1324–1332.

Kostic MA, Gutierrez FJ, Rieg TS, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of intravenous prochlorperazine versus subcutaneous sumatriptan in acute migraine therapy in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med.. 2010;56:1–6.

Landtblom AM, Fridriksson S, Boivie J, et al. Sudden onset headache: a prospective study of features, incidence and causes. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:354–360.

Linn F, Rinkel G, Algra A, et al. Headache characteristics in subarachnoid hemorrhage and benign thunderclap headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:791–793.

Linn FH, Voorbij HA, Rinkel GJ, et al. Visual inspection versus spectrophotometry in detecting bilirubin in cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1452–1454.

Linn FH, Wijdicks EF. Causes and management of thunderclap headache: a comprehensive review. Neurologist. 2002;8:279–289.

McCormack RF, Hutson A. Can computed tomography angiography of the brain replace lumbar puncture in the evaluation of acute-onset headache after a negative noncontrast cranial computed tomography scan? Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:444–451.

Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC, 3rd., Anderson C, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2010;41:2108–2129.

Perry JJ, Sivilotti ML, Stiell IG, et al. Should spectrophotometry be used to identify xanthochromia in the cerebrospinal fluid of alert patients suspected of having subarachnoid hemorrhage? Stroke. 2006;37:2467–2472.

Perry JJ, Spacek A, Forbes M, et al. Is the combination of negative computed tomography result and negative lumbar puncture result sufficient to rule out subarachnoid hemorrhage? Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:707–713.

Perry JJ, Stiell IG, Sivilotti ML, et al. High risk clinical characteristics for subarachnoid haemorrhage in patients with acute headache: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c5204.

Pope JV, Edlow JA. Favorable response to analgesics does not predict a benign etiology of headache. Headache. 2008;48:944–950.

Provenzale JM. Imaging evaluation of the patient with worst headache of life—it’s not all subarachnoid hemorrhage. Emerg Radiol. 2010;17:403–412.

Ramirez-Lassepas M, Espinosa CE, Cicero JJ, et al. Predictors of intracranial pathologic findings in patients who seek emergency care because of headache. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:1506–1509.

Raps EC, Rogers JD, Galetta SL, et al. The clinical spectrum of unruptured intracranial aneurysm. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:265–268.

Robertson CE, Black DF, Swanson JW. Management of migraine headache in the emergency department. Semin Neurol. 2010;30:201–211.

Savitz SI, Edlow J. Thunderclap headache with normal CT and lumbar puncture: further investigations are unnecessary. Stroke. 2008;39:1392–1393.

Savitz SI, Levitan EB, Wears R, et al. Pooled analysis of patients with thunderclap headache evaluated by CT and LP: is angiography necessary in patients with negative evaluations? J Neurol Sci. 2009;276:123–125.

Singh A, Alter HJ, Zaia B. Does the addition of dexamethasone to standard therapy for acute migraine headache decrease the incidence of recurrent headache for patients treated in the emergency department? A meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1223–1233.

Swadron SP. Pitfalls in the management of headache in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:127–147. viii–ix

1 Pope JV, Edlow JA. Favorable response to analgesics does not predict a benign etiology of headache. Headache. 2008;48:944–950.

2 Edlow JA, Panagos PD, Godwin SA, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with acute headache. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:407–436.

3 Edlow JA. What are the unintended consequences of changing the diagnostic paradigm for subarachnoid hemorrhage after brain computed tomography to computed tomographic angiography in place of lumbar puncture? Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:991–995. discussion 996–997

4 Savitz SI, Levitan EB, Wears R, et al. Pooled analysis of patients with thunderclap headache evaluated by CT and LP: is angiography necessary in patients with negative evaluations? J Neurol Sci. 2009;276:123–125.

5 Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC, 3rd., Anderson C, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2010;41:2108–2129.