Chapter 71 Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Definition of the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

The head-up tilt-table test (HUTT) is simply a method of subjecting patients to a prolonged upright position. It provokes a range of normal and abnormal responses and is used most commonly to investigate syncope. Tilt tests induce syncope or presyncope in most patients with otherwise undiagnosed syncope and induce the same endpoints in only a minority of control subjects.1 HUTTs have been used in diagnostic studies in populations such as those with neurally mediated syncope (NMS2; “reflex fainting”), syncope in the setting of structural heart disease, and loss of consciousness that might be caused by epilepsy. These tests are also used for the assessment of orthostatic hypotension, autonomic neuropathy, and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.2 They have been used as entry criteria in observational studies and clinical trials, mechanistic physiological studies of the neurally mediated reflex, and in pharmacologic treatment studies and have been proposed to be useful for selecting efficacious treatment.3,4 Tilt tests have made the informed care of syncope patients more accessible and less daunting. By their ability to induce syncope under controlled conditions, they have reassured many patients about a relatively benign diagnosis.

Indications for the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Syncope is a common problem. Community-based epidemiologic studies have shown that the lifetime prevalence of syncope is over 40% and that many people experience recurrent episodes of fainting.5 The neurally mediated (vasovagal) reflex is the most common cause, particularly in young people, but other causes are also frequently seen. Syncope is responsible for about 1% of emergency room visits and 1% to 3% of hospital admissions, and syncope patients are frequently referred to internists, cardiologists, and neurologists.6 A diagnostic process with reasonably high accuracy was needed to discriminate syncope caused by potentially fatal conditions from syncope caused by more benign ones. In the late 1980s, a number of groups reported the usefulness of the HUTT in diagnosing the particularly common neurally mediated reflex, which is the cause of NMS.7,8 Tilt tests are now widely used for diagnosing syncope, and they have been used as tools for physiological studies, for predicting outcome, and for selecting therapies.

Tilt testing is not the only diagnostic modality that is used for investigating the cause of syncope. Quantitative histories and implantable loop recorders are also under active investigation and are used in clinical practice. The uses of a focused syncope history, tilt tests, and loop recorders are all recommended in clinical guidelines.2 The cause of syncope can be comfortably determined with a good history in most cases, and the need to proceed with tilt testing or loop recorders should be determined on a case-by-case basis. Commonly, tilt tests are used if a clinical suspicion of some form of autonomic disorder such as NMS or an autonomic neuropathy is present, and loop recorders are indicated for a suspected arrhythmia.

Protocols and Procedures of the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

The core of the HUTT is passive head-upright tilt for 20 to 60 minutes until hypotension, bradycardia, and presyncope or syncope ensues or until the test ends. Variants of this method include the use of intravenous isoproterenol, sublingual nitrates, intravenous clomipramine, or combined lower-body negative pressure to induce an endpoint either earlier or with higher likelihood.9–13 Consensus conferences have recommended different uniform protocols, but no formal comparison of their diagnostic accuracies has been made.2 Protocols that use a steeper tilt angle or a longer duration of tilt and drug interventions have higher positive yields and lower specificities.

An example of the tilt testing equipment and protocols at one hospital is outlined in Table 71-1. Patients are studied either after overnight fasting or at least 2 hours after food absorption to decrease the risk of vomiting and aspiration. The patient is placed on a table (that has a footboard), which can rapidly and smoothly incline from a supine position to head-up tilt (between 60 and 80 degrees from baseline) and, more importantly, can rapidly return to the supine position in the event of hypotension or unconsciousness. Restraints are applied to the patient to avoid accidental falls during loss of consciousness. Some centers, but not all, routinely insert an intravenous catheter (after starting electrocardiogram [ECG] monitoring). This allows administration of medications, either for provocation (isoproterenol, nitroglycerin, or clomipramine) or rarely for rescue (saline or atropine). During the test, the ECG values for both heart rhythm and heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) are monitored. While many laboratories measure only arm-cuff BP every 2 to 5 minutes, continuous BP measurements (either with an arterial line or with continuous noninvasive technology) provide more information, especially at the time of hypotension and fainting when an automatic arm cuff can sometimes pose difficulties in documenting BP. Adjunctive investigations can be combined with the HUTT in special circumstances, and some are listed in Table 71-2.

| MATERIALS AND EQUIPMENT NEEDED |

HUTT, Head-uptilt-table test; ECG, electrocardiogram; BP, blood pressure; IV, intravenous; RN, registered nurse; TKVO, to keep vein open; ACLS, Advanced Cardiac Life Support; NPO, nothing by mouth; NS, normal saline; HR, heart rate.

Table 71-2 Adjunctive Investigations During Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Definition of a Positive Head-up Tilt-Table Test

A positive test for NMS requires both the presence of hypotension (usually with relative or absolute bradycardia) and the reproduction of some clinical symptoms before and after the faint. Investigators of the VASIS (Vasovagal Syncope International Study) developed a classification scheme to subcategorize positive hemodynamic responses to the HUTT on the basis of the relative roles of bradycardia and vasodepression (Table 71-3), although the clinical usefulness of the classification is not yet clear. Some patients can have a typical hemodynamic pattern for NMS, but the symptoms are not clinically reminiscent. While these patients may be predisposed to this type of fainting, it may be unrelated to their current clinical problems. The HUTT can also demonstrate patterns of orthostatic tachycardia or orthostatic hypotension (immediate or delayed).

Table 71-3 Revised Vasovagal Syncope International Study (VASIS) Classification of Positive Head-up Tilt-Table Test45

| TYPE 1: MIXED |

| Heart rate falls at the time of syncope, but the ventricular rate does not fall to <40 beats/min or falls to <40 beats/min for less than 10 seconds with or without asystole of <3 seconds. Blood pressure falls before heart rate falls. |

| TYPE 2A: CARDIOINHIBITION WITHOUT ASYSTOLE |

| Heart rate falls to a ventricular rate <40 beats/min for more than 10 seconds, but asystole of more than 3 seconds does not occur. Blood pressure falls before heart rate falls. |

| TYPE 2B: CARDIOINHIBITION WITH ASYSTOLE |

| Asystole occurs for more than 3 seconds. Heart rate fall coincides with or precedes blood pressure fall. |

| TYPE 3: VASODEPRESSOR |

| Heart rate does not fall more than 10% from its peak at the time of syncope. |

Passive Drug-Free Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Protocol

The traditional HUTT protocol involves tilting a subject to at least 60 degrees head-up tilt or more commonly to 70 to 80 degrees head-up tilt for up to 45 minutes’, duration.14–16 Drug-free protocols have reported positive yields of about 50% and specificities of about 90%.1 The primary advantage of these protocols is that only passive orthostatic stress is involved, without the possible confounding effects of a nonphysiological response to a drug.

Isoproterenol and the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Protocol

After a short drug-free HUTT phase, patients are infused with incremental doses of isoproterenol ranging from 1 to 3 µg/min for 10 minutes at each level of isoproterenol. Doses of 5 µg/min at an angle of more than 80 degres for more than 10 minutes provoke a high rate of false-positive tests. However, using only a 15-minute drug-free HUTT followed by isoproterenol 1 to 3 µg/min has a reported positive test rate of ~60% and specificity greater than 90%.9

Nitroglycerin and the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Protocol

Intravenous nitroglycerin infusions and sublingual nitroglycerin with tilt testing also provoke the neurally mediated response.10,11 Sublingual nitroglycerin 0.3 to 0.4 mg following a 45-minute drug-free HUTT has a positive test rate for patients with syncope of unknown origin of 61% and a specificity of 94%.2 The advantages of sublingual nitroglycerin over isoproterenol are improved convenience, improved tolerance, and ease of use. Although both isoproterenol HUTT and nitroglycerin HUTT have comparable rates of positive tests and true-negative rates, Oraii et al17 found that 75% of their cases had discordant responses to the two tests, suggesting that the provocative agents may provide complementary information.

Clomipramine and the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Protocol

Theodorakis et al12 reported that a protocol that included infusing intravenous clomipramine 5 mg over 5 minutes was associated with a total positive response rate (both passive phase and with clomipramine) of 80% and a specificity of more than 95%. The putative mechanism involves an acute increase in synaptic serotonin because of acute serotonin reuptake blockade. This has not been widely used, possibly because of difficulty in obtaining the drug outside Europe.

Physiology Underlying the Head-up Tilt Table Test

Assumption of the upright posture requires prompt physiological adaptation to gravity.18 About 500 mL of blood rapidly descends from the thorax to the lower abdomen, buttocks, and legs. In addition, a 10% to 25% shift of plasma volume out of the vasculature and into the interstitial tissue occurs, mostly within 10 minutes of upright posture, with a slow ongoing shift after that time.19,20 This shift decreases venous return to the heart, resulting in a transient decline in both arterial pressure and cardiac filling. This has the effect of reducing the pressure on the baroreceptors, triggering a compensatory sympathetic activation that results in an increase in HR and systemic vasoconstriction (countering the initial decline in BP). Hence, assumption of upright posture results in a 10 to 20 beats/min increase in HR, a negligible change in systolic BP, and an approximately 5 mm Hg increase in diastolic BP.

The most common pathophysiological explanation for NMS is known as the ventricular hypothesis.21 This hypothesis argues that the initiating event is a pooling of blood in the legs (from prolonged sitting or standing) with a resultant reduction in venous return (preload) to the heart. The resultant decrease in BP leads to a baroreceptor-mediated increase in sympathetic tone. This increased sympathetic tone leads to increased chronotropic and inotropic effects. The vigorous contraction, in the setting of an underfilled ventricle, is thought to stimulate unmyelinated nerve fibers (ventricular afferents) in the left ventricle. This is then thought to trigger a reflex loss of sympathetic tone and an associated vagotonia (with resultant hypotension, bradycardia, or both).

This hypothesis seems to provide a plausible explanation for the postural prodrome to many of the episodes of NMS and provides a rationale for the use of the HUTT. However, even among patients with postural NMS, some experimental observations do not fit completely within this model.21

Accuracy of the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Gold Standard Populations

Tilt testing has a core problem: It has not been validated against a syndrome that has gold standard diagnostic criteria. In essence, the syndrome is defined by tilt tests rather than being diagnosed by tilt tests. Waxman et al reported that isoproterenol tilt tests induce syncope or presyncope in 75% of subjects with pre-existing classic NMS induced by situations such as the sight of blood or medical procedures.22 However, Agarwal et al reported that of their 12 subjects who developed the neurally mediated reflex during angioplasty sheath withdrawal, none had positive tilt tests.23 Therefore, most reports on tilt tests refer to the proportion of positive studies as positive yield rather than as sensitivity.

Head-up Tilt-Table Test Sensitivity

A positive response was seen in 49% of drug-free HUTTs and 61% to 69% of drug-provoked tests in patients with prior syncope.1,2 It is possible that many patients with NMS may have false-negative tilt tests. Even aggressive tilt protocols using isoproterenol appear to be incompletely sensitive in the case of patients who otherwise are similar to those with positive tilt tests.24

Specificity of the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Studies of the specificity of tilt tests are equally difficult to interpret. The first lifetime syncopal spell can occur at any age up to about 45 years, and the lifetime prevalence is around 40%.5 This raises several problems. First, how many healthy control subjects are predisposed to faint but have simply not yet fainted? Second, if the HUTT identifies people predisposed to fainting, then populations of younger control subjects will appear to have more false-positive tilt tests. This will confound the studies on aging and the autonomic nervous system. Finally, the specificity of a tilt test protocol seems to be inversely related to its positive yield. Thus a “false-positive” tilt may be a mistake (it may be truly false), or it may reflect a physiological propensity to a neurally mediated reaction that has yet to manifest clinically. No ideal protocol exists, but an optimal compromise appears to have both test positivity and specificity around 70% to 75%.

Effect of Protocol Variability on the Head-up Tilt-Table Test Results

Controlled studies have shown that the likelihood of positive tests depends on whether intravenous cannulation is used, the angle and duration of the HUTT, whether and how a drug challenge is used, the number of head-up iterations during the test, the volume status of the subject, and the subject’s age.2,16,25–33 Outcomes can be quite sensitive to subtle changes in tilt conditions. Protocols that use a longer observation period, a steeper tilt angle, and drug interventions have a higher diagnostic yield and lower specificity. Similarly, younger subjects are more sensitive to tilt testing, whether or not isoproterenol is used. While both isoproterenol and nitroglycerin increase the diagnostic yield of the HUTT by the same proportion, the two provocative agents might select different patients.17

Reproducibility of the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Tilt tests are 70% to 87% reproducible over intervals of days to months when both presyncope and syncope are deemed to be positive test outcomes.2 This may reflect the alterations in testing conditions or reflect a “training effect” with physiological adaptation to the HUTT. On the basis of this observation, Ector et al have developed orthostatic tilt training as a treatment for NMS.34 Given this apparent “training effect,” the HUTT should not be used in a serial fashion to assess response to drug therapy for NMS.

Prognostic Utility of the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Tilt Tests and Clinical Outcomes

HUTTs do not predict the future clinical course of patients. In three studies, patients had similar rates of syncope recurrence after the HUTT whether the test outcome was negative or positive.24,35,36 As well, the ISSUE (International Study on Syncope of Uncertain Etiology) investigators reported that the degree of bradycardia elicited during a positive tilt test failed to correlate with the degree of bradycardia recorded on an implanted loop recorder during a subsequent syncopal spell in the community.36 Thus, the HUTT fails to predict the future clinical outcomes of patients.

Ability to Select Efficacious Clinical Therapy

Although some have proposed using tilt-table testing as a way to select efficacious therapy, this strategy has not been shown to work. The fact that β-blockers can prevent syncope during isoproterenol tilt tests suggests that the need for isoproterenol to obtain a positive tilt test would predict eventual clinical benefits from β-blockers. This was tested as a formal substudy of the Prevention of Syncope Trial and was conclusively disproven.37 A related hypothesis was that profound bradycardia or asystole on a tilt test would predict eventual clinical benefit from permanent cardiac pacing. This, too, seems unlikely. Two observational, historically controlled studies of pacing and syncope and the Second Vasovagal Pacemaker Study concluded that the degree of bradycardia on baseline tilt tests did not predict the subsequent likelihood of syncope in patients treated with a permanent pacemaker.38–40 A later meta-analysis that included a patient-specific analysis came to the same conclusion.41

Therefore, results of the HUTT are not useful for prognosis. These results do not predict eventual clinical outcome or improvement with either β-blockers (which probably do not work in most patients) or with pacemakers.37

Guidelines to Order a Head-up Tilt Table Test

Prior to proceeding to the HUTT, a detailed history of the fainting spells should be taken and a focused physical examination performed. The most recent guidelines for the HUTT come from the European Society of Cardiology (2009).2 Tilt testing was felt to be appropriate (or at least worthy of consideration) in the following clinical circumstances (the class of recommendation is listed after each item):

Authors’ Approach to Ordering a Head-up Tilt Table Test

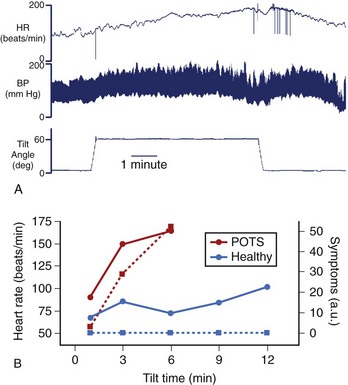

Although the HUTT was clinically developed largely to diagnose NMS, it can also be useful for diagnosing other disorders. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a chronic multisystem disorder that is associated with an excessive (supraphysiological) increase in HR on assuming an upright posture.18 An HUTT will capture this hemodynamic information, as shown in Case Scenario #5. Orthostatic hypotension has traditionally been defined as a drop in BP greater than 20/10 mm Hg within 3 minutes of standing.42 In the recently described phenomenon of delayed orthostatic hypotension, the drop in BP occurs only after longer upright posture, such as with the HUTT.43,44

Case Scenarios: Interpretation of the Head-up Tilt-Table Test

Tilt Scenario 1: Neurally Mediated Syncope

Tilt Results and Interpretation

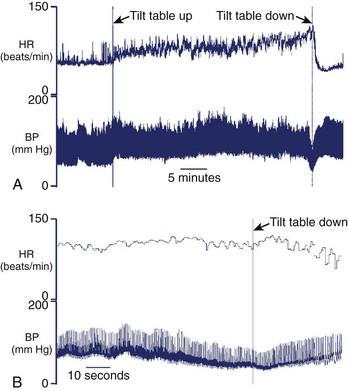

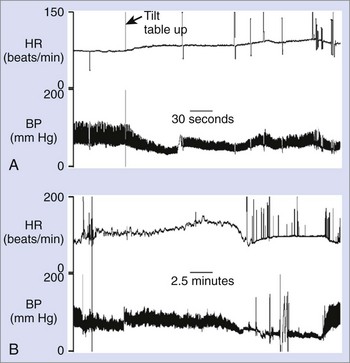

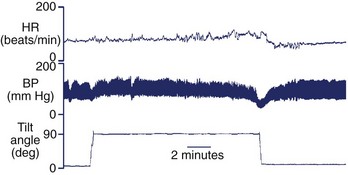

V.V. underwent a drug-free HUTT at a 75-degree head-up tilt for a planned duration of 45 minutes. Immediately on upright tilt, a small increase in both HR and BP occurred (Figure 71-1, A). During the next 30 minutes of ongoing tilt, BP remained stable, although HR slowly increased during prolonged tilt. After 35 minutes, an abrupt decrease occurred in BP over ~20 seconds, immediately preceded by some BP cycling (see Figure 71-1, B). The nadir systolic BP was 78 mm Hg and was associated with severe presyncope that reproduced his clinical symptoms. BP began to recover as soon as the tilt table was returned to the supine position.

This hemodynamic pattern is typical of NMS. The patient had stable HR and BP for over 30 minutes during the head-up tilt. Then a rather precipitous decrease in BP associated with severe presyncope occurred. This is a vasodepressor pattern (VASIS type 3; see Table 71-3).45 In the authors’ laboratory, this is the most commonly seen hemodynamic pattern with a positive HUTT.

Tilt Scenario 2: Neurally Mediated Syncope with Nitroglycerin Provocation

Tilt Results and Interpretation

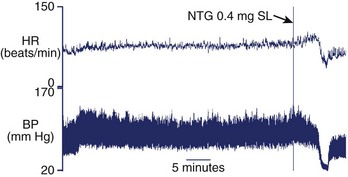

Immediately on a head-up tilt to 75 degrees, P.A.’s HR and BP increased slightly. This hemodynamic pattern remained stable for the remaining 30 minutes of drug-free tilt (Figure 71-2). He was then given sublingual nitroglycerin 0.4 mg as a provocative agent. As a result of nitroglycerin-induced venodilation, P.A.’s BP decreased slightly and his HR increased slightly. This was not a positive result but a direct hemodynamic response to the nitroglycerin. After a few minutes, both his HR and his BP fell rapidly, and he had an episode of syncope. He felt warm and diaphoretic, which mimicked his clinical spells.

Several drugs have been used to increase the yield or sensitivity of the HUTT. These include isoproterenol, nitroglycerin, and clomipramine. All of these agents increase the sensitivity of the HUTT at the expense of a decrease in specificity (see Protocols and Procedures for the Head-Up Tilt Test for details). Here, the diagnosis was established when his clinical symptoms were reproduced when he had both hypotension and bradycardia.

Tilt Scenario 3: False-Positive Tilt Test Result

Tilt Results and Interpretation

She underwent a drug-free HUTT at a 60-degree head-up tilt. After 13 minutes, she began to feel lightheaded. Her BP decreased suddenly (Figure 71-3), and she experienced frank syncope after just 14 minutes into the HUTT. The table was returned to the horizontal position, and she rapidly recovered.

FIGURE 71-3 False-positive tilt test. Heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) in response to head-up tilt-table test are similar to that seen in Figure 71-1. Since this patient had never fainted clinically outside this test, this is a false-positive response to tilt-table testing.

Her hemodynamic pattern during the HUTT is very similar to that of the NMS patient (see Figure 71-1, A). Both demonstrated a tilt pattern consistent with NMS—a prolonged maintenance of BP followed by rapid hypotension culminating in frank syncope or severe presyncope. She does not have NMS as such, since NMS is a clinical diagnosis and she has not had clinical syncope. This is a false-positive result, although in time she might have clinical syncope.

Tilt Scenario 4: Convulsive Syncope

Tilt Results and Interpretation

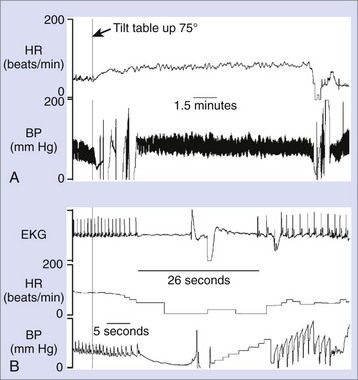

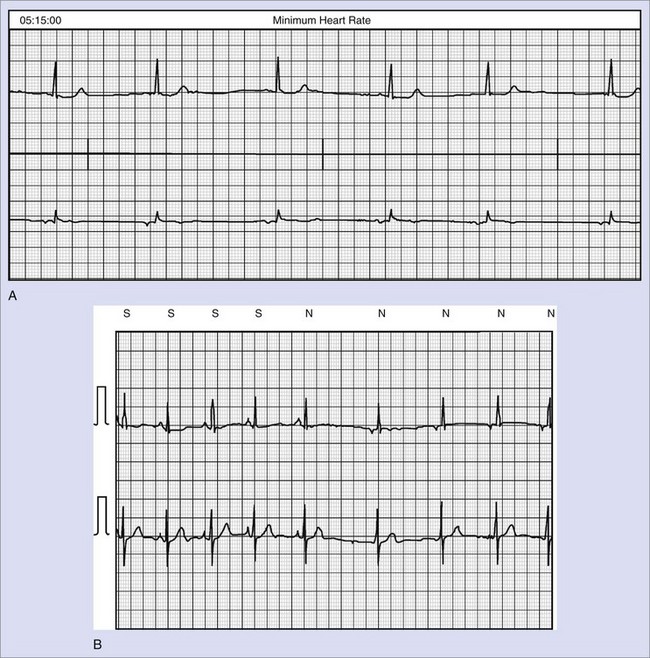

C.S. underwent a drug-free HUTT at a 75-degree head-up tilt, with continuous monitoring of HR and BP. About 14 minutes into tilt, the patient described stomach discomfort and nausea. Shortly after that, his HR slowed, and he developed 26 seconds of asystole (Figure 71-4, A). This loss of consciousness was accompanied by myoclonic jerks that resembled a “seizure” (note the artifacts in the BP signal following asystole in Figure 71-4, B).

Tilt Scenario 5: Postural Tachycardia Syndrome

Tilt Results and Interpretation

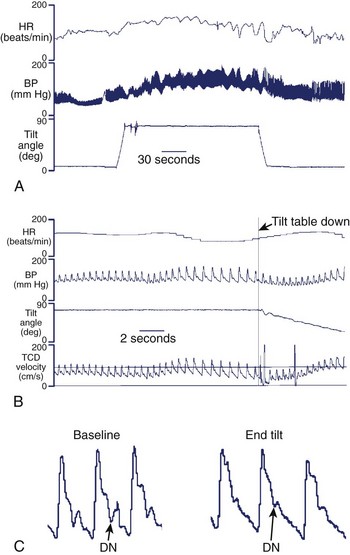

O.T. underwent a drug-free HUTT at a 60-degree head-up tilt. Immediately after the tilt, her BP increased (Figure 71-5, A). A striking increase in her HR from 80 beats/min at baseline to 164 beats/min at 3 minutes following the onset of the tilt was seen. In contrast to the patient with neurally mediated hypotension, O.T. began experiencing significant orthostatic symptoms almost immediately after assuming an upright posture, and these became worse with ongoing upright tilt (see Figure 71-5, B). These symptoms and elevated HR improved quickly once the table was returned to the horizontal position. The cardinal criterion for POTS is an excessive increase in HR on assuming an upright posture (>30 beats/min increase within 10 minutes) in the absence of orthostatic hypotension (a drop >20/10 mm Hg). The diagnostic criteria for POTS require the aforementioned hemodynamic criteria plus a constellation of typical symptoms that get worse with the upright posture and improve with the recumbent posture.18,46 Only a minority of patients with POTS report frank syncope.47

Tilt Scenario 6a: Neurogenic Orthostatic Hypotension

Tilt Results and Interpretation

Within seconds after the table was raised to a 75-degree head-up tilt, M.P.’s BP fell, with only a minimal increase in HR (Figure 71-6, A). His BP was 112/74 mm Hg at baseline, and this fell to 69/51 mm Hg within 3 minutes of the HUTT (meeting the criteria for significant orthostatic hypotension). He maintained this BP for the remainder of the test. This hypotension reproduced his clinical presyncope.

This patient has neurogenic orthostatic hypotension with a decrease in BP more than 20/10 mm Hg within 3 minutes of upright posture and only a modest reflex increase in HR.42 Hemodynamic patterns can be variable. Some patients can maintain their lower BP with ongoing orthostatic stress, while in others BP progressively decreases.48 Neurogenic orthostatic hypotension can be caused by a peripheral autonomic neuropathy (Bradbury-Eggleston syndrome; pure autonomic failure) or a central autonomic disorder (Shy-Drager Syndrome49; multiple systems atrophy). Treatment usually involves a combination of blood volume expansion and vasopressor agents.50

Tilt Scenario 6b: Delayed Orthostatic Hypotension

Tilt Result and Interpretation

Within a few minutes of a 75-degree head-up tilt, her systolic BP fell by 14 mm Hg at 3 minutes (see Figure 71-6, B). This does not meet the criterion for orthostatic hypotension.42 With ongoing tilt, her BP continued to drift downward. Her systolic BP reached a nadir of 52 mm Hg at 24 minutes of head-up tilt. Shortly thereafter, the patient felt nauseated and severely lightheaded, which mimicked her clinical spells.

Delayed orthostatic hypotension is characterized by a slow and gradual decrease in BP that does not occur immediately, as is typically seen with neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. In contrast to the initially stable BP followed by a sudden drop (falling off a cliff), as is seen with NMS (see Figure 71-1), BP gradually declines in delayed orthostatic hypotension (akin to rolling down a ramp). The exact underlying causes are not known, but the hypotension may be caused by mild failure of the autonomic nervous system in some cases.

Tilt Scenario 7: Syncope with a “Normal” BP—Cerebral Syncope

Tilt Result and Interpretation

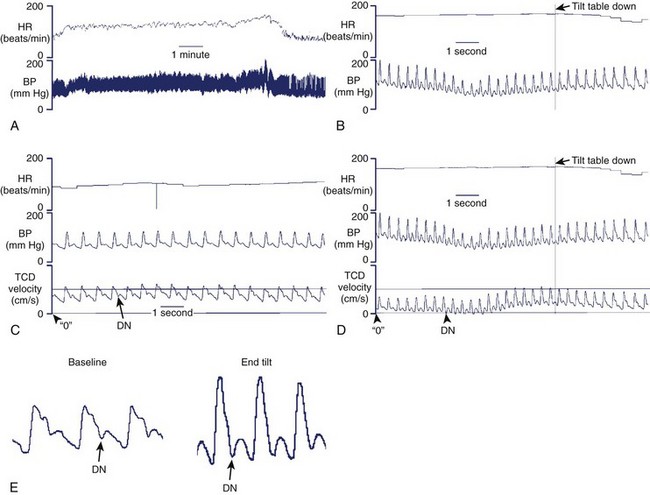

C.T. underwent a drug-free 75-degree HUTT for a planned duration of 45 minutes. On upright tilt, a small increase in both HR and BP occurred (Figure 71-7, A). After 9 minutes of HUTT, C.T. lost consciousness. Her HR was 150 beats/min, and her systolic BP was never below 100 mm Hg (see Figure 71-7, B). The table was returned to the horizontal position, and she rapidly regained consciousness.

Given her prior history of tilt-table–induced syncope without hypotension, this HUTT was performed with TCD ultrasound of her right middle cerebral artery. Figure 71-7, C, shows the TCD velocity signal in addition to the HR and BP at the start of the study. The TCD signal has a prominent dicrotic notch in mid-diastole and shows evidence of good diastolic cerebral flow (TCD velocity well above 0 cm/s). Figure 71-7, D, shows the end of the tilt. At the time of LOC (just before the table was returned to the horizontal position), the first TCD velocity wave (including systole and the early phase of diastole) narrowed, the dicrotic notch deepened, and the diastolic cerebral flow was negligible (flow velocity approaches 0 cm/s). Almost immediately after the table was returned to the horizontal position, the TCD velocity waveform started to revert to the baseline, with the dicrotic notch and diastolic flows at a higher velocity. The difference between the “baseline” and “end” TCD velocity waveforms can be seen best in Figure 71-7, E.

These isolated changes in cerebral blood flow velocity are thought to represent isolated cerebral vasospasms. Syncope caused by this isolated change in cerebral blood flow has been termed cerebral syncope.50 No clinical trial data are available to guide clinicians on the optimal management of patients with cerebral syncope. If an adequate prodrome is present, hyperventilation can be attempted (using a paper bag), as this can cause cerebral vasodilation. Otherwise, traditional pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches to NMS can be attempted.

Tilt Scenario 8: Syncope with a “Normal” BP: Psychogenic Syncope

Tilt Result and Interpretation

P.S. underwent a drug-free 75-degree HUTT. On upright tilt, HR and BP increased (Figure 71-8, A). After 5 minutes of HUTT, she lost consciousness while her systolic BP was greater than 120 mm Hg. The table was returned to the horizontal position.

Review of the TCD ultrasound signal during apparent LOC at the end of the tilt (see Figure 71-8, B) revealed a waveform with a prominent dicrotic notch and diastolic flow velocities (well above 0 cm/s), indicating cerebral diastolic perfusion. A comparison of the TCD waveform from baseline with the end of the tilt does not reveal significant changes in morphology (see Figure 71-8, C).

Tilt Scenario 9: Hypersensitive Carotid Sinus Syndrome

Tilt Result and Interpretation

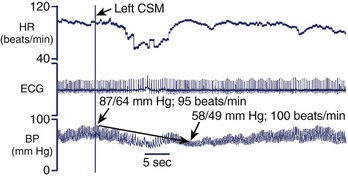

F.T. underwent an HUTT with continuous HR and noninvasive BP monitoring. Immediately after tilting to a 75-degree head-up tilt, her HR was 95 beats/min and her BP was 87/64 mm Hg (Figure 71-9). Digital pressure was then applied over the left carotid bulb. Within several seconds, she lost consciousness. An initial decrease in F.T.’s HR was seen, but it then returned to baseline. Her BP, however, decreased to 58/49 mm Hg. Her BP and consciousness recovered shortly after the table was returned to the horizontal position.

Key References

Connolly SJ, Sheldon R, Thorpe KE, et al. Pacemaker therapy for prevention of syncope in patients with recurrent severe vasovagal syncope: Second Vasovagal Pacemaker Study (VPS II): A randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2224-2229.

1996 Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, pure autonomic failure, and multiple system atrophy. The Consensus Committee of the American Autonomic Society and the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 1996;46:1470.

Delepine S, Prunier F, Leftheriotis G, et al. Comparison between isoproterenol and nitroglycerin sensitized head-upright tilt in patients with unexplained syncope and negative or positive passive head-up tilt response. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:488-491.

Ector H, Reybrouck T, Heidbuchel H, et al. Tilt training: A new treatment for recurrent neurocardiogenic syncope and severe orthostatic intolerance. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:193-196.

el Bedawi KM, Hainsworth R. Combined head-up tilt and lower body suction: A test of orthostatic tolerance. Clin Auton Res. 1994;4:41-47.

El Sayed H, Hainsworth R. Salt supplement increases plasma volume and orthostatic tolerance in patients with unexplained syncope. Heart. 1996;75:134-140.

Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Delayed orthostatic hypotension: A frequent cause of orthostatic intolerance. Neurology. 2006;67:28-32.

Grubb BP. Cerebral syncope: New insights into an emerging entity. J Pediatr. 2000;136:431-432.

Julu PO, Cooper VL, Hansen S, Hainsworth R. Cardiovascular regulation in the period preceding vasovagal syncope in conscious humans. J Physiol. 2003;549:299-311.

Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(21):2631-2671.

Mosqueda-Garcia R, Furlan R, Tank J, Fernandez-Violante R. The elusive pathophysiology of neurally mediated syncope. Circulation. 2000;102:2898-2906.

Raj SR. The postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS): Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2006;6:84-99.

Schondorf R, Low PA. Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: An attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia? Neurology. 1993;43:132-137.

Sheldon R, Connolly S, Rose S, et al. Prevention of Syncope Trial (POST): A randomized, placebo-controlled study of metoprolol in the prevention of vasovagal syncope. Circulation. 2006;113:1164-1170.

Sud S, Massel D, Klein GJ, et al. The expectation effect and cardiac pacing for refractory vasovagal syncope. Am J Med. 2007;120:54-62.

1 Kapoor WN, Smith MA, Miller NL. Upright tilt testing in evaluating syncope: A comprehensive literature review. Am J Med. 1994;97:78-88.

2 Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(21):2631-2671.

3 Sheldon R, Connolly S, Rose S, et al. Prevention of Syncope Trial (POST): A randomized, placebo-controlled study of metoprolol in the prevention of vasovagal syncope. Circulation. 2006;113:1164-1170.

4 Julu PO, Cooper VL, Hansen S, Hainsworth R. Cardiovascular regulation in the period preceding vasovagal syncope in conscious humans. J Physiol. 2003;549:299-311.

5 Ganzeboom KS, Colman N, Reitsma JB, et al. Prevalence and triggers of syncope in medical students. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:1006-1008. A8

6 Brignole M, Menozzi C, Bartoletti A, et al. A new management of syncope: Prospective systematic guideline-based evaluation of patients referred urgently to general hospitals. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:76-82.

7 Abi-Samra F, Maloney JD, Fouad-Tarazi FM, Castle LW. The usefulness of head-up tilt testing and hemodynamic investigations in the workup of syncope of unknown origin. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1988;11:1202-1214.

8 Kenny RA, Ingram A, Bayliss J, Sutton R. Head-up tilt: A useful test for investigating unexplained syncope. Lancet. 1986;1:1352-1355.

9 Morillo CA, Klein GJ, Zandri S, Yee R. Diagnostic accuracy of a low-dose isoproterenol head-up tilt protocol. Am Heart J. 1995;129:901-906.

10 Raviele A, Gasparini G, Di Pede F, et al. Nitroglycerin infusion during upright tilt: A new test for the diagnosis of vasovagal syncope. Am Heart J. 1994;127:103-111.

11 Raviele A, Menozzi C, Brignole M, et al. Value of head-up tilt testing potentiated with sublingual nitroglycerin to assess the origin of unexplained syncope. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:267-272.

12 Theodorakis GN, Markianos M, Zarvalis E, et al. Provocation of neurocardiogenic syncope by clomipramine administration during the head-up tilt test in vasovagal syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:174-178.

13 el Bedawi KM, Hainsworth R. Combined head-up tilt and lower body suction: A test of orthostatic tolerance. Clin Auton Res. 1994;4:41-47.

14 Fitzpatrick AP, Theodorakis G, Vardas P, Sutton R. Methodology of head-up tilt testing in patients with unexplained syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:125-130.

15 Almquist A, Goldenberg IF, Milstein S, et al. Provocation of bradycardia and hypotension by isoproterenol and upright posture in patients with unexplained syncope. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:346-351.

16 Natale A, Akhtar M, Jazayeri M, et al. Provocation of hypotension during head-up tilt testing in subjects with no history of syncope or presyncope. Circulation. 1995;92:54-58.

17 Oraii S, Maleki M, Minooii M, Kafaii P. Comparing two different protocols for tilt table testing: Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate versus isoprenaline infusion. Heart. 1999;81:603-605.

18 Raj SR. The Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): Pathophysiology, diagnosis & management. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2006;6:84-99.

19 Raj SR, Biaggioni I, Yamhure PC, et al. Renin-aldosterone paradox and perturbed blood volume regulation underlying postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:1574-1582.

20 Jacob G, Ertl AC, Shannon JR, et al. Effect of standing on neurohumoral responses and plasma volume in healthy subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:914-921.

21 Mosqueda-Garcia R, Furlan R, Tank J, Fernandez-Violante R. The elusive pathophysiology of neurally mediated syncope. Circulation. 2000;102:2898-2906.

22 Waxman MB, Yao L, Cameron DA, et al. Isoproterenol induction of vasodepressor-type reaction in vasodepressor-prone persons. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:58-65.

23 Agarwal R, Yadave RD, Bhargava B, et al. Head-up tilt test (HUTT) in patients with episodic bradycardia and hypotension following percutaneous coronary interventions. J Invasive Cardiol. 1997;9:601-603.

24 Sheldon R, Rose S, Koshman ML. Comparison of patients with syncope of unknown cause having negative or positive tilt-table tests. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:581-585.

25 McIntosh SJ, Lawson J, Kenny RA. Intravenous cannulation alters the specificity of head-up tilt testing for vasovagal syncope in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 1994;23:317-319.

26 Sheldon R, Koshman ML. A randomized study of tilt test angle in patients with undiagnosed syncope. Can J Cardiol. 2001;17:1051-1057.

27 Sheldon R, Killam S. Methodology of isoproterenol-tilt table testing in patients with syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:773-779.

28 El Sayed H, Hainsworth R. Salt supplement increases plasma volume and orthostatic tolerance in patients with unexplained syncope. Heart. 1996;75:134-140.

29 Mangru NN, Young ML, Mas MS, et al. Usefulness of tilt table test with normal saline infusion in management of neurocardiac syncope in children. Am Heart J. 1996;131:953-955.

30 Burklow TR, Moak JP, Bailey JJ, Makhlouf FT. Neurally mediated cardiac syncope: Autonomic modulation after normal saline infusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:2059-2066.

31 Sheldon R. Effects of aging on responses to isoproterenol tilt-table testing in patients with syncope. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:459-463.

32 Bloomfield D, Maurer M, Bigger JTJr. Effects of age on outcome of tilt-table testing. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1055-1058.

33 Delepine S, Prunier F, Leftheriotis G, et al. Comparison between isoproterenol and nitroglycerin sensitized head-upright tilt in patients with unexplained syncope and negative or positive passive head-up tilt response. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:488-491.

34 Ector H, Reybrouck T, Heidbuchel H, et al. Tilt training: A new treatment for recurrent neurocardiogenic syncope and severe orthostatic intolerance. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:193-196.

35 Grimm W, Degenhardt M, Hoffman J, et al. Syncope recurrence can better be predicted by history than by head-up tilt testing in untreated patients with suspected neurally mediated syncope. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:1465-1469.

36 Moya A, Brignole M, Menozzi C, et al. Mechanism of syncope in patients with isolated syncope and in patients with tilt-positive syncope. Circulation. 2001;104:1261-1267.

37 Raj SR, Koshman ML, Sheldon RS. Outcome of patients with dual-chamber pacemakers implanted for the prevention of neurally mediated syncope. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:565-569.

38 Petersen ME, Chamberlain-Webber R, Fitzpatrick AP, et al. Permanent pacing for cardioinhibitory malignant vasovagal syndrome. Br Heart J. 1994;71:274-281.

39 Connolly SJ, Sheldon R, Thorpe KE, et al. Pacemaker therapy for prevention of syncope in patients with recurrent severe vasovagal syncope: Second Vasovagal Pacemaker Study (VPS II): A randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2224-2229.

40 Sud S, Massel D, Klein GJ, et al. The expectation effect and cardiac pacing for refractory vasovagal syncope. Am J Med. 2007;120:54-62.

41 Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, pure autonomic failure, and multiple system atrophy. The Consensus Committee of the American Autonomic Society and the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 1996;46:1470.

42 Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Delayed orthostatic hypotension: A frequent cause of orthostatic intolerance. Neurology. 2006;67:28-32.

43 Podoleanu C, Maggi R, Oddone D, et al. The hemodynamic pattern of the syndrome of delayed orthostatic hypotension. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2009;26(2):143-149.

44 Brignole M, Menozzi C, Del Rosso A, et al. New classification of haemodynamics of vasovagal syncope: Beyond the VASIS classification. Analysis of the pre-syncopal phase of the tilt test without and with nitroglycerin challenge. Vasovagal Syncope International Study. Europace. 2000;2:66-76.

45 Schondorf R, Low PA. Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: An attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia? Neurology. 1993;43:132-137.

46 Stewart JM. Chronic orthostatic intolerance and the postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). J Pediatr. 2004;145:725-730.

47 Gehrking JA, Hines SM, Benrud-Larson LM, et al. What is the minimum duration of head-up tilt necessary to detect orthostatic hypotension? Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:71-75.

48 Shy GM, Drager GA. A neurological syndrome associated with orthostatic hypotension: A clinical-pathologic study. Arch Neurol. 1960;2:511-527.

49 Freeman R. Clinical practice. Neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:615-624.

50 Grubb BP. Cerebral syncope: New insights into an emerging entity. J Pediatr. 2000;136:431-432.