Head injury

Head injury is an important cause of disability and death. In western countries, trauma is the most common cause of death in patients aged under 45 years. Half of these patients die as a result of head injury. Overall there is a mortality rate of 20–30 per 100 000 per year. The survivors are often disabled with a prevalence of disabled survivors of up to 400 per 100 000.

Pathology and pathogenesis

Cerebral injury

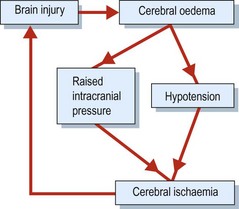

There may be secondary brain injury (Fig. 1) due to brain oedema, which causes raised intracranial pressure and can lead to cerebral herniation (p. 48). The raised intracranial pressure, usually associated with hypotension, leads to hypoperfusion of the brain and therefore cerebral ischaemia. Infratentorial lesions can obstruct CSF flow and lead to hydrocephalus.

Intracranial haematomas

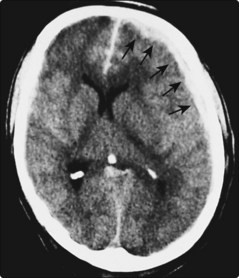

Extradural haematomas occur when the middle meningeal artery bleeds into the extradural space (Fig. 2). This can occur some time after the head injury and should be considered in any patient with deterioration following an apparently good recovery from a head injury.

Subdural haematomas occur either acutely, usually with some intracerebral bleeding, or chronically (Fig. 3). The latter occurs when damaged cortical veins ooze into the subdural space.

Intracerebral haematomas (Fig. 2) are the most common, occurring both at the site of direct trauma and at the contre-coup site.

The mass effect of any of these bleeds may lead to cerebral herniation.

Skull fractures

These can be divided into simple and depressed fractures and basal skull fractures. The latter are difficult to see on skull X-rays but are associated with particular physical signs such as periorbital bruising or Battle’s sign (Fig. 4). These may also be associated with cranial nerve damage, especially facial and auditory nerves. Basal fractures also produce bleeding into the middle ear, seen as either blood behind the ear drum or coming from the external ear, or CSF rhinorrhoea. CSF rhinorrhoea is seen as clear fluid coming from the nose – fluid which, unlike mucus, contains glucose, which is easily tested for. (A more specific test is isotransferrin.) The presence of a skull fracture substantially increases the risk of significant intracranial haemorrhage.

Clinical features

The severity of a head injury can be assessed in several ways:

The level of consciousness, reliably and easily measured using the Glasgow Coma Scale (p. 129), which is an important clinical measure.

The level of consciousness, reliably and easily measured using the Glasgow Coma Scale (p. 129), which is an important clinical measure.One group of patients of particular concern are those who have made an initial recovery from their head injury but then later deteriorate again after a ‘lucid interval’. This is the classical history of patients with extradural haemorrhage, though it can occur with subdural haemorrhage. It can also occur because of neck trauma resulting in carotid dissection. These complications are rare in patients who have not fractured their skull (1 in 1000).

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnosis of head injury will depend on the clinical presentation. In patients who present unconscious or confused, the differential diagnosis is wide and is discussed on page 50. In patients who have had a head injury with a period of anterograde and retrograde amnesia, there may be uncertainty as to whether the head injury was the primary event or the result of a blackout.

Other complications

In addition to the consequences of brain damage there are other complications.