18 Head and Neck Block Anatomy

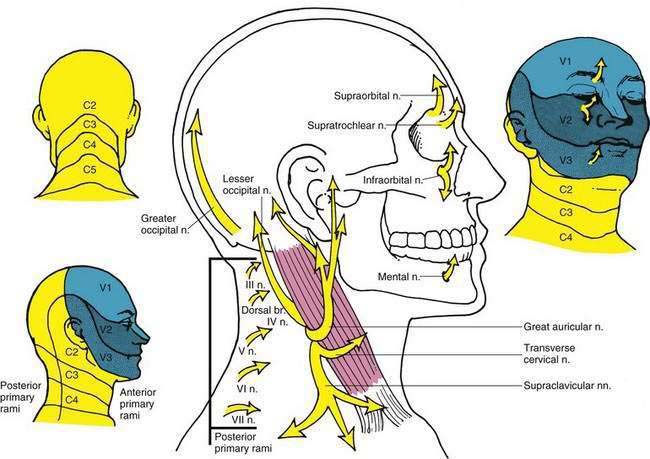

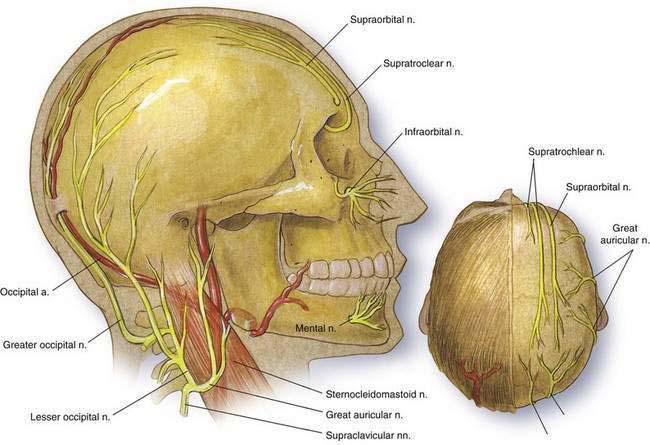

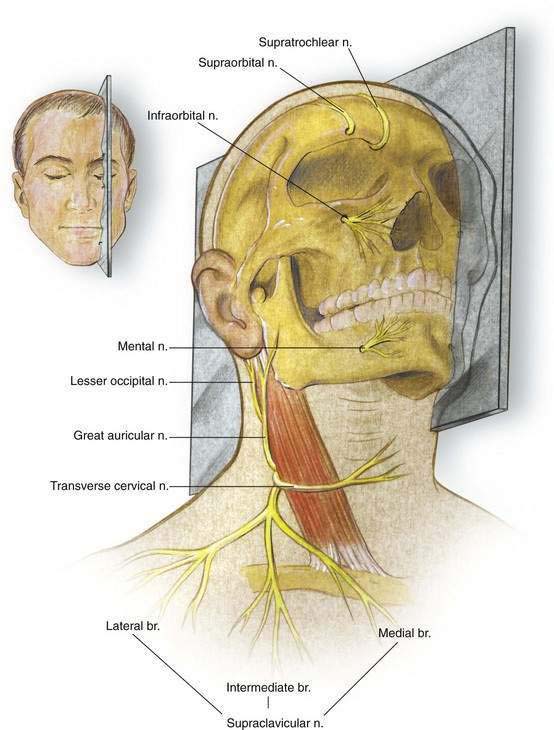

Sensory innervation of the face is provided by the trigeminal nerve. Three branches of the trigeminal—the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular—provide innervation, as illustrated in Figure 18-1. The cutaneous innervation of the posterior head and neck is from the cervical nerves. The dorsal ramus of the second cervical nerve ends in the greater occipital nerve, which provides cutaneous innervation to the larger portion of the posterior scalp (see Fig. 18-1). The greater occipital nerve is a continuation of the medial branch of the dorsal ramus of the second cervical nerve and ascends from the cervical vertebrae to the muscles of the neck in company with the occipital artery. The greater occipital nerve becomes subcutaneous in its course with the occipital artery immediately lateral to the inion, slightly inferior to the superior nuchal line (Fig. 18-2). The ventral rami of cervical nerves II, III, and IV provide the majority of cutaneous innervation to the anterior and lateral portions of the neck, with cervical nerve II providing innervation to the scalp through both the lesser occipital and the posterior auricular nerves (see Fig. 18-1). The superficial cervical plexus is formed as cervical nerves II, III, and IV leave the vertebral transverse processes and follow a course in which they become subcutaneous at the midpoint of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (see Fig. 18-2). At this point, the superficial cervical plexus can be easily blocked by infiltration.

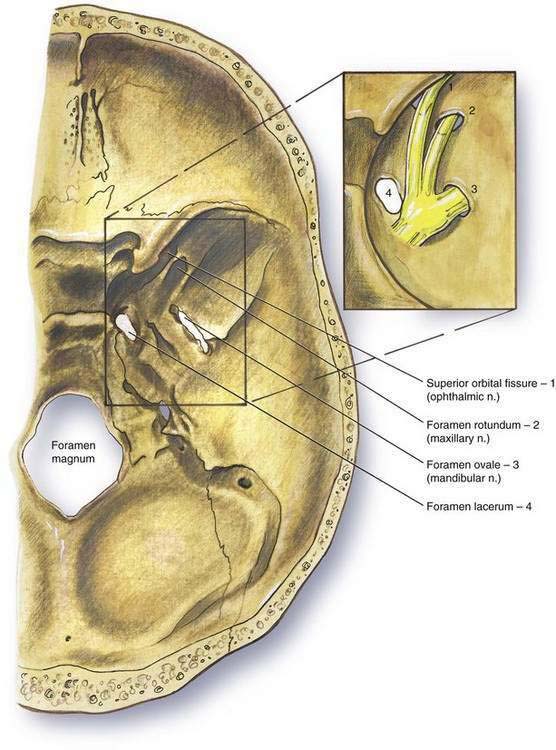

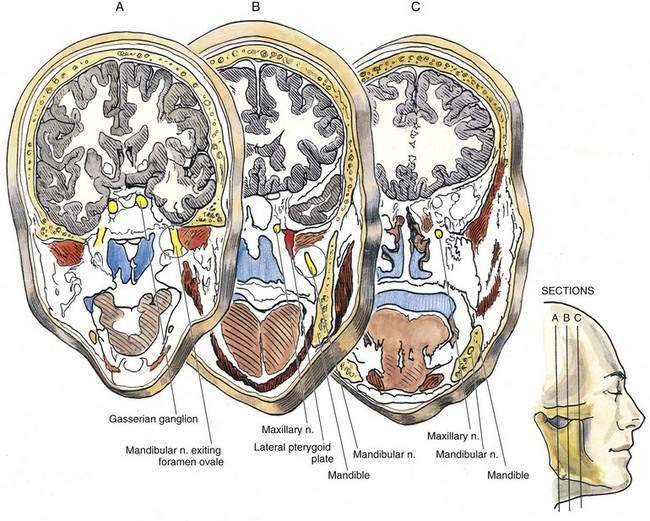

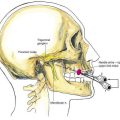

The trigeminal nerve is a mixed motor and sensory nerve, although the majority of it involves sensory innervation. The only motor fibers are the branches that supply the muscles of mastication through the mandibular nerve. The trigeminal nerve is organized in the cranium within the trigeminal ganglion (gasserian or semilunar ganglion). From this ganglion, the ophthalmic nerve exits from the cranium through the superior orbital fissure, the maxillary nerve through the foramen rotundum, and the mandibular nerve through the foramen ovale (Fig. 18-3). After leaving these foramina, the maxillary and mandibular nerves follow courses that place them in the immediate proximity of the lateral pterygoid plate. The pterygoid plate is an important landmark for effective maxillary or mandibular block (Fig. 18-4). The terminal branches of the trigeminal nerve end in the supraorbital, infraorbital, and mental nerves. These exit through bony foramina that occur on a line perpendicular through the pupil, as illustrated in Figure 18-5.