CHAPTER 20 Hand-assisted right colectomy

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

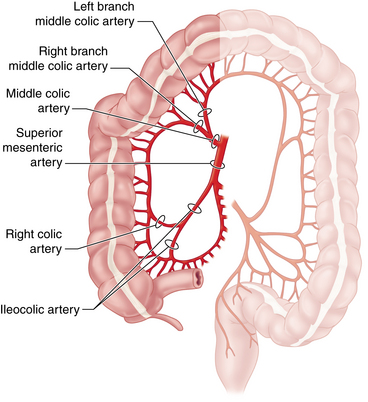

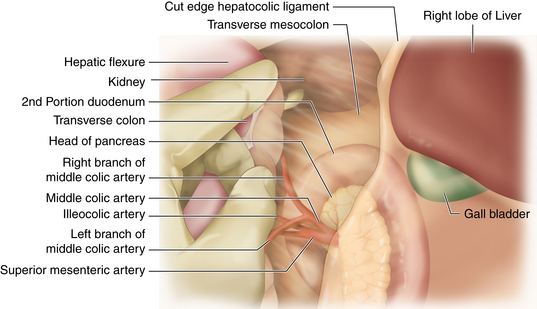

♦ Familiarity with the vascular anatomy of the right colon is essential to the safe conduct of a minimally invasive right colectomy (Figure 20-1). Vascular anatomy also significantly determines resection of colonic malignancies. Several key points guide the laparoscopic surgeon:

The ileocolic artery (ICA) branches from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) just over the duodenum after the take-off of the middle colic artery (MCA). It courses obliquely through the mesocolon to terminate at the cecum, giving off a terminal ileal branch that joins with the small bowel arcade from the SMA.

The ileocolic artery (ICA) branches from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) just over the duodenum after the take-off of the middle colic artery (MCA). It courses obliquely through the mesocolon to terminate at the cecum, giving off a terminal ileal branch that joins with the small bowel arcade from the SMA. The right colic artery is usually a branch of the ICA rather than arising from the SMA as is historically depicted.

The right colic artery is usually a branch of the ICA rather than arising from the SMA as is historically depicted. The MCA proper is typically quite short, branching into two or more arteries (right branch, left branch) just 1 to 2 cm from the aortic origin of the SMA. Rarely is the main MCA itself divided in colon resections. The significant hazard of attempts to control bleeding from a transected main MCA is injury to the SMA.

The MCA proper is typically quite short, branching into two or more arteries (right branch, left branch) just 1 to 2 cm from the aortic origin of the SMA. Rarely is the main MCA itself divided in colon resections. The significant hazard of attempts to control bleeding from a transected main MCA is injury to the SMA. The branches of the MCA are most easily identified from the cranial aspect of the proximal transverse mesocolon. Once these branches and the adjacent mesocolon are transected, the origin of the ICA can be seen retroperitoneally, as can the more medially oriented SMA.

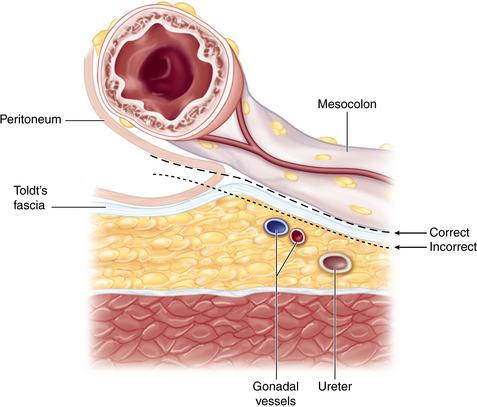

The branches of the MCA are most easily identified from the cranial aspect of the proximal transverse mesocolon. Once these branches and the adjacent mesocolon are transected, the origin of the ICA can be seen retroperitoneally, as can the more medially oriented SMA.♦ The embryologic fusion plane originates laterally at the white line of Toldt, which occurs where the parietal peritoneum fuses with the visceral peritoneal reflection around the colon and its lateral extension (Figure 20-2). The correct dissection plane is the bloodless embryologic fusion plane. When properly mobilized in this plane, the colon reflects medially on its mesentery to become a nearly midline structure. When the dissection is carried posteriorly past the white line of Toldt, violating the parietal peritoneum as it extends across the retroperitoneal structures, the ureter and gonadal vessels are put at risk and mobilization of the colon is limited.

♦ Awareness of the relationships between the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, and proximal transverse colon to neighboring structures helps to maintain orientation during surgery and prevents injury:

The duodenal sweep can be appreciated medial and caudal to the hepatic flexure mesocolon. Risk of injury to the portal triad can be averted by avoiding performance of a Kocher maneuver.

The duodenal sweep can be appreciated medial and caudal to the hepatic flexure mesocolon. Risk of injury to the portal triad can be averted by avoiding performance of a Kocher maneuver. The right kidney and Gerota’s fascia are just lateral to the distal ascending colon. Dissection lateral to the embryologic fusion plane can lead to mobilization of the kidney or the second portion of the duodenum (Kocher maneuver).

The right kidney and Gerota’s fascia are just lateral to the distal ascending colon. Dissection lateral to the embryologic fusion plane can lead to mobilization of the kidney or the second portion of the duodenum (Kocher maneuver). The right ureter descends retroperitoneally and is not typically exposed unless dissection is carried posterior to the embryologic fusion plane.

The right ureter descends retroperitoneally and is not typically exposed unless dissection is carried posterior to the embryologic fusion plane. The lesser sac must be entered in order to take down the hepatic flexure and transect the transverse mesocolon and MCA branches. The stomach, the gastrocolic, and the hepatocolic ligaments constitute its anterior boundary. Posteriorly, one finds the pancreas and, to the right, the duodenal sweep.

The lesser sac must be entered in order to take down the hepatic flexure and transect the transverse mesocolon and MCA branches. The stomach, the gastrocolic, and the hepatocolic ligaments constitute its anterior boundary. Posteriorly, one finds the pancreas and, to the right, the duodenal sweep. The liver and gallbladder are superior to the hepatocolic ligament. Failure to appreciate this plane can lead to dissection of the porta hepatis.

The liver and gallbladder are superior to the hepatocolic ligament. Failure to appreciate this plane can lead to dissection of the porta hepatis.♦ Surface anatomy considerations principally help with optimal port placement:

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

Patient preparation

♦ Given that the majority of right colectomies are performed for neoplastic diseases (cancer or endoscopically unresectable polyps), staging must be complete before going to the operating room:

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is central to the metastatic workup. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan is sometimes also necessary.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is central to the metastatic workup. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan is sometimes also necessary. The CT scan may also reveal invasion into an adjacent structure, which could preclude a laparoscopic approach.

The CT scan may also reveal invasion into an adjacent structure, which could preclude a laparoscopic approach.♦ Lesions must be appropriately localized preoperatively. Although all of the patient’s physicians are concerned about making the correct diagnosis, only the surgeon has to perform a resection and must manage the technical details of this procedure:

Review the colonoscopy report; note the expected location of the target lesion and the presence and character (including pathology report) of any other lesions.

Review the colonoscopy report; note the expected location of the target lesion and the presence and character (including pathology report) of any other lesions. Tattoos are critical for smaller or nonpalpable lesions. Note the type of dye used (India ink lasts, methylene blue disperses).

Tattoos are critical for smaller or nonpalpable lesions. Note the type of dye used (India ink lasts, methylene blue disperses).♦ Plan the extent of resection with regard to both margins and vascular ligation:

The right branch of the MCA should be included for resection of neoplasms of the cecum or the proximal ascending colon.

The right branch of the MCA should be included for resection of neoplasms of the cecum or the proximal ascending colon. For neoplasms of the hepatic flexure or proximal transverse colon, all the MCA branches (or the trunk) must be included.

For neoplasms of the hepatic flexure or proximal transverse colon, all the MCA branches (or the trunk) must be included. For inflammatory bowel disease or other benign indications, there is no need to perform a high ligation of the arteries or regional lymphadenectomy.

For inflammatory bowel disease or other benign indications, there is no need to perform a high ligation of the arteries or regional lymphadenectomy.♦ Past surgical history and an abdominal examination may reveal risks that could present challenges to a minimally invasive approach:

Surgical scars and history of adhesions or bowel obstruction may alter port site placement or technique of entry.

Surgical scars and history of adhesions or bowel obstruction may alter port site placement or technique of entry. Several studies have suggested that preoperative bowel preparation is not necessary for elective colon resection. However, the difficulty of manipulating a stool-laden colon laparoscopically and the problems controlling spillage should the colon be violated during resection lead us to recommend formal bowel preparation.

Several studies have suggested that preoperative bowel preparation is not necessary for elective colon resection. However, the difficulty of manipulating a stool-laden colon laparoscopically and the problems controlling spillage should the colon be violated during resection lead us to recommend formal bowel preparation.♦ Formal stoma marking should be made preoperatively if there is a chance that an ileostomy will be created.

Anesthesia

♦ Prophylactic antibiotics are given to cover gram-negative and anaerobic organisms preoperatively. Coverage is extended postoperatively only for special situations.

♦ Prophylactic anticoagulation is used unless there are specific contraindications.

♦ An orogastric tube is placed by anesthesia to decompress the stomach.

Room setup and patient positioning

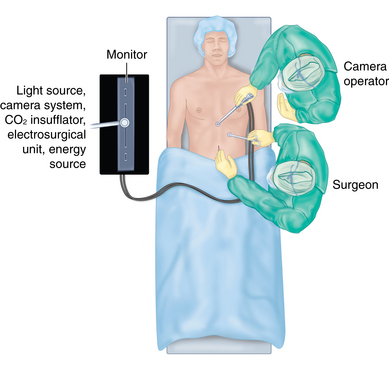

♦ The room setup is depicted in Figure 20-3:

♦ There are a few key features of patient positioning:

Both arms will be tucked in a draw sheet on which the patient lies to help secure the patient to the table; the anesthesiologist may need to adjust oxygen saturation monitoring and IV placement accordingly. Three-inch silk tape or Velcro strips are placed across the chest and lower extremities to help stabilize the patient even when the table is tilted strongly to assist with operative exposure.

Both arms will be tucked in a draw sheet on which the patient lies to help secure the patient to the table; the anesthesiologist may need to adjust oxygen saturation monitoring and IV placement accordingly. Three-inch silk tape or Velcro strips are placed across the chest and lower extremities to help stabilize the patient even when the table is tilted strongly to assist with operative exposure.Step 3. Operative steps

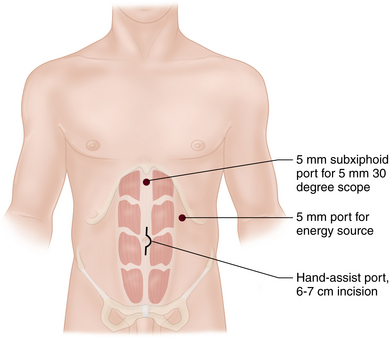

The hand port template is used to demarcate the incision length, which should be no larger than the surgeon’s glove size (e.g., size 7 glove would require a 6- to 7-cm hand port incision).

The hand port template is used to demarcate the incision length, which should be no larger than the surgeon’s glove size (e.g., size 7 glove would require a 6- to 7-cm hand port incision). The hand port incision is centered on the point that is half way between the anterior superior iliac crest and the costal margin. The incision may be quite a bit above the umbilicus in an obese patient.

The hand port incision is centered on the point that is half way between the anterior superior iliac crest and the costal margin. The incision may be quite a bit above the umbilicus in an obese patient. Two additional ports (5 mm each) are placed. The subxiphoid port is placed just to the left of the midline (farther left if an extended right hemicolectomy is anticipated). The left upper quadrant port is placed at the midclavicular line, halving the distance between the costal margin and the superior end of the hand port incision (Figure 20-4).

Two additional ports (5 mm each) are placed. The subxiphoid port is placed just to the left of the midline (farther left if an extended right hemicolectomy is anticipated). The left upper quadrant port is placed at the midclavicular line, halving the distance between the costal margin and the superior end of the hand port incision (Figure 20-4). This is a top down approach. The anatomy is viewed from above and the dissection moves from the right upper quadrant to the right lower quadrant. Mobilization of the anatomy involves lifting the bowel and its mesentery up off of the retroperitoneum.

This is a top down approach. The anatomy is viewed from above and the dissection moves from the right upper quadrant to the right lower quadrant. Mobilization of the anatomy involves lifting the bowel and its mesentery up off of the retroperitoneum. Mobilization of the colon begins in the lesser sac. First, we divide the gastrocolic and hepatocolic ligaments to enter the lesser sac and expose the ventral surface of the transverse mesocolon.

Mobilization of the colon begins in the lesser sac. First, we divide the gastrocolic and hepatocolic ligaments to enter the lesser sac and expose the ventral surface of the transverse mesocolon. Leave the lateral attachments in place initially and expose the rest of the duodenum first by dividing filmy attachments between the ascending mesocolon and duodenum.

Leave the lateral attachments in place initially and expose the rest of the duodenum first by dividing filmy attachments between the ascending mesocolon and duodenum. Divide the lateral attachments of the right colon, carrying the dissection medially along the embryologic fusion plane. Failure to dissect in this avascular plane will result in exposure of the right psoas muscle, ureter, and gonadal vessels. Alternatively, the right kidney may be mobilized or a Kocher maneuver may inadvertently be performed.

Divide the lateral attachments of the right colon, carrying the dissection medially along the embryologic fusion plane. Failure to dissect in this avascular plane will result in exposure of the right psoas muscle, ureter, and gonadal vessels. Alternatively, the right kidney may be mobilized or a Kocher maneuver may inadvertently be performed. Eventually, the entire right colon and ileal mesentery will be elevated off of the retroperitoneum, leaving only the embryologic attachments of the small bowel mesentery attached from the right lower quadrant up to the duodenum. Finally, with the ileal mesentery and small bowel draped into the left lower quadrant, incise the peritoneum at the base of the ileal mesentery from the right lower quadrant back up to the duodenum/ligament of Trietz. This will later allow the ileum to easily come up into the wound for exteriorization and anastomosis. specimen and performing the extracorporeal anastomosis.

Eventually, the entire right colon and ileal mesentery will be elevated off of the retroperitoneum, leaving only the embryologic attachments of the small bowel mesentery attached from the right lower quadrant up to the duodenum. Finally, with the ileal mesentery and small bowel draped into the left lower quadrant, incise the peritoneum at the base of the ileal mesentery from the right lower quadrant back up to the duodenum/ligament of Trietz. This will later allow the ileum to easily come up into the wound for exteriorization and anastomosis. specimen and performing the extracorporeal anastomosis.♦ The lymphovascular pedicles are identified and divided (Figure 20-5):

Find the middle colic vessels near their origin by holding the transverse colon in the palm, elevate it, and use the index finger and thumb to palpate the base of the transverse mesocolon. One or more branches of the MCA will be divided depending on the extent of the resection. A bipolar vessel sealing (device can be used to divide the mesentery and vessels just caudal to the pancreas. Leave a stump of vessel behind in case there is bleeding so that a vascular load of a stapler Endostapler or an Endoloop can be applied.

Find the middle colic vessels near their origin by holding the transverse colon in the palm, elevate it, and use the index finger and thumb to palpate the base of the transverse mesocolon. One or more branches of the MCA will be divided depending on the extent of the resection. A bipolar vessel sealing (device can be used to divide the mesentery and vessels just caudal to the pancreas. Leave a stump of vessel behind in case there is bleeding so that a vascular load of a stapler Endostapler or an Endoloop can be applied. Identify the ileocolic artery sharply to the left of the line of MCA middle colic artery transection.

Identify the ileocolic artery sharply to the left of the line of MCA middle colic artery transection.♦ Desufflate the abdomen through the ports. This is particularly important in cancer resections to avoid seeding port sites with aerosolized tumor cells.

♦ Exteriorize the right colon through the gel port:

♦ Perform an ileocolic anastomosis. This can be done as for conventional open resections. Take care to avoid twisting the ileum, especially if it was divided intracorporally. Return bowel to the abdomen.

♦ Examine the specimen to be sure the target lesion is in the specimen.

♦ Close the incisions. No fascial closure is required for the 5-mm ports. Close the skin with a 4-0 absorbable deep dermal running suture followed by application of a wound sealant.

Step 4. Postoperative care

♦ A fast-track plan is encouraged.

♦ Analgesia. A PCA pump or Toradol with intermittent parenteral narcotics can be used, transitioning promptly to oral analgesics once solid food is started.

♦ Nasogastric tube. This is not routinely used unless there is extensive lysis of adhesions.

♦ Diet. Clear liquids are offered on postoperative day 1 and a soft diet on postoperative day 2 unless the patient has nausea, vomiting, distention, or significant belching.

♦ Urinary catheter. This is removed on postoperative day 1 or 2.

♦ Activity. The patient is encouraged to sit or stand at the bedside the day of surgery and to sit in a chair the morning following surgery. Ambulation is ordered on postoperative day 1.

♦ Discharge. The patient can be discharged once a diet is tolerated and bowel function has resumed. This usually happens by postoperative day 3 to 5.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ The learning curve for laparoscopic colon resection can be shortened by utilizing the hand-assisted approach:

It is estimated that one must perform 25 to 50 pure laparoscopic colon resections to become proficient.

It is estimated that one must perform 25 to 50 pure laparoscopic colon resections to become proficient. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) allows the surgeon to work with less experienced staff. Bowel retraction and vessel identification and division (especially of the middle colic artery) are easier.

Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) allows the surgeon to work with less experienced staff. Bowel retraction and vessel identification and division (especially of the middle colic artery) are easier.♦ The goal of the operation is to perform a safe operation (and a curative operation in the setting of cancer). Patients need a good operation, not necessarily a laparoscopic one.

♦ A periumbilical hand port incision is preferred to a Pfannenstiel incision for several reasons.

♦ Mobilization of the mesocolon around the duodenum should involve gentle, posterior displacement of the duodenum. Care should be taken to avoid mobilization of the duodenum (the Kocher maneuver) to avoid exposure of the porta hepatis and risk of injury to those structures.

♦ Avoid the temptation to ligate the vascular pedicles extracorporally. It’s never possible to reach the mesentery well once bowel is exteriorized, and it’s harder to control bleeding.

♦ Taking at least one branch of the middle colic artery helps assure good length of exteriorized transverse colon and avoid traction injury of the middle colic artery when exteriorizing the bowel.

♦ Leave a short stump of vessel behind when dividing vessels with a vessel sealing and cutting device.

♦ Adhesions in the lesser sac (fusion of the gastrocolic or hepatocolic ligaments with the retroperitoneum or adhesions between the posterior stomach and retroperitoneum) can interfere with adequate exposure of the transverse mesocolon and safe identification of the middle colic artery.

♦ Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery is still image-based surgery. The hand is a sophisticated retraction device.

♦ This procedure safely handles bowel and protects it from the power source.

♦ Manipulation can thin tissue and help identify vessels.

♦ Typically, the index finger leads the way, the next three fingers provide retraction, and the thumb provides countertraction.

Cima RR, Pattana-arun J, Larson DW, et al. Experience with 969 minimal access colectomies: the role of hand-assisted laparoscopy in expanding minimally invasive surgery for complex colectomies. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206;5:946-950. discussion 950-52

Hassan I, You YN, Cima RR, et al. Hand-assisted versus laparoscopic-assisted colorectal surgery: practice patterns and clinical outcomes in a minimally-invasive colorectal practice. Surg Endosc. 2008;22;3:739-743.

Lee SW, Yoo J, Dujovny N, et al. Laparoscopic vs. hand-assisted laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(4):464-469.

Marcello PW, Fleshman JW, Milsom JW, et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic vs. laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51;6:818-826. discussion 826-28

Ringley C, Lee YK, Iqbal A, et al. Comparison of conventional laparoscopic and hand-assisted oncologic segmental colonic resection. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(12):2137-2141.

Stein S, Whelan RL. The controversy regarding hand-assisted colorectal resection. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(12):2123-2126.

Targarona EM, Gracia E, Garriga J, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing conventional laparoscopic colectomy with hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy: applicability, immediate clinical outcome, inflammatory response, and cost. Surg Endosc. 2002;16;2:234-239.

Yamaguchi S, Kuroyanagi H, Milsom JW, et al. Venous anatomy of the right colon: precise structure of the major veins and gastrocolic trunk in 58 cadavers. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45;10:1337-1340.