ANAEMIA

Case vignette

Approach to the patient

History

Examination

Causes of anaemia

Investigations

Management

HAEMATOLOGICAL MALIGNANCIES

MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Case vignette

Approach to the patient

History

Examination

Investigations

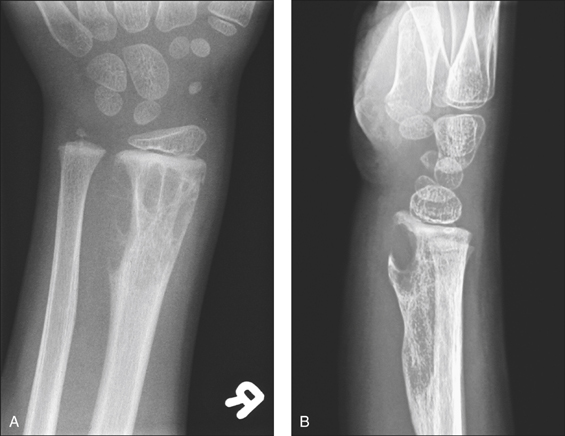

Figure 8.1 Lytic bone lesions: anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of the distal forearm demonstrate an expansile destructive lytic lesion with its epicentre in the diametaphysis of the distal radius which abuts the epiphyseal plate

(reprinted from Kai B, Ryan A, Munk P L et al 2006 Gorham disease of bone: three cases and review of radiological features. Clinical Radiology 61:7).

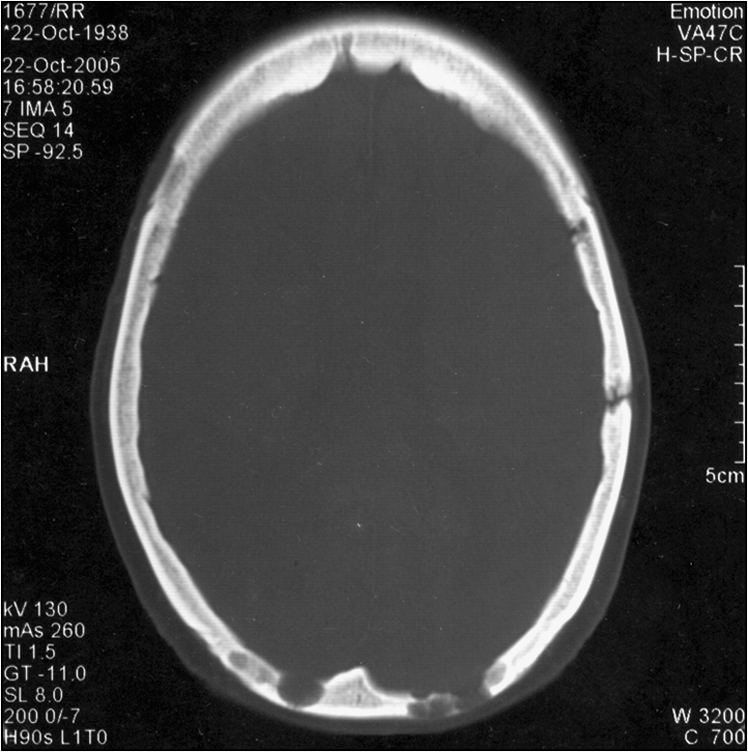

Figure 8.2 Axial CT image of the head in bone window, revealing irregular lytic lesions of the cranial vault in the occipital and left temporal regions

(reprinted from Dinkar A D, Spadigam A, Sahai S 2007 Oral radiographic and clinico-pathologic presentation of Erdheim-Chester disease: a case report. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology 103:5)

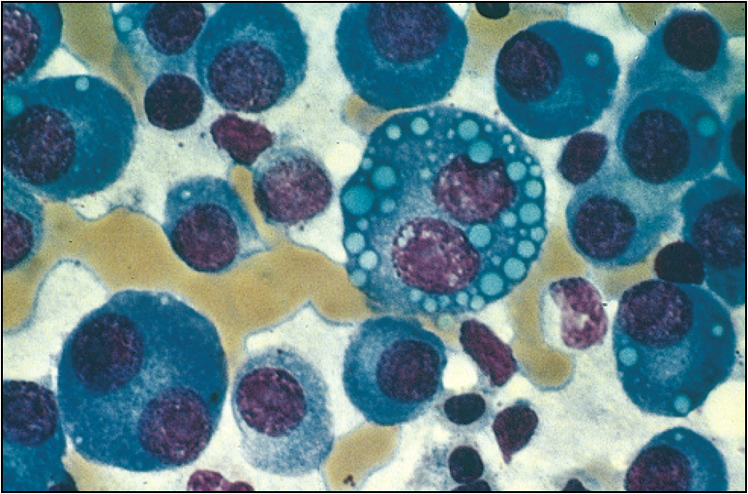

Figure 8.3 Bone marrow film of a myeloma patient

(reprinted from Kumar V, Abbas A K, Fausto N 2005 Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 7th edn. Elsevier, Philadelphia, p 679, fig 14.16)