CHAPTER 56 GYNECOLOGIC INJURIES

TRAUMA IN PREGNANCY

In recent years, trauma has been recognized as the leading cause of death during pregnancy. As unsuspected pregnancy is relatively common in the reproductive years, this possibility must be considered when evaluating female trauma victims. Pregnancy produces significant physiologic and anatomic changes that must be recognized and understood by all health care providers treating pregnant trauma patients (Table 1).

| Change | Consequence |

|---|---|

| Cardiac output and blood volume increase | Shock after >40% of blood lost |

| Expansion of plasma volume | Physiologic anemia |

| Decline in arterial and venous pressure | Vital signs are not reflective of hemodynamic status |

| Increase of resting pulse | |

| Chest enlargement | Change in anatomic landmarks |

| Caution during thoracic procedures (e.g., thoracostomy) | |

| Diaphragm rise | |

| Substernal angle increase | |

| Decrease in functional residual capacity | Rapid decline in PO2 during apnea or airway obstruction |

| Increase in oxygen consumption | |

| Airway closure when supine | |

| Increase in tidal volume and minute ventilation | Fall in PCO2 and bicarbonates |

| Decrease in anesthetic requirements | Need for adjustment of sedative doses |

| Decreased gastric motility | Risk of aspiration |

| Relaxation of gastroesophageal sphincter |

Diagnosis

Prehospital Care

As a result of significant changes in maternal physiology (see Table 1), supplemental oxygen should be administered to prevent maternal and fetal hypoxia during transport and in the resuscitation room. Fluid resuscitation should be initiated even in the absence of signs of hypovolemia and shock. To avoid supine hypotension associated with the uterine compression of the inferior vena cava (IVC), patients in the second or third trimester of pregnancy should be transported on a backboard tilted to the left, with special attention to immobilization of the cervical spine. If the patient is kept in a supine position, the right hip should be elevated 4–6 inches, and the uterus should be displaced manually to the left. This maneuver increases cardiac output by 30% and restores circulating blood volume. Although only about 10% of pregnant patients at term develop symptoms of shock in the supine position, fetal distress may be present even in normotensive mothers; therefore, right hip elevation should be maintained at all times including during operative procedures.

Hospital Care

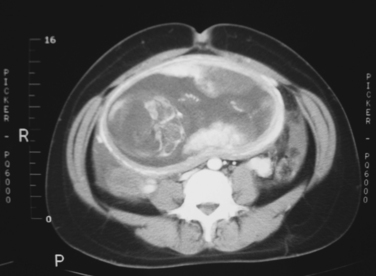

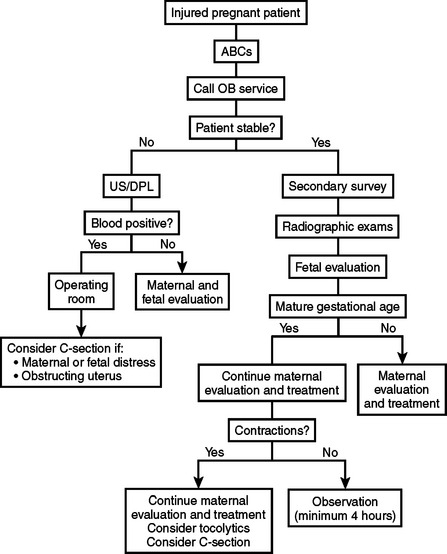

Determination of gestational age is particularly important because this will guide the decision for a premature delivery if indicated. Most institutions will accept a 24–26 week pregnancy as viable, with a probability of survival ranging from 20%–70%. Radiographic estimation of gestational age is bound to an error of 1–2 weeks. Unless the date of the conception is known exactly, gestational age is particularly difficult to determine. A good rule of thumb is to consider patients with a uterus halfway between the umbilicus and the costal margin as having a viable pregnancy (Figure 1). An algorithm for initial maternal and fetal assessment is presented in Figure 2.

Bulging perineum

This is caused most commonly by pressure from extrauterine location of fetal parts.

Abnormal fetal heart rate and rhythm

An abnormal fetal heart rate may be the first indication of a major disruption in fetal homeostasis. During trauma resuscitation, evaluation of the fetus should begin with auscultation of heart tones and continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring (EFM). Any viable fetus of 24 or more weeks gestation requires monitoring after trauma. Cardiotocographic monitoring should be started in the resuscitation room and continued for a minimum of 4 hours; a minimum of 24 hours is recommended for patients with frequent uterine activity (more than six contractions per hour), abdominal or uterine tenderness, ruptured membranes, vaginal bleeding, or hypotension.

Radiographic Examination

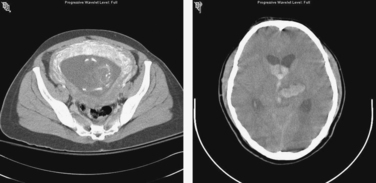

Although there is existing concern about radiation exposure during pregnancy, in most instances the benefits outweigh the risks. It is generally believed that exposure of the fetus to less than 5–10 rad causes no significant increase in the risk of congenital malformations, intrauterine growth retardation, or miscarriage. Radiation doses from common imaging studies are shown in Table 2. All indicated radiographic studies should be performed, as for nonpregnant patients (Figure 3). It is obvious that unnecessary duplication of studies should be avoided.

| Plain anteroposterior chest x-ray | <0.005 rad |

| Pelvic x-ray | <0.4 rad |

| CT scan of head (1-cm cuts) | 0.05 rad |

| CT scan of upper abdomen (20 1-cm cuts) | 3.0 rad |

| CT scan of lower abdomen (10 1-cm cuts) | 3.0–9.0 rad |

CT, Computed tomography.

Abdominal Evaluation

Evaluation of the abdomen in the pregnant patient may be challenging. Superior displacement of the viscera by the expanding uterus changes the anatomical relation of the intra-abdominal organs (Figure 4). Special attention is needed for patients with rib or pelvic fractures, unexplained hypotension, blood loss, hematuria, or altered sensorium caused by drugs, alcohol, or brain injury.

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Organ Injury Scale for gravid uterus is shown in Table 3.

| Grade | Injury Description | AIS-90 Score |

|---|---|---|

| I | Hematoma or contusion without placental abruption | 2 |

| II | Superficial laceration <1 cm in depth or partial placental abruption <25% | 3 |

| III | Deep laceration 1 cm in depth in second trimester or placental abruption 25% but <50%; deep laceration in third trimester | 3–4 |

| IV | Laceration extending to the uterine artery; deep laceration 1 cm with 50% placental abruption | 4 |

| V | Uterine rupture in second or third trimester; complete placental abruption | 4–5 |

Surgical Treatment

Blunt Injury

Pelvic fractures represent the most challenging blunt injuries during pregnancy. Hemorrhage from dilated retroperitoneal veins can cause massive and fatal hemorrhagic shock. Maternal pelvic fracture is the most common cause of fetal death, with a fetal mortality approaching 25%. In nonpregnant patients, angioembolization is the usual treatment for pelvic hemorrhage, but the radiation dose for the procedure is considered excessive during pregnancy.

Penetrating Injury

As the uterus grows and expands out of the pelvis, it becomes an easier target for penetrating trauma. The thick density of its musculature allows the uterus to absorb energy from low-velocity penetrating injuries; maternal death is very uncommon except for injuries in the upper abdomen, which usually produce severe maternal damage. Gunshot wounds cause fetal injuries in 60%–70% of cases, with fetal death in 40%–65%. If the bullet has penetrated the uterus and the fetus is viable, cesarean section is indicated. Indications for C-section at celiotomy are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4 Indications for C-Section during Laparotomy for Trauma

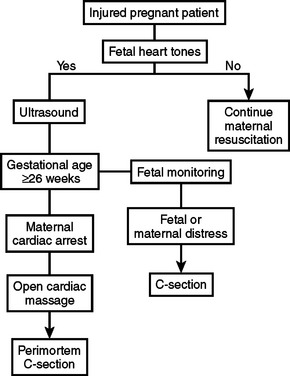

Perimortem C-section is indicated in the case of maternal death if the fetus is viable (24 weeks). Timing is critical, as the probability of fetal survival is excellent when delivery occurs within 5 minutes or less of maternal demise. As the time increases, the chance of survival diminishes. In the rare situation where the mother is declared brain dead but maintains good vital signs, the fetus can be allowed to mature before delivery (Figure 5).

Between gestational age 24–32 weeks, open cardiac massage (OCM) without aortic cross clamping should be seriously considered before an emergency C-section is performed. If OCM proves successful, the delivery may be delayed so that chances of postnatal survival improve. A proposed algorithm for emergency C-section after trauma is presented in Figure 6.

Morbidity and Mortality

Trauma has become the most frequent cause of maternal death in the United States. Older reports attributed 80% maternal mortality to amniotic fluid embolism, which together with pulmonary thromboembolism was cited as the leading cause of maternal mortality. In contrast to declining maternal mortality from infection, hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism, accidental deaths during pregnancy have risen steadily. According to the latest statistics, as many as 36% of maternal deaths are caused by penetrating trauma. While overall maternal mortality from abdominal gunshot wounds is low (3.9%), fetal mortality ranges between 40% and 70%. Risk factors associated with poor fetal outcome are listed in Table 5.

TRAUMA TO NONGRAVID UTERUS AND FEMALE GENITALIA

There is a relative abundance of information on trauma in pregnancy and a relative paucity regarding injuries to the female genitalia. Although these injuries are uncommon in the nonpregnant patient, they are more often seen in cases where there is pathologic enlargement of the internal genitalia or in the early postpartum period. Missed or improperly treated female genital injuries can result in hemorrhage, sepsis, and loss of endocrine and reproductive function.

Diagnosis

Intra-abdominal genital injuries are usually diagnosed at laparotomy for associated injuries. As blunt injury is more common with pathologically enlarged internal genitalia in the nongravid patient, CT scan of the abdomen or DPL may aid the diagnosis, although the latter is very rarely used. Detailed grading of gynecologic injuries is presented in Tables 6 through 10.

| Grade | Injury Description | AIS-90 Score |

|---|---|---|

| I | Contusion or hematoma | 1 |

| II | Superficial laceration involving mucosa | 1 |

| III | Deep laceration extending into submucosal fat or muscle | 2 |

| IV | Complex laceration extending into the cervix or peritoneum | 3 |

| V | Injury to adjacent organs | 3 |

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST).

Modified from Moore EE, Jurkovich GJ, Knudson MM, et al: Organ injury scaling VI: extrahepatic biliary, esophagus, stomach, vulva, vagina, uterus (nonpregnant), uterus (pregnant), fallopian tube, and ovary. J Trauma 39(6):1069–1070, 1995.

Table 7 AAST-OIS for Gynecologic Injuries: Vulva

| Grade | Injury Description | AIS-90 Score |

|---|---|---|

| I | Hematoma or contusion | 1 |

| II | Superficial laceration involving skin only | 1 |

| III | Deep laceration extending into subcutaneous fat or muscle | 2 |

| IV | Avulsion of skin, fat, or muscle | 3 |

| V | Injury to adjacent organs | 3 |

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST).

Modified from Moore EE, Jurkovich GJ, Knudson MM, et al: Organ injury scaling VI: extrahepatic biliary, esophagus, stomach, vulva, vagina, uterus (nonpregnant), uterus (pregnant), fallopian tube, and ovary. J Trauma 39(6):1069–1070, 1995.

Table 8 AAST-OIS for Gynecologic Injuries: Nongravid Uterus

| Grade | Injury Description | AIS-90 Score |

|---|---|---|

| I | Hematoma or contusion | 2 |

| II | Superficial laceration <1 cm in depth | 2 |

| III | Deep laceration 1 cm in depth | 3 |

| IV | Laceration extending to uterine artery | 3 |

| V | Devascularization or avulsion | 3 |

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST).

Modified from Moore EE, Jurkovich GJ, Knudson MM, et al: Organ injury scaling VI: extrahepatic biliary, esophagus, stomach, vulva, vagina, uterus (nonpregnant), uterus (pregnant), fallopian tube, and ovary. J Trauma 39(6):1069–1070, 1995

Table 9 AAST-OIS for Gynecologic Injuries: Fallopian Tube

| Grade | Injury Description | AIS-90 Score |

|---|---|---|

| I | Hematoma or contusion | 2 |

| II | Laceration involving <50% of circumference | 2 |

| III | Laceration involving 50% of circumference | 2 |

| IV | Complete transection | 2 |

| V | Devascularized segment | 2 |

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST).

Modified from Moore EE, Jurkovich GJ, Knudson MM, et al: Organ injury scaling VI: extrahepatic biliary, esophagus, stomach, vulva, vagina, uterus (nonpregnant), uterus (pregnant), fallopian tube, and ovary. J Trauma 39(6):1069–1070, 1995

Table 10 AAST-OIS for Gynecologic Injuries: Ovary

| Grade | Injury Description | AIS-90 Score |

|---|---|---|

| I | Contusion or hematoma | 1 |

| II | Superficial laceration <0.5 cm in depth | 2 |

| III | Deep laceration 0.5 cm in depth | 3 |

| IV | Partial disruption of blood supply | 3 |

| V | Complete parenchymal disruption or avulsion | 3 |

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST).

Modified from Moore EE, Jurkovich GJ, Knudson MM, et al: Organ injury scaling VI: extrahepatic biliary, esophagus, stomach, vulva, vagina, uterus (nonpregnant), uterus (pregnant), fallopian tube, and ovary. J Trauma 39(6):1069–1070, 1995.

1 Petrone P, Asensio JA. Trauma in pregnancy: assessment and treatment. Scand J Surg. 2006;95:4-10.

2 G Desjardins: Management of the injured pregnant patient. Resuscitation. http://www.trauma.org/archive/resus/pregnancytrauma.html

3 Fildes J, Reed L, Jones N, et al. Trauma: the leading cause of maternal death. J Trauma. 1992;32:643-645.

4 Lavery JP, Staten-McCormick M. Management of moderate to severe trauma in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1995;22:69-90.

5 Weiss HB. Pregnancy-associated injury hospitalizations in Pennsylvania, 1995. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:626-636.

6 Weiss HB, Songer TJ, Fabio A. Fetal deaths related to maternal injury. JAMA. 2001;286:1863-1868.

7 Leggon RE, Wood GC, Indeck MC. Pelvic fractures in pregnancy: factors influencing maternal and fetal outcomes. J Trauma. 2002;53(4):796-804.

8 Guth AA, Patcher HL. Domestic violence and the trauma surgeon. Am J Surg. 2000;179:134-140.

9 McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Bullock L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy. Severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA. 1992;267:3176-3178.

10 ACS Committee on Trauma (ACS-COT). Trauma in women. Advanced Trauma Life Support Manual. 6th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 1997.

11 Lavin JPJr, Polsky SS. Abdominal trauma during pregnancy. Clin Perinatol. 1983;10:423-438.

12 Green JR. Placenta previa and abruption placentae. In: Creasey RK, Resnik R, editors. Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1994:604.

13 Sandy EAJr, Koerner M. Self inflicted gunshot wound to the pregnant abdomen: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Perinatol. 1989;6:30-31.

14 Higgins SD. Trauma in pregnancy. J Perinatol. 1988;8:288-292.

15 Selden BS, Burke TJ. Complete maternal and fetal recovery after prolonged cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:346-349.

16 Clark SL, Cotton DB, Pivarnik JM, Lee W, Hankins GD, Benedetti TJ, Phelan JP. Positional change and central hemodynamic profile during normal third trimester pregnancy and postpartum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:883-887.

17 Knudson MM, Rozycki GS, Paquin MM. Reproductive system trauma. In: Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, editors. Trauma. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004:851-875.

18 Eliot G, Rao D. Pregnancy and radiographic examination. In: Haycock CE, editor. Trauma and Pregnancy. Littleton, MA: PSG Publishing; 1985:69-78.

19 Harvey EB, Boice JDJr, Honeyman M, Flannery JT. Prenatal x-ray exposure and childhood cancer in twins. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:541-545.

20 Kaunitz AM, Hughes JM, Grimes DA, et al. Causes of maternal mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:605-612.

21 Wessells H, Aninch J. Injuries to the urogenital tract. In: American College of Surgeons: ACS Surgery Principles and Practice. New York: Web MD; 2005:1080-1085.