Gynaecological and obstetric emergencies

Anatomy and physiology

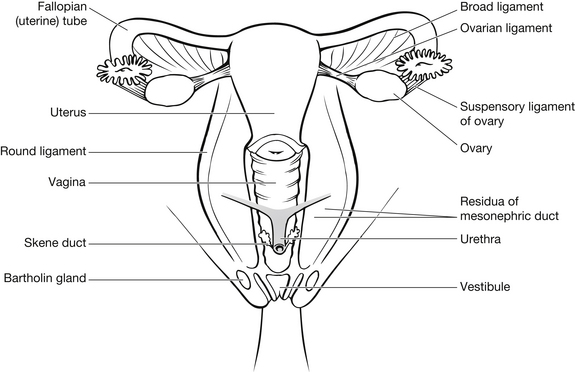

The female reproductive organs consist of:

They are situated outside the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 30.1).

Figure 30.1 The female reproductive system.

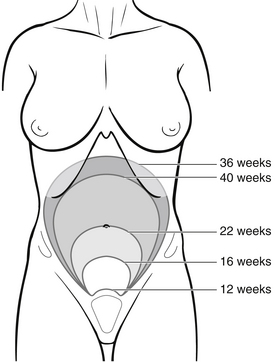

The uterus is located in the anterior pelvis above the bladder. It is a pear-shaped organ with thick walls, made up of three layers: an outer serous membrane, a middle layer of smooth muscle, and the mucosal inner layer of endometrium, which is extremely vascular. The top of the uterus is called the fundus; it is the height of this that is measured to determine the gestation of pregnancy (Fig. 30.2).

Figure 30.2 Change in fundal height during gestation.

The neck of the uterus is called the cervix. This opens into the vagina, the opening of which is called the os. The status of the os is an important consideration in assessing bleeding in early pregnancy. The ovaries sit bilaterally to the uterus, on the lateral pelvic wall, and are connected to the uterus by fallopian tubes. The fallopian tubes have a funnel-like opening below the ovaries, which collects the ova and transports them by peristalsis to the uterus. The tubes are made up of smooth muscle and mucous membrane. The vagina is an elastic tube leading to the external genitalia. There are two small glands either side of the vaginal opening called Bartholin’s glands which can be prone to cyst formation in some women (Bickley & Szilagyi 2003).

During child-bearing years, each ovary is 2.5–5 cm long, 1.5–3 cm wide, and 0.6–1.5 cm thick. Size diminishes significantly after menopause. The number of ova present in the ovaries also decreases with age, from approximately 2 million at birth to 300 000–400 000 by puberty (Sanders Jordan 2009). The female reproductive cycle varies in length between 21 and 35 days, but for most the average cycle is 28 days. The cycle consists of ovulation and menstruation, and is governed by changes in hormone levels. The first 5–7 days of the cycle represent menstruation. This is followed by a 7–8-day follicular phase preparing the endometrium for implantation of a fertilized egg. At around days 14–15 of the cycle, ovulation occurs. Once the ovum is released from the follicle, the luteal phase then commences: the collapsed follicle becomes an endocrine gland called the corpus luteum. It secretes oestrogen and progesterone to support the egg if it is fertilized. If the egg is not fertilized the luteal phase is responsible for the degeneration of the corpus luteum, after which the thickened lining of the endometrium sheds and the cycle begins again. If the egg is fertilized, the corpus luteum continues to secrete hormones until about three months into the pregnancy when the placenta takes over.

Fertilization of the ovum takes place in the fallopian tube, and during the first few days it passes slowly towards the uterus while a series of cell divisions take place forming a mass of embryotic cells. The embryo reaches the uterus between 3 and 5 days after fertilization. It then begins to implant into the uterine wall by about 6–7 days after fertilization. The placenta forms around where the embryo is embedded and, after a few weeks, begins to provide oxygen and nutrients to support fetal growth for the rest of the pregnancy. By five weeks after implantation the fetal heart is pumping well, and nutrients pass from the maternal blood supply across the placental membrane to nourish the fetus.

The pregnancy is divided into trimesters of growth: in the first the internal organs develop; in the second the fetus grows in length and systems begin to mature; and in the last trimester the fetus fattens out and builds up reserves for birth. Physiological changes in pregnancy are plentiful, and an overview of key changes is given in Box 30.1; however, a detailed description is beyond the scope of this text and only those changes related to emergency care in ED will be discussed.

Emergency care of the non-pregnant woman

Obtaining an accurate history is vital to establish the severity of a patient’s condition. Because of the personal nature of gynaecological complaints, the nurse should ensure that assessment is carried out in private and in a sensitive and non-judgemental manner. Box 30.2 highlights the information that should be obtained.

Assessment

General assessment of the woman with a gynaecological condition should include baseline observations of pulse, respiration, blood pressure and temperature to detect signs of shock or infection. The level of pain should be determined, together with the exact location. Gentle abdominal examination will assist in this. If clinically indicated, a vaginal examination should be carried out once, either by the nurse or, more commonly, by the doctor. Assessment should include urinalysis to detect a urinary tract infection as a primary cause of pain. Initially this can be diagnosed by the presence of leucocytes, protein and blood in urine, but culture and sensitivity should follow to ensure appropriate antibiotic therapy. A pregnancy test should also be carried out routinely to exclude unknown pregnancy. Abdominal pain is often the primary reason women with gynaecological complaints attend ED. Conditions causing acute abdominal pain are shown in Box 30.3.

Menstrual pain

Mittelschmerz, from the German ‘middle pain’, is a periodic pain at mid-cycle due to irritation of the peritoneum by follicular fluid at the time of its rupture (Salhan 2011). It should only be diagnosed once other causes, such as ovarian cyst and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), have been ruled out (Reedy & Brucker 1995). The condition is self-limiting, and therefore treatment involves symptom control and education. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, are usually the most effective analgesia. The patient should be made aware of the cyclical nature of the condition, and the possibility of recurrence.

Dysmenorrhoea

In most cases, dysmenorrhoea (period pain) is self-diagnosed and treated at home; however, when symptoms are unusually severe, some women seek emergency care. Two types of dysmenorrhoea exist: primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. In the former, uterine spasm involves A nerve fibres, responsible for acute pain, and C nerve fibres responsible for chronic and referred pain (see also Chapter 25). Primary dysmenorrhoea is most common in adolescents and young women who have not had children (Horne & Critchley 2012).

Diagnosis should be made only after other causes of pain and bleeding have been excluded. Management revolves around symptom control and the condition is self-limiting. NSAIDs are the analgesia of choice because they inhibit intrauterine synthesis of prostaglandin as well as decreasing pain. Small quantities of alcohol are effective in the treatment of dysmenorrhoea because it reduces oxytocin and vasopressor activity, therefore reducing uterine spasm. Ethically, however, this method of pain control should only be advocated for women who understand the potential dangers of alcohol ingestion and are legally old enough to use it (Reedy & Brucker 1995). Discharge information should include the commonality of dysmenorrhoea and, in the case of secondary dysmenorrhoea, information and advice about the predisposing condition.

Ovarian cyst

These usually result from a dysfunction in the menstrual cycle, when a collection of fluid forms around the corpus luteum. Cyst formation is more common in endometriosis and most are benign, self-limiting and asymptomatic. In some instances, the cyst increases in size and becomes symptomatic causing pelvic discomfort at about 8–10 cm diameter due to the stretching of the capsule, although most regress spontaneously over a period of 1–3 months (Sanders-Jordan 2009). Eventually, if growth persists, bleeding, rupture or torsion can occur. Ovarian cysts are uncommon in women using oral contraception.

Management

Cysts not causing haemodynamic compromise tend to be managed conservatively with follow-up investigation from a GP or gynaecological clinic. If adequate pain control cannot be achieved, hospital admission should be considered. If the patient has mild to moderate signs of hypovolaemia, intravenous fluid support should be established, and laparoscopic surgical decompression of the cyst should be considered. In cases of severe hypotension or torsion, fluid resuscitation and urgent surgical intervention are necessary. These women will need both information and psychological support during a time which potentially threatens their fertility.

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Pelvic inflammatory disease comprises a range of upper genital tract inflammatory disorders in women that usually result from microorganisms ascending from the cervix to the upper genital tract (French et al. 2011). Recurrent PID is associated with an increased risk for infertility and chronic pelvic pain (Trent et al. 2011). It is also linked to an increase in ectopic pregnancy. PID is a generic term used to describe infection of the pelvic peritoneum, connective tissue and reproductive organs – most commonly the fallopian tubes (also termed salpingitis). PID results from:

• sexually transmitted infections (STIs), particularly gonorrhoea and chlamydia

For most women, intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCD) are a safe option. Upper genital tract infections occur when pathogenic microorganisms ascend from the cervix and invade the endometrium and the fallopian tubes, causing an inflammatory reaction (Martinez & Lopez-Arregui 2009). Sexually transmitted infections are the most common cause of PID, especially caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The infection occurs in the genital area and spreads along mucosal surfaces, causing transient bouts of inflammation. Infection tends to settle in fallopian tubes, causing scar tissue and adhesions. This makes ovum passage more difficult and increases the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy because the fertilized egg is unable to pass to the uterus and implants in the tube. PID is most common in young women with multiple sexual partners, women who experienced their first sexual intercourse at a young age, or women with a high frequency of sexual intercourse, and within that group PID has a higher incidence in women from lower socioeconomic groups (Bryan 2004). The most common age group is 20–24 years of age (French et al. 2011), which has considerable implications for future healthcare and fertility therapy, as women with PID are at increased risk of chronic pelvic pain, ectopic pregnancy and infertility.

A patient with PID will present with moderate to severe abdominal pain, worse with urination, bowel action and intercourse. Because the pain increases with movement, patients characteristically shuffle, the ‘PID shuffle’. She may be tachycardic and will be pyrexic. If STI is the cause, the patient will have a thick vaginal discharge. If pelvic abscess or peritonitis is developing, the patient will also have nausea or vomiting. Lichtman & Parera (1990) highlighted three grades of PID (Box 30.4).

Management

If the woman is pregnant or has not responded to, or complied with, oral antibiotics, hospital admission should be considered. If the patient is discharged from the ED, it is essential that she has appropriate health education to enable her to recognize a recurrence and get treatment. This is important in reducing potential long-term health problems, including chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia and infertility. If the PID originates from an STI, the patient’s partner should be encouraged to attend an STI clinic and advice should be given about the use of barrier methods of contraception during intercourse. Patients with PID, gonorrhoea, or chlamydial infection should also have serological testing and be offered confidential counselling and testing for HIV infection (Sacchetti 2009).

Bartholin’s cyst

The Bartholin’s glands lie on either side of the vagina and secrete fluid onto the surface of the labia. In normal health these cannot be seen or palpated. If the duct becomes blocked, a small cyst forms; these are usually benign and self-limiting. They can, however, become infected with Escherichia coli or STIs such as gonorrhoea. Bartholin’s cyst/abscess affects 2 % of women (Haider et al. 2007). If infection occurs, the labium becomes inflamed and oedematous to the extent that the patient may have difficulty walking. This is a painful and distressing condition, which is resolved by early excision and drainage of the cyst. This is usually performed as an inpatient procedure. Antibiotic therapy is also indicated (Wechter et al. 2009).

Sexually transmitted infections

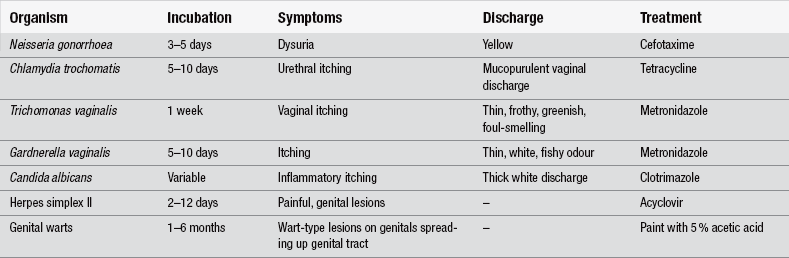

Patients may present to ED because of its relative anonymity compared with GP attendance. Many people are still unaware of the existence and accessibility of STI clinics. Broadly, common symptoms of STI are genital irritation or pain, infection, discharge and sometimes bleeding. Specific symptoms and management are shown in Table 30.1.

The role of the ED nurse in caring for patients with STIs is twofold: first, to provide immediate therapy to resolve the acute episode with appropriate STI clinic follow-up; and second, to provide non-judgemental health education aimed at preventing the spread of STIs. All direct sexual contacts of the patient should be advised to have a health check. It is not possible for the ED nurse to personally follow up patient contacts, but the nurse can support the patient in informing a current partner, and information can then be cascaded to anyone else who may be involved. Patients should refrain from sexual activity until the infection is clear. Advice about barrier contraception should also be given and where appropriate, opportunities for serological testing, confidential counseling and testing for HIV infection (Sacchetti 2009).

Emergency contraception

Progesterone-based pills

The most widely used emergency contraception is that containing levonorgestrel. While it was initially prescribed in two divided doses, a single dose is now the preferred method of administration (Black 2009). Administration of the drug which should be taken within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse. Nausea and vomiting are significant side-effects of oral postcoital contraception and some doctors prefer to prescribe prophylactic anti-emetic drugs with the pill. Follow-up care should be sought around three weeks after postcoital contraception. It is because these facilities are not available in ED that some consultants choose not to offer emergency postcoital contraception. Most women will commence menses within 21 days of the postcoital pill. If this does not happen, a pregnancy test should be performed; however, the failure rate of the postcoital pill is less than 2 % if taken within 72 hours of coitus (Task Force on Postovulatory Method of Fertility Regulation 1998).

Intrauterine contraceptive device

The IUCD may be used up to five days after ovulation, or after unprotected intercourse if the date of ovulation is not known. It also works by preventing implantation, and failure is rare at 0–0.2 % (Black 2009). There are disadvantages to its use in nulligravida women because of pain associated with insertion. It is not ideal for women with existing pelvic infection as it could exacerbate this. Irregular vaginal bleeding is also common after IUCD insertion. The advantage of this method is that it provides longer-term contraception. The use of prophylactic antibiotics may be considered for women who are at increased risk of sexually transmitted infection if an IUCD is to be inserted before results of tests are available (French et al. 2004).

Rape and sexual assault

In England and Wales, under the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (Home Office 2003), the definition of rape is the non-consensual penetration of vagina, mouth or anus by a penis. Sexual assault by penetration is the non-consensual, intentional insertion of an object other than the penis into the vagina or anus. The Act also treats any sexual intercourse with a child under the age of 13 as rape and defines the age of consent as 16 (College of Emergency Medicine 2011).

Rape and sexual assault are violent crimes. Police forces are increasingly caring for physically injured survivors of rape in dedicated rape suites equipped for the privacy and comfort of women who have been assaulted. In the UK and Ireland, Sexual Assault Referral Centres (SARCs)/Sexual Assault Treatment Units (SATUs) are located at most major hospitals providing an integrated response to adult survivors of rape and sexual assault. The services provided include forensic and medical examination, one-to-one counselling, screening for sexually transmitted diseases, postcoital contraception and 24-hour information and support (Lovett et al. 2004, Lovett & Kelly 2009). Specialist Forensic Nurses trained in the collection of forensic evidence, photo documentation and legal testimony ensure high standards of practice are maintained. Thorough, compassionate assessment and treatment of survivors, as well as the meticulous collection and documentation of forensic evidence, are vital for successful prosecution (Fitzpatrick et al. 2012).

These clinicians are dedicated to the care of survivors of sexual and domestic violence, liaising with medical and nursing staff, police social services and support agencies (Markowitz et al. 2005).

There were 54 509 sexual offences recorded by the police in England and Wales in 2009/10; however, police-recorded statistics on sexual offences are likely to be more heavily influenced by under-reporting than the British Crime Survey (BCS) and therefore should be interpreted with caution (Flately et al. 2010). Analysis of the 2007/08 BCS self-completion module showed that 11 % of victims of serious sexual assault told the police about the incident (Povey et al. 2009).

The decision to report sexual assault is entirely that of the patient, and ED staff must support that decision and plan care around it. Box 30.5 shows care paths for reporting and non-reporting of sexual assault. If the patient does not have significant physical injury, it may be appropriate to obtain a full history jointly with the police if the patient wishes to report the attack. This is simply to prevent the patient having to describe the incident several times, which can be unnecessarily distressing. The decision to take a joint history should be the patient’s. Box 30.6 highlights the essential information needed.

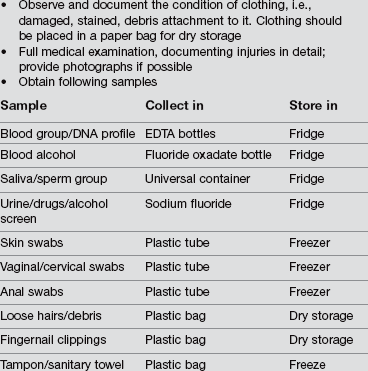

It is important that any potential forensic evidence is preserved. This is equally important in a patient who is unconscious or who has significant physical injury; however, treatment of associated immediate life-threatening injuries takes priority over forensic examination. A paper sheet should be placed under the patient to collect debris if possible; otherwise linen used should be saved. A mobile patient should be asked to stand on a paper sheet while undressing so that debris can be saved. If unconscious, the paper couch liner should be retained also. Wet or blood-stained garments should not be put into a plastic bag as this will lead to decomposition rendering forensic analysis very difficult. The responsibility to collect evidence and maintain the chain of evidence resides with the police and a forensic medical examiner (College of Emergency Medicine 2011). Physical examination should be carried out at once by a forensic medical examiner (FME).

In some areas, the FME will take on this role whether or not the patient intends to prosecute, although Kelly (2002) notes that the vast majority of survivors, both female and male, express a preference for a female forensic examiner. The first priority must lie in protecting the patient from further humiliation and distress and, on those grounds alone, one examination is good practice. For evidence to be submissible in court, the examination, evidence collection and documentation should follow local police policy. The primary role of the ED nurse is in supporting the patient and ensuring her privacy and safety until examination can take place. Box 30.7 shows what evidence should be collected and how it should be preserved.

Once the medical examination has been carried out, the patient needs to be advised about pregnancy risk and offered emergency contraception if appropriate. The patient should also be offered follow-up STI screening and it is imperative she has either actual contact with a rape survivors’ support counsellor or contact telephone numbers for later use should she wish to do so. Rape trauma syndrome (RTS) is experienced by most sexual assault survivors in some form (Burgess & Holmstrom 1974, McGrath 2010). Good, sensitive, non-judgemental care immediately following the attack can help to reduce the impact of RTS. It is important that ED nurses understand the progression of this syndrome, both for immediate care of attack survivors and to help recognize and rationalize associated symptoms of patients sometime after the assault. Box 30.8 outlines the stages of RTS.

Domestic violence refers to the use or threat of physical, sexual or emotional force by spouses, partners, relatives or anyone else with a close relationship with their victims. It occurs among people of all social classes, age groups, ethnic groups and cultures; among disabled and able-bodied people; and in homosexual and heterosexual relationships (Kearns et al. 2008, Gibbons 2011). Domestic violence can involve slapping, kicking, hitting, punching, burning or scalding, use of weapons or destruction of property; it often results in injury and can lead to death (Boursnell & Prosser 2010). There are a number of tell-tale signs of domestic abuse of which emergency nurses should be aware (Health Service Executive 2007, Gibbons 2011) (see Box 30.9).

Based on findings of the BCS of 22 643 women and men aged 16–59 years, Walby & Allan (2004) found that inter-personal violence is both widely dispersed and it is concentrated. It is widely dispersed in that some experience of domestic violence (abuse, threats or force), sexual victimization or stalking is reported by over one-third (36 %) of people. It is concentrated in that a minority, largely women, suffer multiple attacks, severe injuries, and experience more than one form of inter-personal violence and serious disruption to their lives.

The practice of efficient patient processing in EDs may obscure subtle signs of abuse, which may not be picked up until the woman presents with more serious physical injuries (Olshansky 2002). The confidential enquiry into maternal deaths (Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health 2004) found that 14 % of the women whose deaths were assessed had a history of domestic violence which was either self-reported to healthcare professionals or was known to health and social services. This is believed to be a conservative estimate of the true prevalence of violence among these women, and ED nurses should be vigilant to the signs of abuse and the local services available to these patients.

Emergency care of the pregnant woman

As with other aspects of healthcare, an accurate history of events leading to ED attendance is imperative. In the case of a pregnant patient, a full obstetric history should be obtained as well as the history of the presenting complaint. Box 30.10 highlights the information needed for an obstetric history.

Miscarriage

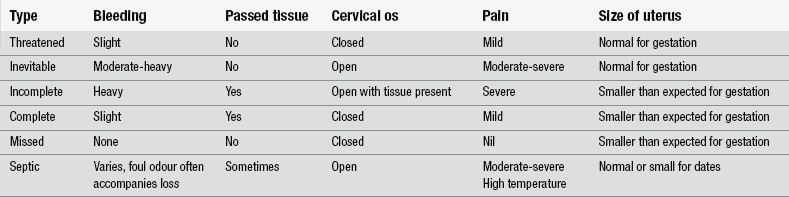

Miscarriage is also termed ‘spontaneous abortion’ and describes the delivery of a non-viable fetus before 24 weeks’ gestation. There are six types of miscarriage and these are listed in Table 30.2.

Marquardt (2011) notes that women with threatened miscarriage can present at any point during the first 24 weeks of pregnancy and half of them will progress to actual miscarriage (Dighe et al. 2008). Patients may or may not report pain that is similar to period pain or cramps. This is due to the contraction of the uterus in response to irritation caused by the bleeding. In women with threatened miscarriage, the cervix is likely to be closed. In inevitable miscarriages, the os is usually open, due to dilation and there has been a partial loss of products of conception, which can be seen or felt through the os. Inevitable miscarriages present as complete miscarriages, in which all products of conception are passed, or as incomplete miscarriages, in which some products are retained (Wyatt et al. 2012). Where there is complete miscarriage the cervical os is closed and the uterus is small and contracted.

Where a cause is investigated, pathological abnormalities with the fetus or placenta are commonly found. Immunological incompatibility with the father, maternal infection, substance misuse and malnutrition have also been linked with spontaneous abortion (Reedy & Brucker 1995).

Despite the relative commonness of miscarriage, it can be devastating for the woman and her partner. Apart from the physical pain associated with miscarriage, the woman and her family are grieving for the loss of a baby, the dreams and plans they will have had for that baby, and their identity as a family. It is essential that ED nurses recognize the enormity of this loss and do not attempt to trivialize it with comments like ‘you can have another’, or by functional care avoiding conversation about the miscarriage. Parents want their loss acknowledged and it is much better for the nurse to express condolences for the loss of their baby (Olga & van den Akker 2011).

Management

In most cases of miscarriage, ED care revolves around symptomatic management and psychological support. If the patient shows signs of hypovolaemia, intravenous fluid replacement should be commenced. Adequate analgesia should be given, particularly if the pregnancy is not viable. If the miscarriage has been an incomplete or missed abortion, the patient should be prepared physically and emotionally for an evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPC) in theatre. Psychological support for both the woman and her partner is important throughout their stay in ED, as the initial handling of their loss will impact on the grieving process they must work through (see also Chapter 14).

The use of the term ‘spontaneous abortion’ should be avoided at this time, as many people associate abortion with voluntary termination of pregnancy. Miscarriage, on the other hand, is seen as involuntary. Using the term abortion can therefore cause unnecessary distress (Olga & van den Akker 2011).

Ectopic pregnancy

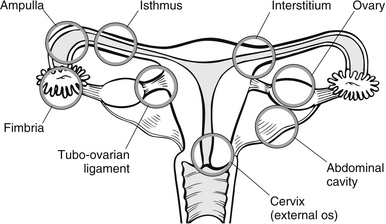

The word ectopic comes from the Greek word for ‘out of place’. Ectopic pregnancy (EP) describes any pregnancy implantation outside of the uterine cavity. Classification of EPs can be broadly divided into two main categories, tubal and non-tubal. The vast majority of EPs are tubal (95 %). Although non-tubal EPs make up only 5 % of all EPs, these disproportionately contribute to the morbidity and mortality associated with EPs (Winder et al. 2011) (Fig. 30.3). It is also an important cause of first trimester morbidity and mortality and accounts for 80 % of first trimester maternal deaths (Lewis 2011), and EP currently accounts for 1 % of all pregnancies (Winder et al. 2011).

Figure 30.3 Sites of implantation of ectopic pregnancies.

A diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy should be considered in all women of childbearing age presenting with abdominal pain or an unexpected collapse (Moulton & Yates 2004). This ratio has risen over the last decade and indications are that it will continue to rise with the increase in PID and IUCD use (Shennon 2003).

The use of oral postcoital contraceptives and some fertility treatments also appear to increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy. Ectopic implantation appears to occur because of delay in passage of the fertilized egg. This passage is induced by muscular contraction and ciliary activity. If the fallopian tubes are damaged due to adhesions following infection, the ciliary activity is reduced and the egg cannot pass into the uterus, so it implants in the tube. Hormonal changes of the corpus luteum continue as, physiologically, the pregnancy is still viable at this stage. As a result, the uterus grows and softens as it would with a normal uterine pregnancy. The products of conception continue to expand, causing pain and vaginal bleeding in a ’spotting’ form. It is usually at this stage that the woman seeks health intervention. If left unchecked, the products of conception will continue to grow until rupture of the tube occurs and devastating haemorrhage follows (Fig. 30.3).

Assessment

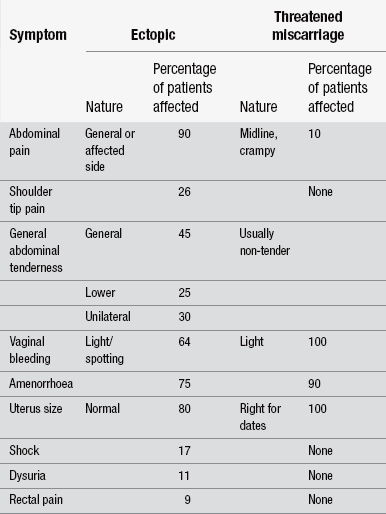

Most patients will give a history of abdominal pain, sometimes unilateral or generalized lower abdomen and pelvic pain. The patient usually has intermittent vaginal bleeding or spotting and, as a result, may or may not be aware that she is pregnant. Most embryos die within 6–12 weeks of gestation due to lack of placental development. For this reason, most women with ectopic pregnancy suffer a lot less nausea than those with a uterine pregnancy with a healthy developing placenta. Once the embryo dies, endometrium is shed and a large PV bleed ensues. This is different to the potentially life-threatening haemorrhage that occurs with a ruptured fallopian tube. The degree of haemodynamic compromise determines the urgency of intervention, and therefore accurate assessment of basic haemostasis is vital. Slight tachycardia would be expected because of the emotion and anxiety attached to ectopic pregnancy, but bradycardia together with an increase in respirations and postural and persistent hypotension should be treated seriously. As part of the assessment, a urine and blood sample should be taken for serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) testing to confirm pregnancy, and a transvaginal ultrasound scan will show the location of pregnancy after about five weeks’ gestation. Table 30.3 highlights the clinical differences between a threatened miscarriage and an ectopic pregnancy.

Table 30.3

Differential diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy vs. threatened miscarriage (after Stevens & Kenney 1994)

(After Stevens L, Kenney A (1994) Emergencies in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.)

Management

Early management revolves around symptom control and psychological support. Pain relief and routine intravenous access should be established via two large-bore cannulas. Blood samples are sent for group and cross-match, beta hCG, full blood count and coagulation studies. If the woman demonstrates signs of shock, fluid replacement should commence. Once the diagnosis has been made, using transvaginal/abdominal ultrasound and blood/urine hCG levels, treatment is prescribed dependent on the patient’s haemodynamic status and gestation of pregnancy. In most instances, both haemodynamically stable and unstable patients can be managed by laparoscopy (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2004).

Medical management of ectopic pregnancy reduces the need for surgical intervention in women who are haemodynamically stable and at an early stage of the pregnancy. This involves the use of cytotoxic intramuscular methotrexate, two dose regimen (Barnhart 2009), administered using special safety precautions for its preparation, administration and disposal. As the embryo is one of the fastest growing cells in the body the proliferating trophoblastic tissue is very sensitive to the action of methotrexate, causing cell death and dissolution. Close monitoring of beta hCG levels by the gynaecological team is required to ensure this treatment has been successful (Miller & Griffin 2003). Local injections of prostaglandins and laparoscopic injections of hyperosmolar glucose solutions have also been used successfully with fewer side-effects. Conservative surgical management involves the removal of the conceptus via laparoscopic salpingostomy, conserving the fallopian tube. In cases where the conceptus has implanted within the fimbrial region of the fallopian tube, fimbrial evacuation may be considered. These procedures carry an increased risk of future ectopic pregnancies because of scarred tissue. If salpingostomy is not possible, the fallopian tube is removed to prevent tubal rupture, with obvious implications for future fertility.

As the mortality rate for deaths from ectopic pregnancy continues to rise, the confidential enquiry into maternal and child health 2000––2002 found that of those who died as a result of ectopic pregnancy, 66 % were assessed as having had some form of substandard care. As a result the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2004) set out recommendations for EDs. They advised that ectopic pregnancy should be excluded in all women of childbearing age with unexplained abdominal pain. Furthermore all clinicians, including undergraduate medical and nursing students, need to be made aware of the typical and atypical presentations of ectopic pregnancy and how it may mimic gastrointestinal disease (Lewis 2011).

Pre-eclampsia/eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia, or pregnancy-induced hypertension, complicates about 10 % of all pregnancies and is associated with increased risk of adverse fetal, neonatal and maternal outcomes, including preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction, perinatal death, acute renal or hepatic failure, antepartum haemorrhage, postpartum haemorrhage and maternal death (Steegers et al. 2010). Worldwide, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia is one of the three leading causes of maternal morbidity and mortality (Ghulmiyyah & Sibai 2012).

Its causes have not been proven, however, pre-eclampsia is known to have hereditary elements (Williams & Broughton Pipkin 2011). Other theories link eclampsia to a possible immunological cause where an antigenic reaction to the fetus causes maternal symptoms. Historic linkage of eclampsia to socioeconomic status has no foundation in research. Women most susceptible to pre-eclampsia/eclampsia are those at either end of the child-bearing age range, i.e., younger than 16 or older than 35 years of age. It is most common in first pregnancies and in those women expecting twins or more, and there appears to be a familial link. Women with pre-existing health problems, such as diabetes and chronic hypertension, are more susceptible to pre-eclampsia.

The disease usually has a gradual onset, the pre-eclampsia phase. Because of good antenatal screening, most patients are identified and treated early. Therefore, the use of ED for care in the pre-eclampsic phase is uncommon, but it is important to understand the disease process in order to treat life-threatening eclampsia in ED. Pre-eclampsia has a multisystem impact (Box 30.11).

Pre-eclampsia

• hypertension – 30 mmHg or more above the woman’s usual systolic BP or 15 mmHg above her usual diastolic BP

• oedema – where this is present in the face or upper limbs it is of greater concern. Lower limb oedema, particularly of the feet or ankles, is usually mechanical in nature.

If any two of these symptoms are present, the woman is considered to have pre-eclampsia. Persistent hypertension should be treated, and initially close maternal and fetal monitoring will necessitate admission.

Eclampsia

This is usually defined as the onset of seizures in pregnancy occurring after 21 weeks’ gestation or within 10 days of delivery. It is accompanied by at least two of the following signs: hypertension, proteinuria and oedema. Later signs include thrombocytopenia of raised aspartate amino transferase. Eclampsia is one of the main causes of maternal deaths, occurring in approximately 1 in 2000 pregnancies (Munro 2000). Prior to fitting, most patients complain of headache, visual disturbance, shortness of breath or right hypochondriacal pain. They may also have oliguria and appear confused. These symptoms are all derived from the physiological processes described in Box 30.11. While some women present to the ED at this stage, more appear as emergency admissions once fitting has commenced. Staff should be alert to the possibility of a concealed pregnancy in young women who have no previous history of seizures. Eclampsic fitting is life-threatening to both the mother and fetus. It must be brought under control rapidly using small doses of diazepam, 10 mg i.v. repeated up to five times. It is administered in this manner to prevent fetal depression. Intravenous infusion of chlormethiazole or phenytoin should also be considered. Occasionally, short-term ventilation and paralysis may be necessary. Other presentations of impending eclampsia include severe right hypochondriacal pain and shock as a result of hepatic rupture.

Urgent laparotomy is indicated to control haemorrhage and preserve maternal life. In these circumstances, however, it has a mortality of about 70 %. Symptoms of disseminating intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) accompany about 7 % of eclampsic conditions (Stevens & Kenney 1994). Once pre-eclampsia reaches this stage, or fitting has occurred, urgent preparation to deliver the fetus should be made. Delivery usually resolves maternal symptoms, although in some cases they may persist for up to 10 days (Reedy & Brucker 1995). The baby has a greater chance of survival even if delivered premature.

Abruptio placentae

This is more commonly treated in obstetric units than in EDs. It occurs as a result of premature separation of the placenta from the uterine wall and is an obstetric emergency and is a major risk factor for foetal and perinatal mortality and morbidity (Jabeen 2010). Haemorrhage and blood usually track between the uterus and placental membranes, causing PV bleeding and pain. Bleeding can be occult in about 10 % of cases, and therefore diagnosis should not be made simply by the presence of PV bleeding. A pelvic ultrasound should be used to confirm diagnosis. Predisposing factors include substance misuse, pre-eclampsia, a maternal age of 35 or more, multiple gestation and as a result of trauma.

Emergency childbirth

The majority of births are normal deliveries requiring little assistance and the duration of labour is usually long enough for the woman to seek maternity care. Occasionally, however, it is necessary to deliver a baby in the ED if there is insufficient time to reach the delivery unit. The most common causes of emergency childbirth include multiparous women with precipitous (rapid) deliveries and adolescent girls who successfully conceal their pregnancy until they present with abdominal pains or do not recognize the signs of active labour. Some women in pre-term labour may also have precipitous deliveries. Child protection issues may be raised in cases where a woman whose child may be at risk may choose to avoid traditional routes of maternity care and travel to a hospital outside of their area, presenting to EDs in labour (McLoughlin 2001).

Labour can be described as a process by which the fetus, placenta and membranes are expelled through the birth canal. Normal labour begins spontaneously at approximately 40 weeks’ gestation, referred to as ‘term’, with the fetus presenting by the head or ‘vertex’. Box 30.12 outlines the stages of labour.

First-stage labour management

The nurse’s role in the care of a woman facing imminent childbirth is to provide physical and emotional support in a calm, relaxed manner (McCormack 2009). The nurse should obtain enough information to assess the woman’s immediate circumstances:

• at what gestation is the pregnancy?

• what signs of onset of labour has she experienced?

The assistance of a midwife, obstetric and neonatal team should be obtained immediately, and provision for the imminent birth should be made. Signs of imminent childbirth include:

• the mother experiences tension, anxiety and intense contractions

• blood ‘show’ as a result of rapid dilation of the cervix

• bulging or gaping of the anus as a result of descent of the fetal presenting part

• bulging or fullness of the perineum

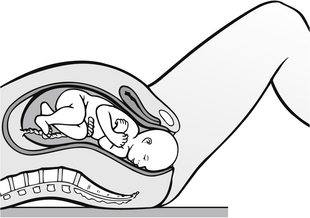

• ‘crowning’ of the fetal head at the introitus, which occurs when the fetal skull escapes under the pubic arch and no longer recedes (Fig. 30.4)

Figure 30.4 Cross-sectional view of crowning.

In multiparous women, the last sign is symptomatic of imminent birth; however, in primiparous women, birth may take up to 30 minutes. Birth is near when the head stays visible between contractions. The mother should be made to feel in control, protecting her dignity, and should be kept informed of all that is happening. Her partner should be included as a source of constant support and encouragement to the mother at this time. The mother should be encouraged to adopt a position which is most comfortable for her, which is usually sitting on the trolley with her back well supported with pillows or a foam wedge. Nitrous oxide is the preferred method of pain relief when birth is imminent and the mother should be encouraged to inhale the gas while she is feeling the contractions. As well as providing pain relief, it is also an effective means of providing extra oxygen to both the mother and the fetus. Neither shaving, urinary catheterization nor enema administration are required (Priestly 2004).

Second-stage labour management

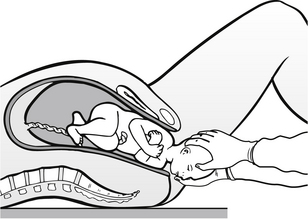

The attending nurse/midwife should open a sterile delivery set and wash the woman’s vulva with sterile swabs and warmed antiseptic solution. With the next contraction, the woman should be encouraged to inhale deeply and bear down to facilitate the delivery. The nurse should place his/her fingers over the advancing head to prevent expulsive ‘crowning’, which may result in perineal tearing and a heightened risk of intraventricular haemorrhage to the newborn infant (Fig. 30.5). As the fetal head advances and gradually distends the perineal tissue, the mother should be encouraged to pant to facilitate a controlled delivery and reduce maternal trauma. Once the baby’s head emerges, the nurse should slip a finger over the occiput to feel if the cord is round the baby’s neck. If this has happened, the cord should be released either by slipping it over the head or, if this is unsuccessful, by applying two artery forceps 2–5 cm apart and cutting the cord between them.

Figure 30.5 Hold infant’s head gently in both hands.

The nurse should continue to support the head, taking care not to put any traction on it (Fig. 30.6). Mucus should be removed with a sterile swab, but the eyes should not be cleansed due to the risk of infection. At the next contraction, the anterior shoulder should be delivered by gentle downward traction of the head. Then the baby should be raised and the posterior shoulder will deliver rapidly, followed by the trunk and legs. The baby should be dried and placed in a warm towel, as a cold baby has an increased oxygen consumption and cold babies more easily become hypoglycaemic and acidotic; they also have an increased mortality (Advanced Life Support Group 2011). The newborn baby should be allowed to lie on the bed or be placed on the mother’s abdomen, allowing her to see and touch the baby. The umbilical cord should be clamped and cut if this has not already been done and syntometrine given intramuscularly to the mother. This contains oxytocin and ergometrine. The oxytocin provides marked uterine contraction after approximately three minutes but is short-lived, and as its effects begin to wear off the ergometrine begins to act and provide longer-lasting uterine contractions, reducing the risk of postpartum haemorrhage.

Figure 30.6 Carefully support infant’s head as it is born.

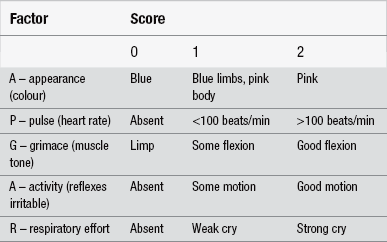

The time of the delivery and those involved in it should be recorded accurately. The Apgar score should also be recorded. This is a numerical scoring system used to assess the newborn baby’s condition at one minute after birth and reassessed again after five minutes. The factors assessed are heart rate, respiratory rate, muscle tone, reflex response to stimulus, and colour (Finster & Wood 2005). A score of 0–2 is given to each sign in accordance with the guideline in Table 30.4. A normal infant in good condition at birth will achieve an Apgar score of between 7 and 10. A score below 7 indicates some degree of asphyxia which requires some form of resuscitation.

Postpartum haemorrhage

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a major cause of maternal deaths around the world. The incidence of PPH is between 2 and 11 % (Oyelese et al. 2007, Lombaard & Pattinson 2009). It can be described as any bleeding from the genital tract that adversely affects the mother’s condition following the birth of a baby, up to 6 weeks post-delivery. A blood loss of 500 mL or more at delivery is regarded as PPH, irrespective of maternal condition. There are two types of PPH:

• primary PPH, which occurs within the first 24 hours post-delivery

• secondary PPH, which occurs at any time after the first 24 hours, up to 6 weeks post-delivery, but most commonly occurs between 7 and 14 days postpartum. It can be described as bleeding in excess of the normal lochial loss and may be associated with retained placental tissue or uterine infection.

Assessment

History should include the following information:

• quantity of bleeding in terms of number of pads used per hour

• type of blood loss, i.e., red, brown clots

The woman will have an enlarged, ‘boggy’, uterus. On palpation the uterus will feel soft, distended and lacking in tone. The fundal height will rise above the umbilicus as a result of retained blood in the uterus preventing uterine contraction. A low-grade pyrexia, rising pulse and falling blood pressure characterize postpartum haemorrhage, together with lower back and abdominal pain, and general restlessness.

References

Advanced Life Support Group. Advanced Paediatric Life Support: The Practical Approach. Wiley-Blackwell: West Sussex; 2011.

Barnhart, K.T. Ectopic pregnancy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(4):379–387.

Bickley, L.S., Szilagyi, P.G. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking, eighth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

Black, K.I. Developments and challenges in emergency contraception. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2009;223(2):221–231.

Boursnell, M., Prosser, S. Increasing identification of domestic violence in emergency departments: a collaborative contribution to increasing the quality of practice of emergency nurses. Contemporary Nurse. 2010;35(1):35–46.

Bryan, S. Pelvic inflammatory disease. In Cameron P., Jelinek G., Kelly A.M., Murray L., Brown A.F.T., Heyworth J., eds.: Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine, second ed, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

Burgess, A., Holmstrom, L. Rape: Victims of Crisis. Maryland: RJ Brady; 1974.

College of Emergency Medicine. Management of Adult Patients who attend Emergency Departments after Sexual Assault and/or Rape. London: College of Emergency Medicine; 2011.

Confidential Enquiry into Maternal, Child Health. Maternity Services in 2002 for Women with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes, England, Wales and Northern Ireland. London: CEMACH; 2004.

Dighe, M., Cuevas, C., Moshiri, et al. Sonography in first trimester bleeding. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. 2008;36(6):352–366.

Finster, M., Wood, M. The Apgar Score has survived the test of time. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:855–857.

Fitzpatrick, M., Ta, A., Lenchus, J., et al. Sexual assault forensic nurses’ training and assessment using simulation technology. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2012;38(1):85–90.

Flately, J., Kershaw, C., Smith, K., et al. Crime in England and Wales 2009/10. London: Home Office; 2010.

French, C.E., Hughes, G., Nicholson, A., et al. Estimation of the rate of pelvic inflammatory disease diagnoses: Trends in England, 2000–2008. Sexual Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38(3):158–162.

French, K., Ward, S., McRae, J., et al. Emergency contraception. Nursing Standard. 2004;18(42):49–53.

Ghulmiyyah, L., Sibai, B. Maternal mortality from preeclampsia/eclampsia. Seminars in Perinatology. 2012;36(1):56–59.

Gibbons, L. Dealing with the effects of domestic violence. Emergency Nurse. 2011;19(4):12–17.

Haider, Z., Condrus, G., Kirk, E., et al. The simple outpatient management of Bartholin’s abscess using Word catheter: A preliminary study. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;47(2):137–140.

Health Service Executive. Domestic Abuse Guidelines for Hospital Staff. Dublin: HSE; 2007.

Holloway, M. Care of the sexually assaulted woman. Emergency Nurse. 1994;2(3):18–20.

Home Office. Sexual Offences Act. London: HMSO; 2003.

Horne, A.W., Critchley, H.O.D. Menstrual problems: Heavy menstrual bleeding and primary dysmennorrhoea. In Edmonds D.K., ed.: Dewhurst’s Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, eighth ed, London: John Wiley and Sons Ltd., 2012.

Jabeen, M. Abruptio placentae: Risk factors and perinatal outcome. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine Institute. 2010;18(4):669–676.

Kearns, N., Coen, L., Canavan, J. Domestic Violence in Ireland: An Overview of National Strategic Policy and Relevant International Literature on Prevention and Intervention Initiatives in Service Provision. Galway: Child and Family Research Centre; 2008.

Kelly, L. A Research Review on the Reporting, Investigation and Prosecution of Rape Cases. London: HMCPSI; 2002.

Lewis G (ed). (2011) Saving Mothers’ lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer – 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 118 Supp 1, 1–205

Lichtman, R., Papera, S. Gynecology: Well Woman Care. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1990.

Lombaard, H., Pattinson, R.C. Common errors and remedies in managing postpartum haemorrhage. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2009;23:317–326.

Lovett, J., Kelly, L. Different Systems, SImilar Outcomes: Tracking Attrition in Reported Rape Cases Across Europe. London: London Metropolitan University; 2009.

Lovett, J., Regan, L., Kelly, L. Sexual Assault Referral Centres. Developing Good Practice and Maximising Potentials: Home Office Research Study 285. London: Home Office; 2004.

Markowitz, J.R., Steer, S., Garland, M. Hospital-based intervention for intimate partner violence victims: a forensic nursing model. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2005;31(2):166–170.

Marquardt, U. Management of miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy. Emergency Nurse. 2011;19(7):29–35.

Martinez, F., Lopez-Arregui, E. Infection risk and intrauterine devices. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2009;88(3):246–250.

McCormack, C. The first stage of labour: physiology and early care. In Fraser D.M., Cooper M.A., eds.: Myles Textbook for Midwives, fifteenth ed, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2009.

McGrath, M. Rape Trauma Syndrome and the investigation of sexual assault. In Savino J.O., Turvey B.E., eds.: Rape Investigation Handbook, second ed, London: Academic Press, 2010.

McLoughlin, A.M.P. Unexpected birth in A&E departments. Accident and Emergency Nursing. 2001;9:242–248.

Miller, J.H., Griffin, E. Methotrexate administration for ectopic pregnancy in the Emergency Department: one hospital’s protocol/competencies. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2003;29(3):240–244.

Moulton, C., Yates, D. Obstetric, Gynaecological Genitourinary and Perinal Problems. Emergency Medicine, second ed. London: Blackwell Science Ltd.; 2004.

Munro, P.T. Management of eclampsia in the Accident and Emergency Department. Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine. 2000;17(1):7–11.

Olga, B.A., van den Akker. The psychological and social consequences of miscarriage. Expert Review of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011;6(3):295–304.

Olshansky, E. Emergency care of women who were abused was driven by the prevailing practice pattern of effective patient processing. Evidence Based Nursing. 2002;5(1):29.

Oyelese, Y., Scorza, W.E., Mastrolia, R., et al. Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstetric & Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2007;34:421–441.

Povey, D., Coleman, K., Kaiza, P., et al. Homicides, Firearm Offences and Intimate Violence 2007/08 (Supplementary Volume 2 to Crime in England and Wales 2007/08). Home Office Statistical Bulletin 02/09. London: Home Office; 2009.

Priestly, S. Emergency delivery. In Cameron P., Jelinek G., Kelly A.M., Murray L., Brown A.F.T., Heyworth J., eds.: Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine, second ed, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

Reedy, N., Brucker, M. Emergencies in gynecology and obstetrics. In Kitt S., Selfridge-Thomas J., Proehl J.A., Kaiser J., eds.: Emergency Nursing: A Physiologic and Clinical Perspective, second ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The Management of Tubal Pregnancy (Guideline 21). London: RCOG; 2004.

Sacchetti, A. Pelvic inflammatory disease. In Wolfson A.B., Hendey G.W., Ling L.J., Rosen C.L., Schaider J.J., Sharieff G.Q., eds.: Harwood-Nuss’ Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine, fifth ed., Philadelphia: Lipincott Wilkins & Williams, 2009.

Salhan, S. Dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain. In: Salhan S., ed. Textbook of Gynaecology. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, 2011.

Sanders Jordan, K. Gynecologic emergencies. In Howard P.K., Steinmann R.A., eds.: Sheehy’s Emergency Nursing: Principles and Practice, sixth ed, St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2009.

Schofield, S. Body of evidence. Emergency Nurse. 2006;13(9):9–11.

Shennon, A.H. Recent developments in obstetrics. British Medical Journal. 2003;327:604–608.

Steegers, E.A., von Dadelszen, P., Duvekot, J.J., et al. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2010;376:631–644.

Stevens, L., Kenney, A. Emergencies in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994.

Task Force on Postovulatory Method of Fertility Regulation. Randomized controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus Yupze regimen of combined oral contraceptives of emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352:428–433.

Trent, M., Bass, D., Ness, R., et al. Recurrent PID, Subsequent STI, and reproductive health outcomes: Findings from the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Study. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38(9):879–881.

Walby, S., Allen, J. Domestic Violence, Sexual Assault and Stalking: Findings from the British Crime Survey. London: Home Office; 2004.

Wechter, M.E., Wu, J., Marzano, D., et al. Management of Bartholin Duct Cysts and Abscesses: A Systematic Review. Obstetrical & Gynaecological Survey. 2009;64(6):395–404.

Williams, P.J., Broughton Pipkin, F. The genetics of pre-eclampsia and others hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Best Practice & Researach Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2011;25(4):405–417.

Winder, S., Reid, S., Condous, G. UItrasound diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Australasian Journal of Ultrasound Medicine. 2011;14(2):29–33.

Wyatt, J., Illingworth, R., Graham, C., et al. Oxford Handbook of Emergency Medicine, fourth ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.