68 Guided Lumbar Interbody Fusion

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Interbody lumbar fusion techniques have become increasingly popular because of improved rates of fusion, restoration of disc and foraminal height, and promotion of lordosis.1 Accessing the anterior column of the lumbar spine lowers the incidence of pseudoarthrosis and recreates the patient’s normal sagittal alignment.2 Late results of alleviating these effects through posterior fixation techniques alone show a significant loss of disc height at the injured segment and kyphotic deformation,3 necessitating access to the anterior column of the spine for interbody fusion. Conventional methods for accessing the anterior spine use an anterior retroperitoneal approach known as an anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF), whereby a surgeon must mobilize the great vessels, sympathetic plexus, and ureter. This approach is associated with considerable surgical trauma, and higher rates of morbidity. As a result, most of these techniques typically require the presence of an experienced general or vascular surgeon, due to the risk of serious complications.2

Gaining popularity are techniques that access the anterior lumbar spine from a lateral retroperitoneal approach with the patient positioned in a lateral decubitus position. These procedures allow access to the anterior spine with little risk of injuring the peritoneum or great vessels, reducing the surgical risks compared to a standard ALIF operation. Since 1973, similar retroperitoneal approaches were documented to access the lumbar spine for performing lumbar sympathectomies and, starting in 1997 and 1998, Rosenthal et al. and McAfee et al., respectively, reported on minimally invasive anterior retroperitoneal approaches to the spine for anterior lumbar fusion. Early results show these alternative lateral approaches to the lumbar spine to be safe and effective for anterior fusion of the first through the fifth lumbar vertebrae.2

Description of the Device

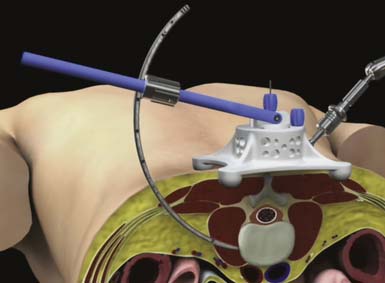

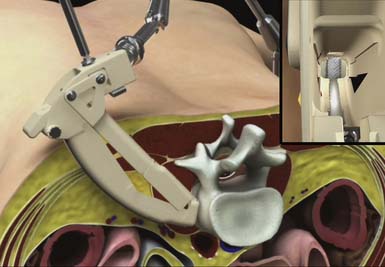

At the center of the GLIF technique is the ARC Portal System, a curvilinear lighted retractor system with a hinged top (Figure 68-1). This instrument is delivered over sequential dilators to the disc space, and the hinged top can be opened to gain direct visualization of key surgical landmarks during disc preparation. The device has proximal and distal stabilization capabilities to prevent portal migration during the procedure. In addition to the ARC Portal System, the GLIF technique utilizes specialized instrumentation to efficiently prepare the disc space for implant delivery.

Background of Scientific Testing / Clinical Outcomes

Bergey and Regan report, in a study conducted on 28 patients between 1996 and 2003, that early results show the lateral endoscopic transpsoas approach to the lumbar spine to be a safe, minimally invasive method for anterior fusion of the first through the fifth lumbar vertebrae. Their study indicates a risk of groin/thigh paresthesias and/or pain, but they report that these symptoms have proven to be transient. Of the 28 cases, eight patients experienced the transient groin/thigh numbness and/or pain; six patients experienced a small peritoneal perforation due to blunt dissection, with no bowel injuries; and two patients were converted to a mini-open lateral approach. Their report concludes that “this approach can be successfully combined with percutaneous pedicle screw fixation to provide a minimally invasive approach for circumferential fusions.”4

More recently, an extreme lateral interbody fusion technique (XLIF) has been adopted, with positive results. Pimenta indicates, in a study conducted to evaluate the XLIF technique for fixating lumbar degenerative scoliosis, that the transpsoas lateral approach has lower morbidity, does not require the use of endoscopes, avoids risks associated with anterior approaches, and avoids the invasion of the posterior spinal canal. Analyzing a consecutive series of 80 patients, Pimenta found the transpsoas approach to be a safe, reproducible, minimally invasive technique able to reconstruct sagittal balance, correct degenerative scoliosis, avoid the potential risks to the anterior approach, and promote rapid recovery.5

Wright reports similar results in a study of his first 10 patients to undergo the XLIF technique at Washington University. He reports the ability to perform a full discectomy, restore disc and foraminal height, as well as to achieve indirect canal decompression from L1 to L5. There were no vascular, visceral, or neurological complications. Nine out of ten patients ambulated on the day of surgery and were discharged on postoperative day one. One-year radiographic follow-up showed evidence of fusion. Additionally, the study indicated minimal narcotic requirement. Complications included three of 10 patients having transient pain with hip flexion that resolved by 6 weeks. His paper compared patients over 300 lb to those less than 300 lb, and found the surgical corridor to remain essentially the same length with no difference in outcomes, OR times, or blood loss. Hence, among one of the advantages of this technique he cited was that it is particularly useful in obese patients in whom anterior or posterior approaches would be more difficult.6

Operative Technique

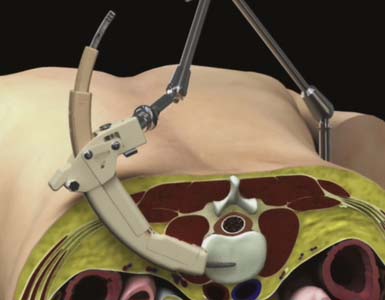

Proper patient positioning and delivery of the initial dilator are integral to the success of a GLIF technique. To facilitate proper trajectory of the instrumentation, the Calibrated Introducer was developed to repeatedly and reliably deliver the instruments to the surgical site (Figure 68-2).

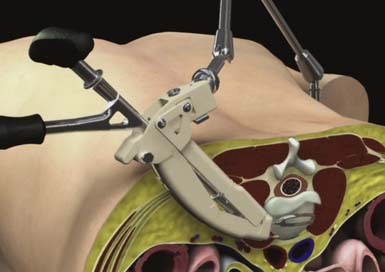

Sequential dilation is performed using Dilator 2 and Dilator 3 to retract the soft tissue through the retroperitoneal space and psoas muscle in preparation for the delivery of the access portal. The ARC Portal is delivered over Dilator 3 and gently manipulated until the instrument is fully seated against the lateral wall of the anterior spinal column (Figure 68-3). Throughout the procedure, anterior-posterior fluoroscopy is used to confirm instrument placement and trajectory. Final placement of the device is maintained using a Table Fixation Arm. An Anterior Awl that retracts from the ARC Portal is deployed into the intervertebral disc space to establish distal fixation to the spine, and the dilators are removed.

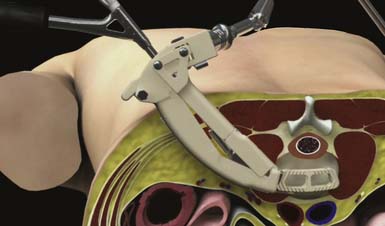

The hinged top of the ARC Portal is then opened using a toeing wrench to expose the operative site (Figure 68-4). Direct visualization is used to identify local anatomy and prepare the operative corridor for the subsequent disc-preparatory and implant insertion steps/operations. The distal perimeter of the ARC Portal can be explored using standard neuromonitoring equipment. Penfield dissectors or elevators can be used to isolate and tuck residual tissue behind the edges of the portal. Bipolar electrocautery can also be used, if necessary, to further prepare for disc visualization. A Posterior Tang, which extends into the intervertebral disc space and attaches to the ARC Portal, is assembled using the Posterior Tang Guide to complete the protected working zone within the intervertebral disc space between the Anterior Awl and Posterior Tang.

FIGURE 68-4 A retracted ARC Portal System, with inset view showing an exposed annulus view down the ARC Portal.

Specialized instrumentation is used to efficiently clean the disc space through the ARC Portal. The lateral annulus and disc nucleus are removed using an adapted annulotomy knife, annulus punch, and a series of curved pituitary rongeurs. Specialized osteotomes, Cobb elevators, curettes and rasps may be used to remove cartilaginous material from the endplates and release the contralateral annulus. Alternatively the Rotating Actuator with auxiliary Shaver Blades and Rotating Distractor attachments can be used to clear the disc space (Figure 68-5). The Shaver Blade and Rotating Distractor attachments can be used as a guide to determine an appropriate Implant Trial size used in the following step.

After the disc space has been sufficiently cleared, Implant Trials are used to determine the appropriate size of the implant with respect to height and foot print size. The GLIF system offers a range of footprint sizes: lengths, heights, and lordotic angles. Anterior-posterior fluoroscopy is used to verify placement of the Implant Trial. An implant is attached to the Impacting Inserter, and the interior channels of the implant are filled with graft material. The Impacting Inserter and implant are delivered through the ARC Portal into the disc space (Figure 68-6). Ideal implant placement is centered across the disc space, resting on both lateral edges of the disc on an anterior-posterior projection. On a lateral view, the implant should ideally be placed between the anterior third and middle of the disc space. Placement of the implant is confirmed by both anterior-posterior fluoroscopy and lateral fluoroscopy. The ARC Portal can be collapsed and all instruments are then removed.

Complications and Avoidance

Dissecting from the skin to the retroperitoneal space should be approached in a muscle-splitting approach. Mayer describes a blunt, muscle-splitting approach in which each muscular layer (external oblique, internal oblique, transverse abdominal muscles) is dissected in the direction of its fiber orientation. Care is taken to preserve the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves, which occasionally cross the surgical field at the level of L4-L5 between the layers of the internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles.7

The major drawback in a lateral retroperitoneal approach is traversing past the large psoas muscle, which covers the spine along its lateral aspect. Additionally, the psoas muscle has various nerves bordering and traversing through its confines, including the genitofemoral nerve and spinal plexus. The psoas muscle acts as a stabilizer for the lumbar spine, like guy wires stabilizing a ship’s mast, during activities such as lifting, by using compressive loading and bilateral activation.8 Thus, preserving the psoas muscle function can be related to better spinal stability and protection.

Bergey expressed concern about a 30% incidence of transient groin/thigh pain, these symptoms being consistent with the cutaneous innervation of the genitofemoral nerve. As a result, Bergey recommends staying in the anterior one third of the psoas muscle to avoid nerve root injury. Visualization and protection of the genitofemoral nerve should avoid permanent paresthesias in the anterior thigh.2 The genitofemoral nerve mainly branches from the L1 and L2 nerve root, travels through the psoas major muscle anteriorly, and descends along with the abdominal surface of the psoas major. Moro et al. report that the level where the genitofemoral nerve passes through the psoas major muscle ranges from the cranial third of the L3 vertebral body to the caudal third of the L4 vertebral body. 9 It then descends on the surface of the psoas muscle, normally under the cover of the peritoneum, and divides into the genital and femoral branches. The genital branch passes outward on the psoas major and pierces the fascia transversalis or passes through the internal abdominal ring. It then descends along the back part of the spermatic cord to the scrotum, and supplies, in the male, the cremaster muscle. In the female, it accompanies and ends in the round ligament. The femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve descends on the external iliac artery, sending a few branches to it and, after passing beneath the Poupart ligament to the thigh, supplies the skin of the anterior aspect of the thigh about midway between the pelvis and knee.2 Moro states that the risk of injuring the genitofemoral nerve increases when splitting the psoas major muscle at lower levels. However, there are reports of having succeeded in remitting the symptoms without a serious problem. 9

Moro’s anatomic study of the lumbar plexus with respect to retroperitoneal endoscopic surgery clarifies the safety zone of the psoas major muscle during retroperitoneal endoscopic surgery using cadavers. Lumbar spines were removed from embalmed cadavers, and from L1-L5, each specimen was cut in parallel with the lumbar disc space and the lumbar vertebra at the cranial third and caudal third of each lumbar vertebral body. The distribution and relationship of the lumbar plexus and nerve roots was analyzed using computer images. Moro reports, from the results of the study, that the safety zone may be at L2-L3 and above, due to the presence of the genitofemoral nerve between the cranial third of the L3 vertebral body and L4-L5. If the possibility of damaging the genitofemoral nerve is not considered, the safety zone should be at L4-L5 and above. Moro recommends starting from the abdominal edge of the vertebra when spreading the psoas major muscle at L2-L3 and below, because nerves are not located in the abdominal surface of the vertebra. Because the lumbar plexus and nerve roots were wholly contained within the psoas major muscle, one can safely split between the psoas major muscle and vertebral body to protect the nerves (retract posteriorly). Moro continues, stating that the method for retracting the psoas muscle anteriorly and reaching to the lateral surface of the vertebral body may be useful; however, according to the present study, it is the danger zone where the lumbar plexus and nerve roots are located in the center of the vertebral body and dorsally. Additionally, at the L5-S1 level, there are the L4 nerve root, L5 nerve root, femoral nerve, and obturator nerve between the psoas major muscle and the lumbar quadratus muscle. Therefore, those nerve tissues must be checked and protected with the endoscope or the alternative transperitoneal approach should be considered. 9

ADVANTAGES/DISADVANTAGES OF GLIF

Intraoperative neurologic surveillance may also provide added benefit in avoiding the exiting nerve roots, especially at L4-L5, where the L3 nerve root can cross the disc space and may be at risk if the approach is in the anterior one half of the psoas muscle.2 Peloza validates the use of an electrically elicited electromyography (EMG) monitoring system for nerve avoidance during a posterolateral approach to the spine. Electrically elicited EMG monitoring works by initiating an electrical impulse that causes nearby nerves to depolarize, which generates a muscle contraction in the corresponding myotome(s). These impulses can be detected using peripheral EMG electrodes. Peloza uses adhesive EMG surface electrodes applied to the patient’s legs, providing EMG monitoring of the myotomes associated with the spinal levels of interest: vastus medialis for L2-L4, tibialis anterior for L4-L5; biceps femoris for L5-S2; medial gastrocnemius for S1-S2. Peloza concludes that such a system could assist the spine surgeon in safely accessing the intervertebral disc space for minimally invasive lumbar interbody procedures.10

Conclusion/Discussion

The most significant complications associated with transpsoas approaches are groin/thigh pain related to disruption of the genitofemoral nerve or peritoneal perforation while establishing exposure to the spinal column and damaging the exiting nerve roots / lumbar plexus. However, symptoms related to interference of the genitofemoral nerve seem to be transient and are reported to remit in 6 weeks. As with any surgical procedure there should be a “bailout” plan; in this case it would be to convert to mini-open in the case of encountering scar tissue from previous surgeries or any other unforeseen complication. These less conventional lateral approaches to the spine have a steep learning curve and hands-on training in a laboratory is recommended.

1. Steinmetz M.P., Resnick D.K. Use of a ventral cervical retractor system for minimal access transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: technical case report. Operative Neurosurgery. 2007;60(2):E175-E176.

2. Bergey D.L., Villavicencio A.T., Goldstein T., Regan J.J. Endoscopic lateral transpsoas approach to the lumbar spine. Spine. 2004;29(15):1681-1688.

3. Olinger A., Hildebrandt U., Mutschler W., Menger M.D. First clinical experience with an endoscopic retroperitoneal approach for anterior fusion of lumbar spine fractures from levels T12 to L5. Surg. Endosc.. 1999;13:1215-1219.

4. Bergey D., Regan J. Lateral endoscopic transpsoas spinal fusion: review of technique and clinical outcomes in a consecutive series. Spine J. 2003;3(5):S166.

5. Pimenta L., Diaz R., Phillips F., Bellera F., Vigna F. M. Da Silva, XLIF: 90 degrees, minimally invasive surgical technique to treatment lumbar degenerative scoliosis in adults: clinical and radiological results in a 15 months follow-up study. Rio Janeiro, Brazil: Minimally Invasive and Reconstructive Spine Department at Santa Rita Hospital World Spine III Interdisciplinay Congress in Spine Care Meeting; 2005.

6. N.M. Wright, XLIF: the first 10 patients at Washington University, Washington University School of Medicine. St. Louis, Missouri World Spine III, Rio de Jinero, Brazil, (Sep 2005).

7. Mayer M.H. A new microsurgical technique for minmally invasive anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine. 1997;22(6):691-699.

8. Santaguida P.L., McGill S.M. The psoas major muscle: a three dimensional geometric study. J. Biomech. 1995;28(3):339-345.

9. Moro T., Kikuchi S.I., Konno S.I., Yaginuma H. An anatomic study of the lumbar plexus with respect to retroperitoneal endoscopic surgery. Spine. 2003;28(5):423-428.

10. Peloza J. Validation of neurophysiological monitoring of posterolateral approach to the spine via discogram procedure, 9th International Meeting on Advanced Spine Techniques. Dallas, Texas: Center for Spine Care; 2002.