Growth hormone-secreting pituitary tumors

1. What is the normal function of growth hormone in children and adults?

In children, growth hormone (GH) is responsible for linear growth. In children and adults, GH has many effects on intermediary metabolism, including protein synthesis and nitrogen balance, carbohydrate metabolism, lipolysis, and calcium homeostasis.

2. How are levels of GH normally regulated?

Pituitary secretion of GH is regulated primarily by two hypothalamic hormones: stimulatory GH-releasing hormone (GH-RH) and inhibitory somatostatin. Secretion of GH is also affected by adrenergic and dopaminergic hormones as well as by other central nervous system and peripheral factors.

3. Does GH directly affect peripheral tissues?

No. Most (although not all) effects of GH are mediated by another hormone called insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). IGF-1 is made by the liver and other organs in response to stimulation by GH. IGF-1 feeds back to the pituitary gland and suppresses GH secretion. Unlike GH, IGF-1 has a long half-life in plasma; thus plasma IGF-1 levels are helpful in the diagnosis of GH abnormalities.

4. What are the clinical features of excessive production of GH in children?

In children who have not yet undergone puberty and whose long bones still respond to GH, excessive GH causes accelerated linear growth. The result is gigantism.

5. Describe the clinical features of excessive production of GH in adults.

In adults, excessive GH causes acromegaly. Acromegaly is rare, with an incidence of approximately 5 cases per million people per year, and often progresses gradually and insidiously. The pathologic and metabolic effects of acromegaly are summarized in Table 21-1.

TABLE 21-1.

CLINICAL EFFECTS OF ACROMEGALY

| CLINICAL EFFECT | CAUSE |

| Coarse features | Periosteal formation of new bone |

| Enlarged hands and feet | Soft tissue hypertrophy |

| Excess sweating | Hypertrophy of sweat glands |

| Deepened voice | Hypertrophy of larynx |

| Skin tags | Hypertrophy of skin |

| Upper airway obstruction and sleep apnea | Hypertrophy of tongue and upper airway |

| Osteoarthritis | Hypertrophy of joint cartilage and osseous overgrowth |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Hypertrophy of joint cartilage and osseous overgrowth |

| Hypertension, congestive heart failure | Cardiac hypertrophy |

| Hypogonadism | Multifactorial |

| Diabetes mellitus, glucose intolerance | Insulin antagonism, other factors |

| Colonic polyps | Colonic hypertrophy |

6. What is the single best clue in examining a patient suspected of having acromegaly?

An old driver’s license picture or other old photographs provide the best clues. Patients with acromegaly are often unaware of the gradual disfigurement due to the disease or attribute it to aging. Comparing serial photographs can help establish the diagnosis as well as date its onset.

7. From what do patients with acromegaly die?

Acromegaly increases cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, including hypertension, glucose intolerance, cardiomyopathy, and sleep apnea. The mortality from inadequately treated acromegaly is about double the expected rate in healthy age-matched subjects. Major causes of death are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and diabetes. Improved treatment has decreased this risk, but there is still a 30% higher risk of mortality in patients with acromegaly.

8. The husband of a patient with acromegaly complains that he cannot sleep because his wife snores. Is this relevant?

Sleep apnea occurs in 50% to 70% of patients with acromegaly. It can be due to soft tissue overgrowth of the upper airway or to altered central respiratory control. Sleep apnea may contribute to morbidity and mortality in acromegaly by producing hypoxia and pulmonary hypertension.

9. If I suspect that a patient may have acromegaly, what test should I order?

The single best screening test for acromegaly is measurement of the plasma level of IGF-1. Unlike those for GH levels, which are pulsatile and higher at night, blood specimens for IGF-1 measurement can be drawn any time of day. In adults, acromegaly is essentially the only condition that causes elevated IGF-1 values. In children, IGF-1 levels are more difficult to interpret because IGF-1 is normally high in growing children. IGF-1 levels may be less accurate in mild acromegaly, malnutrition, or hepatic or renal disease.

10. The patient’s IGF-1 value is not elevated, but I still think that she may have acromegaly. What other test should I order?

The gold standard test to rule out acromegaly is the measurement of serum GH levels in the fasting state and after glucose suppression. Healthy subjects suppress GH levels to less than 1 ng/mL 2 hours after an oral glucose load (75 g), whereas patients with acromegaly show insufficient suppression of GH levels. This test may be unreliable in patients with diabetes mellitus, hepatic or renal disease, obesity, or pregnancy, or in patients undergoing estrogen therapy.

11. After the biochemical diagnosis of acromegaly or gigantism is made, what is the next step?

Excessive secretion of GH is almost always due to a benign pituitary tumor. Therefore the next step is to obtain a radiologic study of the pituitary gland. The optimal study is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with special cuts through the pituitary gland.

12. What causes GH-secreting pituitary tumors?

GH-secreting pituitary tumors are monoclonal, indicating that a spontaneous somatic mutation is a key event in neoplastic transformation of somatotrophs. Further studies have clarified the nature of the mutation in some GH tumors that appear to have an altered stimulatory subunit (GS) of the G-proteins that regulate adenylate cyclase activity. In a mutated cell, alterations in the GS subunit cause autonomous adenylate cyclase activity, somatotroph proliferation, and elevated GH secretion. However, the mutant GS is found in only about 40% of patients with acromegaly. The mechanisms of GH regulation and tumor growth differ in other patients with acromegaly.

13. Are other endocrine syndromes possible in patients with acromegaly or gigantism?

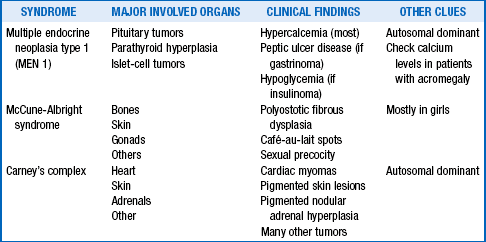

Yes. Otherwise acromegaly and gigantism would not be endocrine disorders. Three endocrine syndromes include acromegaly (Table 21-2).

14. Do other tumors besides pituitary tumors make GH and cause acromegaly or gigantism?

15. Do tumors ever cause acromegaly or gigantism by making excessive GH-RH?

Yes. Rare cases of GH-RH production by various tumors have been described in the lung, gastrointestinal tract, and adrenal glands. They cause acromegaly by stimulating pituitary secretion of GH. The clinical and biochemical features of acromegaly are indistinguishable from those of acromegaly due to a pituitary adenoma. Pituitary enlargement also occurs as a result of hyperplasia of somatotrophs. Some patients have undergone transsphenoidal surgery before the correct diagnosis was made. Therefore the plasma level of GH-RH should be measured in any acromegalic patient with an extrapituitary abnormality or in whom hyperplasia is shown by pituitary pathology.

16. If MRI of the pituitary confirms a tumor in the acromegalic patient, what issues other than the metabolic effects of excessive GH should be considered?

1. Is the tumor making any other pituitary hormones besides GH? For example, many GH-secreting tumors also produce prolactin; rare tumors also make thyroid-stimulating hormone or other pituitary hormones. In patients with acromegaly, prolactin levels should be measured, as well as other hormones when clinically indicated.

2. Is the tumor interfering with the normal function of the pituitary gland? Specifically, how are the patient’s thyroid, adrenals, and gonads functioning? Does the patient have diabetes insipidus? It is important to diagnose and treat pituitary insufficiency before therapy for the excessive secretion of GH, especially if the patient is scheduled for surgery.

3. Is the tumor causing effects owing to its size and location? Possible effects include headache, visual field disturbances, and extraocular movement abnormalities. Formal visual field examination should be carried out in patients with large pituitary tumors.

18. How should acromegaly or gigantism be treated?

Goals of therapy for GH-secreting tumors include mortality reduction, tumor shrinkage, and control of GH hypersecretion. The treatment of choice for GH-secreting tumors is transsphenoidal surgery by an experienced pituitary surgeon. Most patients with microadenomas are cured by such a procedure, and larger tumors are debulked. When it is performed by experienced hands, surgical complications are unusual. Significant reduction in GH levels and improvement in symptoms typically follow surgery, even when further treatment is required. Certain patients may benefit from medical therapy before surgery to reduce surgical risks, including those with congestive heart failure, severe sleep apnea, intubation problems, or other comorbidites of acromegaly. There are no conclusive data that presurgical treatment improves cure rates, however.

19. What are the options for medical therapy of acromegaly?

Approximately 40% to 60% of GH macroadenomas are not controlled by surgery alone, and adjuvant therapy is indicated. Three drug classes are available for the treatment of acromegaly: somatostatin analogs (octreotide and lanreotide), the GH receptor antagonist pegvisomant, and dopamine agonists. Dopamine agonists are not discussed further here, because their efficacy is limited.

20. Discuss the mechanism of action of somatostatin analogs.

Most GH-secreting tumors have somatostatin receptors and respond to exogenous somatostatin with decreases in GH levels. The development of long-acting forms of octreotide, an analog of somatostatin, was a major advance in the treatment of acromegaly.

21. How effective are somatostatin analogs?

Somatostatin analogs markedly decrease GH levels in most acromegalic patients, with amelioration of many of the symptoms and side effects of acromegaly. Up to 70% of patients receiving somatostatin analogs achieve biochemical remission. Significant tumor shrinkage occurs in approximately 70% of patients. However, these agents do not cure acromegaly; stopping the drugs usually leads to increases in GH levels and tumor regrowth. Somatostatin analogs are commonly used indefinitely after surgery has failed to achieve biochemical control of GH hypersecretion. They can also be used before surgery to improve comorbidities, temporarily after surgery during the wait for radiation therapy to take effect (see later), or instead of surgery in carefully selected patients. Common side effects include gastrointestinal symptoms and gallstone formation.

22. Describe the mechanism of action of pegvisomant.

Pegvisomant blocks GH action at peripheral GH receptors, thereby improving IGF-1 levels, reducing clinical GH effects, and correcting metabolic defects. It does not appear to affect tumor size in the great majority of patients, but tumor size should be monitored, given the drug’s mechanism of action. It is usually used for patients whose disease is resistant to or who do not tolerate somatostatin analogs, or in combination with somatostatin analogs to improve biochemical control. The main side effect of pegvisomant is liver function abnormalities, which are usually transient. Note that GH levels cannot be monitored in patients taking pegvisomant.

23. What about radiation therapy for acromegaly?

Conventional radiation therapy of GH-secreting tumors causes a gradual decline in GH levels over many years, with maximal effect occurring at 10 to 15 years. Therefore, it is generally reserved as a third-line therapy for acromegaly. It may also increase long-term mortality. Stereotactic radiotherapy, which consists of applying a highly concentrated high-energy radiation therapy beam to the tumor, may be more effective and work more quickly than conventional radiation therapy for pituitary tumors. However, stereotactic radiotherapy still takes months to years to work. If radiation therapy is deemed necessary in acromegaly, the choice of a conventional or stereotactic approach depends on the residual tumor size and location. Hypopituitarism eventually develops in many patients from radiation therapy, and there may also be small risks of vision deficits, secondary tumors, cerebrovascular events, and cognitive effects.

24. How can one tell whether a patient has been cured of acromegaly?

Older studies defined cure as a randomly measured GH level below 5 ng/mL. Later studies have shown that this criterion is inadequate, and more rigorous criteria have been developed as GH assays have become more sensitive. For complete control of GH secretion, patients should have normal age-adjusted IGF-1 and basal GH levels, and GH levels less than 0.4 ng/mL following an oral glucose load.

25. The patient has undergone transsphenoidal surgery for acromegaly and now has normal IGF-1 and GH levels and suppressed levels of GH following an oral glucose load. How should this patient be monitored?

It appears that the patient is cured, but GH tumors can slowly regrow over years. At the least, measurements of GH and IGF-1 should be repeated every 6 to 12 months. Some physicians measure GH levels following glucose administration as well. Tumor mass should be monitored at intervals with pituitary MRI. The patient also needs an evaluation for colonic neoplasia, because some studies suggest that the incidence of premalignant colonic lesions may be increased in acromegaly. In addition, one must assess whether the surgery damaged normal pituitary function by determining the patient’s thyroid, adrenal, gonadal, and posterior pituitary function. The effects of surgery on visual fields should be assessed, especially if the patient had preoperative defects.

26. The patient asks which symptoms and physical abnormalities will improve after cure is confirmed. What is the appropriate answer?

Most soft tissue changes improve, including coarsening of facial features, increased size of hands and feet, upper airway hypertrophy, carpal tunnel syndrome, osteoarthritis, and excessive sweating. Unfortunately, bony overgrowth of the facial bones does not regress after treatment. Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes also improve. However, not all comorbidities resolve with successful treatment of GH hypersecretion, and hypertension, cardiac dysfunction, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and sleep apnea may require additional management.

27. For bonus points, name an actor with acromegaly and the movie in which he starred.

Giustina, A, Chanson, P, Bronstein, MD, et al. A consensus on criteria for cure of acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3141–3148.

Katznelson, L. Approach to the patient with persistent acromegaly after pituitary surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4114–4123.

Melmed, S. Acromegaly pathogenesis and treatment. J Clin Investigation. 2009;119:3189–3202.

Melmed, S, Colao, A, Barkan, A, et al, Guidelines for acromegaly management. an update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:1509–1517.

Sherlock, M, Woods, C, Sheppard, MC. Medical therapy in acromegaly. Nat Rew Endocrinol. 2011;7:291–300.