Chapter 177 Group B Streptococcus

Epidemiology

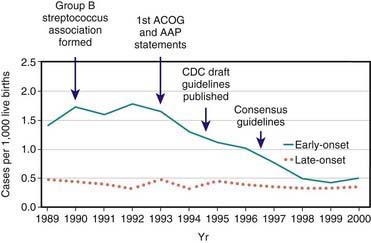

GBS emerged as a prominent neonatal pathogen in the late 1960s. For the next 2 decades, the incidence of neonatal GBS disease remained fairly constant, affecting 1.0-5.4/1,000 liveborn infants in the USA. Two patterns of disease were seen: early-onset disease, which presents at <7 days of age, and late-onset disease, which presents at 7 days of age or later. In the 1990s, widespread implementation of maternal chemoprophylaxis led to a striking 65% decrease in the incidence of early-onset neonatal GBS disease in the USA, from 1.7/1,000 live births to 0.6/1,000 live births, whereas the incidence of late-onset disease remained essentially stable at approximately 0.4/1,000 (Fig. 177-1). Release of revised guidelines in 2002 coincided with a further reduction in the incidence of early-onset neonatal disease. In other developed countries, rates of neonatal GBS disease are similar to those in the USA prior to use of GBS chemoprophylaxis. In the developing world, GBS is not a major cause of neonatal sepsis, even though the prevalence of maternal vaginal colonization with GBS (a major risk factor for neonatal disease) among women from developing countries is similar to that reported among women living in the USA. The incidence of neonatal GBS disease is higher in premature and low birthweight infants, although most cases occur in full-term infants.

Clinical Manifestations

Two syndromes of neonatal GBS disease are distinguishable on the basis of age at presentation, epidemiologic characteristics, and clinical features (Table 177-1). Early-onset neonatal GBS disease presents within the 1st 6 days of life and is often associated with maternal obstetric complications, including chorioamnionitis, prolonged rupture of membranes, and premature labor. Infants may appear ill at the time of delivery, and most infants become ill within the 1st 24 hr of birth. In utero infection may result in septic abortion. The most common manifestations of early-onset GBS disease are sepsis (50%), pneumonia (30%), and meningitis (15%). Asymptomatic bacteremia is uncommon but can occur. In symptomatic patients, nonspecific signs such as hypothermia or fever, irritability, lethargy, apnea, and bradycardia may be present. Respiratory signs are prominent regardless of the presence of pneumonia and include cyanosis, apnea, tachypnea, grunting, flaring, and retractions. A fulminant course with hemodynamic abnormalities, including tachycardia, acidosis, and shock, may ensue. Persistent fetal circulation may develop. Clinically and radiographically, pneumonia associated with early-onset GBS disease is difficult to distinguish from respiratory distress syndrome. Patients with meningitis often present with nonspecific findings, as described for sepsis or pneumonia, with more specific signs of central nervous system (CNS) involvement initially being absent.

Table 177-1 CHARACTERISTICS OF EARLY- AND LATE-ONSET GBS DISEASE

| EARLY-ONSET DISEASE | LATE-ONSET DISEASE | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at onset | 0-6 days | 7-90 days |

| Increased risk after obstetric complications | Yes | No |

| Common clinical manifestations | Sepsis, pneumonia, meningitis | Bacteremia, meningitis, other focal infections |

| Common serotypes | Ia, III, V, II, Ib | III predominates |

| Case fatality rate | 4.7% | 2.8% |

Adapted from Schrag SJ, Zywicki S, Farley MM, et al: Group B streptococcal disease in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, N Engl J Med 342:15–20, 2000.

Treatment

Penicillin G is the treatment of choice of confirmed GBS infection. Initial empirical therapy of neonatal sepsis should include ampicillin and an aminoglycoside (or cefotaxime), both for the need for broad coverage pending organism identification and for synergistic bactericidal activity. Once GBS has been definitively identified and a good clinical response has occurred, therapy may be completed with penicillin alone. Especially in cases of meningitis, high doses of penicillin (450,000-500,000 U/kg/day) or ampicillin (300 mg/kg/day) are recommended because of the relatively high mean inhibitory concentration of penicillin for GBS as well as the potential for a high initial CSF inoculum. The duration of therapy varies according to the site of infection (Table 177-2) and should be guided by clinical circumstances. Extremely ill near-term patients with respiratory failure have been successfully treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 177-2 RECOMMENDED DURATION OF THERAPY FOR MANIFESTATIONS OF GBS DISEASE

| TREATMENT | DURATION |

|---|---|

| Bacteremia without a focus | 10 days |

| Meningitis | 2-3 wk |

| Ventriculitis | 4 wk |

| Osteomyelitis | 4 wk |

Adapted from the American Academy of Pediatrics: Group B streptococcal infections. In Pickering LK, editor: Red book: 2000 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 25, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2000, American Academy of Pediatrics, pp 537–544.

Prevention

Chemoprophylaxis

Administration of antibiotics to pregnant women before the onset of labor does not reliably eradicate maternal GBS colonization and is not an effective means of preventing neonatal GBS disease. Interruption of neonatal colonization is achievable through administration of antibiotics to the mother during labor (Chapter 103). Infants born to GBS-colonized women with premature labor or prolonged rupture of membranes who were given intrapartum chemoprophylaxis had a substantially lower rate of GBS colonization (9% vs 51%) and early-onset disease (0% vs 6%) than did the infants born to women who were not treated. Maternal postpartum febrile illness was also decreased in the treatment group.

In the mid-1990s, guidelines for chemoprophylaxis were issued that specified administration of intrapartum antibiotics to women identified as high-risk by either culture-based or risk factor–based criteria. These guidelines were revised in 2002 after epidemiologic data indicated the superior protective effect of the culture-based approach in the prevention of neonatal GBS disease (Chapter 103). According to current recommendations, vaginorectal GBS screening cultures should be performed for all pregnant women at 35-37 wk gestation. Any woman with a positive prenatal screening culture, GBS bacteriuria during pregnancy, or a previous infant with invasive GBS disease should receive intrapartum antibiotics. Women whose culture status is unknown (culture not done, incomplete, or results unknown) and who deliver prematurely (<37 wk gestation) or experience prolonged rupture of membranes (≥18 hr) or intrapartum fever (≥38.0°C) should also receive intrapartum chemoprophylaxis. If amnionitis is suspected, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy that includes an agent active against GBS should replace GBS prophylaxis. Routine intrapartum prophylaxis is not recommended for women with GBS colonization undergoing planned cesarean delivery who have not begun labor or had rupture of membranes.

These guidelines also suggest an approach for the management of infants born to mothers who received intrapartum chemoprophylaxis (Chapter 103). Data from a large epidemiologic study indicate that the administration of maternal intrapartum antibiotics does not change the clinical spectrum or delay the onset of clinical signs in infants who developed GBS disease despite maternal prophylaxis. Thus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines reserve a full diagnostic evaluation for those infants who appear clinically ill or whose mothers are suspected of having chorioamnionitis.

Baker CJ, Kasper DL. Correlation of maternal antibody deficiency with susceptibility to neonatal group B streptococcal infection. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:753-756.

Baker CJ, Rench MA, McInnes P. Immunization of pregnant women with group B streptococcal type III capsular polysaccharide-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine. Vaccine. 2003;21:3468-3472.

Boyer KM, Gotoff SP. Prevention of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease with selective intrapartum chemoprophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1665-1669.

Bromberger P, Lawrence JM, Braun D, et al. The influence of intrapartum antibiotics on the clinical spectrum of early-onset group B streptococcal infection in term infants. Pediatrics. 2000;106:244-250.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early-onset group B streptococcal disease—United States, 1998–1999. MMWR. 2000;49:793-796.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: a public health perspective. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1996;45(RR-7):1-24.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. Revised guidelines from CDC. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-11):1-22.

Fernandez M, Rench MA, Albanyan EA, et al. Failure of rifampin to eradicate group B streptococcal colonization in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:371-376.

Lin F-Y, Azimi P, Weisman LE, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles for group B streptococci isolated from neonates, 1995–1998. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:76-79.

Moore MR, Schrag SJ, Schuchat A. Effects of intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis for prevention of group-B-streptococcal disease on the incidence and ecology of early-onset neonatal sepsis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:201-213.

Natarajan G, Johnson YR, Zhang F, et al. Real-time polymerase chain reaction for the rapid detection of group B streptococcal colonization in neonates. Pediatrics. 2006;118:14-22.

Phares CR, Lynfield R, Farley MM, et al. Epidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1999–2005. JAMA. 2008;299(17):2056-2065.

Puopolo KM, Eichenwald EC, Madoff LC. Early-onset group B streptococcal disease in the era of maternal screening. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1240-1246.

Schrag SJ, Zywicki S, Farley MM, et al. Group B streptococcal disease in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:15-20.

Schuchat A. Group B streptococcal disease: from trials and tribulations to triumph and trepidation. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:751-756.

Skoff TH, Farley MM, Petit S, et al. Increasing burden of invasive group B streptococcal disease in nonpregnant adults, 1990–2007. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:85-92.

Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, et al. Changes in pathogens causing early-onset sepsis in very-low-birthweight infants. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:240-247.

Stoll BJ, Schuchat A. Maternal carriage of group B streptococci in developing countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:499-503.

VanDyke MK, Phares CR, Lynfield R, et al. Evaluation of universal antenatal screening for group B streptococcus. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2626-2636.

Yow MD, Mason EO, Leeds LJ, et al. Ampicillin prevents intrapartum transmission of group B streptococcus. JAMA. 1979;241:1245-1247.

Zaleznik DF, Rench MA, Hillier S, et al. Invasive disease due to group B streptococcus in pregnant women and neonates from diverse population groups. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:276-281.